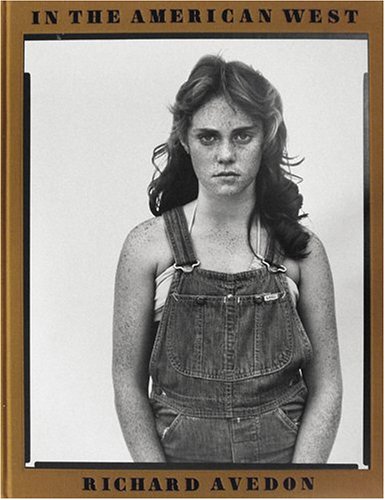

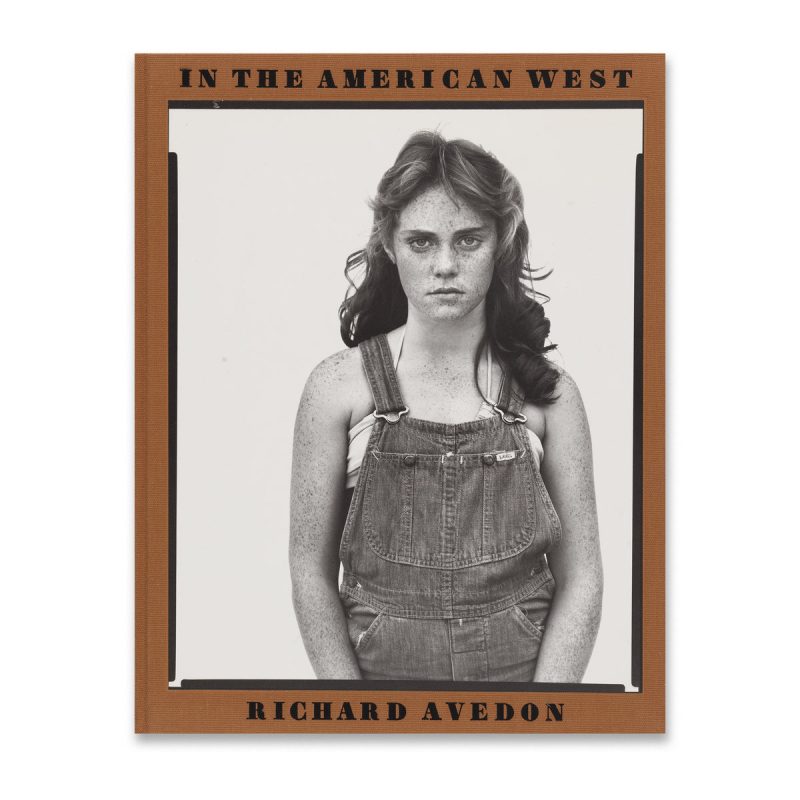

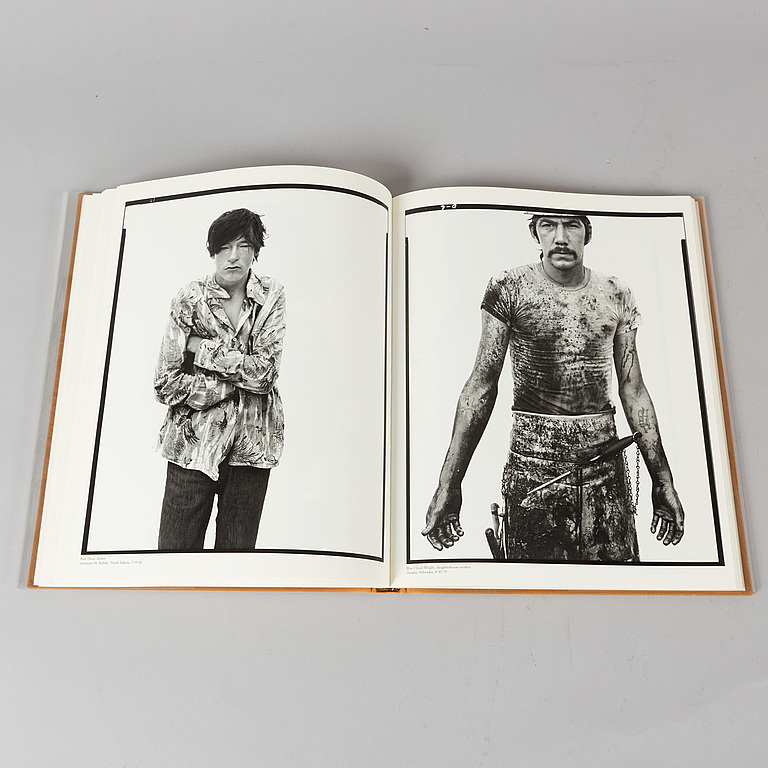

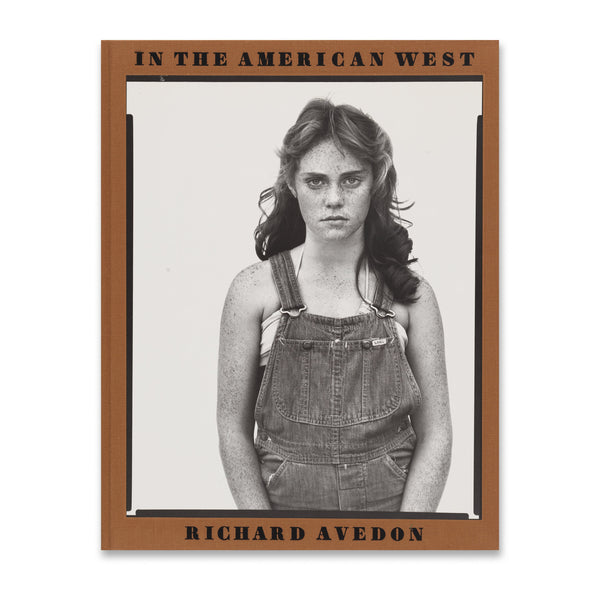

RARE. Richard Avedon: ‘In the American West’ Collector’s First Edition Book, 1985

RICHARD AVEDON: IN THE AMERICAN WEST

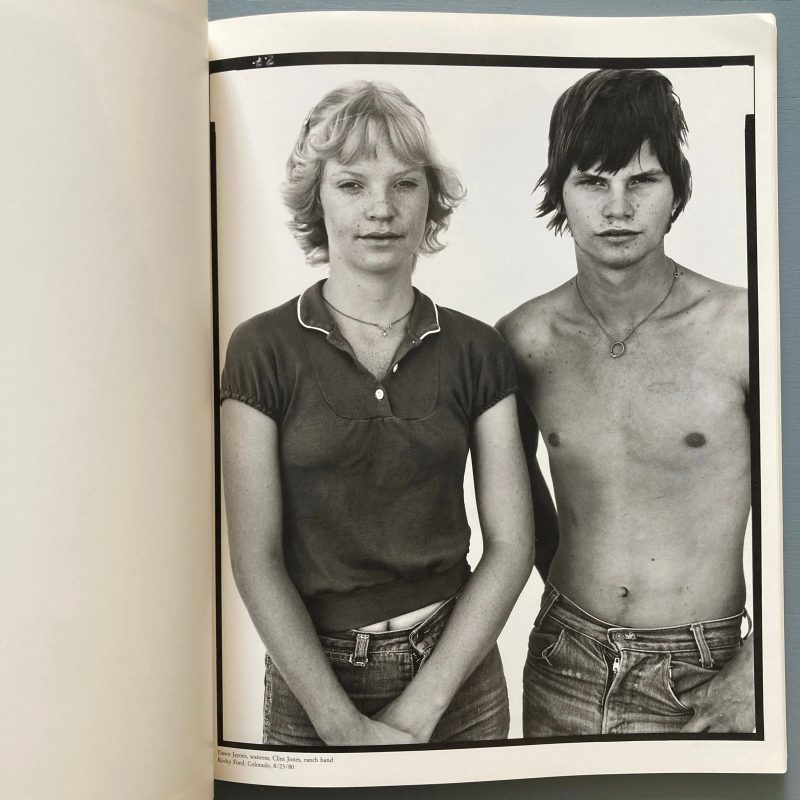

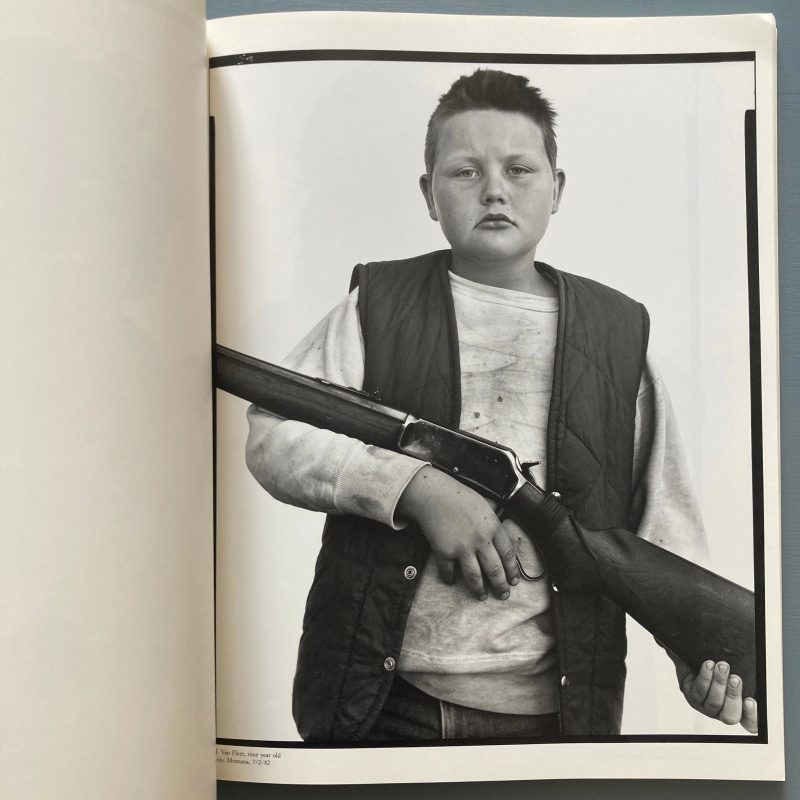

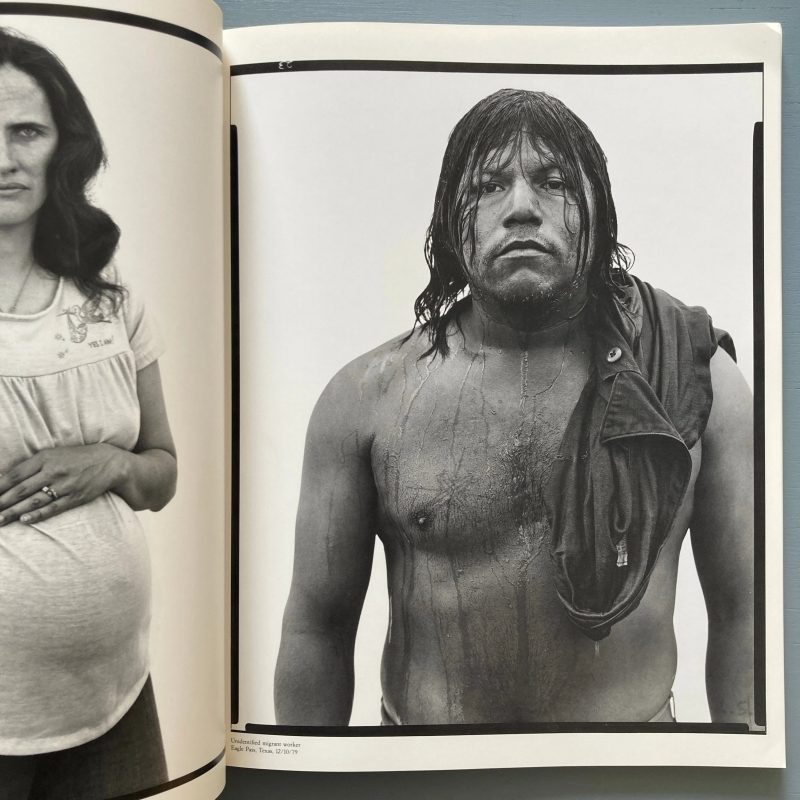

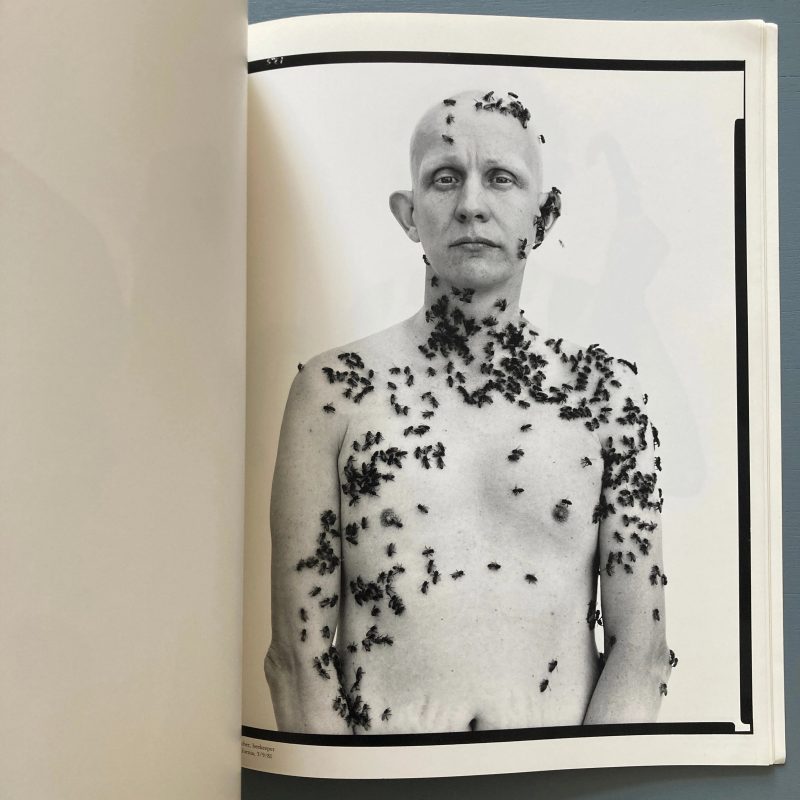

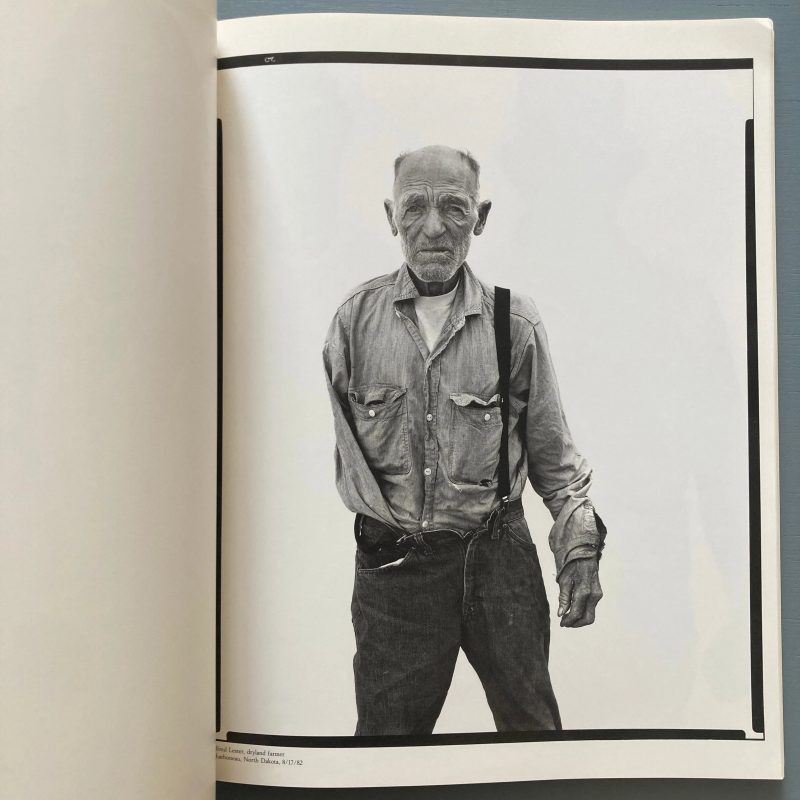

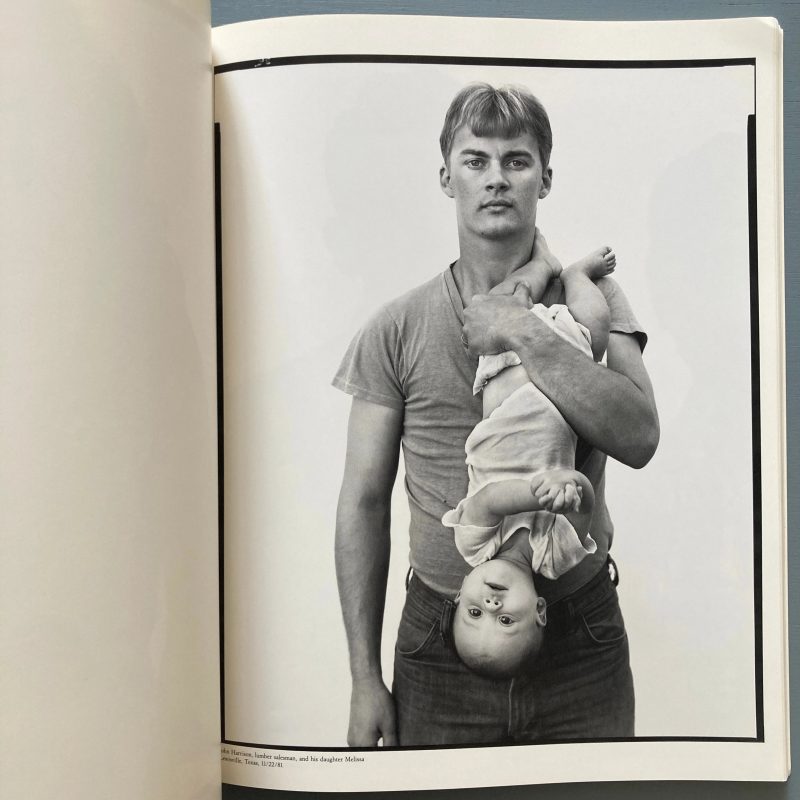

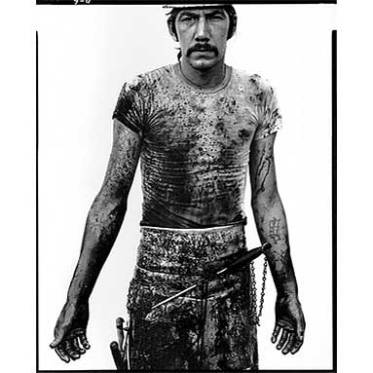

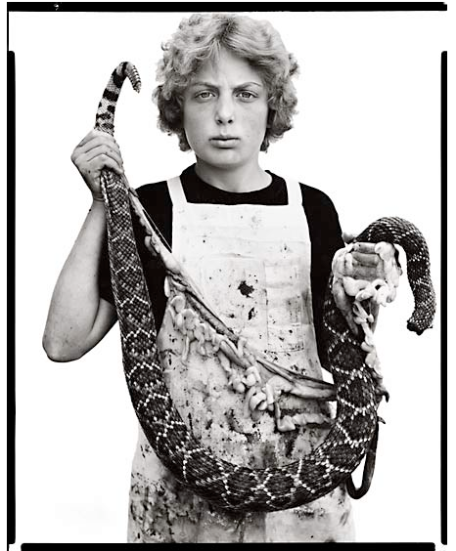

Published by Harry Abrams in 1985, this rare first edition of Richard Avedon’s In the American West documents a body of work that was originally exhibited at the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth, Texas. Avedon’s series is the result of a five-year commissioned project that saw him travel through twenty-one states, photographing ordinary people to produce a masterwork of contemporary portraiture. The publication includes a foreword by the artist and an essay by Laura Wilson. Complete with the original acetate dust jacket, this volume is far superior to the various later reprints.

Publisher: Abrams, New York

Publication Date: 1985

Contributors: Richard Avedon, Laura Wilson

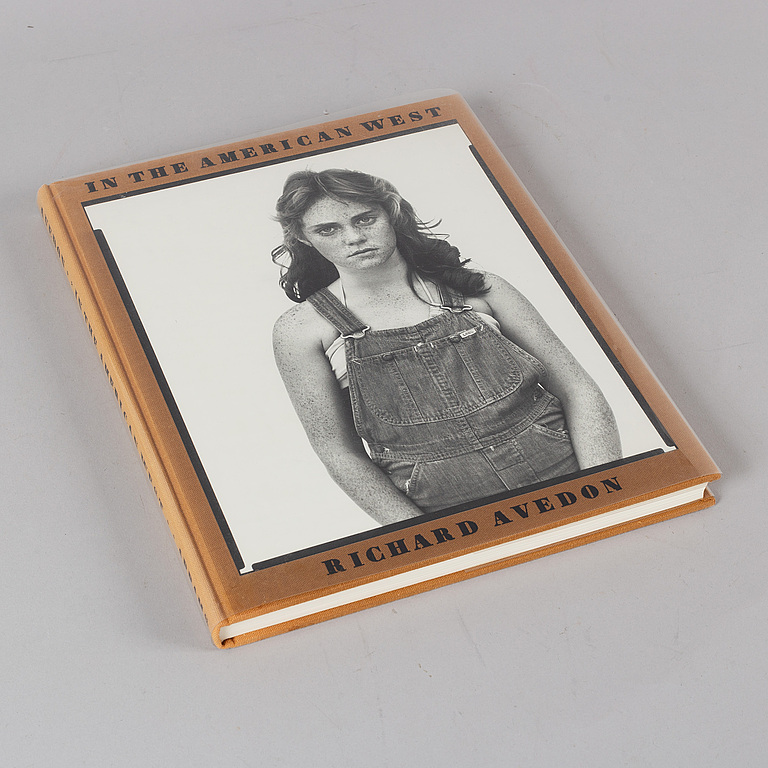

Format: Cloth hardcover in dust jacket

Dimensions: 11 1/4 × 14 1/4 inches (28.6 × 36.2 cm)

Pages: Unpaginated

Language: English

Edition: First Edition

Appraised USD$325.

Richard Avedon’s ‘Into the American West’.

Richard Avedon began his major photographic career as a fashion photographer for fashion magazine harpers bazaar, after being inspired by his parents influential careers in fashion. He has originally begun shooting identification images for the merchant marines during his two year service.

After Avedon’s marine service he was hired as a staff photographer for Harpers Bazaar, forming a close bond with the art director during his understudy from him at the ‘New School for Social Research in New York City’ after he left the Marines and he began to focus his fashion images on showing the latest fashions in real life situations and settings such as Paris’s cafes and streetcars. Avedon bought a new style to fashion photography by demanding that in his images the models show emotions and movement whereas before the norm had been for the subjects to be motionless and rather detached from their surroundings.

Avedon was already established as one of the most talented young fashion photographers in the business when in 1955 he made photography , and fashion, history by creating what is possible one of the most famous Avedon images today. He staged a fashion shoot at a circus and the image, titled ‘Dovima with Elephants’ broke the previous boundaries of fashion photography by not only having the model being shot on set but by having the model interactive with real live elephants in the image – something which had never been done before. This image features the most famous model of the time in a black Dior dress holding onto one elephant while fondly reaching out for the other. This likely led to his fame for his portrait images and his book known as ‘Into the American West’.

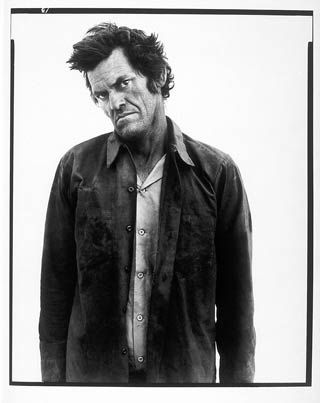

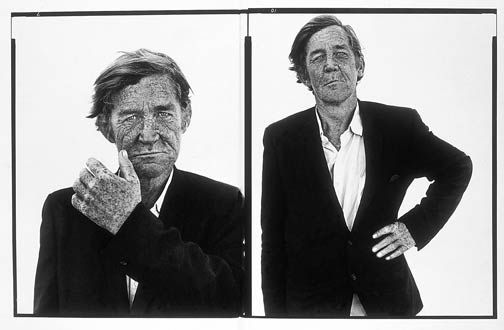

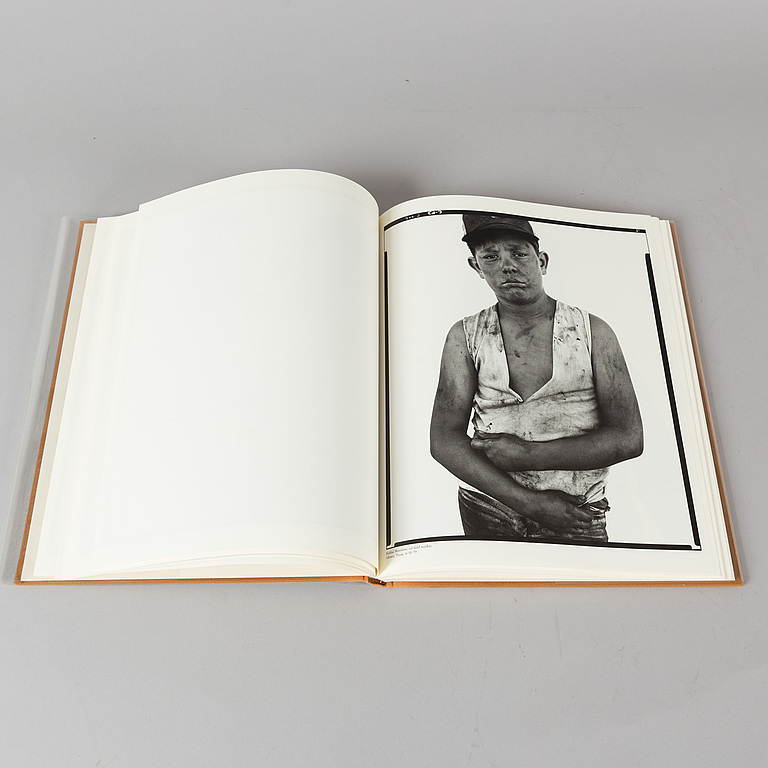

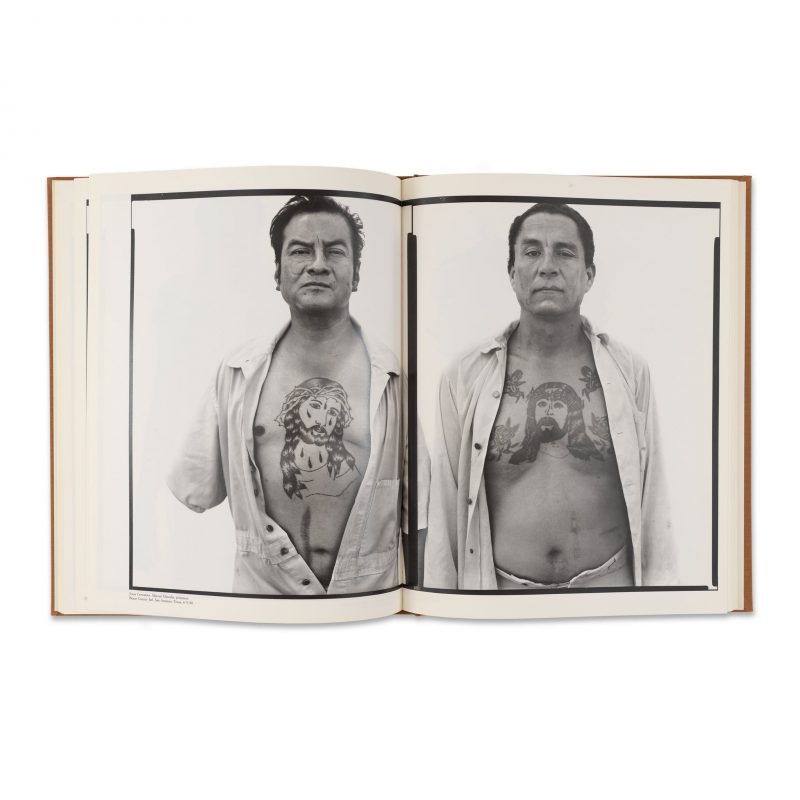

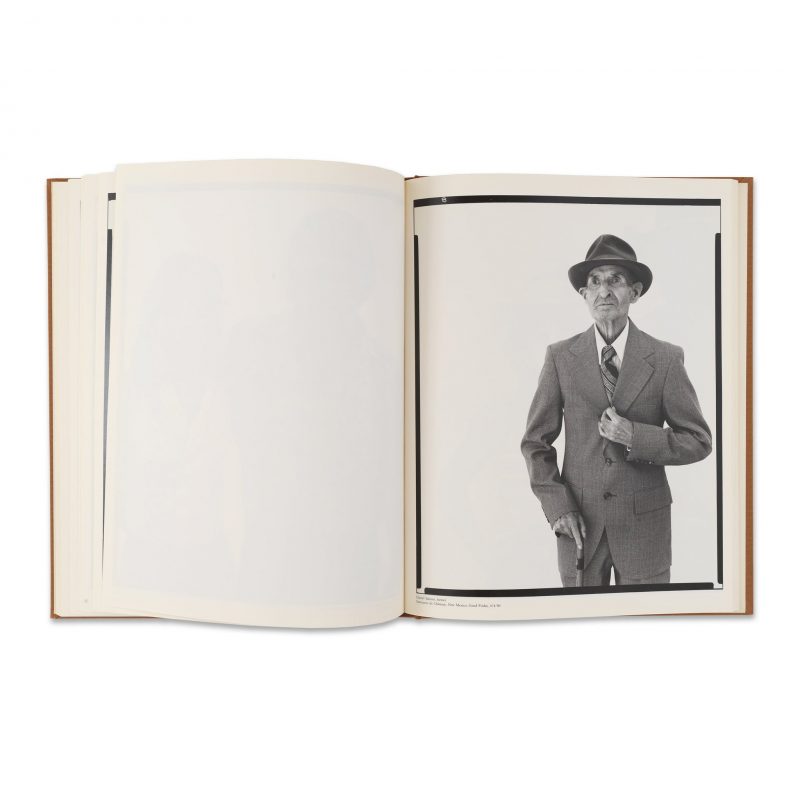

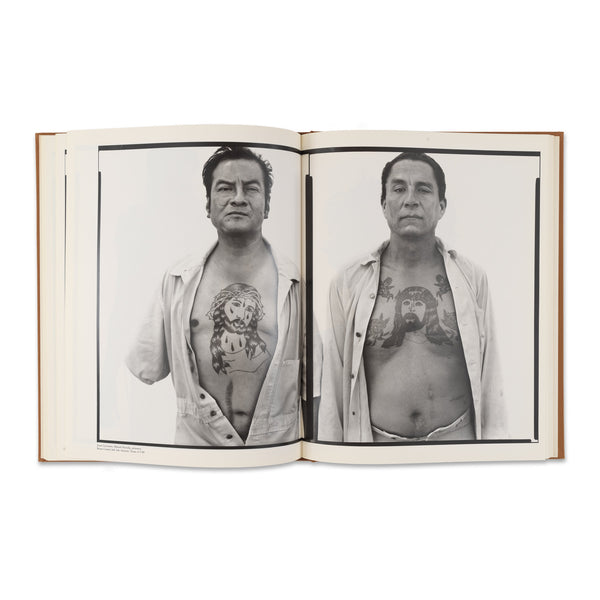

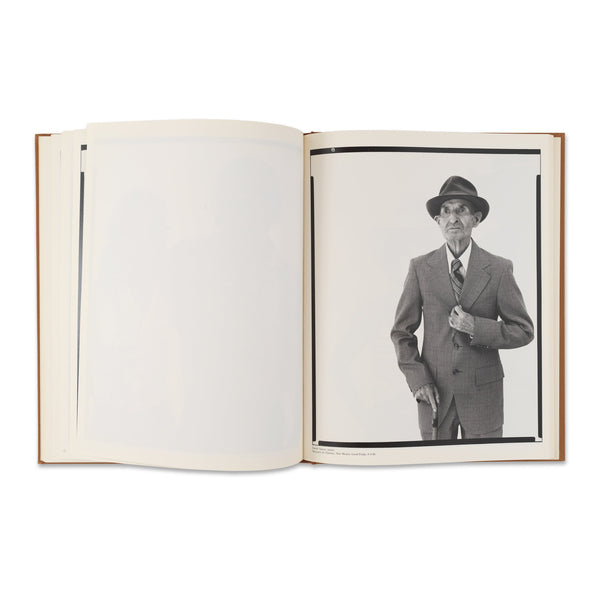

In this book Avedon attempted to capture images of a subject that showed the ‘real’ side of them and the real emotion that is within the subject rather than the ‘face’ that people put on for the camera. Avedon attempted this by asking very personal questions to the subject about themselves or their lives and often broached onto subjects that the subjects would find difficult to talk about or explain and at this point Avedon would take his image attempting to show the real emotion in a person when something like this was brought up. However Avedon seemed sceptical about the result of his own work stating , ‘Sometimes I think all y pictures are just pictures of me. My concern is…the human predicament; only what I consider the human predicament may simply be my own.’

From this we can see the difficulty of Avedon’s work and can see that he as the photographer even agreed that it is difficult to capture such emotions in people without making it almost biased or from a point of view that is your own and not the subjects. Avedon captured many of his images without the pre warning that many subjects rely on for example one sitter , Harold Rosenburg, said that Avedon “snapped the picture. Then he asked ‘Why don’t you smile?’ So I smiled but the picture was done already…” From this we can see that Avedon’s method was to capture the image before the subject had even realised that they were not smiling or posing as they might to a camera to almost cover up what they are really feeling.

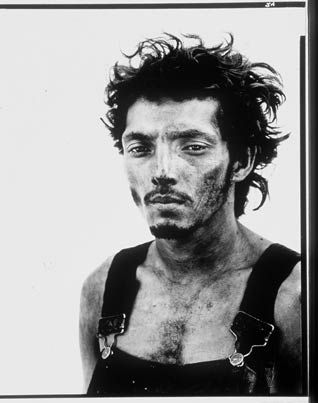

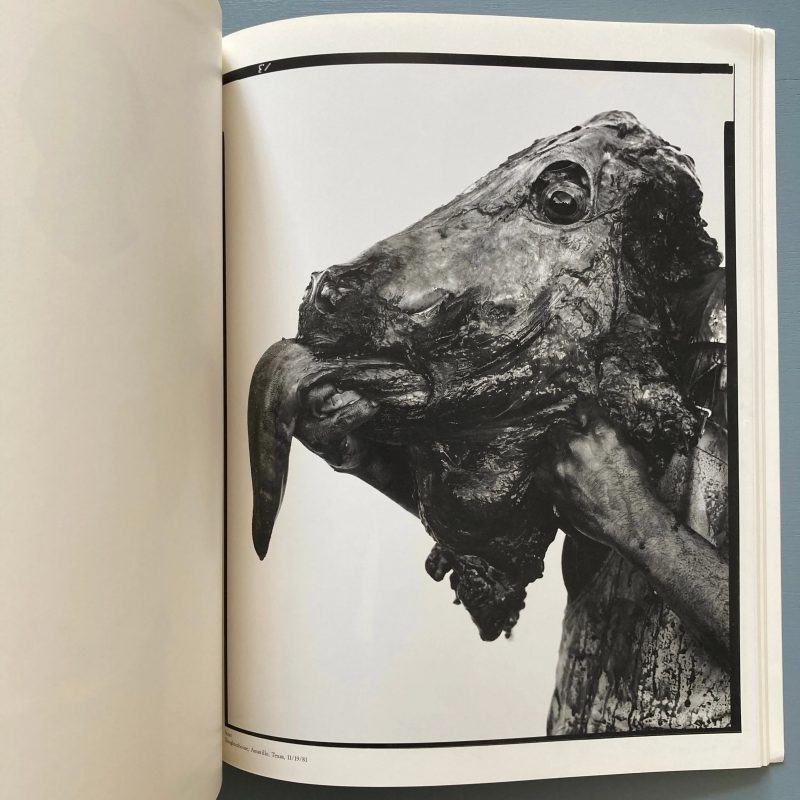

Many of Avedon’s images are glum and none of the subjects look happy about being photographed which could lead to the idea that the American West is not a happy place to be although we can agree with Avedon’s previous statement that maybe that is simply something that he thinks or is showing that is not entirely true? To further this idea of the American West not being a happy place many of the images are accompanied by dead animals or ghoulish thing such as blood and glazed eyes etc. This emphasises the idea of a dead emotionless person or area that seems to be a theme throughout this work of Avedon’s and is continued into his second book of a similar style named ‘Portraits’. Below are some exampled of this , the first being Blue Cloud Wright – a slaughterhouse worker and the second being of a young man whose job appears to be to gut snakes.

In Avedon’s book ‘Into the American West’ the foreword reads that ‘ He wanted to make portraits that bristled with emotional expressiveness without resorting to the artful backlighting and slick, patent poses of celebrity portraits by such photographers as Edward Steichen and Anton Bruehl.’ Avedon’s succeeds in this by using plain backgrounds for his subjects and a lack of fancy lighting which ensures that we are focused entirely on the expressive lack of emotion yet full of emotion that covers the subjects entire bodies and is the main focus of the images. By the lack of highlights and fancy lighting that studios would use the subject is also let free to express their inner selves without the reminder of it being a photo shoot and without the idea that they must pose and prepare themselves for the images.

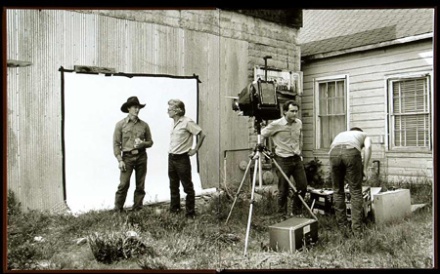

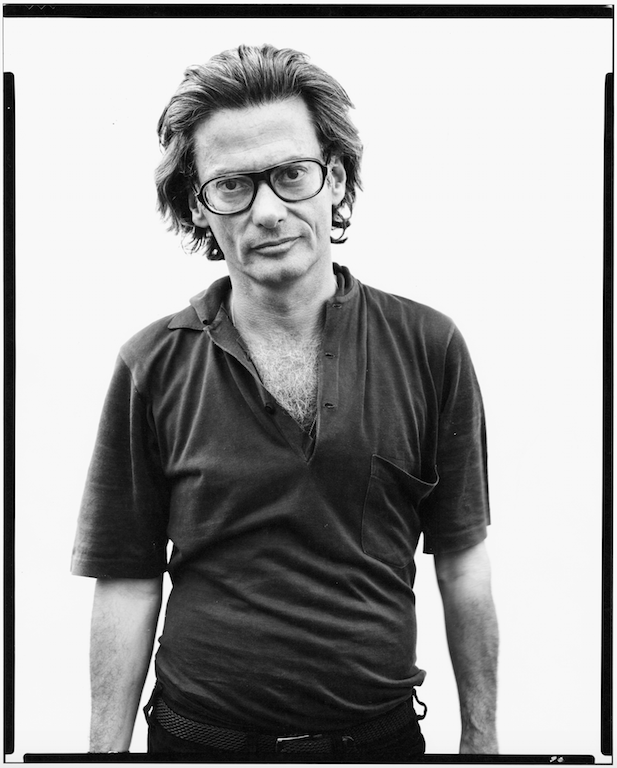

Below is an image of Richard Avedon shooting an image for ‘Into the American West’ and we can see how the subject is placed in front of a large white sheet even though they are on location and how Avedon is talking to the subject trying to bring forward that raw emotion that he seeks to see in his images.

Avedon used an 8X10 inch Deardorff view camera, allowing him to stand close to the subject as he shot them therefore being able to get into their personal space as he shot. His images were illuminated simply by the natural light reflected from the white paper and of the 752 photo sessions Avedon had with his subjects he shot 17,000 sheets of film and retouched none of the images. Along with this none of his images were cropped. Avedon had two assistants to load his camera so that he was always in control of the shoot which has a strong psychological effect on those present as highlighted by ‘Weiley’ a critic of Avedon’s book.

HISTORY

Richard Avedon (1923–2004) was born and lived in New York City. His interest in photography began at an early age, and he joined the Young Men’s Hebrew Association (YMHA) camera club when he was twelve years old. He attended DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, where he co-edited the school’s literary magazine, The Magpie, with James Baldwin. He was named Poet Laureate of New York City High Schools in 1941.

Avedon joined the armed forces in 1942 during World War II, serving as Photographer’s Mate Second Class in the U.S. Merchant Marine. As he described it, “My job was to do identity photographs. I must have taken pictures of one hundred thousand faces before it occurred to me I was becoming a photographer.”

After two years of service, he left the Merchant Marine to work as a professional photographer, initially creating fashion images and studying with art director Alexey Brodovitch at the Design Laboratory of the New School for Social Research.

At the age of twenty-two, Avedon began working as a freelance photographer, primarily for Harper’s Bazaar. Initially denied the use of a studio by the magazine, he photographed models and fashions on the streets, in nightclubs, at the circus, on the beach and at other uncommon locations, employing the endless resourcefulness and inventiveness that became a hallmark of his art. Under Brodovitch’s tutelage, he quickly became the lead photographer for Harper’s Bazaar.

From the beginning of his career, Avedon made formal portraits for publication in Theatre Arts, Life, Look, and Harper’s Bazaar magazines, among many others. He was fascinated by photography’s capacity for suggesting the personality and evoking the life of his subjects. He registered poses, attitudes, hairstyles, clothing and accessories as vital, revelatory elements of an image. He had complete confidence in the two-dimensional nature of photography, the rules of which he bent to his stylistic and narrative purposes. As he wryly said, “My photographs don’t go below the surface. I have great faith in surfaces. A good one is full of clues.”

After guest-editing the April 1965 issue of Harper’s Bazaar, Avedon quit the magazine after facing a storm of criticism over his collaboration with models of color. He joined Vogue, where he worked for more than twenty years. In 1992, Avedon became the first staff photographer at The New Yorker, where his portraiture helped redefine the aesthetic of the magazine. During this period, his fashion photography appeared almost exclusively in the French magazine Égoïste.

Throughout, Avedon ran a successful commercial studio, and is widely credited with erasing the line between “art” and “commercial” photography. His brand-defining work and long associations with Calvin Klein, Revlon, Versace, and dozens of other companies resulted in some of the best-known advertising campaigns in American history. These campaigns gave Avedon the freedom to pursue major projects in which he explored his cultural, political, and personal passions. He is known for his extended portraiture of the American Civil Rights movement, the Vietnam war and a celebrated cycle of photographs of his father, Jacob Israel Avedon. In 1976, for Rolling Stone magazine, he produced “The Family,” a collective portrait of the American power elite at the time of the country’s bicentennial election. From 1979 to 1985, he worked extensively on a commission from the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, ultimately producing the show and book In the American West.

Avedon’s first museum retrospective was held at the Smithsonian Institution in 1962. Many major museum shows followed, including two at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1978 and 2002), the Minneapolis Institute of Arts (1970), the Amon Carter Museum of American Art (1985), and the Whitney Museum of American Art (1994). His first book of photographs, Observations, with an essay by Truman Capote, was published in 1959. He continued to publish books of his works throughout his life, including Nothing Personal in 1964 (with an essay by James Baldwin), Portraits 1947–1977 (1978, with an essay by Harold Rosenberg), An Autobiography (1993), Evidence 1944–1994 (1994, with essays by Jane Livingston and Adam Gopnik), and The Sixties (1999, with interviews by Doon Arbus).

After suffering a cerebral hemorrhage while on assignment for The New Yorker, Richard Avedon died in San Antonio, Texas on October 1, 2004. He established The Richard Avedon Foundation during his lifetime.

- Market Value:

- https://www.photoeye.com/bookstore/citation/AB013