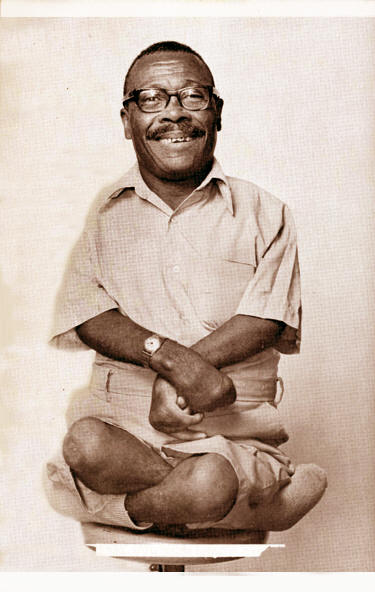

SOLD. “The Human Cigarette Factory” Carte de Visite

Authentic Coney Island Carte de Visite / Printed Photograph of “The Human Cigarette Factory”, These cards were sold by the subject in the photo, as a means to make a living, when so called ‘Freak Shows’ still existed on Coney Island, USA. Measures 4 x 6 inches.

$100.

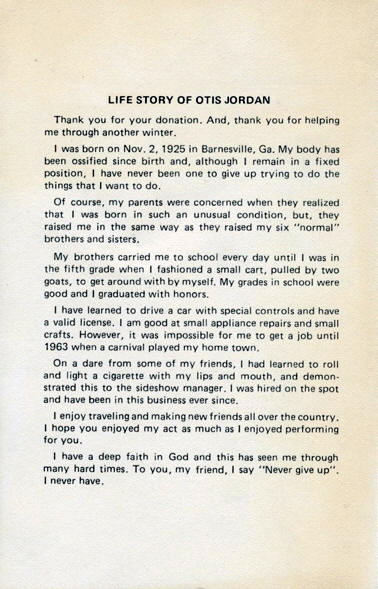

Born in Barnesville, Georgia, on November 2, 1926, Otis Jordan was halfway between a human torso and an ossified man. He suffered from arthrogryposis multiplex congenita (AMC), a rare birth defect which causes permanent flexion of the joints. This deformity of his arms and legs left young Otis more or less helpless – at least physically. What he lacked in mobility he made up for in brains, and from an early age he understood the importance of getting an education. One of his six normal siblings was charged with carrying the handicapped boy to and from school each day. When he was in the fifth grade, however, Otis sought to alleviate this burden on his family by devising his own means of transportation. He designed a cart to be pulled by the family goat. From day one Otis’ parents were supportive of their disabled son and taught him never to give up on doing the things he wanted to do. With his father’s help, Otis was able to realize his goat cart design within a month. He finished school with honors and later obtained a degree by correspondence.

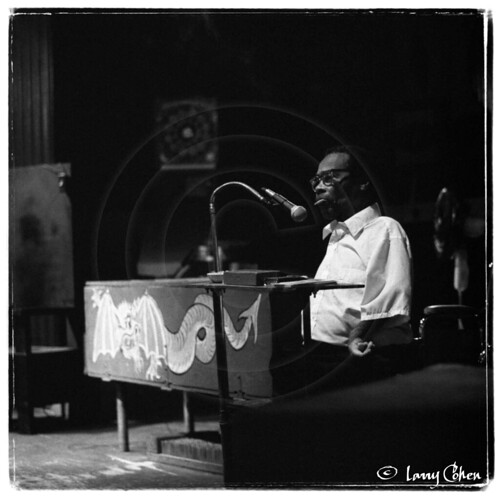

Though no longer dependent on others to get around, Otis was still unable to make a living on his own. He tried selling pencils, and later newspapers, from his goat cart, but neither of these businesses generated enough income. Then, in 1963, when Otis and a friend went to the freak show at a local fair, Otis decided to pay a visit to showman Dick Burnett. He had become quite prolific at using his mouth and two normal fingers to perform tasks, eventually becoming a skilled appliance repairman. But it was his ability to roll and light a cigarette using only his mouth that sold Burnett on Otis as a performer.

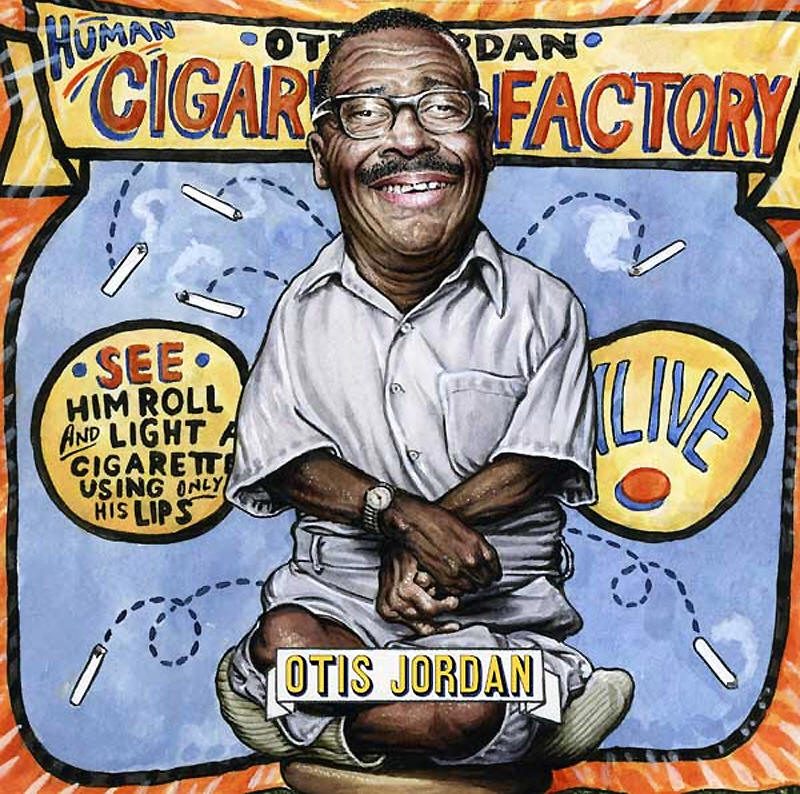

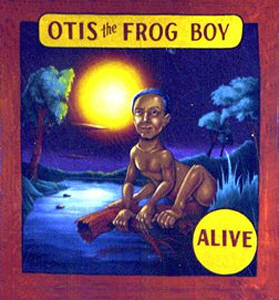

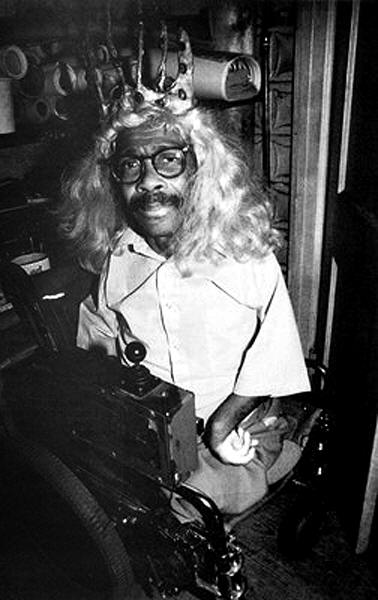

Otis was nicknamed The Frog Boy because of his permanently-bent legs. At first, Otis was uncomfortable being the center of attention. He sat in complete silence, performing his cigarette-rolling act for curious audiences. However, Otis soon proved himself a natural showman, giving his own inside lectures. Footage from Ward Hall’s 1991 documentary My Very Unusual Friends shows just how skillful the Frog Boy was at playing the crowd – he was not just a cigarette roller but a sort of fire-eater as well, partially swallowing and then retrieving his cigarette.

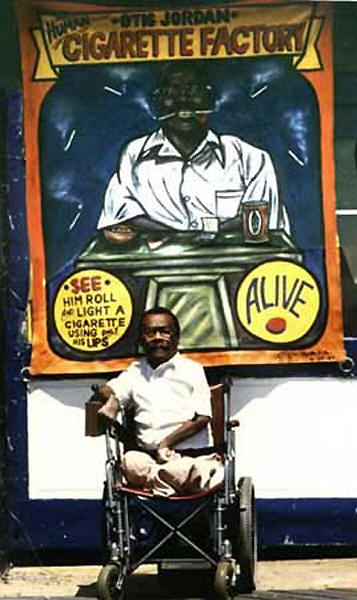

Otis’ success as The Frog Boy would continue until 1984, when politically-correct backlash nearly left him without a job. A woman named Barbara Baskin – Bogdan says she was handicapped herself – saw Otis with Whitey Sutton’s sideshow at the New York State Fair, and was horrified. She went to court to get the sideshow banned from the fair. Otis fought back, vehemently defending his right to work – and won. In 1985 he travelled to Alton, Illinois, to speak in favor of a proposed statue of Alton’s most famous resident, Robert Wadlow, the tallest man who ever lived. The statue was erected despite a storm of protests from the politically-correct faction, who did not want the nine-foot-tall man categorized as a “freak”. In 1987, when Otis Jordan joined the Coney Island sideshow, he was re-named the Human Cigarette Factory, and there he spent three years delighting audiences with his dextrous mouth and amiable personality. In 1990, while visiting family in Georgia, he died from kidney disease.

“I can’t understand it. How can she say I’m being taken advantage of? Hell, what does she want for me – to be on welfare?” – Otis Jordan on Barbara Baskin, 1984 (Bogdan)

Text Elizabeth Anderson – The Phreeque Show

http://www.sideshowworld.com/76-Blow/Otis/Jordan.html

http://www.oddee.com/item_98922.aspx

https://travsd.wordpress.com/tag/human-cigarette-factory/

The stock “lecture” on Otis refereed to his condition as “arrested development.” Although this term probably leaves a lot to be desired from a clinical standpoint, I’ll let it stand. Actually, Otis’ physical was the result of several things but, unless you own a dictionary of medical jargon (and understand it), “arrested development” will do just fine. The only part of Otis’ body that would pass normal was his head. The rest of him was, as previously mentioned about like a four year old child in size. A paralyzed four year old with the exception of the thumb and index finger of his right hand. Everything above his shoulders worked and his internal organs functioned properly. He had developed the ability to propel his body in whatever direction he desired by using his neck muscles, thereby throwing his shoulders and the frozen anatomy below them from side to side. This took a great deal of effort but he would wobble himself pretty well in this manner.

In a career that spanned over twenty-five years, Otis appeared with a host of sideshows owned by such operators as Elsie Sutton, Jeff Murray, Dean Potter, Ward Hall and myself. Each one of them has their own “Otis” stories to tell, some funny, some poignant but all with reverence for the fact their lives had been touched by a very unique human being.

I, of course, have a funny story regarding Mr. Jordan.

In his earlier sideshow days, Otis was always “lectured on.” The inside lecturer (emcee for the sideshow vernacular impaired), would introduce Otis, tell you why he was called “The Frog Boy,” (in case your imagination wasn’t up to making the quantum leap to make this observation for yourself) and then do a quasi-medical explanation of his condition. Some of these “lectures” were pretty brutal, particularly when the lecturer mangled medical terms, or worse yet, invented new ones. When I first knew Otis, the magician was also the lecturer. To be as charitable as possible, he was a good magician. Each day, I endured his Walter Brennan-style delivery of, “Little Otis was born in a small town in Georgia of normal parents.” I often wondered how many people went home and tried to locate Normal Parents in their Rand McNally.

At any rate, the lecture would wind up with brief question and answer period.

“How old are you Otis?'”

“Thirty-two.”

“How tall are you?”

“Twenty-seven inches.”

After this exhilarating exchange the lecturer would pitch Otis’ miniature bibles for fifty cents, the proceeds of which, ostensibly, did everything from starving off off-season hunger pangs to building a national research center to cure frogboyitis.

There were human oddities on the circuit that did their own lecture, doubtless inspired into doing so to salvage whatever dignity they could after being subjected to the forgoing repartee.

Otis was terribly “mike shy.” When I began doing this lecture I tried to expand on the little “man-on-the-street”, segment by tossing in questions that required more than a monosyllabic answer. I’d either get a terrified look or an inaudible grunt in return. It appeared that the audio portion of the Otis Jordan show was always going to remain at “thirty-two” and “twenty-seven” inches.

Then came a sweltering hot night in New Britain, Connecticut. It was Otis’ first year of employment with me and I’d managed to buy him a nice little trailer that had everything except an air conditioner. We closed the show at around midnight and it was still about 85 degrees. I’d just finished dropping the banners and walked back into the tent, prepared to carry Otis to his trailer.

“Gonna be awful hot in there tonight,” Otis said. “Think maybe I’d rather sleep out here,” adding, “got my gun, I’ll be all right.”

It was a rubble-strewn urban lot and we’d already had problems with neighborhood gangs. I knew Otis could handle his Pirates of Penzance-looking gun pretty well, but I was uneasy about leaving him alone in the tent. He was, however, not about to give up the idea of “camping out.” Reluctantly, I trudged off to my own humid trailer.

My wife and I had almost fallen asleep when she nudged me awaked with a hushed, “Did you hear that?”

Whatever “that” was, I didn’t hear it.

“Shh-,” she whispered, “listen.”

It was kind of electronic buzzy sound interspersed with a faint voice.

“Somebody’s tv.,” I said.

“Light plant’s off,” she countered.

“Somebody’s battery tv.”

“Get up and check,” she said ignoring my comedic efforts.

I opened the trailer door and listened. The sound was coming from inside the tent. Drawing myself up to my not particularly imposing five foot eight inches, I lifted the sidewall, expecting to find Otis holding a group of things at bay with his comic opera pistol.

“-chickens,” an unexpectedly melodious baritone voice was singing. “Ain’t nobody here but us chickens.”

Oblivious to my sidewall entrance, Otis continued to croon into the mike. “Ain’t nobody here but us chickens.”

“A star is born!” I announced from the shadows.

“Didn’t think you could hear me,” said Mr. Jordan with a kid-with-his-hand-in-the-cookie-jar grin.

The next day Otis began lecturing on himself.

Otis’ final years of sideshow performing were spent in Coney Island in the employ of John Bradshaw and Dick Zigun.

Here Otis appeared as the “Human Cigarette Factory” rather than “The Frog Boy.” The age of political correctness was now, upon us. Other than the new title, nothing changed in his presentation.

Many physically handicapped sideshow acts performed some feat or another to illustrate how they’d overcome their particular disability. Armless people would, for example, draw, typewrite, or knit using their feet. In Otis’ case he’d roll and light a cigarette and then puff smoke rings and make it disappear and appear-“sleight of mouth as I referred to it. Hence the new “Human Cigarette Factory” title.

Ironically, if Otis was still alive today he’d be out of business with that title, as cigarette smoking has been added to freak gawking by the tongue-clucking set.

A new title for Otis? Well, I’d probably lock horns with the legal folks at Reader’s Digest, but my vote would have to go to, “The Most Unforgettable Person I’ve Ever Met.” It’d be the most factual title I ever painted on a banner.

from James Taylor’s – Shocked and Amazed