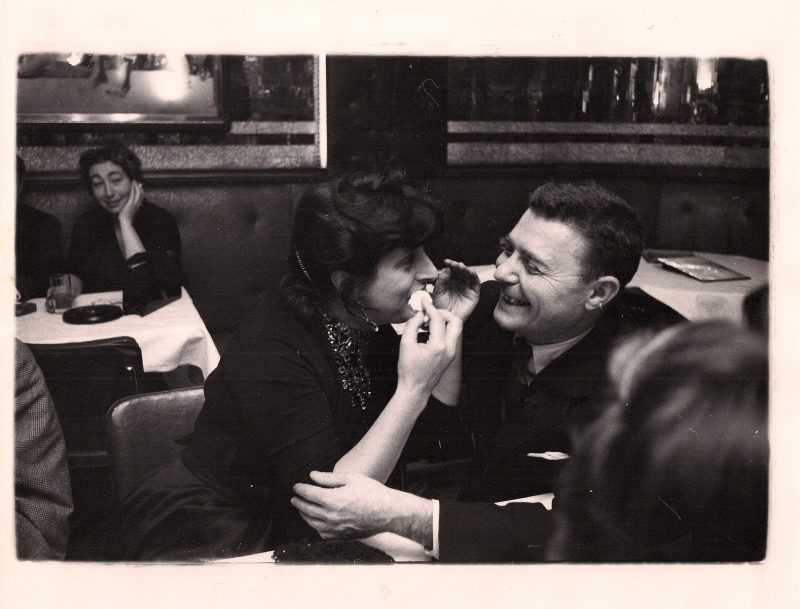

Portrait of Anna Magnani for LOOK Magazine, New York, 1950’s

Anonymous, Anna Magnani and Lover, (Italian Actress, Academy Award Winner for role in The Rose Tattoo with Burt Lancaster), Original Silver Gelatin Photograph, Stamped On Back ‘Look Magazine, New York’. Circa 1950’s. 8 x 10 inches. From a private collection / not a public image.

USD$600.

Tennessee Williams was so captivated by Anna Magnani that he wrote an entire play just for her—The Rose Tattoo. But when he asked her to play Serafina Delle Rose on Broadway, she turned him down, worried that her limited English wouldn’t do the role justice. (Maureen Stapleton stepped in instead and won the 1951 Tony.)

That didn’t stop Tennessee and Anna from forming a lifelong friendship. He once described her:

“I never saw a more beautiful woman, with such big eyes and skin like Devonshire soap.”

Anna felt at home with Tennessee, and when The Rose Tattoo was adapted for film, she finally took on the role of Serafina. Her performance was so powerful that she won the Oscar for Best Actress—though she skipped the ceremony, convinced she wouldn’t win (despite already taking home the Golden Globe, BAFTA, and critics’ awards!).

How Anna Magnani became the face of Italian neorealism

The groundbreaking Italian neorealist films of the 1940s were centred around ordinary people. No movie stars required. Yet it was a movie star that came to embody their earthy grit: the force of nature Anna Magnani.

-

This article gives away plot details of Rome, Open City

Italian neorealism was meant to be a genre populated by non-professional actors, but Anna Magnani was the exception that proved the rule. Despite her stardom, her bawdy ebullience, earthy intensity and resolute lack of glamour made her the perfect emblem for a cinematic movement centred around ordinary Italians dealing with the tough realities of life in the shadow of the Second World War. Audiences were fed up of the glossy, escapist, studio-set ‘Telefoni Bianchi’ comedies of the Mussolini era. They wanted raw, tough, gritty, real. Enter Magnani.

She’d been a mainstay of Italian cinema for much of the 1930s and early 1940s, garnering a reputation as an actor adept at comedies and dramas alike. But it wasn’t until Rome, Open City (1945) that Magnani’s career, and the Italian neorealist style, truly took flight.

Roberto Rossellini’s classic is the tale of a group of Roman anti-fascists trying to survive under Nazi occupation (an occupation that was still in place in the north of Italy during the production). In the ensemble piece, Magnani plays the pregnant fiancée of the Nazis’ prime target. On the day they’re due to marry, she’s shot to death.

Although Magnani is only in the first half of the film, she became the symbol of ordinary Italians’ bravery and determination to carry on in the direst of circumstances. Her character’s brutally rapid, unexpected killing on the streets of Rome is the most enduring image of the film, and of the movement as a whole. To be presented with such a vibrant, brave woman, and to have her death be so quick, so unsentimental… that was neorealism, in a nutshell. Rome, Open City’s resounding success at the inaugural Cannes Film Festival in 1946, where it won the Grand Prix, introduced the movement, and Magnani, to international audiences.

Rossellini and Magnani worked together again on the two-part anthology film L’amore (1948) – a more minor work, but a glowing showcase to the actor’s talent. The director promised his muse that their next collaboration would be their best yet. In the interim, however, Rossellini fell in love with Hollywood star Ingrid Bergman and gave the role in Stromboli (1950) to her instead. Magnani was devastated, and starred in Volcano, directed by William Dieterle, that same year; the films were shot simultaneously on the same group of islands, with the papers making great hay of the Magnani vs Bergman rivalry.

Still, an actor as revered as Magnani didn’t have to wait long to find another renowned creative partner. Luchino Visconti had wanted to cast Magnani in his proto-neorealist classic 1943’s Ossessione, an adaptation of James M. Cain’s novel The Postman Always Rings Twice, but she was too heavily pregnant at the time. In Bellissima (1951), he got his chance to work with her. As Maddalena, the working-class mother who’s determined to get her young daughter a role in a movie being made in Rome’s famous Cinecittà studios, Magnani is a magnetic combination of ferocity, desperation, humour and vulnerability; her resolve to succeed in the face of insurmountable odds again representative of a populace struggling to make something of their lives from the ashes of the Second World War. Bellissima has also been read as a searing indictment of the Italian film industry, willing to use any artificial measure to retain the appearance of realism, but Visconti denied this. For him, “My whole subject was Magnani.”

The golden age of Italian neorealism was a brief one. Although it’s difficult to fit the era squarely in a temporal box, 1952’s Umberto D is often considered to be the last major work of the movement. Though there’d be a scattering of films afterwards that evolved the neorealist aesthetic – including Rossellini’s Journey to Italy, Federico Fellini’s La strada (both 1954) and Vittorio De Sica’s Two Women (1960) – over the course of the 1950s, its prevalence in Italian cinema dwindled.

During this period, Magnani made several films in Hollywood, all opposite leading men known for their power and intensity – 1955’s The Rose Tattoo with Burt Lancaster, 1957’s Wild Is the Wind with Anthony Quinn, and 1960’s The Fugitive Kind with Marlon Brando. Tennessee Williams wrote the role in The Rose Tattoo specifically for Magnani, with whom he’d become good friends – though self-consciousness about her English stopped her from accepting the part on Broadway in 1951, her performance in the 1955 film was received rapturously, and garnered her an Oscar (she’d also be nominated for Wild Is the Wind).

Magnani continued to make Italian films during her stint in Hollywood, and after an unhappy shoot on The Fugitive Kind she decided to refocus all of her energies back home.

Her last major performance was as the titular character in Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Mamma Roma (1962) – a former sex worker intent on giving her teenage son, from whom she’s been estranged, a better life than she’s had. With its focus on the poor, and a largely non-professional supporting cast, Mamma Roma was Pasolini’s homage to neorealism, which had been out of fashion for a decade by the time of its release. Perhaps due in part to that perceived outmodedness, it did poorly at the box office and didn’t fare as well in its eventual release in America as many of her other films. Still, in the years since then, its reputation has grown exponentially, with it now being regarded as a worthy requiem for that groundbreaking earlier period in Italian cinema, and Magnani’s tempest of a lead performance a fittingly dynamic capper to her relationship with it.

Besides Magnani being the biggest star of a style of cinema not meant to have such things, the other great irony of her affiliation with neorealism was how much she wearied of her position within it. The year after Mamma Roma was released, long before the critical re-evaluation, she was quoted as saying, “I’m bored stiff with these everlasting parts as a hysterical, loud, working-class woman.” Magnani had spent over a decade before Rome, Open City playing a variety of roles, and yet after her barnstorming turn in the Rossellini film, she rarely got to explore the vast reaches of her range. For an actor of such dynamism, her frustration is understandable.

But however she may have personally felt about the roles she played, Magnani never let any dissatisfaction show in her performances, which remain remarkable for their vividness, power and unvarnished displays of complex emotion.

“When I die, when people think of me, they must know Magnani never lied to them. They must be sure that Magnani never betrayed them, and that Magnani never betrayed herself.” That stubborn, unyielding honesty was the core of neorealism, and – of course – the core of Anna Magnani.