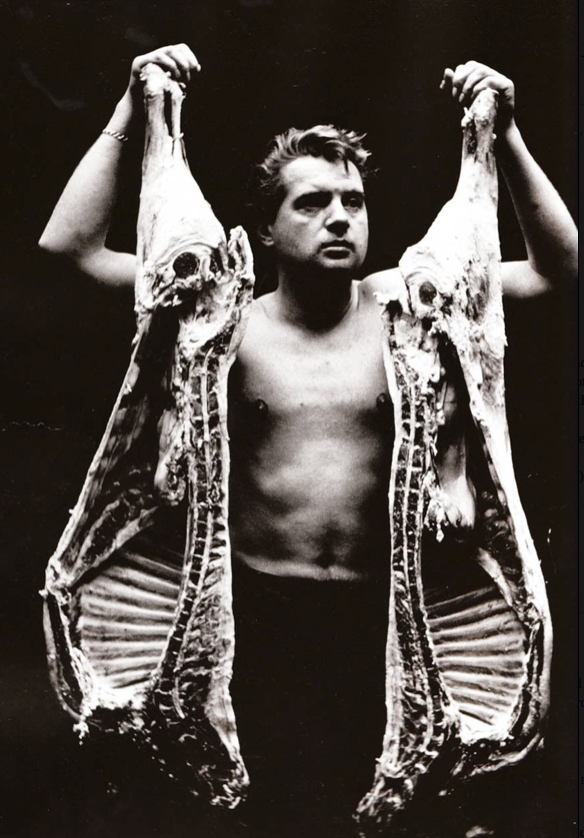

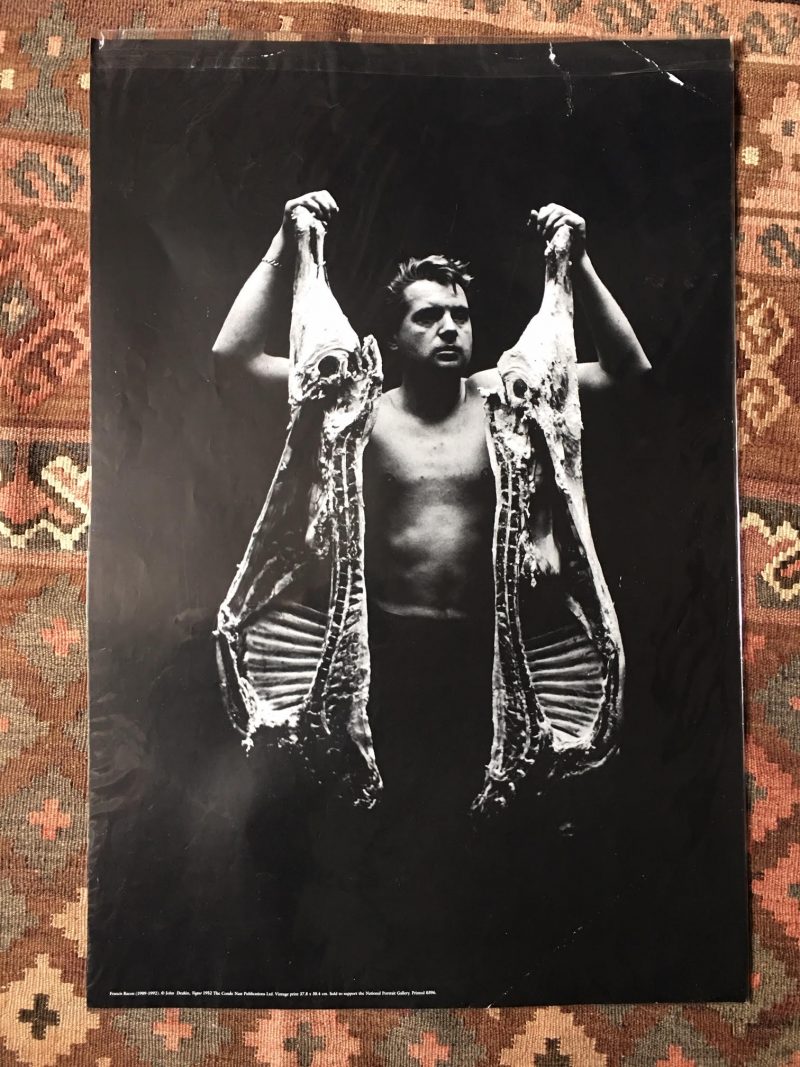

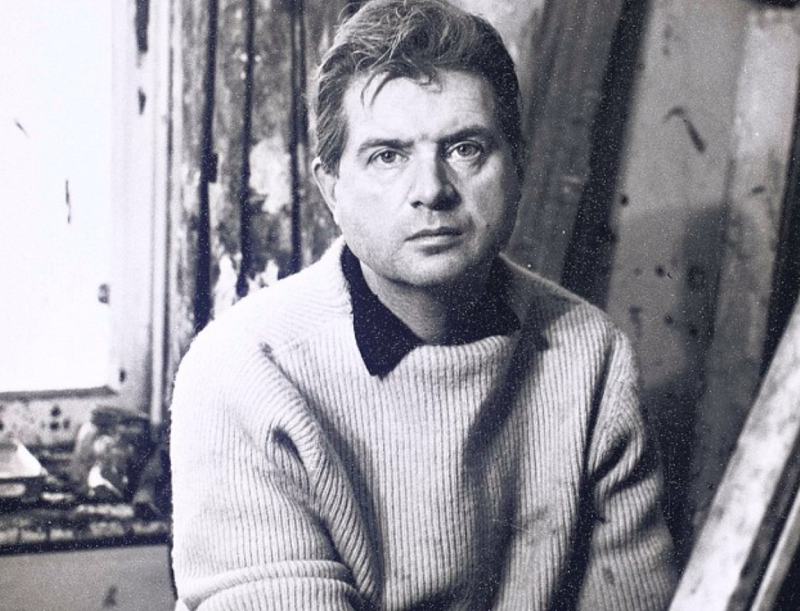

Francis Bacon (1909 – 1992) by John Deacon VOGUE 1952.

Francis Bacon (1909 – 1992) Image by John Deacon for VOGUE 1952. The Conde Nast Publications Ltd. Poster printed to support the National Portrait Gallery (Printed #0396). Poster measures 20 inches width x 30 inches height. Great condition / the creases you see at top right of poster are part of the image, not damage. Suitable for framing.

RARE Collector’s item.

USD$300.

Quote: ” The photograph of him stripped to the waist, holding a split carcass of meat, is perhaps the defining image in the Deakin galère; if it didn’t inspire Bacon’s own tortured depictions of flesh and bone it surely anticipated them”.

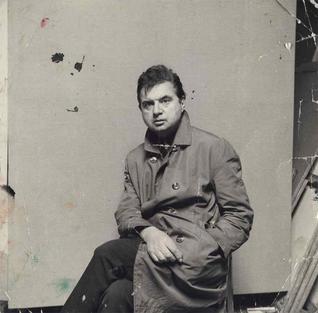

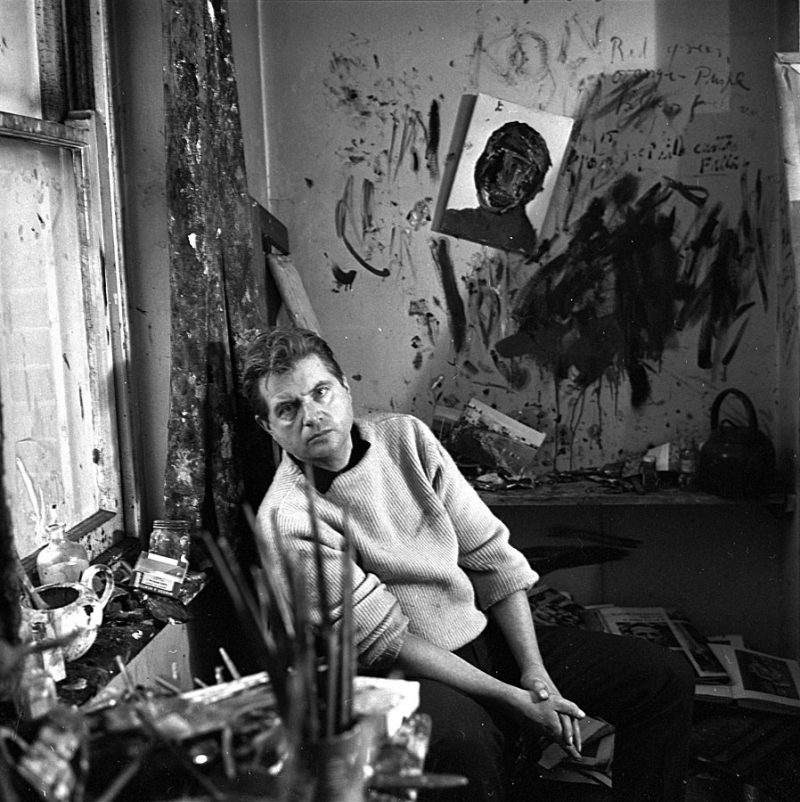

Francis Bacon (28 October 1909 – 28 April 1992) was an Irish-born British figurative painter known for his emotionally charged raw imagery and fixation on personal motifs. Best known for his depictions of popes, crucifixions and portraits of close friends, his abstracted figures are typically isolated in geometrical cages which give them vague 3D depth, set against flat, nondescript backgrounds. Bacon said that he saw images “in series”, and his work, which numbers c. 590 extant paintings along with many others he destroyed, typically focuses on a single subject for sustained periods, often in triptych or diptych formats. His output can be broadly described as sequences or variations on single motifs; including the 1930s Picasso-influenced bio-morphs and Furies, the 1940s male heads isolated in rooms or geometric structures, the 1950s screaming popes, the mid-to-late 1950s animals and lone figures, the early 1960s crucifixions, the mid to late 1960s portraits of friends, the 1970s self-portraits, and the cooler more technical 1980s paintings.

Bacon took up painting in his twenties, having drifted in the late 1920s and early 1930s as an interior decorator, bon vivant and gambler. He said that his artistic career was delayed because he spent too long looking for subject matter that could sustain his interest. His breakthrough came with the 1944 triptych Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, which sealed his reputation as a uniquely bleak chronicler of the human condition. From the mid-1960s he mainly produced portraits of friends and drinking companions, either as single or triptych panels. Following the suicide of his lover George Dyer in 1971 his art became more sombre, inward-looking and preoccupied with the passage of time and death. The climax of this later period is marked by masterpieces, including his 1982’s “Study for Self-Portrait” and Study for a Self-Portrait—Triptych, 1985–86.

Despite his bleak existentialist outlook, Bacon in person was charismatic, articulate, and well-read. A bon vivant, he spent his middle age eating, drinking and gambling in London’s Soho with like-minded friends including Lucian Freud (though the two fell out in the mid-1970s, for reasons neither ever explained), John Deakin, Muriel Belcher, Henrietta Moraes, Daniel Farson, Tom Baker, and Jeffrey Bernard.

After Dyer’s suicide he largely distanced himself from this circle, and while his social life was still active and his passion for gambling and drinking continued, he settled into a platonic and somewhat fatherly relationship with his eventual heir, John Edwards. Willem de Kooning described Bacon as “the most important painter of the disquieting human figure in the 50s of the 20th century.” He was the subject of two Tate retrospectives and a major showing in 1971 at the Grand Palais.

Francis Bacon (28 October 1909 – 28 April 1992) was an Irish-born British figurative painter known for his emotionally charged raw imagery and fixation on personal motifs. Best known for his depictions of popes, crucifixions and portraits of close friends, his abstracted figures are typically isolated in geometrical cages which give them vague 3D depth, set against flat, nondescript backgrounds. Bacon said that he saw images “in series”, and his work, which numbers c. 590 extant paintings along with many others he destroyed, typically focuses on a single subject for sustained periods, often in triptych or diptych formats. His output can be broadly described as sequences or variations on single motifs; including the 1930s Picasso-influenced bio-morphs and Furies, the 1940s male heads isolated in rooms or geometric structures, the 1950s screaming popes, the mid-to-late 1950s animals and lone figures, the early 1960s crucifixions, the mid to late 1960s portraits of friends, the 1970s self-portraits, and the cooler more technical 1980s paintings.

Bacon shows, in a period dominated by the art or abstract colored consumerism of pop art, the figure at the observation center and grasps a phenomenon that he believes irreversible: the human decay – which is not only decadence – comparing it often , with the human titanism of Renaissance and post-Renaissance painting. Of particular interest, as we shall see in the movie, it is the British painter technique that becomes an act of blatant revelation of his every thought.

He chooses or take photographs that spoils, accounts, submit to a consummation ritual cannibal; violently that prefigures, in abraded sheet, scarred and wrinkled, the development of the paint layer cakes that excess, creating a mass fleeing of shape or is fractured from cuts or lacerations. The direction is very clear, as nell’Urlo Munch: the loss of the sense, the collapse of the supernatural, the panic and the horror of existence, but at the same time, in Bacon, nostalgia and hatred against an age in which man was at the center of the Vitruvian circle.

The photograph is subjected to cuts and lacerations before becoming pictorial work matrix

Francis Bacon – Study after Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X by Velázquez (1953)

Francis Bacon – Two Figures (1953)

Francis Bacon – Three Studies for Portrait of George Dyer on light ground (1964)

Research:

Under the Influence: John Deakin, Photography and the Lure of Soho by Robin Muir – review

‘It’s surprising he didn’t choke on his own venom’ – the evil genius who captured the glory days of Soho

In the emollient climate of today’s portrait photography John Deakin’s work presents a bracing corrective. Deakin (1912-1972) photographed celebrities in his heyday, but he never cosseted or flattered them in the manner of a Mario Testino or an Annie Leibowitz. The faces of his sitters, caught in a curious hungover light, loom out at you, bemused, vulnerable, possibly guilty. He called them his “victims”, and no wonder. A portrait he took of himself in the early 1950s is revealing, his pinched features and beady gaze suggesting a spiv or a blackmailer out of a Patrick Hamilton novel. “An evil genius,” George Melly said of him, and “a vicious little drunk of such inventive malice that it’s surprising he didn’t choke on his own venom.”

The inventiveness, if not the malice, is available for inspection in Under the Influence, curator Robin Muir’s latest dip into the Deakin archive, which accompanies an exhibition currently showing at the Photographers’ Galleryin London. It is a timely book in one way, for it offers glimpses of a Soho – Deakin’s stamping ground of the late 40s and 50s – before its tragic fall into respectability. The shop-fronts, the alleyways, the graffiti on walls seize the eye as vividly as the company of artists and writers and boozers who posed for his unforgiving lens. Were he alive today one shudders to think what he would make of his beloved domain, stripped of its inimitable pungency, like a deodorised Camembert. Perhaps he would laugh – one imagines him having a smoker’s rasping cackle – given what little value he placed on sentiment. He was estranged from his family for decades, claiming to have been born in Liverpool, “near the leper colony”, an early indication of his fondness for tall tales. In fact he was born in Bebington, on the Wirral, near to where his father worked at Lever Brothers in Port Sunlight. He left school at 16, and kicked around Ireland and Spain before returning to England in the 30s; in London he found a rich American patron, Arthur Jeffress, to sponsor his fledgling career as a painter. His early work, influenced by Gauguin and Soutine, didn’t set the Thames on fire, though the Observer conceded that he was “certainly earmarked for some sort of reputation”.

Was he ever. During the war he worked for the Army Film and Photography Unit, dispatched to Cairo, Tripoli and Malta; the scenes he witnessed in the latter fed his ravenous eye for devastation and architectural ruin. He was typically facetious about his war experiences. Finding himself with the unit at El Alamein, he listened as Montgomery warned his men of the superior tank power ranged against them; the worried silence that ensued was broken by Deakin’s stage-whispered question, “Do you think we’re on the right side?”

The end of the war marks the moment when his career – and his legend – properly catches fire. Audrey Withers, editor of Vogue, was so impressed by his street photographs of Paris and Rome that she hired him as a staff photographer in 1947, and quickly regretted it. His offhand manner, his drinking, his indifference to “fashion” and his propensity for losing valuable equipment damaged an already dubious reputation. Withers eventually sacked him, complaining that he was “incapable of taking a good picture of a beautiful woman”. (Not true: Gina Lollobrigida never looked lovelier than in his mid-50s portrait of her.) In fact, he would have the honour of being fired twice by Vogue, the second time in 1954, by which time he was riding high as court portraitist and jester to the leading lights of British art. Lucian Freud, Frank Auerbach, Michael Andrews, Keith Vaughan, Eduardo Paolozzi and John Minton all went before his camera, as did writers such as Dylan Thomas, Elizabeth Smart, Louis MacNeice, Colin MacInnes and Ken Tynan. Most famous of all was his close friend Francis Bacon. The photograph of him stripped to the waist, holding a split carcass of meat, is perhaps the defining image in the Deakin galère; if it didn’t inspire Bacon’s own tortured depictions of flesh and bone it surely anticipated them.

Bacon, whose face adorns the cover of Muir’s first selection of Deakin’s photographs from 1996, played an inadvertent role in salvaging the photographer’s posthumous reputation. Deakin had pretty much drunk away the 60s, having more or less abandoned the camera in favour of painting. (There are ropey examples of his art in the current exhibition, which underline a truth: it’s not the thing you’re good at that obsesses you – it’s the thing you long to be good at.) He died of lung disease in the Old Ship hotel at Brighton in May 1972 – another Hamilton echo – and his life’s work might have gone with him were it not for the admirable foresight of his friend Bruce Bernard, Jeffrey’s brother. Bernard visited Deakin’s flat in Berwick Street, Soho, shortly after his death and retrieved from under the bed a large cache of photographs, scratched and knocked about in a way entirely typical of their late owner’s carelessness. A further tranche of Deakinia was recovered from the floor of Bacon’s chaotic studio, these smeared with paint and torn at the edges to lend them an accidental touch of bohemian squalor. Some of these prints, as Muir notes, help to plot the creative coordinates between the photographer and the painter. His shots of the model Henrietta Moraes and of Lucian Freud, for example, were later adopted by Bacon as “memory traces” for his paintings of them. He considered Deakin’s photographs to be “the best since Nadar and Julia Margaret Cameron”.

S

That verdict may be hard to challenge. However tatty some of these photographs look today, there can be no doubting Deakin’s artful handling of composition and light, or the hours he spent in his darkroom getting the grain of his prints just right. Their impact is undiminished; if anything, it has been enhanced by the passage of years. Look at his weirdly unsettling shot of Freud in 1952 and you see something nobody else caught (Deakin described him as “a strange, fox-like person”); or the heartbreaking shot of poor John Minton, face caged in his hands as if he wants to make himself disappear; or George Dyer, another suicide, nervous and dapper on Old Compton Street, two fingers of one hand, touchingly, clasped by the other. You can see that shiftiness in many of his subjects, and one longs to know how Deakin, hovering before them with his camera, created such a mood of unease. The actor Paul Scofield recalled, after an encounter: “I remember thinking uncomfortably that he didn’t like me.” It seems quite possible that Deakin didn’t like anyone very much – he just liked photographing them. This beautifully produced book testifies to a talent that still astonishes. Clapping it shut you will be struck by a powerful sense that when the glory days of Soho are remembered it will be largely through the dark-adapted eye of John Deakin.