Randal Levenson (Miami, USA), ‘In Search of the Monkey Girl’ Photograph

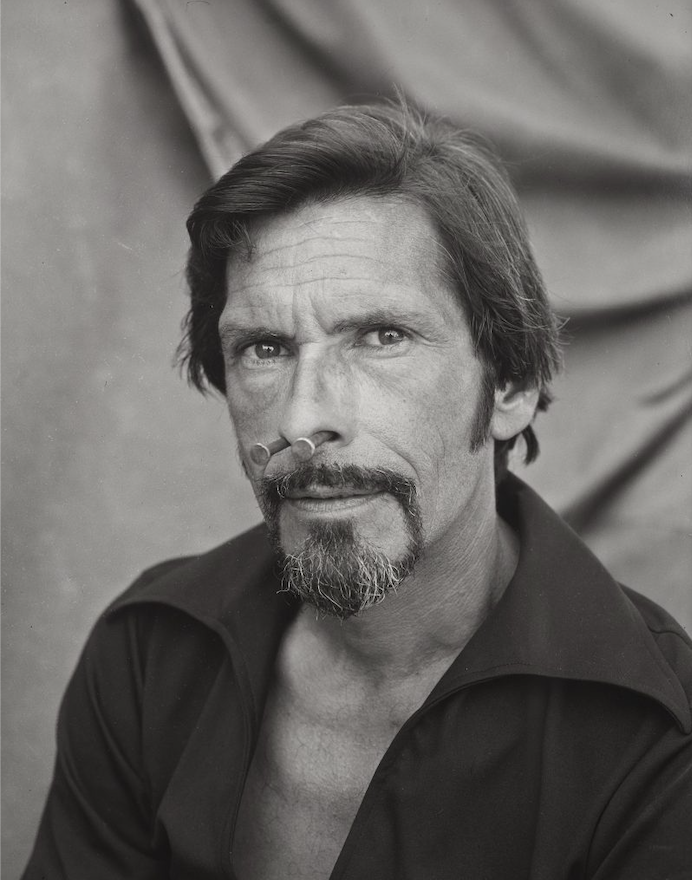

Randal Levenson (Miami, USA), In Search of the Monkey Girl, Johnny Meah, Human Blockhead. Digital Print made approx. 2014. Unsigned. Open Edition.

USD$400 / print only

We Ship Internationally / Frame cannot be shipped due to fragility of glass

BIO.

Randal Levenson | American, Born 1946

Randal Levenson was born in Wichita Falls, Texas in 1946 and developed an interest in photography during time spent in Alaska in the 1960s. He attended Brown University and studied photography at the Rhode Island School of Design.

In 1982, Aperture Press published a book of Levenson’s work, In Search of the Monkey Girl. Accompanied by text by Spalding Gray, the book documents the ten years Levenson traveled with sideshow performers capturing moving moments of camaraderie and the spectacle of life on the road. Penguin Boy, Gorilla Girl, The Man with Two Faces… These are only a few of the characters who populate Randal Levenson’s carnival of souls.

Randal Levenson’s work has been exhibited in galleries and museums throughout the United States and Canada. He has taught photography at the University of Ottawa and lectured at Harvard and Brown University.

More info:

http://www.guyberube.com/june-2014/

VICE MAGAZINE PRESS: http://www.vice.com/read/randal-levenson-in-search-of-monkey-girl

Randal Levenson: ‘In Search of the Monkey Girl’

July 3, 2014

by Adam Barbu

In Randal Levenson’s practice, insiders and outsiders become one. His series In Search of the Monkey Girl comprises photographs of enigmatic freaks, pictures of carnies, and sideshow scenes taken from his travels across North America in the 70s. His subjects included such illustrious figures as the Man with Two Faces, the World’s Smallest Mother, Penguin Boy, Willie “Popeye” Ingram, and the iconic Artoria Gibbons. In 1982, Aperture published In Search of the Monkey Girl as a book, which featured an essay by Spalding Gray titled Stories From the 1981 Tennessee State Fair.

The pictures are now on view at La Petite Mort Gallery, Ottawa, Canada, so we sat down with Levenson to talk about his days on the road, getting to know sideshow freaks, and being able to photograph who people really are inside.

VICE: What motivates your practice?

Randal Levenson: I am interested in how people work to solve or adapt to life’s problems. The camera has provided me with a means to enter environments where it might otherwise be difficult or impossible to interact.

VICE: When did you begin In Search of the Monkey Girl?

LEVENSON: In 1971, I traveled from Ottawa to visit a friend who lived in Fryeburg, Maine, at the time of the Fryeburg fair. I spent the eight days of the fair photographing both the agricultural and carnival side—that is, both the livestock arenas as well as the carnies brought in to operate the independent midway. I traveled to the next fair, the last of the season, in Topsham, Maine, living in and working out of an old Sears canvas tent I set up in the woods adjacent to the fairgrounds.

From that initial encounter with fairs, I determined to work toward a book that would document the people and places I encountered while traveling from fair to fair. I soon gravitated toward the carnies and especially the sideshow part of the business. My last was the Tennessee Sate Fair in 1981. The bulk of the work was done from 1974 to 1978, when I was able to be on the road nearly full time, thanks in part to a couple of grants.

VICE: How would you describe your experience of the circus or carnival subculture?

LEVENSON: There is no “circus” in the carnival, and carnies are generally looked down upon by circus folk. Carnies do not have much use for circus people, either. It’s a different culture entirely. In a circus, everybody is on a payroll, and most carnies except, for the roustabouts, get paid from their own independent arrangements with the main show promoter.

VICE: Another of the performers I am particularly interested in is Emmet the Turtle Man. What is his story?

LEVENSON: Emmet was a gentleman, and indeed very special—probably the most noble and most intelligent individual I encountered. At first, he was not very approachable and shrugged off the idea of a portrait. But as I got to know him over the years, he opened up and shared his story with me. We talked about economics. And where he was from. He said his situation was pretty decent—that he had some apartments in Alabama to make some money off of, but that he worked the shows to have a little extra. I am not sure, but gathered, that many of the performers collected disability as well. This is not to say it isn’t extremely tough. All the performers were pretty weathered and had been out on the road for some time.

VICE: How did the performers generally feel about their work?

LEVENSON: For the performers, being on stage did not mean opening a vein or emoting. It basically meant going up and showing yourself.

But the “non-carnie” world was their second life. I will say that they all desperately wanted to join in with the outside, “normal” society: to have a house, a family, etc. Behind the stage they were simply regular people to one another, and most of them were highly intelligent.

VICE: How would you describe your process in relation to the history of documentary photography?

LEVENSON: I work with a big camera on a tripod under a dark cloth. Sometimes it seems to me that I am “immortalizing” those who hold still for a time. I would say that Walker Evans was a major influence, as well as Ansel Adams for his technical books on darkroom technique. Also, Robert Frank for his work on the road, and Rembrandt and Goya for composition, lighting, and portraits.

VICE: For some, especially in an art-theory context, the idea of documenting “otherness” is problematic at its outset.

LEVENSON: Otherness? I photographed freaks as normal people. I found most to be fairly noble individuals. These were people I worked with on a daily basis as I learned to do “inside talking” and could live a little better on the road with a job. I could also pound sharpened car axles into the ground as stakes for the sideshow tent. That was something I learned from Willie “Popeye” Ingram.

The main tragedy in many of their lives was not sourced from their own physical afflictions, but the fact that the gene was passed on to their children and that they were similarly affected.

VICE: Most of the photographs were taken in the 70s. What does it mean to be a sideshow performer today? I can only imagine it is a shrinking circuit?

LEVENSON: I managed to spend time with the last three remaining real sideshows: Hall & Christ’s Wondercade, the Wanous family’s sideshow out of Alabama, and Whitey Sutton’s sideshow, which was being run by Elsie Sutton after Whitey died. I visit Hall and Christ and little Pete Terhune once a year or so and speak by phone once in a rare while with a couple of other performers. Many, like Emmet, I presume to be gone.

VICE: What were some of your favorite acts encountered over the years?

LEVENSON: Visitors got a lot of entertainment for their dollar, the kind you don’t get in a movie theater. Every once in a while an audience member would be so captivated to the point of fainting. It was usually but not always a woman. Sometimes they would be allowed backstage. The point is that there was always some connection made by the power of the act being performed. I remember there was particular a fire eater who had this charm. He was also desk guy that worked for IBM.

But I didn’t look at it that way. From my perspective, the act itself was not the item interest. It was not like going to a Springsteen concert. With the freaks, I learned to see what people were like on the inside rather than what they looked like on the outside. My interest in subcultures comes from a much greater question of how people solve life’s problems. And I still have that curiosity today. In a way, the camera provides me with an excuse to keep asking.

Randal Levenson’s In Search of the Monkey Girl is on view from June 6 to July 4, 2014, at La Petite Mort Gallery in Ottawa, Canada.