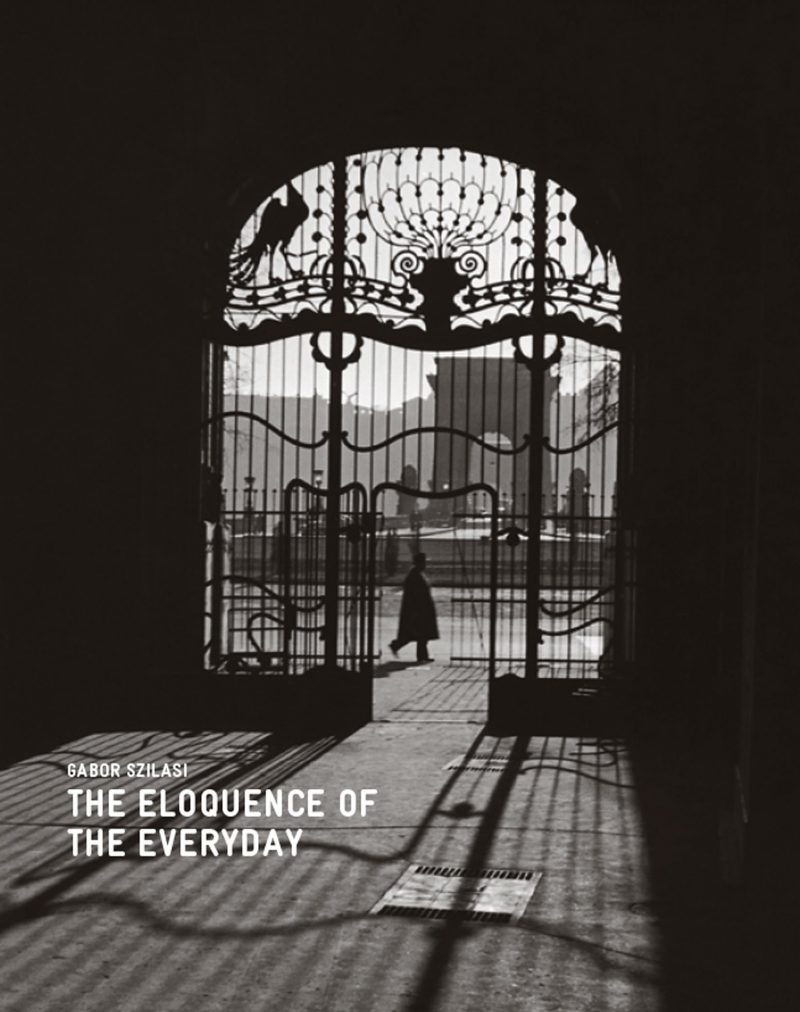

Gabor Szilasi: The Eloquence of the Everyday 2009

Gabor Szilasi: The Eloquence of the Everyday

Paperback – Illustrated, June 1, 2009

- Publisher : National Gallery of Canada (June 1 2009)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 239 pages

- Item weight : 1.29 kg

- Dimensions : 22.86 x 1.91 x 28.58 cm

Gabor Szilasi: The Eloquence of the Everyday

“Everything is constantly changing around us: what my camera captures at this moment is already of the past. That is why it is important to me to record the world as I see it today through photography. I am not interested in the past or the future: I am interested in the present. Through the photographic image, I can directly record the signs of the past and the future as they appear in this moment.”

– Gabor Szilasi, 1977

Gabor Szilasi was twenty-nine years old in 1957 when he and his father arrived in Halifax as immigrants fleeing Hungary. Two years later, he settled in Montreal, where he has lived ever since.

Szilasi had developed an interest in European pictorialist photography while still living in Budapest, but from the time of his arrival in Quebec, his work has been sustained by an unwavering belief in the documentary value of the medium. In keeping with documentary practices, his concern centres on the subject of the photograph and its clear presentation and elucidation. Szilasi’s viewpoint remains that of an outsider, one whose European perspective and sensibility have allowed him to temper formality with sympathy and to produce compelling photographs that embody a sense of profound compassion.

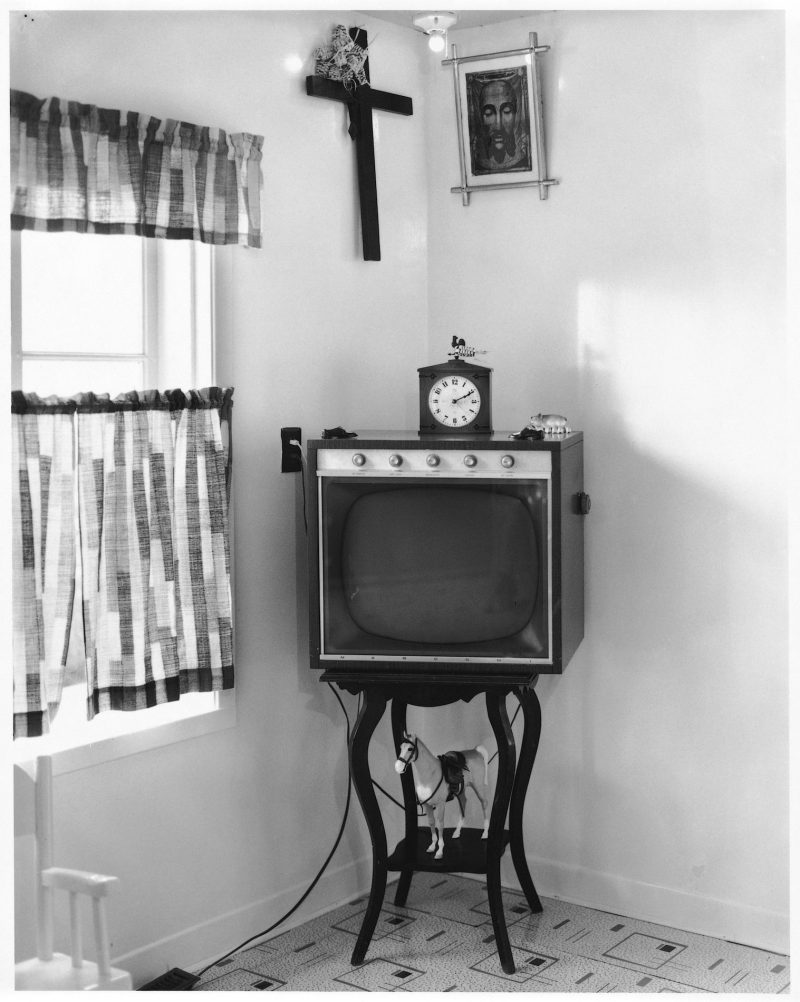

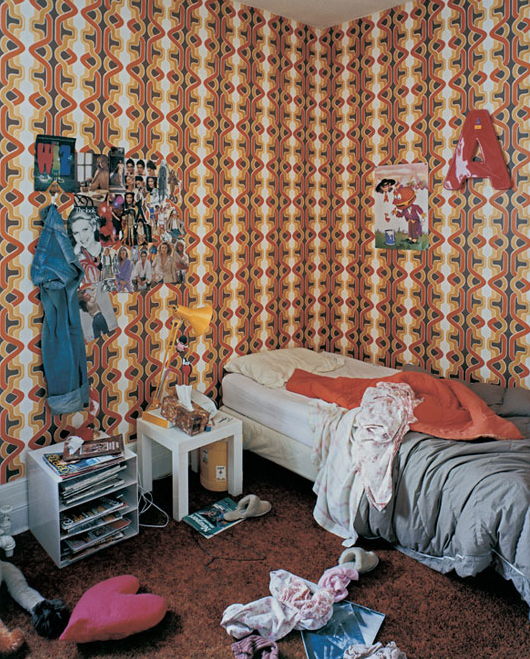

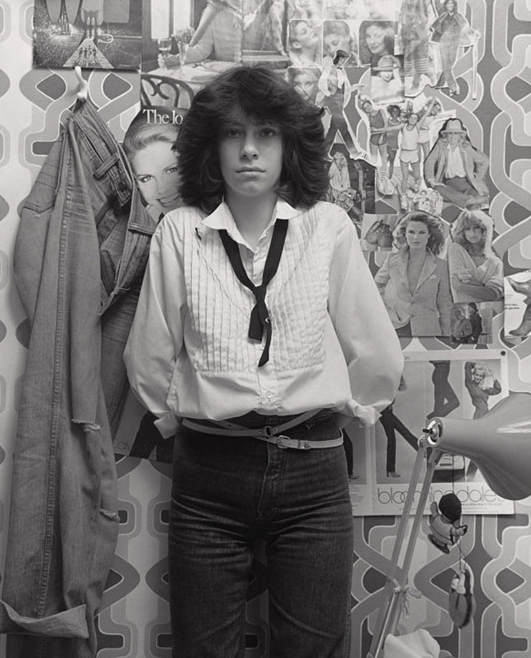

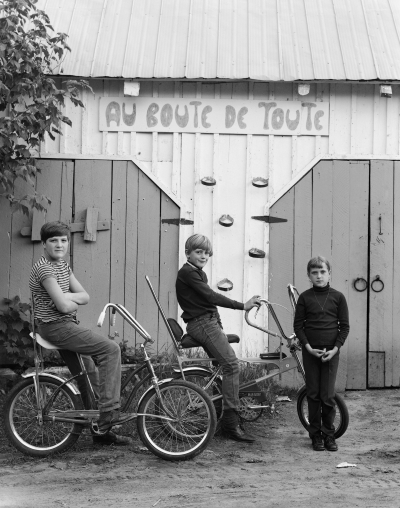

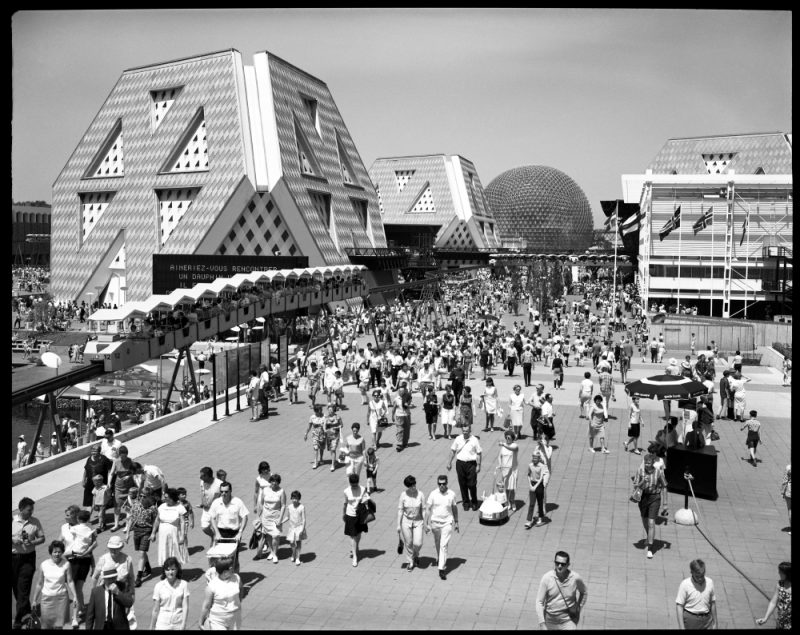

Szilasi has created remarkable images of Quebec and Europe – townscapes and cityscapes, architectural views, and environmental portraits, a genre in which the setting plays a prominent role. The cultural and historical value of the work rests not only in the eloquence of the individual images, but also in the cumulative record they provide.

This exhibition presents the photography of Gabor Szilasi, describing its evolution over five decades through an examination of the work carried out in three locations: Hungary, rural Quebec, and Montreal. Within each section, architectural, and town and city views mingle with portraits in order to reveal Szilasi’s belief in the centrality of community. The exhibition includes early images of Hungary in the 1950s, as well as those made since 1980. The photographs of rural Quebec date principally from the 1970s, while those of Montreal span the years from the late 1950s to the present.

Organized by the Musee d’art de Joliette and the National Gallery of Canada.

In addition to numerous articles, he is the author of Eugene Atget: Unknown Paris (2003; an English edition of Itineraires Parisiens, 1999), Of Battle and Beauty: Felice Beato’s Photographs of China in 1860 (1999), Gabor Szilasi: Photographs, 1954-1996 (1997), and Eadweard Muybridge and the Photographic Panorama of San Francisco, 1850-1880 (1993). He is currently engaged in a study of use and history of the photographic contact sheet.

AN INTERVIEW WITH GABOR SZILASI

Scroll down for photo gallery

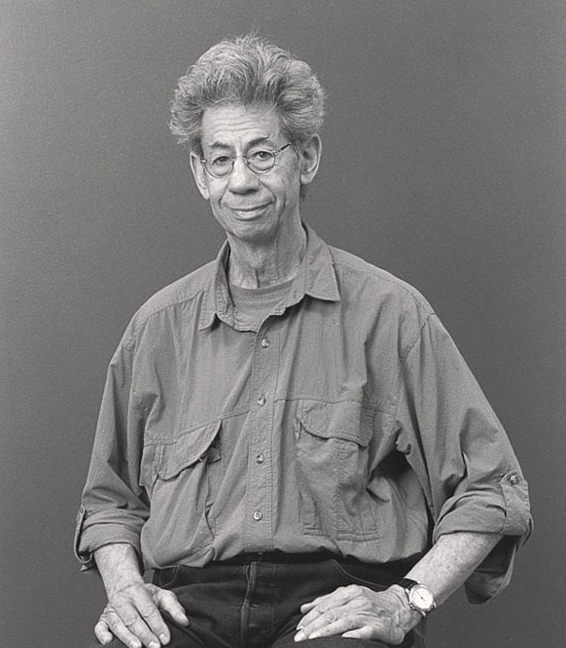

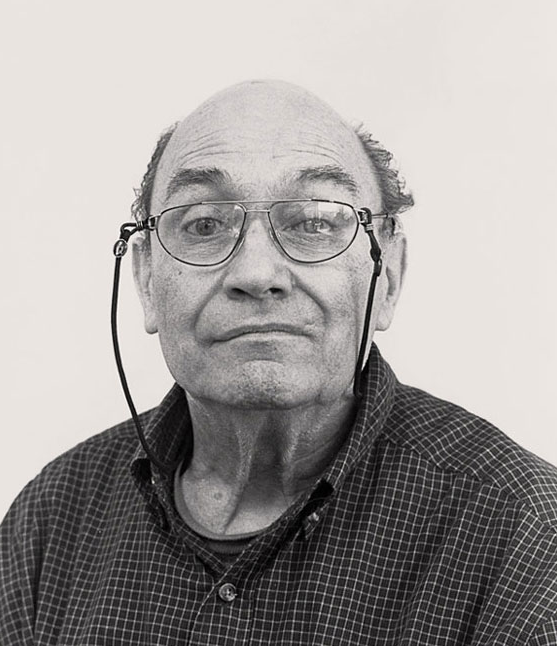

Andrea Szilasi, Gabor Szilasi in Andrea Szilasi’s studio, Montreal (April 2003, printed 2008), gelatin silver print, 22.1 x 27.8 cm (image). Collection of the artist. © Andrea Szilasi

This article first appeared in Vernissage Magazine, Vol. 12 Number 1 (Winter 2010)

Hungarian-born photographer Gabor Szilasi has lived in Montreal for half a century. Over the decades he has documented the Quebec countryside and its towns and people, artists in their homes and, more recently, urban and architectural views in his native Budapest and in Montreal. Writer Anita Lahey met the photographer in his Westmount home to talk about life as a photographer, living and working in Montreal, and his retrospective exhibition Gabor Szilasi: The Eloquence of the Everyday. The show is currently on view in Toronto at the Ryerson Image Centre until 25 August 2013.

Some of the photographs you’ve taken have become iconic. Are you ever surprised at which images people respond to?

Sometimes. One was the motorcycle [Motorcyclists at Lake Balaton, 1954]. I thought I missed that shot because the figures are going out of the picture. Their heads are chopped off. And only 10 or 12 years later did I realize that that fact makes the image: it’s very spontaneous. When I took that photograph it was right at the beginning. I didn’t know anything about photography; it was totally intuitive.

Were there also moments when sometimes you knew?

When I photographed people, I would stop if I felt the second or third photograph was the right image. But when you work with film you don’t see it right away. After you develop the negative you can discover things that you may not have seen in the moment — things in the background, or a fleeting expression.

Can you give an example in your work?

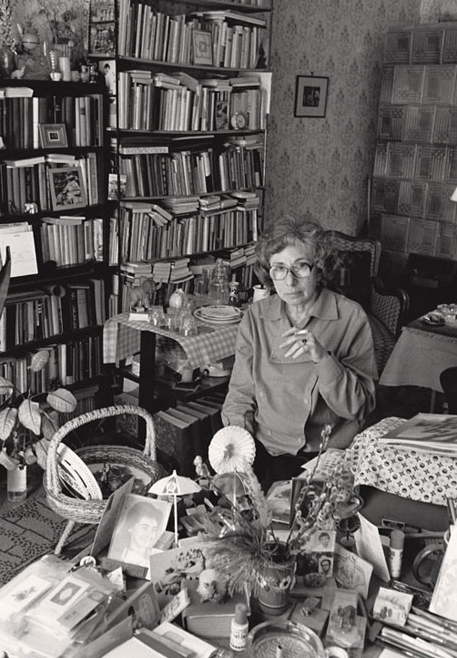

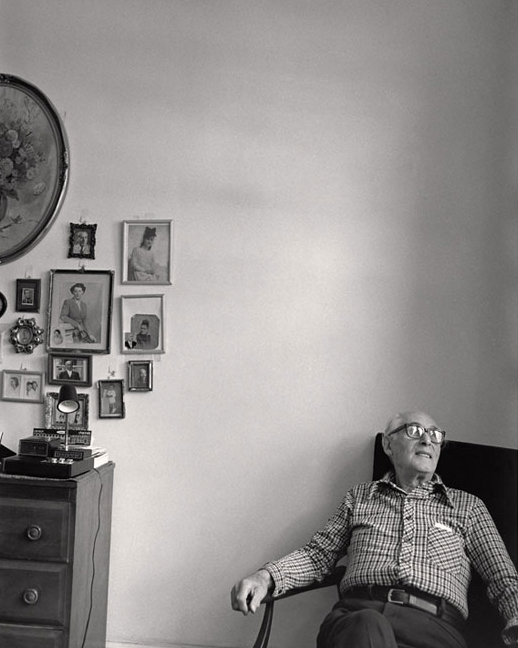

The photograph of Madame Tremblay standing in her room [Mme Alexis (Marie) Tremblay in Her Bedroom, Île aux Coudres, Charlevoix, September — October 1970] is a good example. On the chest of drawers there was a picture of her as a young girl. I used artificial light because there was no light in that room. I bounced the light off the ceiling. And it was only when I developed the negative that I noticed that the old photograph was tilted slightly towards the ceiling and washed out a little bit, so that rendered the photograph in the distance when she was young, and I thought that worked very well.

The French philosopher Roland Barthes wrote a book about photography called La Chambre Claire [Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography]. He says that in every photograph there’s what he called in Latin the studium — that is, when you study the photograph and perceive the whole image. And then there is the punctum, which is literally a small piercing object, a needle that a shoemaker would use. You look at the photograph and you notice this one little thing. When I did this series of photographs on St. Catherine Street with a 4 × 5 inch camera, someone looked at one particular photo and all this person could see was an Aston Martin DB5, the British sports car that 007 used. I didn’t even see it in the picture. [Szilasi gestures to a newspaper lying on the kitchen table]. For me, in this photograph, the watch is the thing. It’s Stevie Wonder. When you look at the photograph first you see this man with long hair, glasses, holding the harmonica, he’s a musician. But I looked at the watch; I found it strange that a performer would not remove his watch. It’s not an important object; but if it is important to him, then that in itself is interesting. So that was the punctum.

You have photographed St. Catherine Street three times over three decades. Can you talk about how you’ve seen it change?

I like St. Catherine Street. Though the buildings are mostly commercial, functional buildings, often they made an effort to introduce something decorative: fake Corinthian columns, the way they laid the brick. Some businesses were still there when I rephotographed the buildings ten years after, and others would change every few months. The facade would be redone. Some things totally disappeared; they had been demolished. I have photographs taken in the early sixties before the language laws; almost everything is in English. And that change, that’s one thing that interests me in cities. There’s an eternal flux.

When you first came to Montreal, what were your impressions?

When I arrived in 1959 we went up on the mountain and looked out and there was the Sun Life building, and Place Ville Marie, just a few skyscrapers. Now if you look down it’s totally different. But culturally, I think the basic expression — that it’s francophone — has not changed that much. Most of my artist friends are francophone, and I think it’s really important. If you really want to enjoy the culture here you must speak the language. Quebec is in a sphere of Anglophones, which is okay, that’s how it happened. But they have to make an effort to keep their own culture.

Have you thought about that a lot while you’ve been doing your work here?

Not really. I’m not very political. I’m not religious. But when I go into a store or something, I make a point to greet people in French.

You’ve talked about not being political when you’re taking photographs.

Yes. I have a certain social conscience. I’m interested in change, but I’m not initiating this change.

Do you feel ethically that, as a photographer, you should just be observing?

Actually I’m not sure. Sometimes I’ve thought maybe I should be more militant in my photography and try to initiate change, but that’s not the way I am. I observe, and it’s important for me not to exploit people. For instance, when I photographed — let’s say in the countryside or in Montreal — it happened that I went to a home where there were very poor people, but there’s poverty that can be dignified. I made sure that I didn’t exploit poverty because it can be sensational. It is really important to respect people.

How do you do that?

I ask them if they want to be photographed. If they say no, that’s fine. I want to photograph in an arena where my presence as a photographer has been established. I give them the chance to present themselves in front of the camera the way they want.

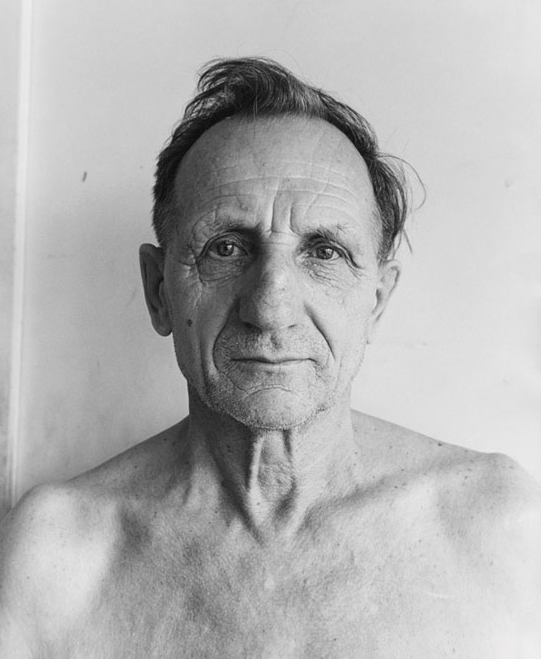

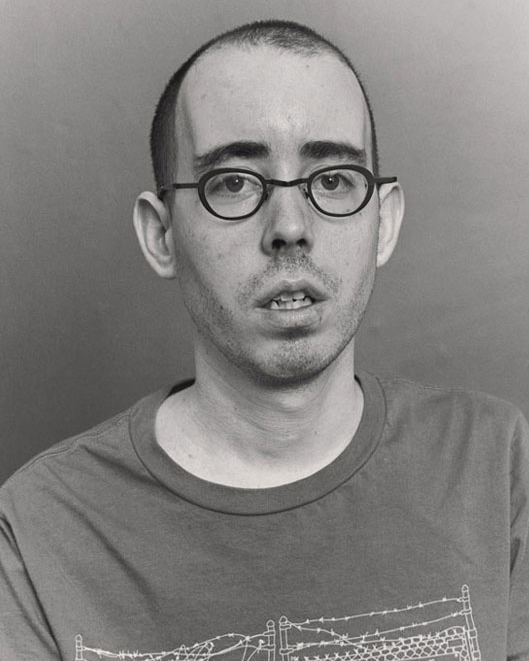

Are you able to say what draws you to photograph a particular person?

It’s partly the eyes. The “look.” And, you know, some physical facial features. Strong features. It has nothing to do with physical beauty, but inner beauty.

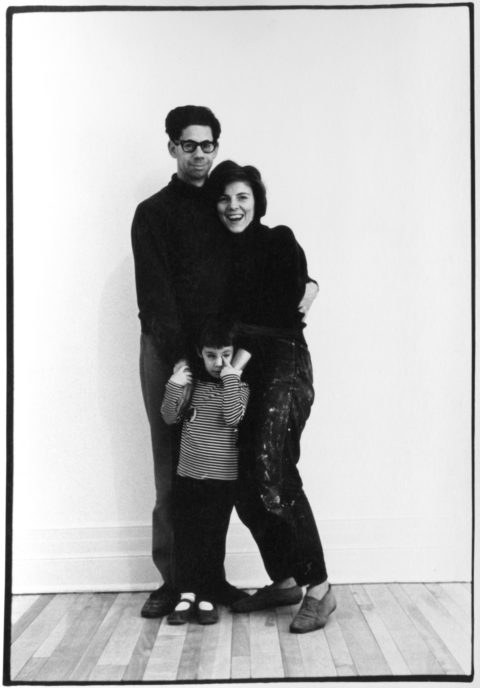

Over the years you have photographed art show openings. Why that very specific world?

I find them interesting. There are many lively, interesting people. There weren’t as many galleries as there are now, so an opening was a very special event. I am still thinking of putting together a small exhibition of these openings from the sixties and seventies.

What are you mostly working on these days?

Among other things, I’m photographing poets. I’d like to put together a small publication or edition with their writings. I even bought a digital camera which I use only for snapshots or family photos. If I want to do anything serious I still use film. I want to make sure it stays. In digital, it’s all these pixels floating, and we don’t know what’s going to happen with them.

What do you think about what’s happening in photography now?

Well, photography has opened up a lot. I think most artistic work now — even painting — is photography based. That is, based on an image, moving or still, created by a lens. Installations, and directorial photography involving elaborate settings are almost like stage directing. That’s a good thing. What I find that doesn’t really always work is big enlargements, you know, blowing them up so they’re five feet. I wouldn’t do it with my photographs. If an image is strong then it works as an 8 × 10-inch print.

You talk about trying to capture things in the present. Can you explain why you’re drawn to doing that?

Everything changes constantly. And one thing is to seek out things that are old, that are going to be demolished or disappear. I wasn’t interested in that. I am more interested in knowing that the 125th of a second — that’s how long a photograph takes — happens in the present; once the negative is exposed it is in the past. It becomes history by itself. I don’t have to work at it. There was one instance when I was photographing a house outside and the lady invited me in. It was at noon, and she offered me soup. Her husband was lying down inside, and I photographed them. I left and returned two or three weeks later. For me it’s very important to give pictures back to the people and to the community where I took the pictures. I make a point of that. If I didn’t go back, I sent them in the mail. I knocked on their door, and there was no answer. Their neighbours told me that a few days after I left the man died, and that the children took their mother to a home, so the whole thing disappeared within a few weeks. That was another instant that convinced me that things should be photographed as they are now, in the present.