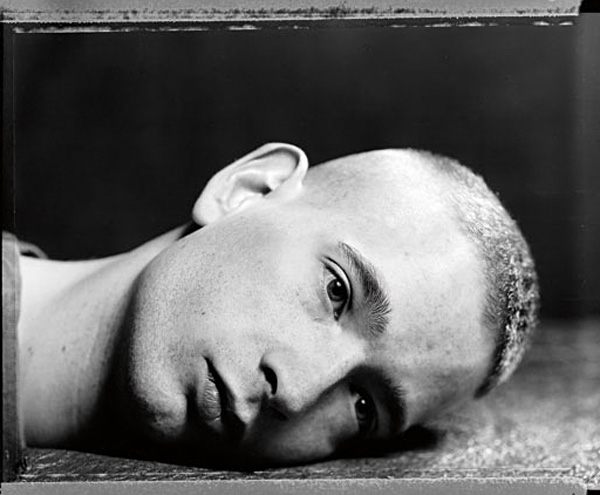

SOLD. Suzanne Opton Photograph of Soldier 2006

Suzanne Opton, Soldier Conklin: 272 days in Iraq, 2006, Pigmented inkjet print, 8 x 10 inches, Edition of 50, Signed by the artist. Purchased at an art fair in New York.

Unframed: USD$1250

SOLD.

“Opton catches soldiers both on guard and off, looking out and looking inward simultaneously, and we can only imagine what they’re thinking, what they’ve done, and what they dread. Dispensing with theatrics, Opton finds genuine drama. If these people have seen something unforgettable, so have we.” – Vince Aletti, The New Yorker, February 12, 2007

Suzanne’s work lives on the edge between documentary and conceptual. She often asks a simple performance from her subjects as a means of illustrating their circumstances.

Suzanne is the recipient multiple grants including 2009 Guggenheim Fellowship, NEA, NYFA, and Vermont Council on the Arts. Her photographs are included in the permanent collections of the Brooklyn Museum, Cleveland Museum, Dancing Bear collection, The International Center of Photography, Fotomuseum Winterthur, Library of Congress, Musee de l’Eysee, Museum of Fine Arts Houston, Nelson-Atkins Museum, and Portland Art Museum. Suzanne lives in New York and teaches at the International Center of Photography.

INFO:

https://www.lightwork.org/contact_sheet/issues/pdf/LightWork_CS136_Opton.pdf

https://time.com/27422/soldier-down-the-portraits-of-suzanne-opton/

Price reference:

https://www.artsy.net/artwork/suzanne-opton-soldier-claxton-120-days-in-afghanistan

Suzanne Opton

SUZANNE OPTON

I first became aware of Suzanne Opton’s stunning photographs of American soldiers in Contact Sheet, the long-running publication coming out of Lightwork in Syracuse. These deceptively simple portraits, accompanied by the soldier’s name and length of their deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan, show the soldiers with their heads down as if resting on the floor or across the pillow in a bed. The feelings that these pictures provoked in me ranged from empathy, anger, embarrassment, to ambivalence. These are images of soldiers unlike any I had ever seen before. Instead of vertical, armored, heroic poses, we find deliberately awkward vulnerability. Eyes, those proverbial windows to the soul, are open but difficult to assess. Are these portraits of embodied tragedy? Are they soul-less burnouts? Are they broken angels? Do they mock? Do they pay homage? That all these questions are raised yet resist answering with any certainty, speaks to the power of art in general and of these pictures specifically.

Suzanne’s determination that these portraits be made accessible to a wider public, brought her in collaboration with Light Work in Syracuse, which sponsored the first billboards, 60 miles from Fort Drum where the portraits were made. The following year CEPA Gallery presented them in Buffalo. Then in 2008 Suzanne teamed up with Curator Susan Reynolds and together they were granted NYFA sponsorship and funding from private foundations to produce a touring public art project. Billboards and subway posters brought the images to Denver, Houston, Miami, Columbus, Washington D.C. and Troy, NY. The project had secured a contract for five billboards in Saint Paul during the Republican National Convention in 2008, but the it was cancelled at the last minute because the images were deemed disrespectful. Opton replied at the time, “Far from being disrespectful, the images are vivid reminders of the hundreds of thousands of soldiers serving the country…. Since the war began, I wondered about the young men and women who chose to serve and put their lives on the line. I wondered about what they would experience at war and how they would manage their transitions to civilian life. In making each portrait I wanted to look into the face of a young person who had seen something unforgettable. And I wanted to make that a serious and intimate view, the way I would look at my own son.”

This conversation took place in Suzanne’s home in Manhattan, April 2012

MAD: You describe yourself as a self-taught photographer and I was just wondering what that means. You didn’t study photography formally…

SO: No I didn’t study it.

MAD: How did you come to it?

SO: Well when I was in college, they didn’t teach photography but there was a local photographer who would let people use his darkroom so I sort of learned that. My first job in photography was in beauty salons. It was funny. This guy who hired me had a scheme to make photographs in beauty salons, the theory being that women get their hair done and they look great so that’s the place to sell portraits.

MAD: You documented the moment of hair salon glory.

SO: He gave us a black velvet drape, and so you sort of pulled the tee shirt down and put this black velvet drape and you had some pearls, you know or something like that. A sort of formal portrait. And then the next week you’d go back and you’d show them slides on a little viewer and they’d buy them. Maybe. But I got fired because I photographed people under the dryers and things like that. So they let me go.

MAD: You were drawing outside the lines already.

SO: Perhaps. But that was my first job. And then I moved to New York and got a job in a studio as a studio assistant.

MAD: So you’re drawn to photography right away.

SO: I was, I was, but then I was a writer for a while. I did feature news pieces.

MAD: For dailies or for magazines…?

SO: For television and magazines. And then I would photograph but I always turned the light on at the wrong time….. I was distracted or whatever. So I moved and made those pictures in Vermont. I figured that if I photographed the same six people every day for a year, I’ll learn how to do it.

MAD: So those portraits on your website of the people in Vermont, that’s your first independent photographic project?

SO: That’s really where I started. I drove around and met the most interesting people who happened to be the people who never married, lived in the house they grew up in with their brother, sister, never had much ambition to have a life other than their parents. And when I rented the town hall and hung the pictures. people came out of the woodwork. You know, they hadn’t been in town for years, some of them, the real stay-at-homes. And I did interviews with them.

MAD: So that was a big event?

SO: It was a nice event.

MAD: When was that?

SO: In the mid 70s, early 70s actually. And then since I had the interviews with them too, I tried to make a book. I came to New York, I thought I’ll publish a book of these but I never managed it. I had a show of them at OK Harris but that was about it. Then I started a business making Cibachrome prints.

MAD: In the city?

SO: Yeah. I had a little darkroom on Mercer Street. Later. I worked for years as a freelance editorial photographer and taught now and then. And in the summer, I’d go out and I’d shoot.

MAD: On your website you say that you are influenced by performance. And I was wondering, do you mean performance art?

SO: Performance art, yes.

MAD: Could you elaborate on that a little bit?

SO: Well I went back to Vermont one summer I did these photographs which were called diary photographs or something where my friends and I sort of performed for the camera and it was a very diaristic kind of series sometimes presented as diptychs or triptychs.

MAD: And those performances were based on everyday life kinds of things? Like cooking dinner, getting dressed…?

SO: No they were psychological. Much more psychological or so I thought. And I used attend an improvisational dance class and I was the only one there who wasn’t a dancer. But it was interesting, that was interesting to me. I learned a lot about gesture.

MAD: Yeah, that makes sense.

SO: And doing self-portraits is like a performance for the camera.

MAD: Do you feel part of a photographic lineage? If so, is it connected to the history of photographic portraiture?

SO: When I was in Vermont, I didn’t know much, I knew the work of Diane Arbus and Walker Evans and that’s what influenced me then. And then I was interested in performance art. I don’t have a very direct lineage, I mean, I’m a portrait photographer so that’s kind of why I went to do the soldiers. But in the book Afterwards by Natalie Herschdorfer, she makes the case for a separate genre of people who step back from events, mostly events of violence and destruction and comment from a distance. I was a bit surprised to recognize myself belonging to this community she describes.

MAD: I’ll have to read that. I was thinking of Judith Joy Ross a little bit, her portraits at the Vietnam Memorial in which you sometimes don’t see the wall at all in the frame, or it’s an abstract blur in the background, nevertheless it’s almost as if all those faces were illuminated by the melancholic glow emanating off the wall. Her subjects just kind of stand there in that mournful ambiance.

SO: Those are wonderful pictures. I am a fan of her work.

MAD: Portraiture is such a basic relationship. There is a camera, there’s the photographer obviously, and there’s a person in front of the camera. It is so simple. You know it could be your driver’s license or a passport or a family snapshot. But that simple equation has produced this complex archive of human likeness. And how diverse and complex and contradictory that archive is, is not simply because humanity is diverse but also because the manner in which photographers approach the challenge of portraiture has produced such a wide spectrum of results.

SO: I think it’s very, it’s difficult to make good portraits. You stand there and you stare at the other person and you think, now what?

MAD: What do I do?

SO: And they think the same thing. What do I do? What do I do with my hands? Where do I look?

MAD: You’ve grappled with those fundamental questions over the years.

SO: Well, yes I have. I’m often very quiet when I photograph people. I sort of make a situation and hope that they’ll bring themselves to it. So there’s a bit of a collaboration. I started out doing portraits in Vermont and at the end of the work in Vermont, I became much more directional. I also did a lot of magazine portraiture. I would photograph CEOs and businessmen and I was allotted 15 minutes and…….

MAD: You had to be direct about what you wanted.

SO: Yes and I found myself being very directional. People would say to me ‘are you always this bossy?’ And in the rest of my life, maybe I have no power whatsoever. But here, you know, I can just push these guys around.

MAD: Oh, that must have been satisfying.

SO: I got to the point where I could get somebody to do just about anything. I mean, I think if you don’t have that skill as a portrait photographer, you’re a little lost. You have to have people trust you and you have to be convincing and you have to be charming and a bully, to get somebody to do something they wouldn’t otherwise do. But for me of primary importance is that the subject maintains their dignity no matter what the circumstances.

MAD: Let’s talk about your Soldier project. You must of had the idea that the image of the soldier needed to be re-imagined in some fundamental way because you did it so so radically. Is that something you saw as a necessity?

SO: I think that my work always comes from my life. Most people’s work does. If it’s strong work, there’s generally a personal connection. So when the war started, I thought about the Vietnam War and the draft, I wondered what would happen to my son if he were drafted. And how people come home from war. I wanted to see soldiers in an intimate way, the way I see my own son. And I thought, well we don’t get to see them at all. They’re always so encumbered with gear and are supposed to be representing the United States, so they have all this literal and figurative baggage, you don’t see who they are.

MAD: They become symbols rather than human beings.

SO: Symbols of heroism and soldiers of United States and all that. And then they’re killed and you see the picture of them in front of the American flag. I mean, you still don’t know who they are. So I was curious and I wanted to see for myself. I didn’t know anybody who volunteered or would volunteer, so it’s not so much that I wanted to re-do the imagery of soldiers. It’s just that I wanted to see who they were. I mean that was my reason for going there.

MAD: And one of the ways to know something is to set up this relationship through photography.

SO: Right.

MAD: Most of the soldier portraits are taken at Fort Drum?

SO: All of them are.

MAD: And I imagine that you initially had to deal with some skepticism or suspicion?

SO: I called bases all over the country. It is very difficult to understand how the military works, what powers of persuasion might be effective. Everybody blew me off, but somebody said they might let me in at Fort Drum. And then I thought after I went there, oh well I’ll go to other bases and then I realized no.

MAD: But you didn’t need to.

SO: No, in a sense it’s all the same. All I needed was in this one place.

MAD: But did you have to speak to a commanding officer and explain what you were going to do?

SO: No, I found one person who answered the phone in the public affairs office. I don’t know, I guess I had sent them an email first. And then I called them and she asked if my project was political. I said no, it’s art. She said, okay, when do you want to come? How many people do you want to photograph? And I thought, oh this is amazing, so I said, well I’ll come for 5 days, I’ll photograph 15 people a day or something, which was far too ambitious.

MAD: And then where did you set up?

SO: I said I wanted to photograph people as soon as they came back from deployment, as soon as they would allow me. People who’d just returned because I wanted to see that look – being closer to the moment, you know. I didn’t know anything about the military at the time, I soon learned that you can see that look in a soldier’s eyes thirty years later. Anyway, I asked for a studio so they gave me a room and I came with two friends, assistants and set up two 4×5 cameras, two sets of lights and we photographed everybody that they brought us. They were all volunteers.

MAD: Do you know what they were told in terms of what you were doing?

SO: I have no idea. I think it was like, “You, you’re not doing anything, go get your picture taken.” That was a volunteer. But I think that they didn’t tell them anything. I don’t know what they told them, that’s an interesting question.

MAD: Can you walk me through the relationship just as soldier first arrived. Did you talk to them?

SO: Yeah, I did those standing pictures, those were the first images I did and I did them in black and white. They’re just simple head and shoulder portraits in front of a muslin background. There were a lot of people in the room and we did one after another, so I talked to people then, but I was very careful about what I said because I didn’t want them to throw me off the base. I wanted them to put their heads down. So we talked to each other until we were comfortable and then I said, now come over here and put your head on the table. I showed them how to do it. And once they put their head down then they had to remain in that position for a time while I adjusted the camera.

MAD: And did anyone resist?

SO: I think one person in all the days I was there. One person walked in, saw what we were doing and walked out, but nobody else.

MAD: Did they sign a release? Did you show them the pictures and then they would sign?

SO: Well initially, I showed them the standing pictures and I had Polaroids of the heads down too, but I had wanted the standing pictures in black and white and the heads down in color, but I made an image of the heads down picture and I think the first one I made was soldier Birkholz, Craig Birkholz, which is a beautiful Polaroid. It’s just amazing picture and I thought this is so beautiful how can I not do them in black and white, so I did them both ways. I did a couple of Polaroids and a couple of color pictures of each and they chose the picture they wanted of the standing pictures because I wanted to give them something. At first I was sort of hiding the other pictures, the one’s with their heads down, I thought they wouldn’t be useful to them, in many cases I think maybe they didn’t understand them.

MAD: Have the soldiers seen the book?

SO. I sent a print of the standing portrait to every person I photographed and we sent a copy of the Contact Sheet to every person in the catalog. I sent copies of the book to all the Many Wars subjects and some of the Soldiers. I sent a copy to Craig Birkholz’s mother when he was killed. That was saddest thing in the world, you know that picture? He’s the first portrait in the book and the most beautiful.

MAD: He was killed in Iraq or Afghanistan?

SO: No, he was killed in the United States. He came back. Two tours, everybody else was just one tour at the time, but two tours and he came back and went back to school and got a degree in criminology, got married, became a cop as he always wanted to be and was killed answering a domestic abuse call. And the shooter was another Iraq vet.

MAD: That’s horrifying.

SO: It is horrifying. Craig Birkholz’ mother came out in support of the billboards from the very beginning and that meant so much to us. It’s incredibly sad.

MAD: Sorry to hear that. Did you do the billboard project in the Fort Drum area?

SO: Yeah. The first show was in Syracuse, and that’s where we did the first billboards. And we invited everybody I photographed. I think all 90 of them.

MAD: And did you get any reaction to the billboard project?

SO: Some people in the military wrote and either loved it or hated it. There were a number of people in the military who had strong objections. One guy said that it looks like I’ve beheaded them, and for the obvious reason, they don’t look powerful. Soldiers are supposed to be heroic and for the most part, they are heroic, but that wasn’t what I was interested in. They are also vulnerable and I wanted to show their vulnerability.

So before I went there, I figured out exactly what to do because I was scared and didn’t want to be fumbling around. I was scared that they’d ask me to leave. I was amazed that they let me come in the first place. So I planned out everything. The lights, the foreground, the background, how far they would be from the camera. All of that. I knew what I was doing. And then when it was all over, my cousin, who is a therapist said to me, oh you photographed your sister. And I thought yes, you’re right, I did. My sister was a quadriplegic for forty years and that’s how you saw her. You’d be sitting in the chair and she’d be lying in bed.

MAD: Wow.

SO: So you know, it’s interesting. I really didn’t make that connection. But when she said it, I thought, right of course,

MAD: They are unforgettable images. One of the things the pictures invoke obliquely is the idea of what the soldiers have seen. They have witnessed things we cannot know, the memories and images of which reside right behind those eyes. I think we look for some emanation or suggestion of that.

SO: Yes, I wondered if you could see that on their faces. It took so much time to arrange the camera that they were stuck, they couldn’t move, so the only thing that could move was their minds. Their mind would wander. I didn’t tell them why they were putting their heads down. I didn’t say a word. But I’m sure that they knew that. So then what would that bring up? The possibility of being shot down, close calls they’ve had, it would bring them back to their war experience.

MAD: I think of Hetherington’s ‘Sleeping Soldiers’ pictures, but those are different in the sense that they are unconscious, right, they don’t even know they’re being photographed. And we can ruminate on what the soldiers are dreaming and we can see that they are vulnerable yet relatively safe in that moment. In contrast, your soldiers are awake, and usually the eyes are open. Sometimes they are looking back at the camera and sometimes they’re not. But they are very conscious of being in that moment and their presence is, for the viewer irrefutable, yet we cannot gain access to all that is in their head.

SO: Right, and that’s also how you see your lover.

MAD: Yes!

SO: I look at somebody so close and I’ve done pictures like that. Somebody so close up with their head on the ground. I mean, you see them larger than life. You know, when you’re that close to somebody.

MAD: And it’s so intimate and yet you still have no idea who they are. What’s going on inside there?

SO: Well you’re not accustomed to being so intimate with a stranger.

MAD: Even with lovers this recognition of inaccessibility is there. You’re across the pillow from somebody and you’ve just made love with them and you look at them and think, who is that? What’s going on inside there?

SO: Right, right.

MAD: That foreign territory, that unknown territory of somebody else’s mind.

SO: Yes, but I think with a soldier, who’s not supposed to feel anything and then you take this intimate look at them. That push and pull is what interested me, I think that’s a quality the pictures have.

MAD: That is their power and their subversion. This is sort of indulgent of me, but my dad was in the Marines. He dropped out of high school and joined the Marines and was shipped off to Korea in the early 1950s. He had never left his hometown and after training at Camp Pendleton, he found himself fighting a war during the Korean winter. My dad died when I was a teenager so I never really got to know him and never got the opportunity to ask him about this, but apparently when he came back from Korea he was a different man although he never spoke about it. I guess the cliché is that he lost his innocence, but it was as if a darkness had entered him and cast this long shadow.

He had taken some photographs when he was there, some snapshots. Simple things like a peasant in a rice paddy, a water buffalo, a Korean farmer carrying a big load of kindling on his back, some of his buddies wrestling in the ground, playing soldier, men shaving each other in a field, and a Catholic mass being said in a back of a military truck. I pored over those images for years trying to see through his eyes. I was trying to find evidence of his experience of being this working class kid from Boston, plopped in the middle of a Cold War ‘police action’, which is was what it was called at the time.

SO: Yes and that little piece of your life, you never get over it. It’s like you have to grow your life around that, experience, whatever it is you see or do there.

MAD: So back to you. I really like the essay to your book by Ann Jones.

SO: She’s a terrific writer and observer.

MAD: She’s writes about the idea of the citizen soldier and how that in some ways that model is no longer active. We have an all-volunteer army and the fact that for many people, middle class people, our soldiers, or our military are strangers to us. No longer is the military a cross section of American society. It is usually poor and working class people who enlist. And I’m wondering that that was a part of your project?

SO: Yes, exactly, that’s why I was curious about them because I had no idea who they were. I don’t think any of us knew who they are. So I just, I mean it was simple to begin with. I just wanted to see who they were.

MAD: So in that sense it’s sort of like Arbus’ old thing, you know, the camera sort of like a passport to worlds we would like to explore.

SO: Absolutely, I mean, I’d never be at a military base otherwise and I wouldn’t have met those people, I wouldn’t meet them in my life in New York. For the Soldierphotographs, I only wanted the caption to state the number of days in harm’s way. How long they had been deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan. I didn’t want to include their war stories. It would’ve detracted from the looking into the face. But when I did the Many Wars interviews, I got to know people and that was very interesting.

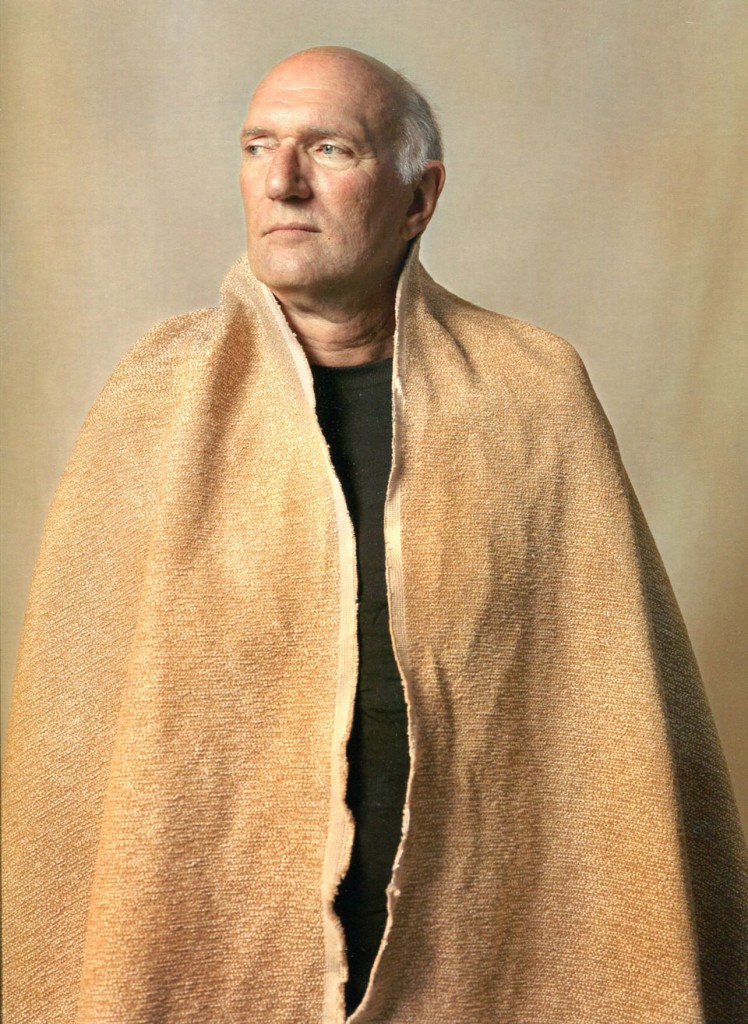

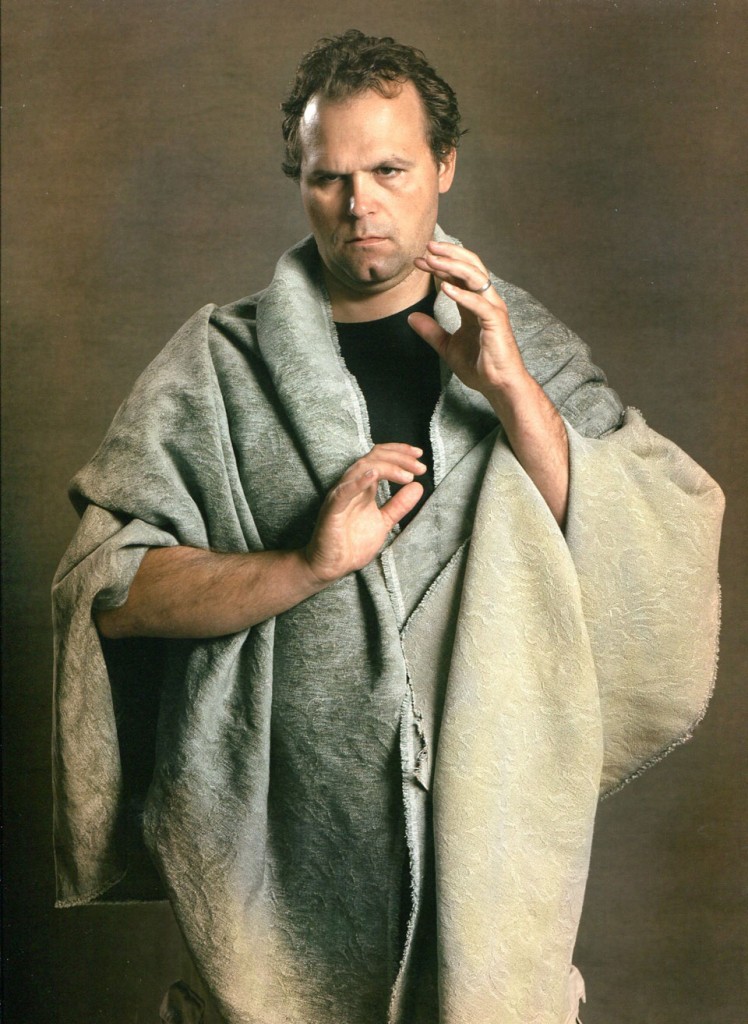

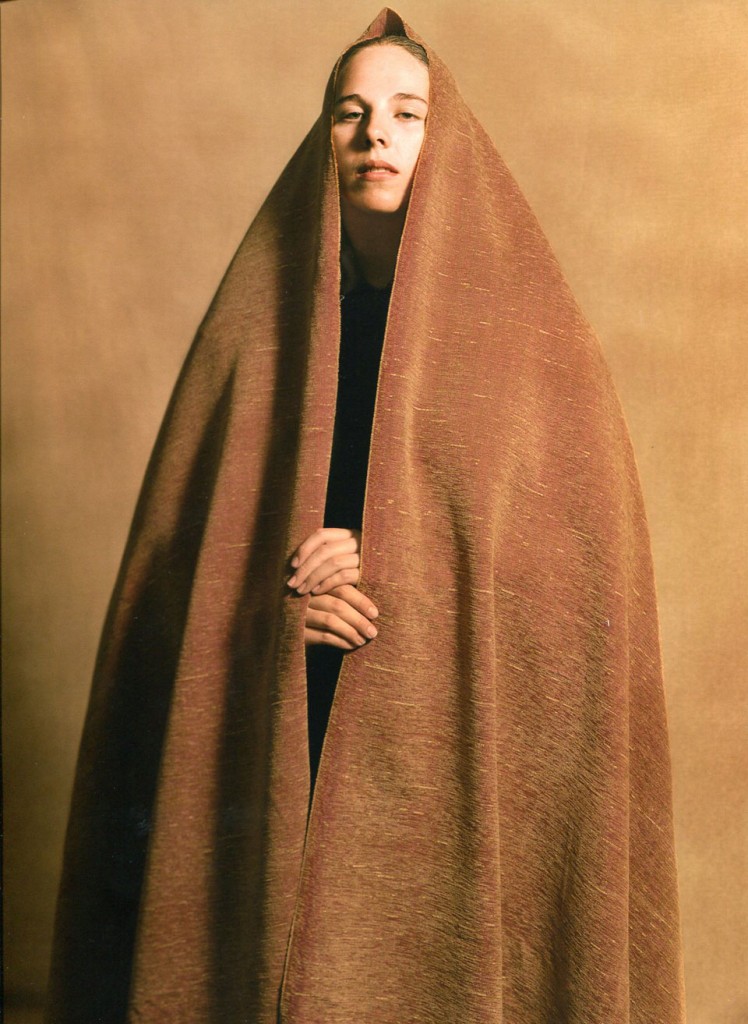

MAD: Yeah, so I wanted to ask you about that. So first of all, what’s immediately striking about the Many Wars portfolio was that all of the vets were covered. They’re blanketed, cloaked and clearly there are some religious references there. I don’t know if that was intentional, but I was thinking that they look like hermits or monks, vagrants or saints, or holy martyrs.

SO: That’s sort of my premise. And I thought with just a simple piece of fabric, they could be a homeless person or a martyr or a boy with a cape or a warrior. So it wasn’t so much religious. I mean, some of them do look religious I guess. Particularly one which oddly enough was the guy who told me he found religion there, becoming reunited with his Catholicism. But I don’t think of the other ones so much as religious. In the beginning I thought in the image of Pia Towell-Kimball, the woman with the fabric over her head, that if I photograph men with fabric over their head, I thought they would become the other. They’d be the Afghani, you know.

MAD: But did you bring that material? It wasn’t just sitting around?

SO: Oh no, I brought the fabric. The background is fabric that I brought as well. I had a lot of upholstery fabric and it’s heavy material. In the beginning, when I wanted to photograph veterans, I went to a group therapy session at the V.A. here in New York. And there were 35 Vietnam veterans and the therapist and me, which was a little intimidating. And I showed them the head photographs and they all like, ‘we don’t want to see that. We’ve seen enough death.’ They were horrified by it. It made them angry, but in the course of the hour in a half that I was with them, it provoked a heated discussion and they said, ‘you know, we were heroes, we were just boys but we were heroes and we came back and they spit on us..’

And some of them came up to me afterwards and said, ‘photograph us and make us look heroic, like we were.’ I mean, that’s sort of where I got that idea. But I don’t know why they actually thought that when they had only seen the images of soldiers with their heads down but I guess it was just the idea of recognition, which Vietnam vets felt they missed. I wanted to do these pictures and give them a certain dignity. I think that Soldiers are much more provocative than the Many Wars and I developed a deeper understanding of people who serve in the military and sympathy for them, even though I think that it is, for the most part, a dangerous gamble to join the military. But the pictures ennoble the veterans, give them back the stature that soldiers were afforded in the past.

MAD: But Its a curious paradox. I mean, there is dignity but the pictures also do not flinch at the apparent damage either. Some of that is revealed through the text, but I just think you can see it clearly in the body language and faces, that some of these soldiers are still suffering.

SO: I think that’s true. But in the past, soldiers were much more ennobled, you know, they were a bigger part of society as Ann Jones writes in her essay. They were part of our society and they were respected. And now we just respect them because we don’t want to do what we did in Vietnam. Do we really respect them or do we feel sorry for them?

MAD: Its like saying ‘bless you’ after somebody sneezes. It is expected that we thank them for their service. I don’t object to that but I think it is way to assuage guilt for the way Vietnam vets were treated. But that doesn’t guarantee any deeper understanding or empathy necessarily.

SO: Well and then there is this disconnect. You don’t want to do what we did during Vietnam but you may think that the wars are terrible and that they shouldn’t be wasting their lives there. But the soldiers themselves don’t want to think that. They’re there to protect us and I’m sure most of them believe that. And so if we denigrate their service, then that’s like saying you risked your life in vain. You don’t want to regret your life, so they have to believe that they were doing the right thing and the ‘doing the right thing’ is a very important concept in the military.

MAD: Do I have this right? For the Many Wars portfolio, you took the pictures and then interviewed later? What about that delay?

SO: Well, I don’t know, it was just circumstance, really. I wouldn’t have wanted to interview somebody before I photographed them. I want the photograph to be fresh, in terms of meeting somebody and photographing them. I don’t want to know them that well. I don’t want them to know me that well.

MAD: So you’re negotiating a relationship visually? In terms of self-presentation and the way you approach them, it’s not exactly silent, but it’s not really about verbal language.

SO: No, it’s about being seen and showing yourself. That’s what it’s about. And I don’t think that they knew what I was doing, necessarily. But I think you put this wrap on, you feel protected, safe.

MAD: So did you have to talk people into that?

SO: No, I just put it on them. I don’t generally try to talk people into things. If I had explained to the soldiers why they put their heads down, we would’ve explained it away. If you explain it, you don’t have that moment of feeling it. The feeling of it is more interesting to me, than totally understanding it intellectually And then it’d be more of a performance if they, you know, if I said I want you to be the Greek Warrior then they’d stand there like a Greek Warrior.

MAD: The stories are edited I imagine, when would you interview them?

SO: Oh sometimes a year later.

MAD: And so would you show them pictures at that point?

SO: Oh yeah I sent them pictures. there’s much more in the interviews than what you find in the book. Many of those people were in treatment for combat trauma and they were introduced to me by their therapist and the photographs were taken at the V.A. in the group therapy room, so it was a comfortable sort of umbrella for both of us. I was interested in how a person recovers from a war experience, so that was really the a crux of the interviews. I tried to edit them so that the causes and manifestations of combat trauma are in their words rather than in mine.

MAD: They’re pretty wrenching stories.

SO: The stories are very difficult. When I was preparing to give a talk about the work, somebody said to me, just tell some of the stories and I did and I thought why am I talking about this stuff? Killing and it’s all so horrible. I didn’t feel that when I was doing it, but afterwards.

MAD: So when you do give the lecture about the work, do you recite some of those texts?

SO: Very little. Maybe one or two at the most. No I talk about the process more. People can read the book if they want.

MAD: Is there is a danger of pathologizing veterans? There is that horrible stereotype of the crazy Vietnam Vet in popular culture. Obviously there are vets who adjust and move on to lead healthy lives.

SO: Yes, obviously that’s true. My feeling after meeting all these guys some of whom fought in World War II is that it doesn’t matter what war you’re in. Coming home is the same. I can’t imagine that it’s ever a smooth transition. And now we read about how soldiers drink or commit suicide or threaten, beat their wives, or they can’t hold a job or they push it all down, whatever, it doesn’t matter what war you’re in. But you are right, there is a danger in stereotyping veterans. Although the people I photographed were almost all having trouble.

I mean, this whole book is about trouble. I don’t think you can go to war and come home the same. We don’t come home the same from all kinds of events from our lives. You have children, you’re different. Your parents die, you’re different. You get married or divorced and you’re different. All those kinds of things make up our memories and how we see ourselves and become part of who we are. War is like a huge thing in a young person’s life. I mean, huger than anything. Not huger than your childhood, which you probably don’t understand at age 18 when you go to war. You may be a perfectly well adjusted happy kid, you go to war and you’re something else. There’s a blip in their timeline. That’s always interested me: how people adjust to trauma, to events, how they grow around them and how that changes them, so. That’s what I look at, but its not the whole picture certainly.