Esquire UK Feature Aids Memorial 2021

The Instagram Account That Remembers the Human Story, and the Human Cost, of the HIV Crisis

As Pride month comes to a close, those who aren’t here to celebrate live on – and have their lives celebrated – in The Aids Memorial

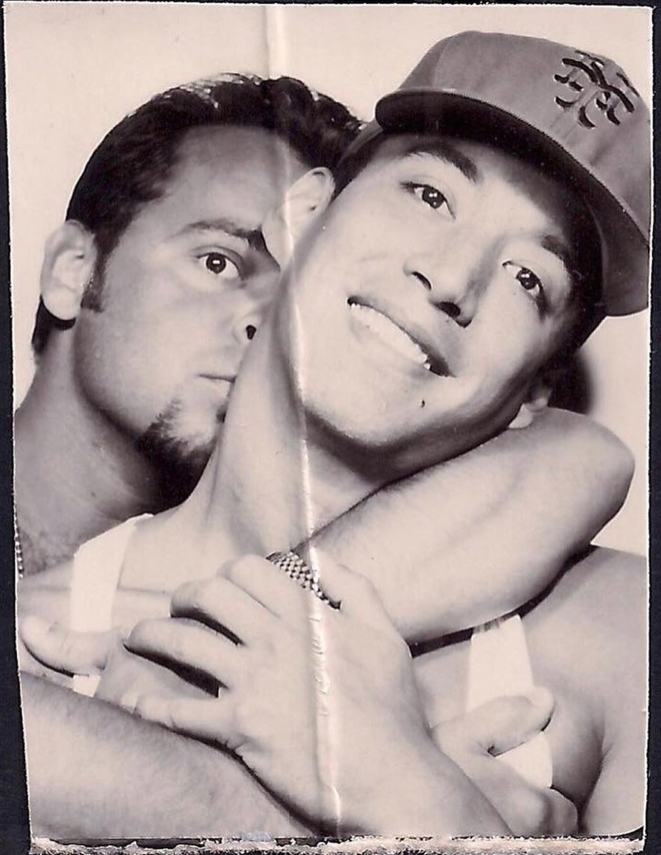

“Raphael Aninat was born in Chile and he came to New York to find fortune and fame as an interior designer. We met at a party I gave when I was living in Chelsea and we became instant best friends. We navigated the perilous shoals of love, sex and parties in the early days of Aids. I survived, Raphael didn’t.”

This sort of firsthand account is commonplace within The Aids Memorial: a digital mausoleum in which the forgotten stories and photographs of Aids patients are retold, largely by surviving friends and relatives.

But this sort of firsthand account is unusual everywhere else. For while Hollywood and the mainstream culture has increasingly (and rightly) come to shed a bigger light on the Aids crisis in the last decade, so rarely do we hear and see these stories in such an undiluted way. Screenwriters have had no hand in dramatising these anecdotes. We, the readers, don’t have to pry fact from fiction. When we’re presented with a faded, sun-dappled photograph of Raphael Aninat by a faux Grecian pool and robed in a spa white towel, it is the purest version of Raphael Aninat best remembered by those that loved him – and a memory which the author helped to make. Pictured to Aninat’s right, a few inches taller and in a matching towel, stands Sergei Boissier. He is the best friend that survived.

Since 2017, The Aids Memorial has provided a platform that curates a collective memory. Its founder, Stuart, set it up with the very intention of remembrance. “It kind’ve just happened. Obviously if you’re gay and of a certain age – of any age, really – the history is of interest. I did it for myself,” he tells me over the phone on an afternoon when the brief British heatwave was at its most blistering. “People slowly engaged from there, and then started sending tributes to their loved ones on the back of that. It was really nice.”

Today, the project has amassed over 180,000 followers that engage, share and double tap the legion stories that are often deeply intimate. And, as the storytellers recount happier times, or an enduring, aching sense of loss, they are often deeply heartbreaking. One notable entry concerns a couple that bond over Simon & Garfunkel’s “Old Friends/Bookends”, seeing themselves grow old together, like in the song, only for the surviving partner to lament the hours they now spend alone. Another sees a young girl count down the days till she can leave California and move in with her beloved and talented Uncle Richard in New York. He is eventually diagnosed with HIV and returns home, the memory of “him trying to eat a meal and throwing it up seconds later” still raw.

Each post is in keeping with The Aids Memorial’s dedication to the human element of the HIV epidemic. The seemingly never ending tapestry of smiling faces is illustrative of the sheer magnitude of the crisis. It is a tribute removed from statistics, because statistics are inarticulate. As the globe has undertaken a grim crash course in infection numbers and death rates, daily news reports elicit a momentary wince before audiences move on entirely. Figures like ‘140,000’ are big, and impactful, but so large are they that they often feel abstract, too unwieldy to extrapolate anything from, now too commonplace to shock. When a surviving relative barely holds back tears on BBC News, only then do we feel it in our chest. Those real stories – like those of The Aids Memorial – can be overshadowed by the statistics, and the statistics alone only tell part of the story.

Compare Covid-19 to that of the Aids crisis. While coronavirus has undoubtedly ripped through the planet, aids.gov reports that around 35 million people have died of HIV-related illnesses since 1981 – almost nine times the standing worldwide death toll of the entire coronavirus pandemic. In the millions is where human stories are almost lost entirely. “There’s a wide range of people involved who, to this day, are still ignored. That’s an eye opener,” says Stuart. “There are a lot of reports of the discovery of HIV in the Eighties, but it came before that. Robert Rayford was a suspected sex worker who may have been the earliest confirmed case in the Sixties. There are so many stories that have been forgotten.” Stuart pauses. “But that’s not unusual, because people just seem to know very little.”

At its height, the Aids crisis was rarely afforded a speaking role on the national stage. In the 2015 documentary short, When Aids Was Funny, audio clips reveal Ronald Reagan’s press secretary joking about the epidemic with members of the media. Despite soaring and silent infection rates that climbed during the sexual revolution of the Seventies, the American president didn’t even mention the word “Aids” until 1985. At that point, over 12,0000 people had died and the virus was openly circulating in both haemophiliac and IV drug user populations. In the UK, then prime minister Margaret Thatcher found public health warnings against ‘risky sex’ to be in poor taste, and an affront to the ‘family values’ platform upon which her Conservative Party had rode to victory. Mark Addison, the prime minister’s private secretary, went as far as to endorse active avoidance from Number 10 on the issue, writing at the time: “My own feeling is that the prime minister should stay clear of Aids, even when it is a question of opening laboratories to help innocent victims… If she is going to do a medical visit, I should prefer to suggest a hospital, or a home for children with incurable diseases etc.”

Governmental non-action was compounded by shame. Though much of the Aids crisis surfaced after the Stonewall Riots of 1969 – a landmark uprising in which queer women of colour lead a fightback against police raids on gay bars in New York City – liberation and equality was still out of reach. Thus, an Aids diagnosis was often seen as a marker of shame. This was a “gay plague”, after all, a crisis in which the biblical overtones were as overt as they were inappropriate given that the overwhelming proportion of patients were gay men. Stories of secret HIV diagnoses are commonplace, as are those of families who apportioned the deaths of sons, brothers and uncles to cancer, or other vague illnesses. Just as political ideology refused to shine a light on the human stories, society was snuffing them out completely. Millions were being forgotten.

Despite years of research and campaigning, Stuart recognises that many people are still uncomfortable with discussion of Aids and HIV. “Some of the reasons why people don’t reach out to The Aids Memorial is that they’re reluctant to tell a story about death, or some people don’t have anyone left to tell their story,” he says. “I mean, did you know that Edinburgh and Scotland was the Aids capital of Europe in the Eighties because of drug addiction and heroin? But Scottish society doesn’t want to talk about it. You’ve got so many Scottish people who died of Aids but because of the stigma attached, they don’t want to be attached, and then we just don’t talk about it.”

If one scrolls through The Aids Memorial, it’s easy to assume that this is an American organisation. Many stories are from New York, San Francisco and New Jersey. Indeed, prior to our first phone call, I assumed Stuart to be American too. My surprise was barely concealed when a soft Scottish accent greeted me on the other line. British stories exist within the project, but they are fewer. “Americans seem to have a far more open culture when it comes to things like this. It’s difficult. Thinking about it, even I might not submit stories of people I’ve lost to a stranger to be exhibited publicly, but it’s so valuable to me that people trust me to share their story,” says Stuart. “Europeans find it difficult to share I think, in that respect.” When I ask Stuart why he thinks that is, he flips it back to me. “There are a lot of reasons why people don’t share, but when people ask why, I put it to them: why don’t you think people are sharing these stories? People are still unwilling to talk about it, which, after all these years, is just so sad.”

Because, ultimately, stigma is a limpet – especially in a society that still struggles to soften its stiff upper lip, and one that long felt uncomfortable with public discussions about sex. But as more and more stories are shared on The Aids Memorial, the enormity of the HIV crisis is realised in full photographic memory. Stuart, who prefers to remain largely anonymous so as not to detract from the individuals of the project, wants to use The Aids Memorial to prove how far reaching the virus is. “With all of these submissions, it came to me that with the Memorial, it’s not just men. It’s women, and children, and babies, and so many of these stories are untold,” he says. “I think it’s expanded my knowledge about who was involved. There was a lot of whitewashing and there were so many more people that didn’t, and still don’t, get recognition.”

Stuart manages the project with sincerity and sensitivity, actively remembering to repost individual stories on birthdays, or on the anniversary of their passing (“they’re just too valuable to be a one-off,” he says). And as someone who has become an archivist and historian in his own right, Stuart adroitly draws clear parallels between Covid-19 and Aids. “You see the nihilism, and the denialism, and people dying alone. It’s also the fact that it affects the most vulnerable in our society, the most marginalised. It affects people in nursing homes, the BAME community. The similarities are all there,” he says. “But the difference is that people are trying to get a fix. A vaccine is already here. We didn’t have that with HIV and nobody wanted to talk about it. People still aren’t talking about it.” At a press conference in 1984, Margaret Heckler, then the US Secretary of Health and Human Services, predicted the arrival of a HIV vaccine in two years time. 37 years later, it has yet to materialise.

The Aids Memorial has published hundreds of individual stories. Remembering and honouring them allows these people to live on, the project using the hashtag #whatisrememberedlives to anchor each entry. When our discussion turns to specific submissions that have been especially impactful, both Stuart and I simultaneously fall upon the story of an East Village bouncer that met the love of his life on the job, only for it to end five years later. Despite several reposts, it is still devastating in its candour and simplicity.

“The stories are endless but one that I cannot erase is bathing Jaime at his weakest and in the last stages of his illness. That very moment, looking at each other, knowing this was it. I felt something shift in my chest. It was my heart literally aching. Fuck I miss him.”