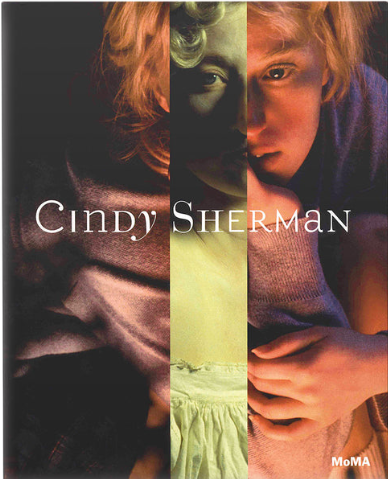

‘Cindy Sherman’ MOMA 2012

“I wish I could treat every day as Halloween, and get dressed

up and go out into the world as some eccentric character.”

– Cindy Sherman

- Publisher : The Museum of Modern Art, New York; First Edition (February 29, 2012)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 264 pages

- Item Weight : 4.63 pounds

- Dimensions : 9.8 x 1.2 x 12.2 inches

Asking USD$95 / Still Sealed in Original Plastic Wrapper / Never Been Opened / MINT

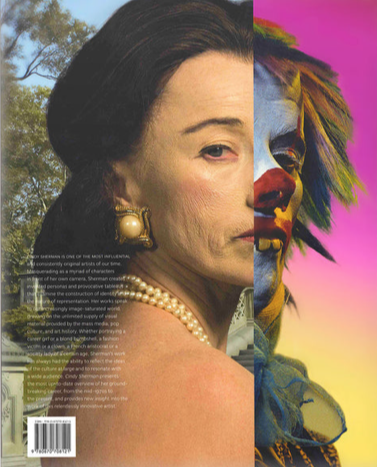

A comprehensive monograph on one of the most important and influential artists of our time, accompanying MoMA’s major 2012 Cindy Sherman survey

Published to accompany the first major survey of Cindy Sherman’s work in the United States in nearly 15 years, this publication presents a stunning range of work from the groundbreaking artist’s 35-year career. Showcasing approximately 180 photographs from the mid-1970s to the present, including new works made for the exhibition and never before published, the volume is a vivid exploration of Sherman’s sustained investigation into the construction of contemporary identity and the nature of representation. The book highlights major bodies of work including her seminal Untitled Film Stills (1977–80); centerfolds (1981); history portraits (1989–90); head shots (2000–2002); and two recent series on the experience and representation of aging in the context of contemporary obsessions with youth and status. An essay by curator Eva Respini provides an overview of Sherman’s career, weaving together art historical analysis and discussions of the artist’s working methods, and a contribution by art historian Johanna Burton offers a critical re-examination of Sherman’s work in light of her recent series. A conversation between Cindy Sherman and filmmaker John Waters provides an enlightening view into the creative process.

Eva Respini is a former Curator in the Department of Photography at The Museum of Modern Art, New York where she contributed to numerous publications including Robert Heinecken: Object Matter (2014); Cindy Sherman (2012); and Into the Sunset: Photography’s Image of the American West (2009); Fashioning Fiction in Photography since 1990 (2004).

John Waters is an American filmmaker, actor, writer, and visual artist best known for his cult films, including “Hairspray”, “Pink Flamingos”, and “Cecil B. DeMented”. He lives in Baltimore, Maryland.

Johanna Burton has served as the director of the graduate program at the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College.

See Exhibit:

https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1154

Reviews:

At many points throughout this dense, often exciting show .… we are confronted by an artist with an urgent, singularly personal vision, who for the past 35 years has consistently and provocatively turned photography against itself. She comes across here as an increasingly vehement avenging angel waging a kind of war with the camera, using it to expose what might be called both the tyranny and the inner lives of images, especially the images of women that bombard and shape all of us at every turn.

Although not one of her images qualifies, exactly, as a self-portrait, the Modern’s show is above all an inspiring portrait of the artist ceaselessly at work, striving never to repeat herself, always trying to go deeper and further in one direction or another. Her self – remorseless, generous, imaginative and shrewd – is everywhere. — Roberta Smith ― The New York Times

Ever since her student efforts in the 1970s, she has been exploring the complex territory of constructing a self for the camera – a focus that placed her squarely at the forefront of postmodern theory. Nevertheless, it is still surprising to see the great variety of work she has produced from this single-minded inquiry. Her landmark achievement, “Untitled Film Stills,” created between 1977 and 1980, surveys the history of women in cinema, using little more than makeup and wigs. — Barbara Pollack ― ARTnews

No feature of a Sherman image is there by accident or as a matter of convenience. These grand backdrops are legacy monuments of the older plutocracy, left as a democratic inheritance, belittling the imagination and attainments of the present-day .01 percent. As her own works have come to count among the prized trophies of that demographic, Sherman seeds into these images a grandeur belonging to a past that no private individual can now claim or master. — Thomas Crow ― Artforum

Cindy Sherman has explored different kinds of photography, but she has become one of the most lauded artists of her generation for her photographs of her impersonations. Since she arrived on the scene, in a 1980 exhibition, when she was in her mid-twenties, she has come before her own camera in the guise of hundreds of characters, and as an impersonator–which in her case means being a creator of people, and sometimes people-like creatures, who we encounter only in a single photograph–she has been remarkably inventive. — Sanford Schwartz ― The New York Review of Books

Eva Respini, the curator of the MoMA exhibition and the museum’s curator of photography, begins her catalogue essay with some of the misreadings that have dogged Sherman’s work, and lists the sucessive waves of critical theories that have claimed the artist as their own, including “postmodernism, feminism, psychoanalytic theories of the male gaze and the culture of the spectacle”. — Liz Jobey ― The Art Newspaper

This overview is the most comprehensive to date because it clearly documents transformations in [Cindy Sherman’s] well-known serial self-portraiture. Sherman is celebrated as the quintessential conceptual artist who uses photography. In an essay, exhibition curator Respini describes Sherman as an artist who fully represents today’s prevalent “culture of the cultivated self.” More adeptly than past writers, Respini firmly situates Sherman among contemporaries like Eleanor Antin, Hannah Wilke, Suzy Lake, and Adrian Piper…Highly recommended. — M. R. Vendryes ― Choice

A more than 30-year survey of Sherman’s roles in front of the camera (movie star, housewife, aristocrat) and behind it (photographer, art director, stylist). ― American Photo

MORE:

For four decades, Cindy Sherman has probed the construction of identity, playing with the visual and cultural codes of art, celebrity, gender, and photography. She is among the most significant artists of the Pictures Generation—a group that also includes Richard Prince, Louise Lawler, Sherrie Levine, and Robert Longo—who came of age in the 1970s and responded to the mass media landscape surrounding them with both humor and criticism, appropriating images from advertising, film, television, and magazines for their art.

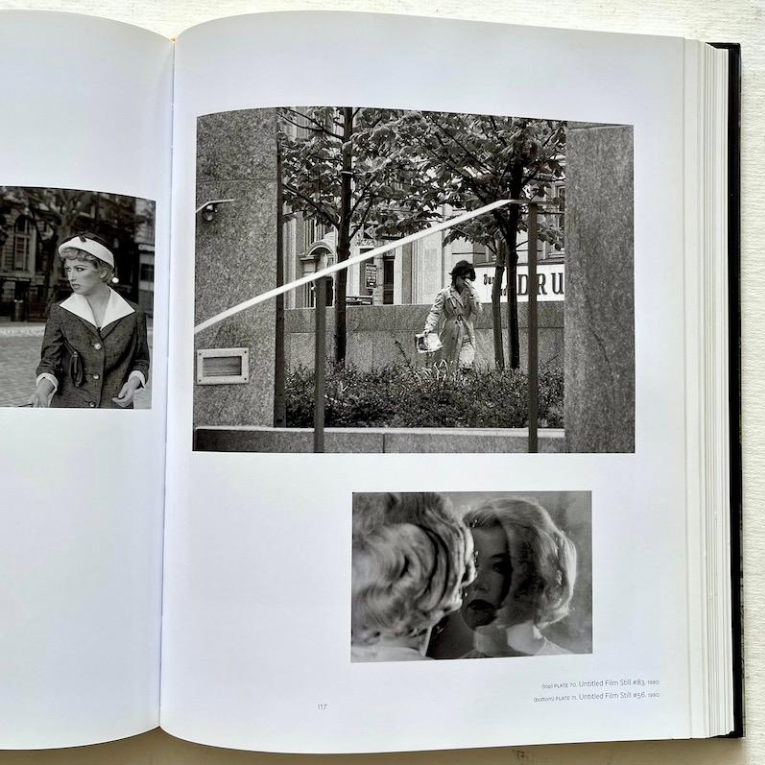

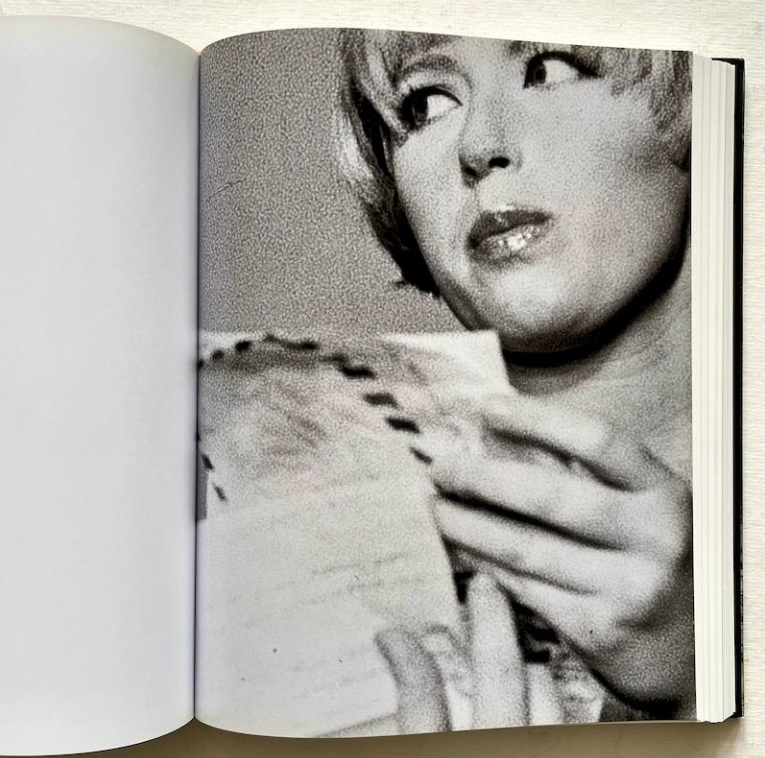

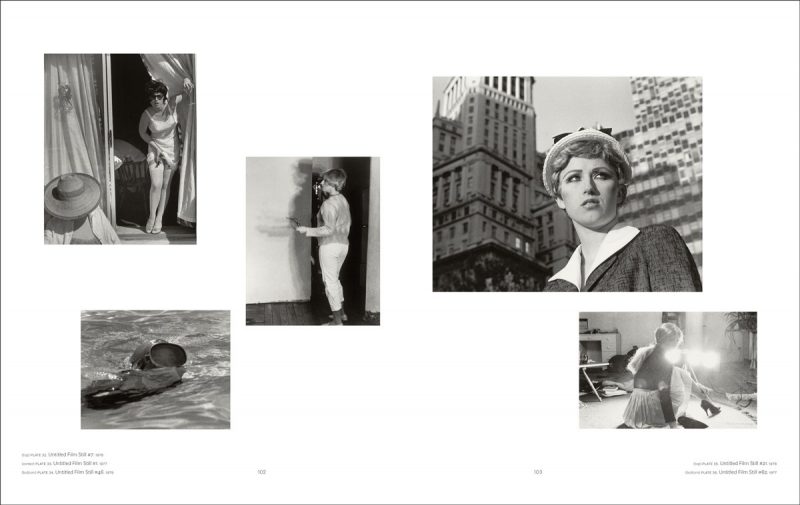

Sherman was always interested in experimenting with different identities. As she has explained, “I wish I could treat every day as Halloween, and get dressed up and go out into the world as some eccentric character.”1 Shortly after moving to New York, she produced her Untitled Film Stills (1977–80), in which she put on guises and photographed herself in various settings with deliberately selected props to create scenes that resemble those from mid-20th-century B movies. Started when she was only 23, these images rely on female characters (and caricatures) such as the jaded seductress, the unhappy housewife, the jilted lover, and the vulnerable naif. Sherman used cinematic conventions to structure these photographs: they recall the film stills used to promote movies, from which the series takes its title. The 70 Film Stills immediately became flashpoints for conversations about feminism, postmodernism, and representation, and they remain her best-known works.

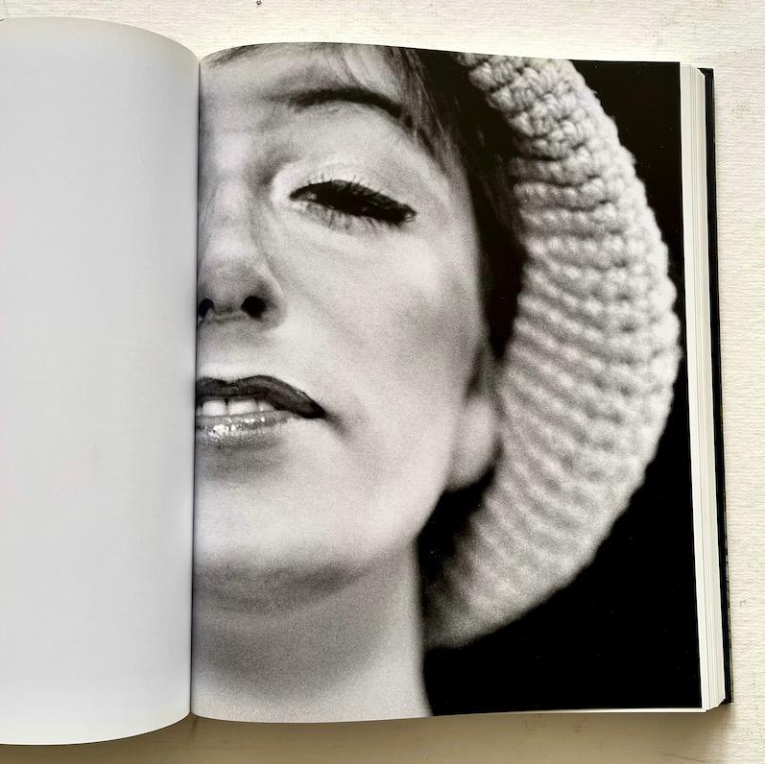

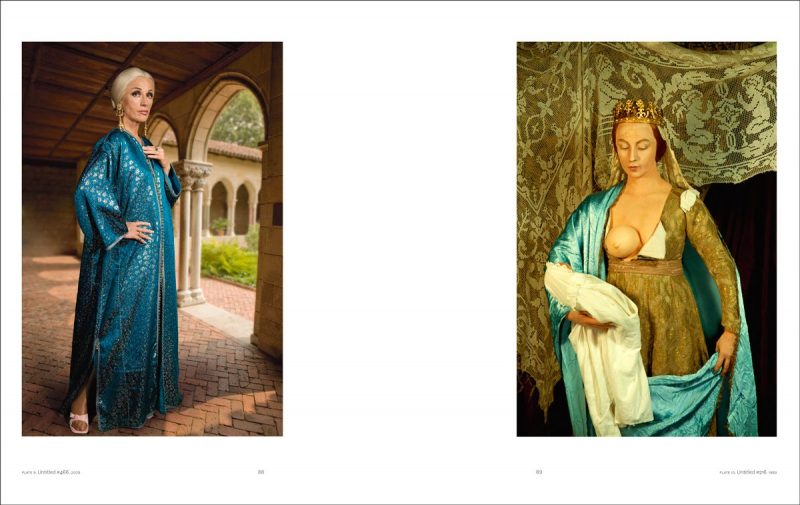

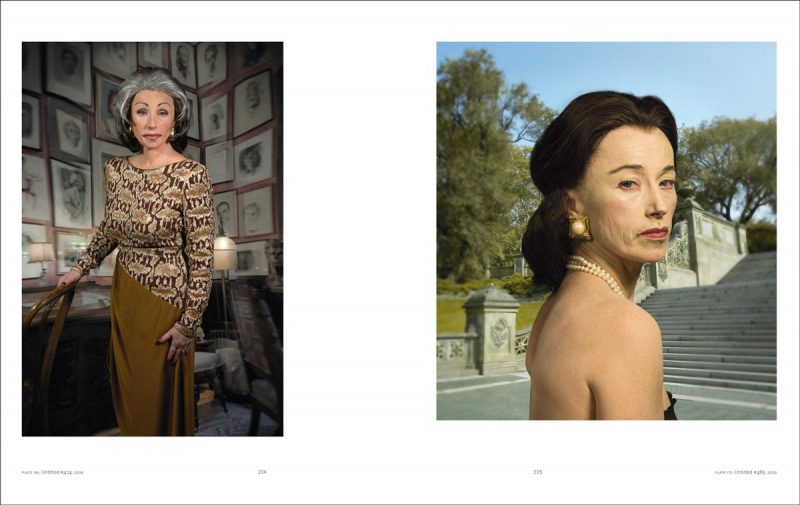

Sherman has continued to transform herself, displaying the diversity of human types and stereotypes in her images. She often works in series, improvising on themes such as centerfolds (1981) and society portraits (2008). Untitled #216, from her history portraits (1981), exemplifies her use of theatrical effects to embody different roles and her lack of attempt to hide her efforts: often her wigs are slipping off, her prosthetics are peeling away, and her makeup is poorly blended. She highlights the artificiality of these fabrications, a metaphor for the artificiality of all identity construction.

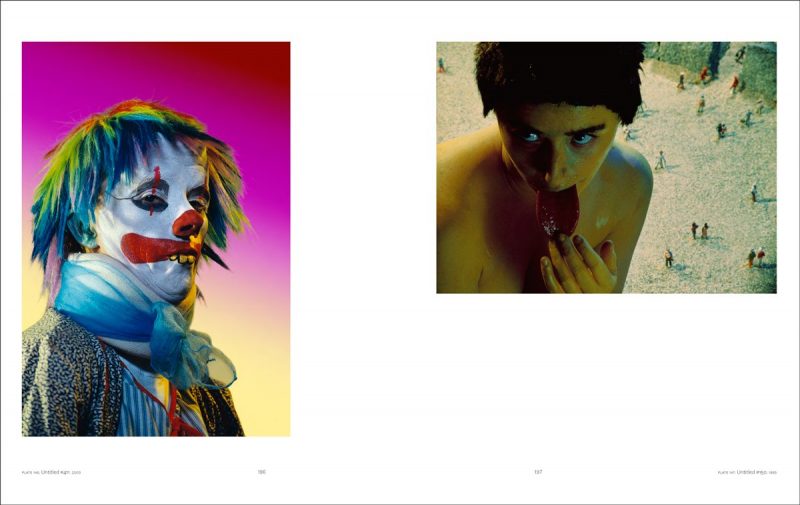

While she sometimes portrays glamorous characters, Sherman has always been more interested in the grotesque. In the 1980s and 1990s, series such as the disasters (1986–89) and the sex pictures (1992) confronted viewers with the strange and ugly aspects of humanity in explicit, visceral images. “I’m disgusted with how people get themselves to look beautiful; I’m much more fascinated with the other side,”2 she said in 1986. At the time, images of ailing bodies were painfully on view in the news during the AIDS crisis; these added poignancy to her investigation of the grotesque and of various types of violence that could be done to the body. In these series and throughout all of her work, Sherman subverts the visual shorthand we use to classify the world around us, drawing attention to the artificiality and ambiguity of these stereotypes and undermining their reliability for understanding a much more complicated reality.

Cindy Sherman

IN THE ANGLO-AMERICAN museum world, this past winter might well have been called the season of the portrait. That theme announced itself in London, at the National Gallery’s incomparable Leonardo exhibition, in which the gathering of portrait subjects scattered from Paris to Krakow upstaged even the epochal pairing of the Louvre’s Virgin of the Rocks with its London replica. A month later in New York, the Metropolitan Museum of Art opened “The Renaissance Portrait from Donatello to Bellini,” an assembly of fifteenth-century images that brought to an extraordinary semblance of life its cast of northern Italian courtiers and prodigies of financial manipulation from the dawn of our modern banking system. Then, in winter’s waning weeks, the Museum of Modern Art in New York mounted a contemporary rival to the masters in its opulent retrospective for Cindy Sherman.

To align Sherman’s work with antecedents in the realms of gaudy dynasties and gilded frames would seem counter to the received wisdom that the artist has, since the mid-1970s, sought to “examine the construction of identity, the nature of representation, and the artifice of photography,” as an introductory wall label informs the visitor. There is little to dispute in this well-meant instruction; after some three decades in circulation, however, the formula lacks a certain excitement. Not so the exhibition, which makes the sweep of the artist’s career boldly compelling by treating Sherman’s work more as a body of resplendent objects than as a catalogue of images. A portrait, before its denatured insertion into the modern museum, first serves as heirloom or trophy. MoMA’s retrospective pays homage to this double nature of the genre, changing the argument away from what can be said about facsimiles on the printed page and toward what can be absorbed in ambulatory passage through a looming, uncanny ancestral gallery—family resemblances being a given where Sherman is concerned.

Striking choices of wall color punctuate the visitor’s processional movement through the labyrinthine enfilade of MoMA’s sixth-floor exhibition space in a way that surpasses in cognitive effect the alternating pale and somber rooms of the Met’s “Renaissance Portrait.” Each vibrant but complex color choice in the Sherman installation plays an active part in distinguishing and enriching the category of work placed against it. The same can be said for the use of frames, which carry a defining importance that can only be seen in the physical exhibition: The catalogue images, no matter how fine the resolution, necessarily leave out the crucial data of physical presentation, thus inevitably encouraging the familiar mediacentric bias elevating the reproducible image over the finite physical object.

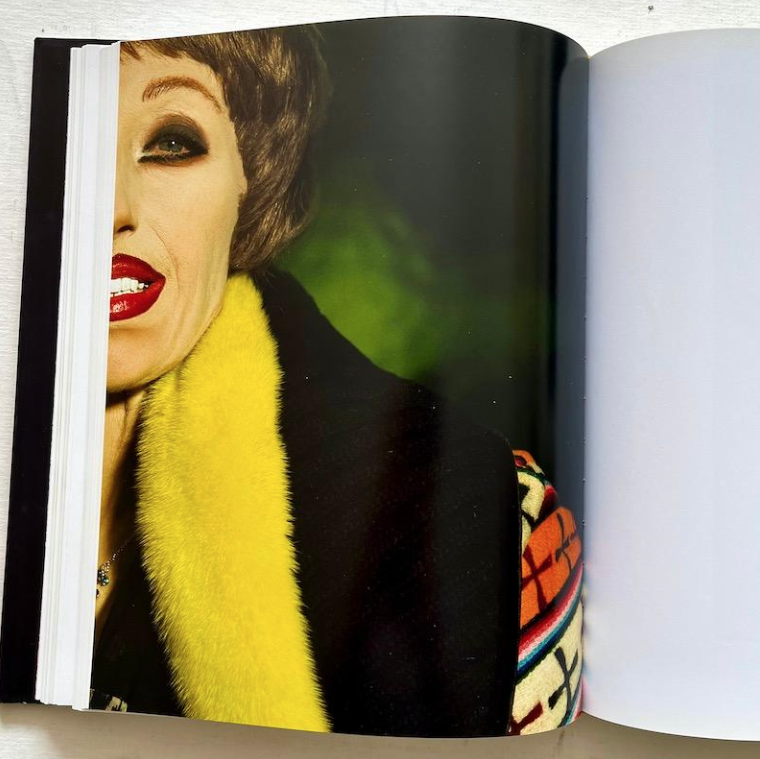

The museum’s complete set of eighty-three “Untitled Film Stills,” 1977–80, with its youthful, shape-shifting protagonist, plays out against a subtle but telling transition to muted pale blue from the standard white of the introductory room, which offers a smattering of pieces from different periods. The concluding space, monumentally scaled, and saturated with a rich blue-green, holds the larger number of the recent, imposing portraits of aging society women in their costly array. This same stately hang reaches back over implied centuries to the central room, painted a deep red—the heart of the exhibition—in which Sherman’s tributes to the old masters, her “history portraits,” climb the walls in an approximation of the densely packed, palatial displays of the pre-museum age.

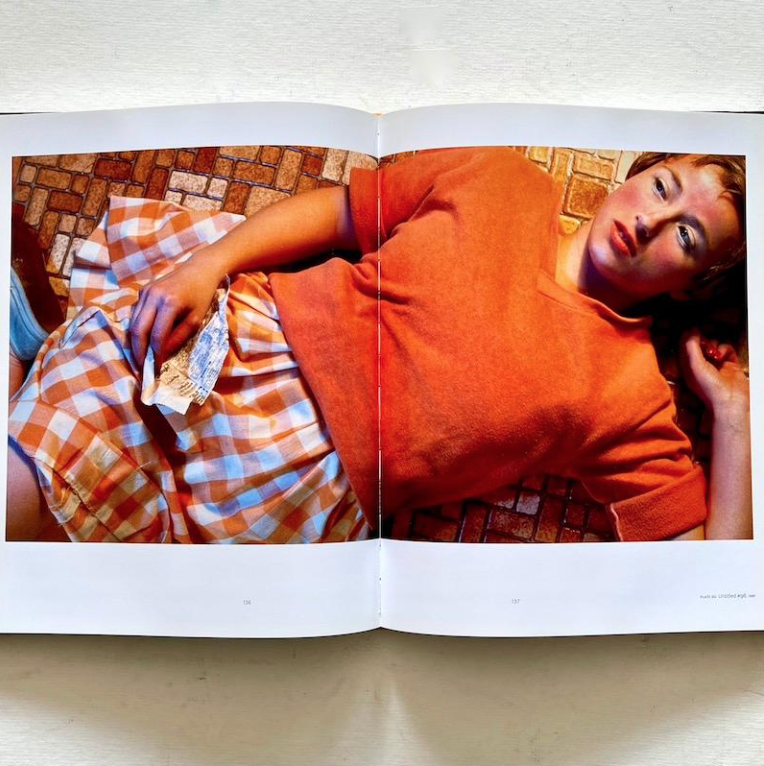

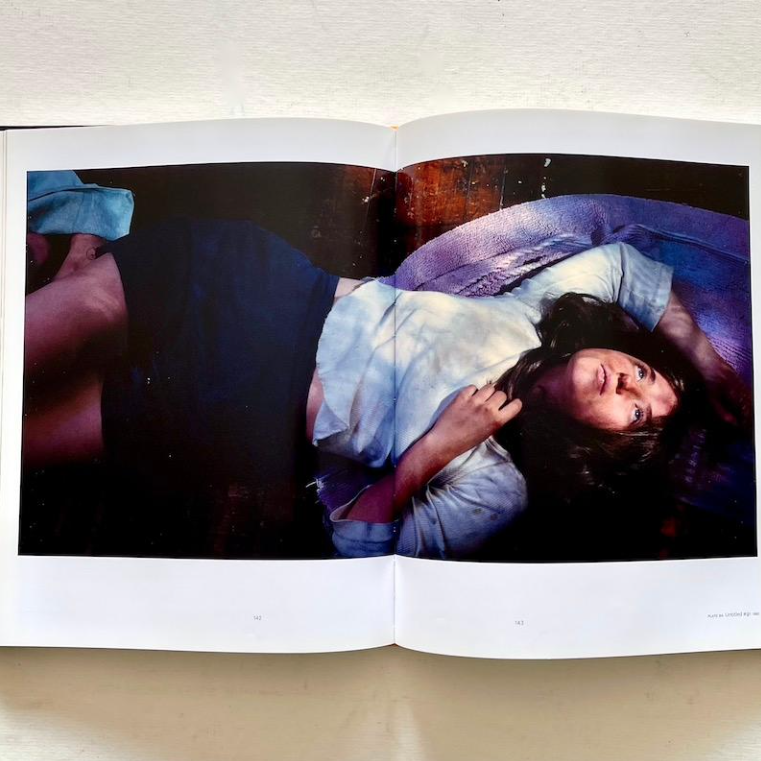

Between the film stills and the historical pastiches lies a dramatic interior room devoted to the so-called “Centerfolds,” 1981, the horizontally oriented color prints Sherman produced for this publication in 1981. Lined up against a dark blue tending to gray, each photograph in a crisp black frame, the series leaves behind the dated “controversy” over its subjects’ imagined abject victimhood. While some of the images present parodies of the fearfully submissive poses that once titillated consumers of B movies and pulp paperbacks, the pictures taken as a whole manifest a modern anatomy of melancholy. The dress may be contemporary to its time, but the rubric is one of an archaic allegory. With such a prototype in mind (witting or unwitting), it should not have been surprising that Sherman would stage her own competition with the old masters by the end of that decade—a series that the exhibition marks off with both a deep crimson sonority and a calculated assortment of framing stock, each art-historical pastiche contained by a variant of traditional molding, some enhanced with gold or silver pigment. But none displays, as might be expected, any further ornament. That distinctive feature is reserved for the large-scale portrayals of ostentatious society matrons in our own time.

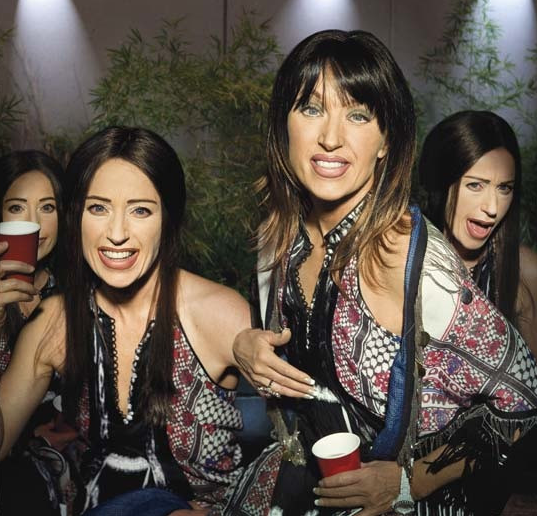

This precise grammar of the frame, doubtless the artist’s undertaking but underscored by the museum’s choices, can be used to differentiate works that might otherwise be easily lumped together. In the smaller alcove adjacent to the grand green room, two similarly sized works—Untitled #475, 2008, and Untitled #463, 2007–2008—hang together, both featuring multiple personages. In the first, Sherman splits herself into two women, one seated and one standing, who together face the camera in stilted poses and stiff hairdos, an empty banquet-size hall with Persian rug stretching behind them. In the other, Sherman appears as no fewer than four figures, all with long dark hair belying the signs of age in their faces and hands, red plastic beer cups in hand—though three of them seem suspiciously identical. The implication in both works is that we are looking at sisters, and both of these fictional ensemble portraits were completed in the same year. But unlike the picture of the presumed twins (#475), Sherman’s sororal coven of keg partiers is contained in a plain white, crisply modernist frame. The same is true of the single figure in Untitled #458, 2007–2008, hands on hips, whose heavily masklike makeup and expensive frock and jacket might otherwise seem aligned with cognate works framed in ornamented mahogany.

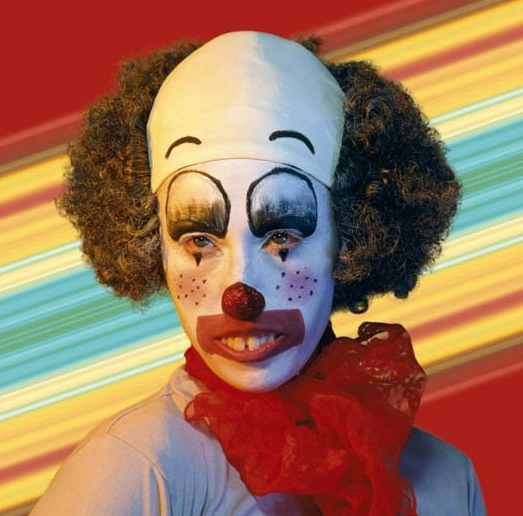

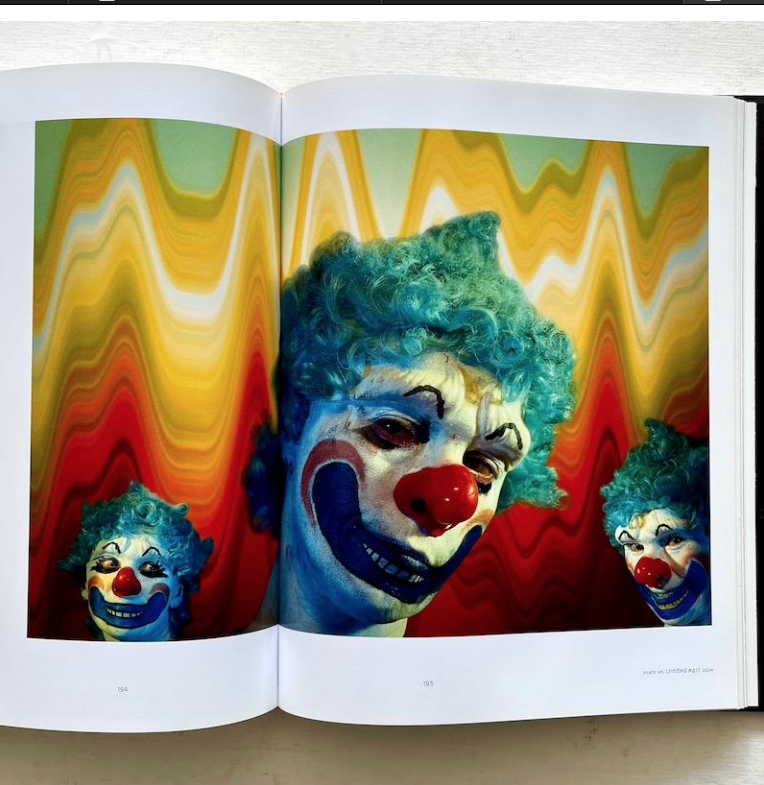

Neither the catalogue nor the wall labels make it easy for the uninitiated viewer to comprehend that the white-framed works were part of a commercial commission, a fashion spread of Balenciaga designs shot for Paris Vogue. In the traditional hierarchy of European art, both #463and #458 conform to the intermediate rank of genre painting, that is, the portrayal of anonymous types rather than known individuals. These works share their white frames with Sherman’s pictures of clowns, and thus align themselves more with mordant comedy than with the marking of social distinction (the original meaning of clown being “rustic, boor, peasant”). The ensemble of four figures counts indeed as a modern-dress equivalent of the standard seventeenth-century Dutch scene of

tavern drinkers: Sherman’s picture may seem jolly, but it is more than a little menacing in its undercurrents, the drunkenly slack mouth of the sister on the far right evoking the louts of Adriaen Brouwer forward to Goya’s sorcery-addled plebs.

The portraits in the higher genre, by contrast, take as their brief the projection of power and success through orchestrated accessories as much as through the unnatural cult of ageless beauty so conspicuous in our era. With age comes authority, and these individuated women of means embrace its heraldic emblems—jewelry, coiffure, cosmetics, couture, and real estate—as fair compensation for losing the unbidden gifts of callow youth (though the strain shows in their reddened eyes). The well-turned, slippered foot that emerges from beneath the brocaded satin caftan in Untitled #466, 2008, carries a pedigree that trails back to the delicate turn of ankle that Hyacinthe Rigaud choreographed for Louis XIV. That Sherman has, with sheen of support stockings and cheapness of spangly footwear, introduced a clash of class signifiers only emphasizes the genealogy of the device by emphatic reversal and factitious resemblance.

These portraits thus resume in contemporary dress Sherman’s overt rehearsals of old-master poses and symbols from two decades before. But these are simulations of a portrait genre that no longer exists—or at least cannot be seen in public confines able to confer the sort of prestige bestowed by display at MoMA or the Met. Sherman provides our not-ready-for-prime-time plutocrats with a celebratory genre bearing an aesthetic authority they cannot buy for their own self-representation. True, the wealthy and self-important still commission family portraits, as private clubs and corporate boards honor their chieftains with imperious likenesses on canvas. There is a cadre of well-compensated practitioners of this craft, but their trade has become, in the century since John Singer Sargent, an almost disreputable embarrassment. Only a vanity museum would ever see fit to expose these journeyman confections to the glare of public scrutiny. Warhol’s late portraits hover just on the edge of legitimate aesthetic attention; the contemporary German Thomases Ruff and Struth have staked a claim for what a credible portraiture of the present day might look like. But their niche is hardly normative, despite Struth’s having been cast as a latter-day Van Dyck in the service of the ruler of Great Britain and her consort on the occasion of the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee.

Sherman’s vanity series features historical monuments of its own. For the softer-focus backdrop behind the caftan-clad matriarch in her immaculate silver bun (#466), she calls on a gothic-style, tiled-roof cloister, which effectively stands in for the revivalist palaces of Montecito or Palm Beach. But the setting is instead an actual medieval edifice imported by a bygone benefactor to stand within the Metropolitan’s Cloisters museum. The glare of the severe-looking woman in Untitled #465, 2008, glancing over her bare shoulder in evening pearls, heavy pancake unsuccessfully masking her incised complexion, seems bolstered by the scale and emptiness of an ornate staircase on the grounds of a grand estate. But this particular garden feature should be among the most familiar monuments of public New York: the steps of Frederick Law Olmsted’s and Calvert Vaux’s Bethesda Terrace, the architectural heart of Central Park, location for a hundred film scenes, playground of multitudes. No feature of a Sherman image is there by accident or as a matter of convenience. These grand backdrops are legacy monuments of the older plutocracy, left as a democratic inheritance, belittling the imagination and attainments of the present-day .01 percent. As her own works have come to count among the prized trophies of that demographic, Sherman seeds into these images a grandeur belonging to a past that no private individual can now claim or master.

“Cindy Sherman,” organized by Eva Respini, is on view through June 11; travels to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, July 14–Oct. 7; Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, Nov. 10, 2012–Feb. 17, 2013; Dallas Museum of Art, Mar. 17–June 9, 2013.

Thomas Crow is a contributing editor of Artforum.