SOLD. Jean-Michel Basquiat: ‘Now’s the Time’ 2015 Exhibition Catalogue

- Publisher : Prestel (Feb. 20 2015)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 228 pages

- Item weight : 1.53 kg

- Dimensions : 26.67 x 3.18 x 29.85 cm

- Essay: Dieter Buchart

- Designed by Gilbert Li

Offered at $125

SOLD.

- Notice please: catalogue has a handwritten dedication as a gift, in black marker, on intro page.

Reviews:

JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT: NOW’S THE TIME

Dieter Buchhart, Art Gallery of Ontario/Prestel, 228 pp.

Jean-Michel Basquiat confronted issues of racism, class struggle and social hypocrisy very specific to New York in the 1980s, a scene that exists now only in the memories of a few, but his work still resonates in crystal-clear tones. The essayists in this AGO catalogue attempt to explain why. In his glib crowning of Basquiat as a “punk sage” and “Tesla coil with dreadlocks,” Glenn O’Brien blunders a chance to portray his friend as anything other than the mythological figure built up by the indefatigable cult of his celebrity. Thankfully, curator Dieter Buchhart and University of Toronto professor Christian Campbell probe deeper. Buchhart acknowledges the artist’s prescient anticipation of the copy-paste sampling style of the Internet generation, revealing why his approach still feels so inspiring and aesthetically contemporary, and Campbell explores what Basquiat’s work could mean to multicultural Canadians today, asking, “What is the relationship between Irony of a Negro Policeman and the overpolicing of black people in Toronto?” Will this exhibition aid in ending Canada’s polite silence on race, or, “Will it just stay the SAMO SAMO?” – Canadian Art

—The Boston Globe

“Now’s the Time is a stunning collection that demonstrates the power and depth of Basquiat’s work and why it will continue to endure.” —The Boston Globe

“An expansive survey produced in conjunction with the Art Gallery of Ontario, and the first major retrospective of Basquiat’s work in Canada. . . . The five essays that conclude the volume are bookended by striking photographic portraits of the artist. . . . This collection illustrates how the work retains a sense of the ‘now,’ their relevance deriving not only from the subject matter but also from the urgency contained within Basquiat’s visual aesthetic.” —The New York Times Sunday Book Review

The Catalogue:

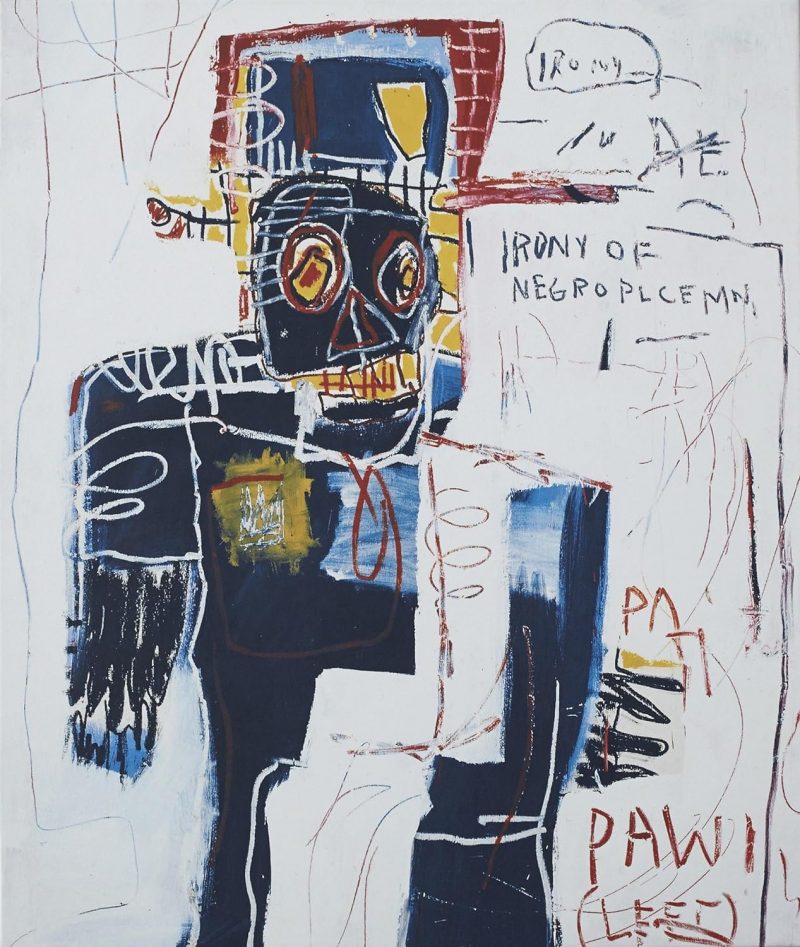

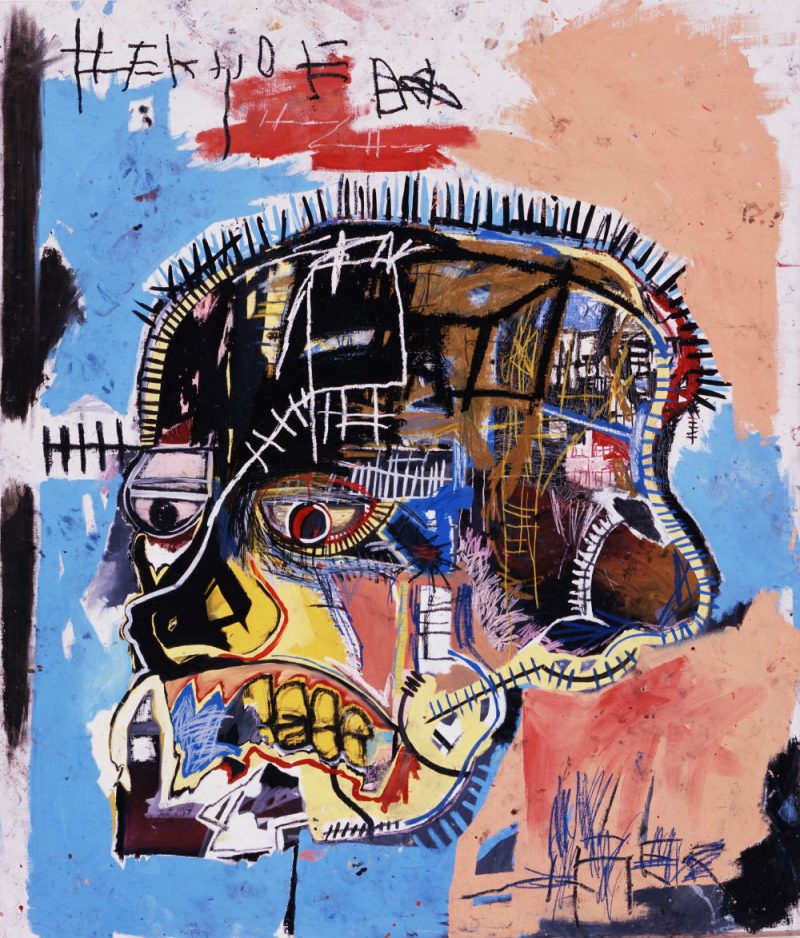

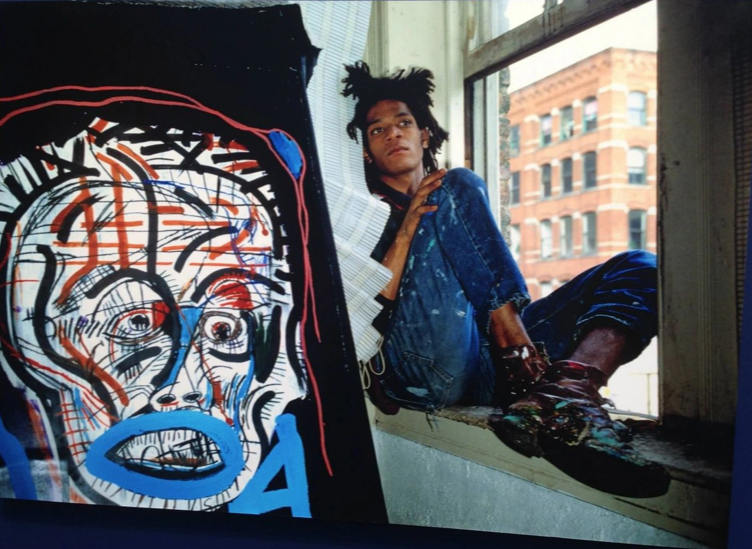

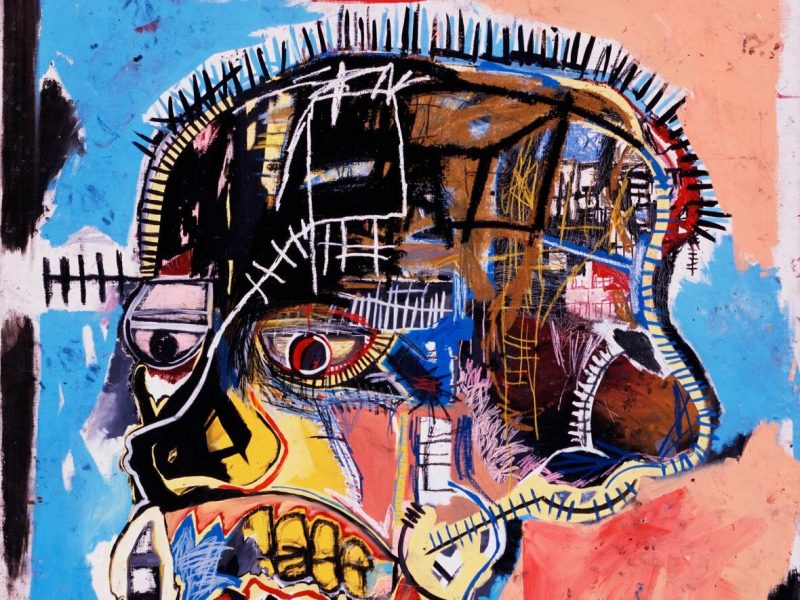

A thematic presentation of the groundbreaking and provocative art of Jean-Michel Basquiat, this volume offers a new appreciation of his tragic but highly influential career. From his early years spray painting the walls of lower Manhattan to his first solo show in 1982 and his untimely death at the age of 27 in 1988, Jean-Michel Basquiat has become a symbol of the 1980s New York art scene. Now, more than a quarter-century since his death, this book considers Basquiat’s works in light of their transformative power. Exquisitely reproduced full-page color illustrations of his paintings cover the full thematic range of Basquiat’s work. From the autobiographical elements of Untitled (1981) and the powerful critique of racial justice that is Irony of a Negro Policeman to an exploration of black heroes, Untitled (1982) and the tongue-in-cheek social commentary of A Panel of Experts, Basquiat’s limitless palette of observation, criticism, and cultural references endows his art with lasting and provocative power. Author Dieter Buchhart explores how Basquiat’s success paved the way for an entire generation of black artists and how street culture has spread into popular culture. Texts by curators, art dealers, and cultural critics discuss the significance of Basquiat’s oeuvre and show how his approach and subject matter continue to influence artists around the world

JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT: NOW’S THE TIME

EXHIBITION OVERVIEW

Jean-Michel Basquiat took the New York City art world by storm in the early 1980s and gained international recognition by creating powerful and expressive works that confronted issues of racism, identity and social tension. Although his career was cut short by his untimely death at age 27, his groundbreaking drawings and paintings continue to challenge perceptions, provoke vital dialogues and empower us to think critically about the world around us. Jean-Michel Basquiat: Now’s the Time marks the first major retrospective of the artist’s work in Canada and will feature close to 85 large-scale paintings and drawings from private collections and public museums across Europe and North America.

Guest-curated by renowned Austrian art historian, curator and critic Dieter Buchhart, the AGO’s exhibition will be the first thematic examination of the artist’s work. Inspired as much by high art — Abstract Expressionism and Conceptualism — as by jazz, sports, comics, remix culture and graffiti, Basquiat translated the world around him into a provocative visual language.

Jean Michel Basquiat

In the 1980s, as a member of the Neo-expressionist movement, American artist Jean-Michel Basquiat(December 22, 1960 – August 12, 1988) achieved success.

As a member of the graffiti duo SAMO with Al Diaz in the late 1970s, when rap, punk, and street art came together to form the early hip-hop music scene, Basquiat first rose to recognition by creating enigmatic epigrams. His works were on display in galleries and museums all over the world by the start of the 1980s. At age 21, Basquiat made history by participating in Documenta in Kassel, Germany, as the youngest artist ever. He was one of the youngest artists to display at the Whitney Biennial in New York at the age of 22. In 1992, his works were featured in a retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

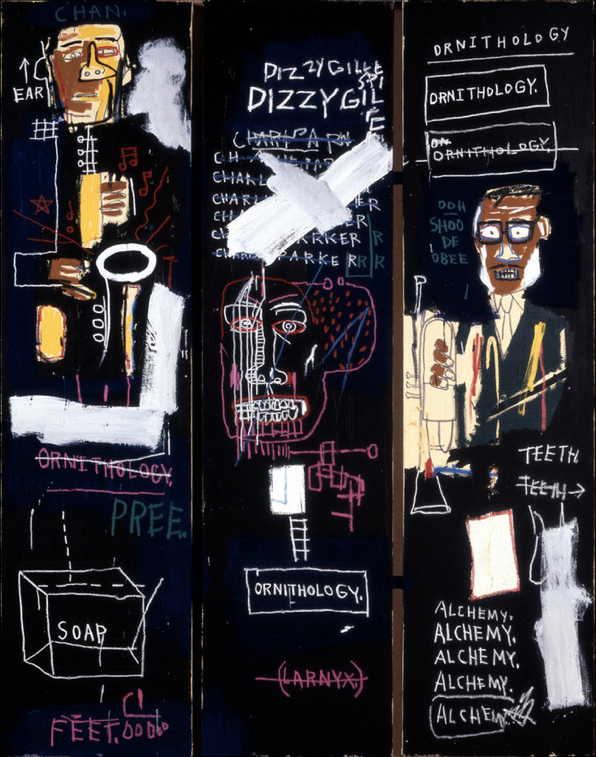

The dichotomies of wealth against poverty, integration versus segregation, and inner versus exterior experience were major themes in Basquiat’s work. He combined text and picture, abstraction and figuration, historical details and modern critique, and he appropriated poetry, drawing, and painting. In addition to criticizing racial injustice and power structures, he employed social commentary in his paintings as a means of self-examination and identification with the experiences he had growing up in the black community. His visual poetry was sharply political, blunt in its opposition to colonialism, and supportive of the working class.

When Basquiat passed away in 1988 at the age of 27, the worth of his artwork has risen steadily. One of the most expensive paintings ever acquired, Untitled, a 1982 picture of a black skull with red and yellow rivulets, sold for a record-breaking $110.5 million in 2017.

Basquiat was the second of Matilde Basquiat’s four children (née Andrades, 1934–2008) and Gérard Basquiat’s four children when he was born on December 22, 1960, in Park Slope, Brooklyn, New York City (1930–2013). He had two younger sisters, Lisane (b. 1964) and Jeanine, as well as an elder brother, Max, who passed away just before he was born (b. 1967). His mother was born in Brooklyn to Puerto Rican parents, while his father was born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. His upbringing was Catholic.

By bringing her young son to nearby museums and enrolling him as a junior member of the Brooklyn Museum of Art, Matilde nurtured a love of art in him. Basquiat was a bright youngster who could read and write by the time he was four. His mother praised his artistic ability, and he frequently tried to recreate his favorite cartoons. He began going to the elite Saint Ann’s School in 1967. There, he ran across his buddy Marc Prozzo, and the two collaborated to write and illustrate a children’s book, which was written by Basquiat when he was seven years old.

At the age of seven, Basquiat was struck by a car in 1968 as he played on the street. He had many internal injuries that necessitated a splenectomy, along with a shattered arm. His mother gave him a copy of Gray’s Anatomy to keep him entertained while he was in the hospital. Basquiat and his sisters were reared by their father when his parents divorced in that same year. When he was ten years old, his mother was admitted to a mental hospital, and she spent the rest of her life in and out of institutions. Basquiat was a voracious reader and a trilingual speaker by the time he was eleven years old.

The family of Basquiat first lived in the Boerum Hill area of Brooklyn before relocating to Miramar, Puerto Rico, in 1974. In 1976, when they moved back to Brooklyn, Basquiat enrolled at Edward R. Murrow High School. As a teenager, he struggled to cope with his mother’s instability and rebelled. When he was 15, his father saw him smoking marijuana in his room, and he fled the house. He consumed acid while dozing off on park seats in Washington Square Park. The cops were summoned to bring him home after his father eventually noticed him with a shorn head.

He enrolled at City-As-School at Manhattan’s alternative high school for kids who struggled in traditional education while they were in the tenth grade. He would skip class with his pals, but his teachers would still encourage him, and he started to write and draw for the school newspaper. In order to promote a fake religion, he created the character SAMO. As an acronym for the expression “Same old shit,” “SAMO” first emerged as a private joke between Basquiat and his classmate Al Diaz. Before and after using SAMO, they created a series of cartoons for their school newspaper.

Basquiat and Diaz started spray painting graffiti on Lower Manhattan buildings in May 1978. Operating under the alias SAMO, they penned humorous and poetic commercial slogans like “SAMO AS AN ALTERNATIVE TO GOD.” Basquiat was expelled from City-As-School in June 1978 after punching the principal. When he chose to stop attending school at age 17, his father ejected him from the house. He continued to make graffiti at night while working at the Unique Clothes Warehouse in NoHo. The Village Voice published a piece about the SAMO graffiti on December 11, 1978.

Basquiat made an appearance on Glenn O’Brien’s live public access television program TV Party in 1979. Basquiat and O’Brien became friends, and during the following few years, he frequently appeared on the program. [34] He eventually started spending time around the School of Visual Arts creating graffiti, where he became friends with classmates John Sex, Kenny Scharf, and Keith Haring.

At the Canal Zone Party in April 1979, Basquiat and Michael Holman started the noise rock group Test Pattern, subsequently became Gray. Shannon Dawson, Nick Taylor, Wayne Clifford, and Vincent Gallo were more Gray members. In nightclubs including Max’s Kansas City, CBGB, Hurrah, and the Mudd Club, they gave performances.

Basquiat and his friend Alexis Adler, a recent Barnard biology graduate, were residing in the East Village at this time. He frequently reproduced chemical compound representations from Adler’s science texts. She captured Basquiat’s artistic excursions as he turned the furniture, doors, walls, and floors into his works of art. Along with his friend Jennifer Stein, he also created postcards. Basquiat saw Andy Warhol and art critic Henry Geldzahler at W.P.A. restaurant while he was hawking postcards in SoHo. He offered Dumb Games, Poor Ideas, a postcard for sale to Warhol.

In October 1979, Basquiat displayed his SAMO montages utilizing color Xerox copies of his artwork at Arleen Schloss’s open space known as A’s.

Basquiat was able to use the location to produce his painted upcycled clothing known as “MAN MADE” thanks to Schloss. Costume designer Patricia Field carried his clothes collection in her posh East Village store on 8th Street in November 1979. In the shop window, Field also had his sculptures on display.

In 1980, after a fight with Diaz, Basquiat wrote “SAMO IS DEAD” on the walls of SoHo structures. He made his first appearance in a national magazine, High Times, in June 1980. Glenn O’Brien wrote a piece titled “Graffiti ’80: The Status of the Outlaw Art” that featured him. Later that year, he started shooting O’Brien’s independent movie Downtown 81 (2000), which was first called New York Beat and had some of Gray’s tracks on its soundtrack.

In June 1980, Collaboration Projects Incorporated (Colab) and Fashion Moda sponsored the multi-artist event The Times Square Show, in which Basquiat took part. Jeffrey Deitch, who wrote about him in an article titled “Report from Times Square” in the September 1980 issue of Art in America, was one critic and curator who took note of him. Basquiat took part in the Diego Cortez-curated New York/New Wave exhibition in February 1981 at New York’s P.S. 1. Italian dealer Emilio Mazzoli was introduced to Basquiat’s work by Italian artist Sandro Chia, who instantly purchased 10 of the artist’s works so that Basquiat could have a display at his gallery in Modena, Italy, in May 1981. The first in-depth essay about Basquiat was “The Radiant Kid,” written by art critic Rene Ricard and published in Artforum magazine in December 1981. During this time, Basquiat painted numerous works on items he discovered in the streets, such abandoned doors.

Following their collaboration on the Downtown 81 film, Debbie Harry, the lead singer of the punk rock band Blondie, purchased Cadillac Moon (1981), Basquiat’s debut painting, for $200. In the 1981 Blondie song video “Rapture,” he also played a disc jockey, a role that was initially written for Grandmaster Flash. During the time, Basquiat shared a residence with his lover Suzanne Mallouk, who worked as a waitress to support him financially.

On the advice of Sandro Chia, art dealer Annina Nosei encouraged Basquiat to join her gallery in September 1981. He took part in her group exhibition Public Speaking not long after that. She gave him supplies and a place to work in the gallery’s basement. Nosei made arrangements for him to relocate to a loft that doubled as a studio at 101 Crosby Street in SoHo in 1982. In March 1982, he held his first US solo exhibition at the Annina Nosei Gallery. At his second Italian exhibition in March 1982, he also painted in Modena. That show was canceled because he was required to produce eight paintings in a single week, and he felt abused.

During the summer of 1982, Basquiat had departed the Annina Nosei Gallery, and Bruno Bischofberger, a gallerist, had taken over as his representative internationally. At age 21, Basquiat was the youngest artist to ever participate at Documenta in Kassel, Germany, in June 1982. His works were displayed alongside those of Andy Warhol, Gerhard Richter, Cy Twombly, Joseph Beuys, and Anselm Kiefer. In September 1982, Bischofberger hosted a solo exhibition of Basquiat’s work in his Zurich gallery, and on October 4, 1982, he set up a lunch meeting between Basquiat and Warhol. According to Warhol, “I snapped a Polaroid, he went home, and within two hours a painting of him and I together was returned, still wet.” Dos Cabezas (1982), an artwork, sparked their friendship. James Van Der Zee took a photo of Basquiat for a Henry Geldzahler interview that appeared in Warhol’s Interview magazine’s January 1983 issue.

The Fun Gallery in the East Village hosted Basquiat’s solo exhibition, which debuted in November 1982. The pieces on display included Equals Pi and A Panel of Experts, both from 1982. (1982). Basquiat started working in the studio facility that art dealer Larry Gagosian had constructed beneath his Venice, California house in early December 1982. He started a series of paintings there for a March 1983 exhibition, his second at the West Hollywood Gagosian Gallery. His lover, the at-the-time unknown singer Madonna, was with him. According to Gagosian, “Everything was operating smoothly. We were having a great time while I was selling Jean-paintings Michel’s and he was creating his own. Jean-Michel eventually said, “My girlfriend is coming to reside with me,” though. So I asked, “So, how is she?” “Her name is Madonna, and she’s going to be huge,” he continued. He mentioned something that I’ll never forget.”

The artwork that Robert Rauschenberg was creating at Gemini G.E.L. in West Hollywood piqued Basquiat’s interest. He visited him frequently and took encouragement from his achievements. While living in Los Angeles, Basquiat created the painting Hollywood Africans (1983), which features him alongside the graffiti artists Rammellzee and Toxic. With pieces like Portrait of A-One A.K.A. King (1982), Toxic (1984), and ERO, he frequently created portraits of other graffiti artists, sometimes working in collaboration with them (1984). He created the hip-hop song “Beat Bop” in 1983, which featured Rammellzee and rapper K-Rob. It was only printed in a small number of copies under his Tartown Inc. imprint. The single’s cover art was designed by him, making it very popular with both record and art collectors.

At the age of 22, Basquiat was one of the youngest artists to take part in the Whitney Biennial exhibition of modern art in March 1983. In April 1983, Paige Powell, an associate publisher for Interview magazine, hosted a display of his artwork in the residence of a friend in New York. Soon after, he started dating Powell, who was important in helping him develop his bond with Warhol. At 57 Great Jones Street in NoHo, a Warhol-owned loft that also acted as a studio, Basquiat moved in in August 1983.

Basquiat invited Lee Jaffe, a former member of Bob Marley’s band, to travel with him through Asia and Europe in the summer of 1983. Michael Stewart, a budding black artist in the downtown club scene who was assassinated by transit police in September 1983, left a profound impression on him upon his return to New York. In response to the event, he created Defacement (The Death of Michael Stewart) (1983). In 1983, he additionally took part in a Christmas fundraiser for the Stewart family with a number of other New York artists.

Basquiat had his first exhibition at Mary Boone’s SoHo gallery in May 1984 after joining in 1983. Several images show Warhol and Basquiat working together in the years 1984 and 1985. When they worked together, Warhol would begin with a very precise idea or recognized image, which Basquiat would later deface in his lively manner. Olympics was their homage to the 1984 Summer Olympics (1984). Other partnerships exist, such as Taxi, 45th/Broadway (1984–85), and Zenith (1985). After their joint exhibition, Paintings, at the Tony Shafrazi Gallery was slammed by critics and Basquiat was referred to as Warhol’s mascot, their friendship soured.

Basquiat frequently painted in pricey Armani outfits and would show up in public wearing the same garments covered in paint. He frequently frequented the Area nightclub, where he occasionally performed as a DJ for amusement. Moreover, he created murals for New York City’s Palladium nightclub. In the media, his quick ascent to stardom was documented. He was featured in the article “New Art, New Money: The Marketing of an American Artist” that was on the cover of The New York Times Magazine’s issue from February 10, 1985. He was interviewed for MTV’s “Art Break” segment, and his art has been featured in GQ and Esquire. He appeared on the Comme des Garçons Spring runway in New York in 1985.

Midway through the 1980s, Basquiat was making $1.4 million a year and getting one-time payments from art dealers of $40,000. His emotional instability followed him despite his accomplishments. Basquiat’s drug use and paranoia increased as his wealth increased, according to journalist Michael Shnayerson. Because of his severe cocaine use, Basquiat ruptured his nasal septum. According to a friend, late in 1980, Basquiat admitted to using heroin. Many of his contemporaries theorized that he turned to drugs as a way to deal with the pressures of his newfound popularity, the exploitative nature of the art business, and the pressures of being a black man in a white-dominated field.

In January 1986, Basquiat traveled back to Los Angeles for his exhibition at the Gagosian Gallery, which would be his final on the West Coast.

Basquiat came to Atlanta, Georgia, in February 1986 for a drawing exhibition at the Fay Gold Gallery.

He took part in the Limelight organization’s Art Against Apartheid fundraiser that month. In the summer, he held a one-man show at Salzburg’s Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac. Moreover, he was given the opportunity to walk the runway once more for Rei Kawakubo, at the Comme des Garçons Homme Plus fashion show in Paris. Bruno Bischofberger organized a Basquiat exhibition at the French Cultural Institute in Abidjan in October 1986, so the artist took a plane there. He was joined by his girlfriend Jennifer Goode, who worked at Area nightclub, which he frequently frequented. In November 1986, when he was 25 years old, Basquiat made history by becoming the youngest artist to have a show at Hanover, Germany’s Kestner-Gesellschaft.

Since she had access to drugs during their relationship, Goode started sniffing heroin with Basquiat. She claimed, “He didn’t force it on me, but it was just there and I was so naive. She was successful in enrolling Basquiat and herself in a methadone program in Manhattan toward the end of 1986, but he left after three weeks. Goode claims that he didn’t begin injecting heroin prior to her ending their relationship. Basquiat had a bit of a reclusive personality in the last 18 months of his life. It is believed that his continuing drug usage was a coping mechanism for him following the death of his friend Andy Warhol in February 1987.

Basquiat held shows in 1987 at the Tony Shafrazi Gallery in New York, the Akira Ikeda Gallery in Tokyo, and Galerie Daniel Templon in Paris. For André Heller’s Luna Luna, a transient amusement park in Hamburg that operated from June to August 1987 and featured rides created by well-known modern artists, he created a Ferris wheel.

Basquiat made trips to Düsseldorf and Paris in January 1988 in preparation for his exhibitions at the Hans Mayer Gallery and the Yvon Lambert Gallery, respectively. He made friends with Ivorian artist Ouattara Watts while he was in Paris. They agreed to take a trip to Korhogo, where Watts was born, that summer. After having a show in April 1988 at the Vrej Baghoomian Gallery in New York, Basquiat went to Maui in June to stop using drugs. In July, after arriving back in New York, Basquiat ran into Keith Haring on Broadway. According to Haring, this was the only time they had ever spoken about Basquiat’s drug use. Glenn O’Brien said that Basquiat had contacted him and expressed how “wonderful” he was feeling.

Despite his attempts at recovery, Basquiat passed away from a heroin overdose on August 12, 1988, at the age of 27, in his Manhattan residence on Great Jones Street. His fiancée Kelle Inman had discovered him unconscious in his bedroom and brought him to Cabrini Medical Center, where he was already dead when they got there.

Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn is where Basquiat is laid to rest. On August 17, 1988, a private funeral was performed at Frank E. Campbell Funeral Home. Family members and close acquaintances, including Keith Haring, Francesco Clemente, Glenn O’Brien, and Basquiat’s ex-girlfriend Paige Powell, attended the funeral. Jeffrey Deitch, an art dealer, gave a eulogy.

On November 3, 1988, Saint Peter’s Church had a public memorial. Ingrid Sischy, the editor of Artforum, who got to know Basquiat well and commissioned several articles introducing his work to the general public, was one of the presenters. Suzanne Mallouk, Basquiat’s ex-girlfriend, delivered passages from A. R. Penck’s “Poem for Basquiat,” while Fab 5 Freddy, a friend of the artist, read a poem by Langston Hughes. Glenn O’Brien, Keith Haring, David Shapiro, Glenn O’Brien, and members of Basquiat’s old band Gray were among the 300 attendees.

Keith Haring painted A Pile of Crowns for Jean-Michel Basquiat as a tribute to the late artist. Haring said the following in the obituary he wrote for Vogue: “In just ten years, he produced a lifetime’s worth of art. Greedily, we speculate about what other works he may have produced and what masterpieces his passing has denied us access to, but the truth is that he has left behind a body of work that will continue to fascinate future generations. Just now are people starting to realize how significant his contribution was “.

Franklin Sirmans, an art critic, said that Basquiat appropriated poetry, drawing, and painting and combined text and image, abstraction, figuration, and historical data with modern criticism. His social critique was sharply political, blunt, and supportive of class struggle and colonialism. He also looked into a variety of artistic traditions, including the Classical tradition. Basquiat’s self-identification as an artist, according to art historian Fred Hoffman, may have been rooted in his “innate capacity to function as something akin to an oracle, distilling his perceptions of the outside world down to their essence and, in turn, projecting them outward through his creative act,” and his work centered on recurrent “suggestive dichotomies” like wealth versus poverty, integration versus segregation, and inner versus outer experience.

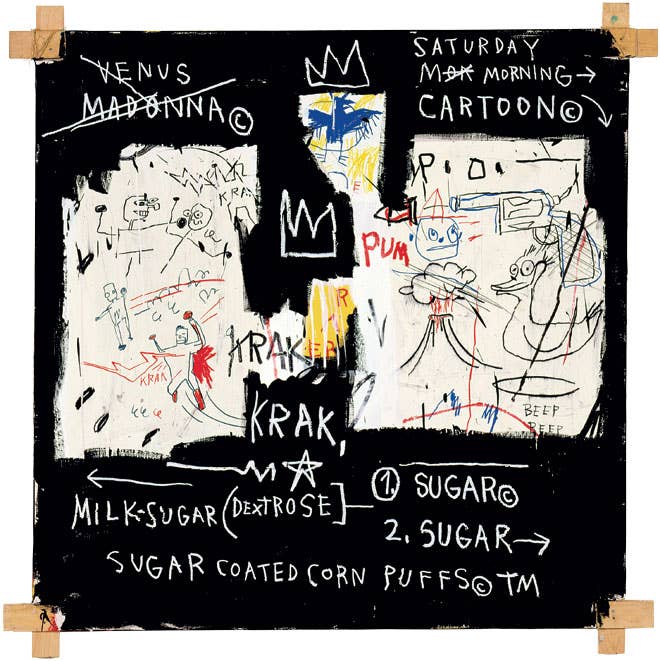

Before starting his career as a painter, Basquiat created punk-inspired postcards to sell on the street and rose to fame as SAMO for his political and poetic graffiti. He frequently drew on unexpected surfaces and items, including other people’s clothes. His art incorporates a variety of media in unique ways. His works frequently feature many sorts of codes, including words, characters, numbers, pictograms, logos, map symbols, and diagrams.

Texts were mostly used by Basquiat as reference material. Among the books he used were Burchard Brentjes’ African Rock Art, Flash of the Spirit by Robert Farris Thompson, Leonardo da Vinci published by Reynal & Company, Henry Dreyfuss’ Symbol Sourcebook, Gray’s Anatomy, and Henry Dreyfuss’ Symbol Sourcebook.

Between late 1982 and early 1985, multi-panel paintings and single canvases with exposed stretcher bars were popular. The surfaces of these works were heavily embellished with writing, collage, and images. The Basquiat and Warhol collaborations took place from 1984 to 1985.

During the course of his brief but productive career, Basquiat created roughly 1,500 drawings, 600 paintings, several sculptures, and mixed-media pieces. He regularly drew and frequently used nearby objects as surfaces when paper wasn’t readily available. Drawing became a component of his artistic expression as a child when his mother’s love in art led him to create cartoon-inspired drawings. He used a variety of drawing tools, but his preferred ones were ink, pencil, felt-tip or marker, and oil-stick. He occasionally pasted bits of his drawings that were Xerox copies onto the canvases of larger works.

At the MoMA PS1 New York/New Wave exhibition in 1981, Basquiat’s paintings and sketches were first displayed in front of the general public. The art world first became aware of Basquiat through Rene Ricard’s article “Radiant Child” in the magazine Artforum. With two drawings, Untitled (Axe/Rene) (1984) and René Ricard, Basquiat rendered Ricard immortal (1984).

His notebooks and other significant drawings show that he was both a poet and an artist. Words were prominent in his drawings and paintings, with explicit references to racism, enslavement, the people and street scene of 1980s New York, black historical figures, famous musicians, and athletes. Since Basquiat’s artworks were frequently left nameless, a word that was included in the picture is frequently included in parentheses after Untitled to distinguish pieces. Gérard Basquiat, who managed the committee that certified artworks and met from 1994 until 2012 to examine more than 2000 pieces, the most of which were drawings, was in charge of Basquiat’s estate after he passed away.