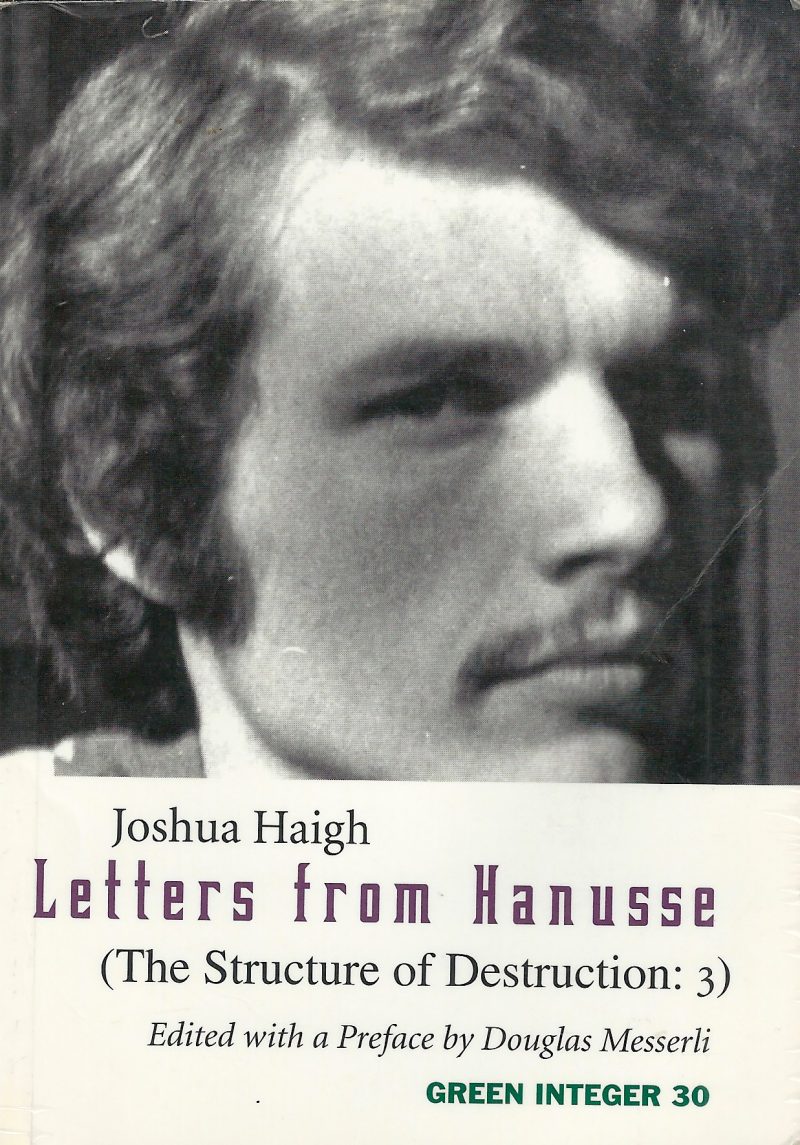

Letters from Hanusse: the Structure of Destruction: 3 Book

Letters from Hanusse: (the Structure of Destruction: 3)

Joshua Haigh, Green Integer, 2000 – Fiction – 291 pages. Editor Douglas Messerli. Dimensions approx. 4 x 5 inches. $25.

Author of numerous works of poetry (most recently First Words), drama (under the name Kier Peters) and fiction, Messerli is the publisher of Green Integer. Author of numerous works of poetry (most recently First Words), drama (under the name Kier Peters) and fiction, Messerli is the publisher of Green Integer.

This volume is the third in The Structure of Destruction, Douglas Messerli’s exploration of evil in 20th century; Letters from Hanusse was written by Joshua Haigh who sent the manuscript to Messerli because of the latter’s writings based on French philosopher/fiction-writer Claude Ricochet, who ultimately plays a character within the work. Through a series of letters Haigh recounts his involvement in the early 1960s with a cult-like group of two married couples as they share a house (in Queens) and sexual favors, and later go underground in Paris. As the narrative progresses it becomes apparent that the writing is heading toward two terrible denouements, one in a Paris cemetery which results in the narrator and children escaping possible death to the contemplative landscape of Hanusse; and the other which may end in their possible destruction in a Hanusse carnival. The story intertwines the lives of figures, real and fictional, to explore the awful heritage and destructive actions of individuals and the culture as a whole in the late 20th century.

From Publishers Weekly

The bohemian demimonde becomes the breeding ground for perverted delusions in this third novel in Messerli’s Structure of Destruction series. Joshua Haigh, the ostensible author of the book (his name appears on the jacket and title page), is a product of the ’60s counterculture. Back in the day, Joshua and his wife, Hannah, lived in a New York City commune that centered around the messianic Leon. Leon encourages free love, which is how Joshua discovers his own appetite for gay sex. Eventually, Hannah and Elizabeth, Leon’s wife, give birth to Ford and Minnie. Joshua’s account of the next stage in the group’s life is fragmented. It seems that Leon fakes the murder of Hannah and Elizabeth, while in actuality fleeing with the women and their children to Paris, where he plans to sell the infants to some rich pedophiles. Joshua, momentarily tricked by the fake murders, soon follows them and succeeds in getting the Parisian police to interrupt the sale and hand the children over to him. Joshua’s account isn’t wholly trustworthy. After all, why would Leon disguise one crime with a greater crime? And Joshua’s motives are suspect: far from saving Ford from pedophilia, Joshua becomes the boy’s lover once he is barely in his teens; by this time Joshua, Ford and Minnie are living in Hanusse, an Aegean state with famously loose morals. These facts are gradually divulged in Joshua’s letters to Hannah, embellished with literary references and fabrications. Fascinated by the artist’s claim to the moral unaccountability of his ego, Messerli succumbs to the treacherous siren song of the counterculture, and saddles his otherwise intriguing novel with an eminently dislikable protagonist. (Feb. 4)Green Integer.

Copyright 2001 Cahners Business Information, Inc.