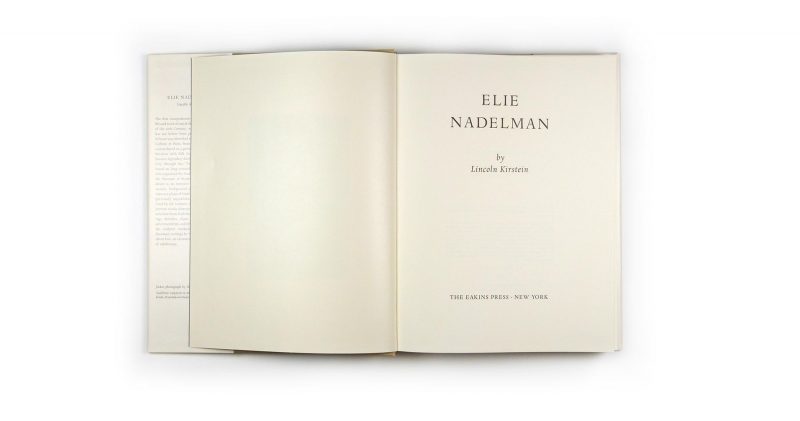

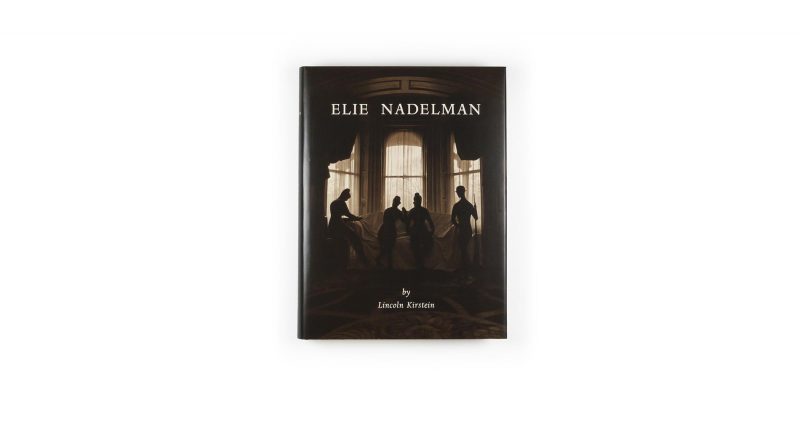

Elie Nadelman by Lincoln Kirstein, 1973

Elie Nadelman 1882-1946

DESIGN BY MARINO MARDERSTEIG; PRINTED AND BOUND BY THE STAMPERIA VALDONEGA.

362 PAGES, 215 PLATES, 12 X 9 INCHES

Lincoln Kirstein

1973

Asking USD$150.

Catalogue raisonné of the life work of Elie Nadelman with a brilliant text by Lincoln Kirstein. A masterpiece of design and printing by Martino Mardersteig and the Stamperia Valdonega, Verona, Italy.

“Extraordinary…the scope and grandeur of Nadelman’s artistic achievement fully and eloquently documented.”

–Hilton Kramer, front page, New York Times Book Review

“Definitive….author and artist illuminate each other….”

–Art in America

“Enough of dilettantism; art is not an amusement. Art is a truth which depends on the elements of the exterior world as on the emotions of the human heart.”

–Elie Nadelman

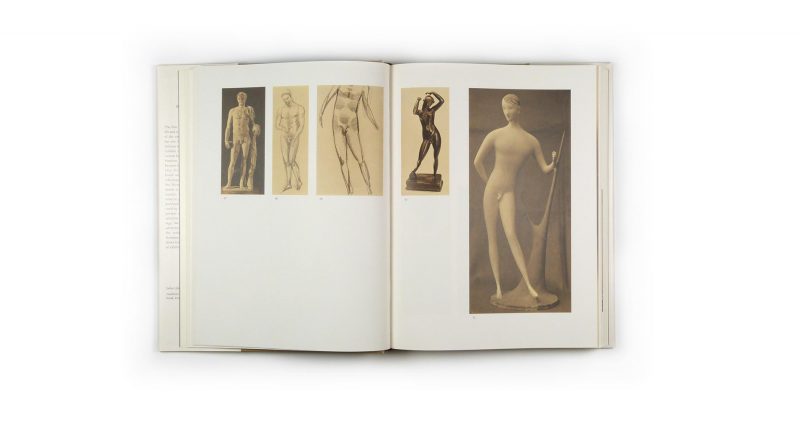

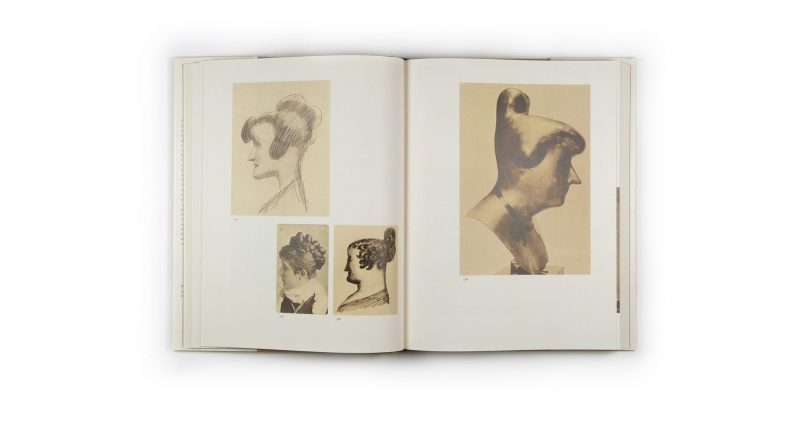

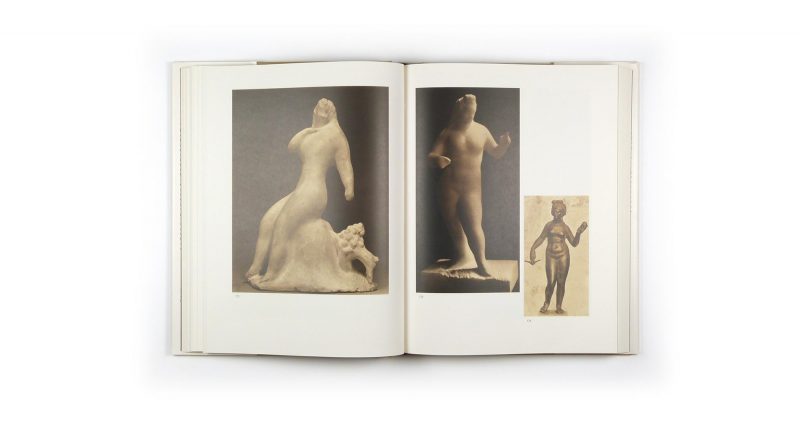

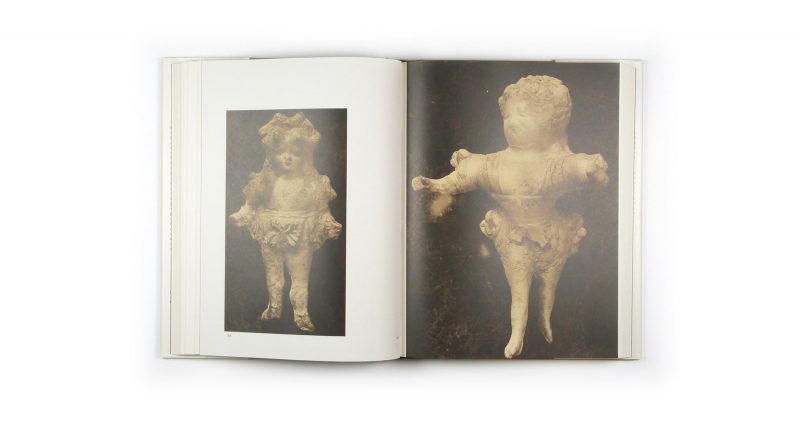

He began by echoing forms appropriate for ancient divinities; he ended by trying to project contemporary idols from dreams or nightmares of adult dolls….First, he set himself an exercise of analysing the origins and succession of Western sculpture deriving from Aegean civilization, from Pheidias through the heirs of Alexander’s artisans. In this pursuit he paralleled that of another East European, Igor Stravinsky…. Stravinsky, the grandest imitator in music, had noted that artists may never be more themselves than when they transform models.

–Lincoln Kirstein, from Elie Nadelman

BIO:

In the USA Nadelman’s work was recognised even before his arrival due to a 1913 modern art exhibition The Armory Show that the artist participated in with twelve of his drawings and one plaster sculpture (a male head). The sculptor began to be widely appreciated in the USA, many museums and galleries started purchasing his work. In Paris Nadelman became friends with André Salmon, Bela Czóbel, Amedeo Modigliani as well as with artists of Polish orgins: Leopold Gottlieb, Mela Muter, Gustaw Gwozdecki, Eugeniusz Zak, Louis Marcoussis and others. In 1919 he has married Viola Spiess Flannery, an older widow who just like the artist was passionate about fine arts. Thanks to Nadelman’s artistic and financial success the married couple could invest in properties and American folk art. They made a separate museum for their collection on their premises in Riverdale. In the 1920s Nadelman has visited Europe several times, in 1927 he finally got American citizenship. The Wallstreet crash of 1929 has deeply affected the Nadlemans. They were forced to sell their house and part of the gathered art collection. Nadelman had also less and less clients so he eventually drew back from the artistic public American life. During the World War II Nadelman was helping his family as well as his Polish and French friends. His son Jan was fighting in Europe as a soldier of the U.S. Army so he was able to pass on the news about their dear ones to his father. However news from the occupied Poland were becoming more and more tragic. Finally on 28th December 1946 in his workshop in Alderbrook, Elie Nadelman took his own life. Two years later the New York museum MoMa organised a retrospective exhibition of Nadelman’s work.

Eli Nadelman’s work was presented in several dozen exhibitions and is to be found in both private and public collections all over the world. The last exhibition of his work held in Poland took place in 2004 in National Museum in Warsaw at the department of Królikarnia.

RESEARCH:

https://whitney.org/artists/933

https://www.nyhistory.org/exhibitions/folk-art-collection-elie-and-viola-nadelman

THE art of Elie Nadelman is one the glories of modern sculpture, yet for the contemporary art public is very largely an undiscovered glory. The big double figures that preside over the promenade of the New York state Theater at Lincoln Center may be familiar to those who attend performances of the opera and the ballet, but as sculpture these works tend not to be taken seriously. Certainly, in my own experience, I have never heard so many silly, ill‐informed comments passed about any other public sculpture in New York.

There are excellent examples of Nadelman’s work in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modem Art—both in the third‐floor sculpture gallery and in the outdoor sculpture garden—but they are not the works people go to the museum specifically to see, My own impression is that they are taken—or rather, mistaken — for period pieces, amusing perhaps, undeniably well done, but without the ponderous significance of something major, something that requires thought to appreciate.

The recent publication of Lincoln’ Kirstein’s excellent critical biography, “Elie Nadeknan” (The Eakins Press, $50), has already done a great deal to reverse this mistaken attitude. Future historians of modern sculpture are unlikely, at least, to ignore Nadelman’s achievement in the face of Mr. Kirstein’s powerful statement on its behalf. But what is needed, of course, is a well selected exhibition of Nadelman’s work, which in all of its resplendent variety and elegance is simply unknown to a generation nurtured on Pop art, Minimal sculpture and the other overpublicized innovations of the last decade. The promised exhibition at the Met, origipally intended to coincide with the publication of Mr. Kirstein’s book, did not materialize. Other museum exhibitions are now said to be under discussion. Meanwhile, we are extremely. fortunate to have the exhibition of` sculpture and drawings that has now come to the Zabriskie Gallery, 29 West 57th Street. It is a very beautiful exhibition—one of the high points of the season, in my opinion—and an excellent place to begin a closer acquaintance with the workiof this unusual artist;

For Nadelman ‘is, without question, an unusual figure. His work lives on easy, affectionate terms with the traditions from which it derives—traditions ranging from the classical canons of Greek sculpture to, the “naive” conventions of American folk art—and it distills from these traditions a rich vocabulary of form perfectly capable of encompassing the mostmodern modes of feeling. There is, especially in Nadelman’s later work, a great deal that is marvelotisly witty and everf satirical, but it is never ironical about its own stylistic sources. It therefore exists at a certain distance from all those modern styles that parody the classical Past or exaggerate “primitive” prototypes in order to define a sharper emotion. In Nadelman, a connoisseur’s taste serves a vital artistic objective; is never a mere refuge for timid pieties or the sentimental evocation of a “lost” grandeur. For Nadelman, there is no lost grandeur.