Ushio Shinohara Signed Tote Bag, Tate Modern, London

Ushio Shinohara Signed Tote Bag, Tate Modern, London. Mint Conditon. Gift from the Artist. Signed and dedicated to me in my name / see photos. Measures 18 inches width x 15 inches depth/height.

Made Exclusively for ‘The EY Exhibition: The World Goes Pop’ at Tate Modern

USD$225.

USHIO SHINOHARA, (1932 – PRESENT)

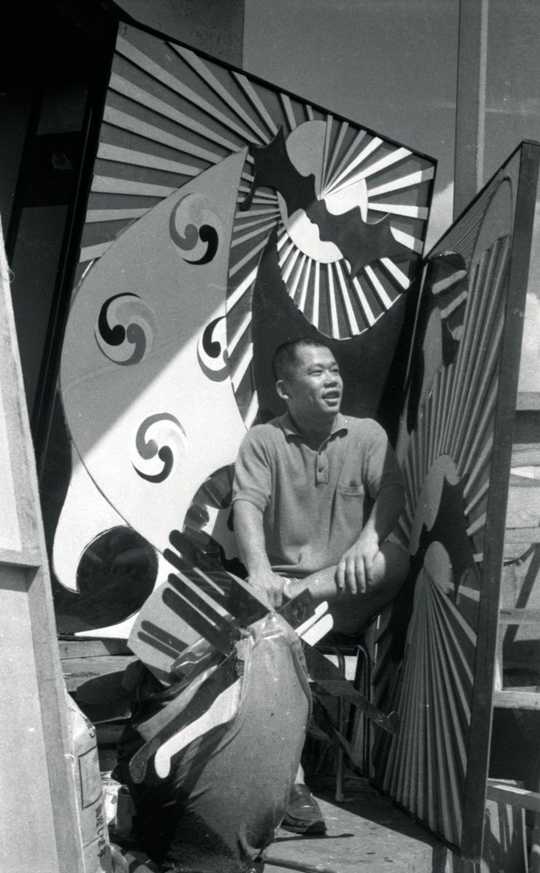

Born in Tokyo in 1932, Ushio Shinohara comes from an artistic family. His father a poet, his mother a nihonga painter and doll maker, Ushio continued the artistic legacy and attended Tokyo University of the Arts in 1952. In 1957, Ushio left the university to pursue his education independently, pouring over international works of art criticism and avant-garde theorists. Ushio entered the 1960s as a force of the Japanese avant-garde art scene with his action paintings. He gained particular notoriety for his abstract boxing paintings. Attaching sponges to his boxing gloves, Ushio would saturate the gloves with paint and punch his way across a long paper or canvas. In 1963, Ushio Shinohara discovered a deep and lasting inspiration in the American avant-garde on the pages of Art International and promptly began his Imitation Art series (1963).

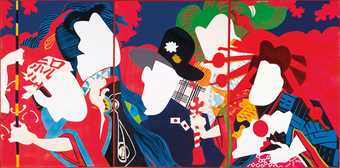

In 1965, Ushio combined his American influences with Japanese tradition. Upon seeing woodblock prints from the Edo period, Ushio created his Oiran series, blending the iconography of Edo-period courtesans with the vivid colors and geometric shapes so popular within American Pop art. In 1969, Ushio moved to New York City on a scholarship from the John D. Rockefeller III Fund. Though the scholarship ended after a year, he made New York his permanent home. He has participated in exhibitions at the Tate Modern in London, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo, the Japan Society in New York, and the Guggenheim Museum SoHo, to name just a few. Ushio Shinohara’s artwork can be found in permanent collections such as the Museum of Modern Art New York and the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto. Ronin Gallery is proud to present a selection of Ushio Shinohara’s abstract artworks.

ARTIST INTERVIEW: USHIO SHINOHARA

Was ‘pop art’ a term used by yourself or colleagues or was there a different terminology that referred to a new figurative art movement in the 1960s and early 1970s?

In the early 1960s, the term pop art was very fashionable; however, after just a few years, op art, conceptual, and environmental art, which had developed a bit later, took over and the term became an out-dated fashionable term.

Did you ever consider yourself (now or in the past) a pop artist?

I have never thought of myself as a pop artist. At the time, I just gave up my drawing and brushstroke skills and started using a stencil method.

Did your work engage with current events in the 1960s and early 1970s?

When creating works, I always intend to ride the flow of the world and fight at the front. Of course I also joined the flow at that time.

Ushio Shinohara

Doll Festival 1966

Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art (Yamamura Collection)

© Ushio and Noriko Shinohara

How did you choose the subject matter for your work included in The World Goes Pop?

It is an honour [that my works will be shown in the exhibition]. At that time I put all my energy into this group of works. The fact that I will be able to see them in an international group exhibition makes me happy beyond words.

Where did you get your imagery from (what, if any, sources did you use)?

I was inspired by Japanese wood block prints from the Edo period [1603–1868].

Were you aware of pop art in other parts of the world?

I care very much. I would especially like to see sculptures by pop artists. It is not enough that there are works by Oldenburg and George Segal.

Was commercial art an influence on your work or the way in which it was made?

Commercial art does not allow an artist to be too self-centred and self-satisfied. . It is therefore attractive to lonely artists who are working by themselves in their studio.

Was there a feeling at the time that you doing something important and new, making a change…?

During the opening of the Tokyo Olympics in 1964, the whole of Japan was very excited. All of us young artists were feeling a sense of fulfilment while creating works.

Was there an audience for the work at the time – and if so what was their reaction to it?

The Japan of that time did not have any art dealers. We as artists organised group exhibitions to present our works and only related people from the art world were excited about them. There were no collectors, either.

Looking back at these works, what you do think about them now?

I was at the height of my youth. I was full of youth and energy, fresh ideas and a strong feeling of curiosity about America and Europe. The decade was like a rainbow and today there are only a few works left from that time so these are really precious.

September 2015

The World Goes Pop

Time Out says

Over 200 works by artists from Latin America to Asia celebrates the many faces of pop art.

This show isn’t about the pop art you know, it’s about the pop art that escaped the history books. And it certainly packs a punch. It’s fun, engaging, colourful, revelatory, opinionated, racy and stunning. Most importantly the show illuminates how pop wasn’t confined to Andy Warhol’s Factory in New York or Richard Hamilton’s studio in London – it was a phenomenon that reached much further, practiced by artists in Peru, Israel, Argentina, Japan, Brazil and Eastern Europe.

In an opening gallery painted scintillating red, the work quite literally pops off the walls. Here, traditional techniques are turned on their head, such as Japanese woodblock printing in Ushio Shinohara’s ‘Doll Festival’, (1966) which is reinvigorated with the use of industrial materials like Perspex.

Moving on, you’ll find the mimicry of media and the language of mass production, the repetition of advertising strategies and consumerist logos, the appropriation of icons from popular culture, the re-evaluation of the role of women and the subversion of political symbolism. It makes for a riveting, eye-opening group exhibition that re-educates us on a movement that really reached out to embrace us – and continues to do so.

The Brazilian military dictatorship of the 1960s is confronted in Marcello Nitsche’s giant flyswatter, ready and waiting to squish the tyrannical regime. Pop stars from western magazines are reimagined as the friends of Romanian artist Cornel Brudaşcu in his exquisite paintings. Basically everywhere you turn, the work is assessing the social, cultural and political terrain in which it was created.

Women artists have been most notably omitted from the canon of pop art, so it’s reassuring that the two female curators have made sure to rebalance the status quo. Naked women become domestic white goods in Martha Rosler’s brilliantly critical photomontages. Judy Chicago’s electric car hoods, emblazoned with female anatomy, are concisely hung in a small gallery dedicated to ‘folk pop’, though it’s a category the show perhaps could have done without.

The voice of the people is heard most loudly in a large gallery near the end of the show given over to the ‘pop crowd’. Here the energy of political disillusionment ricochets around the walls, especially in Henri Cueco’s ‘Large Protest’ (1969) whose cut-out abstracted figures stride towards revolution.

Pop proves to be a truly universal language, one that gave artists the impetus to create works that are as stimulating intellectually as they are visually. No longer will these artists be footnotes to the Anglo-American pop art story because here, rightly, they take centre stage.

RECOMMENDED: Read our full guide to ‘The World Goes Pop’ at Tate Modern

PRESS:

https://www.timeout.com/london/art/the-world-goes-pop-at-tate-modern-your-ultimate-guide

Bibliography:

– Ushio Shinohara Exhibition Catalogue+, Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art, Mainichi Shimbun, 1992

– Avant-Garde Art in Postwar Japan+, Yokohama Museum of Art, The Yomiuri Shimbun, 1994

– Ushio Shinohara – Boxing Paintings and Motorcycle Sculptures, The Museum of Modern Art, Kamakura & Hayama, 2005

– Dialogues with Ushio Shinohara – Quickly, Beautifully, and Rhythmically+, Bijutsu Shuppan-sha Co., Ltd., 2006

– Ushio Shinohara Exhibition: Gyu-chan, 60 Years of Roaring on the Avant-garde Road, Kariya City Art Museum, 2017

– Ushio Shinohara, editing by Keiichi Tanaami, From Ushio Shinohara to Keiichi Tanaami, 50 Years of Correspondence+, Tokyo Kirara, 2021

– Oral History Archives of Japanese Art, Ushio Shinohara Oral History+, February 13, 2009

[http://www.oralarthistory.org/archives/shinohara_ushio/interview_01.php]

*Titles marked with a plus sign (+) are tentative translations.

Ushio Shinohara

Born in Tokyo, 1932. Lives and works in New York, USA.

During his time studying at Tokyo University of the Arts majoring in Yōga (western-style painting), Shinohara apprenticed to Takeshi Hayashi, and participated in the Yomiuri Independent Exhibition, which made his rise to stardom. After leaving the university, Shinohara established the group “Neo Dada Organizers” with Masanobu Yoshimura in 1960. Despite a short time period of activity as a group, their phenomenal and radical performances have brought significant impact upon Japanese art scene. In 1969, he received a fellowship from The JDR 3rd Fund to spend a year in the United States. Ever since, his large-scale paintings from a vibrant color palette and Shinohara’s energetic “Boxing-Painting” attracted significant attention nationally and internationally. In 2007, he received the 48th Mainichi Art Award for his long-standing achievement. Ushio and his wife Noriko Shinohara debuted in a film “Cutie and the Boxer” directed by Zachary Heinzerling, and it was nominated in 2014 for the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature at the 86th Academy Awards. In 2015, he participated in the exhibition “International Pop” organized by and toured from Walker Art Center, Dallas Museum of Art, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art through 2016, followed by the exhibition “The World Goes Pop” at Tate Modern in the same year. After 10 years, he returned to Japan with his solo exhibition presented at YAMAMOTO GENDAI in Tokyo, featuring a signature boxing performance/painting at the opening. Shinohara still remains as one of the respected artists representing Japan.

As one of the outstanding artists living today to represent the country, his energetic presence is everlasting with more recent solo exhibitions including “Shinohara Pops! The Avant-Garde Road, Tokyo/New York” The Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art, NY (2012) and “Gyu-chan, 60 years of roaring on the avant-garde road” Kariya City Art Museum, Aichi (2017) along with the group exhibitions “Parody, around 1970s right and left of double voice – – Japan” Tokyo Station Gallery (2017) and “1968: Art in the Turbulent Age” Kitakyushu Municipal Museum of Art, Chiba City Museum of Art, Shizuoka Prefectural Museum of Art, The Museum of Art, Kochi (2018).

Collection

MoMA, New York, US

Musee d’art contemporain de Montreal, Canada

Musée d’art Contemporain, Lyon, France

National Gallery Prague, Czech Republic

Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, Japan

Hara Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, Japan

Itabashi Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan

The National Museum of Art, Osaka, Japan

etc.