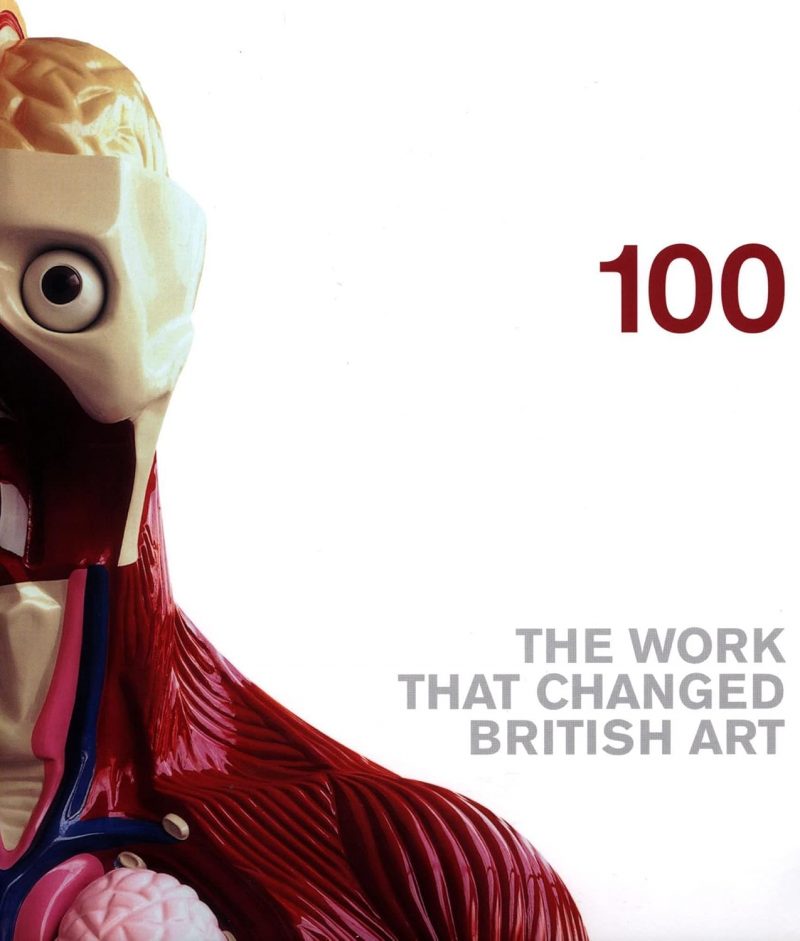

‘100: The Work that Changed British Art’ Hardcover, 2003

100 – The Work That Changed the Art World, Saatchi Gallery, 2003

100 is the book that will mark the occasion with one hundred works that Saatchi believes made a difference to the perception of British art.

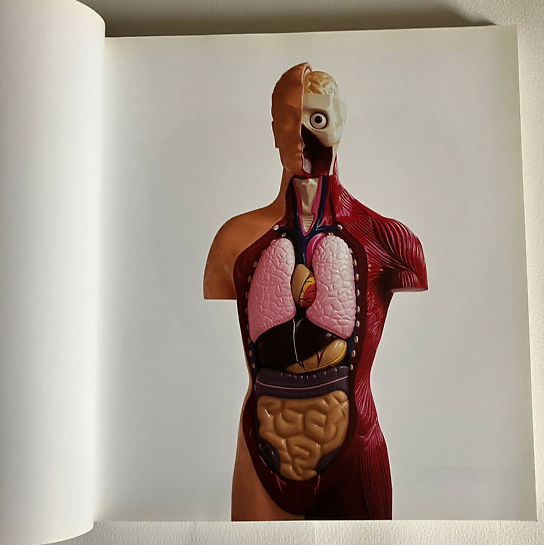

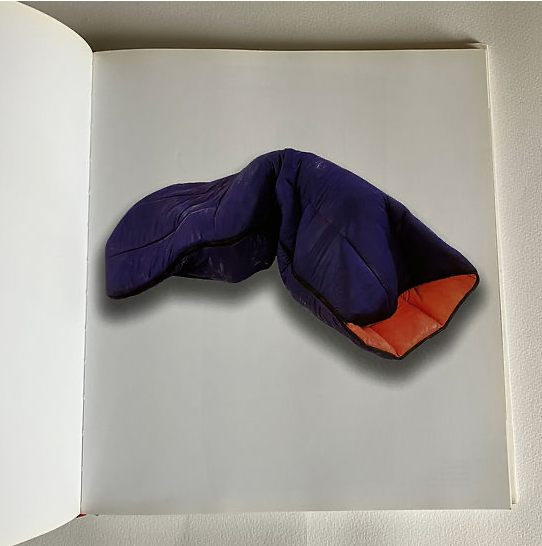

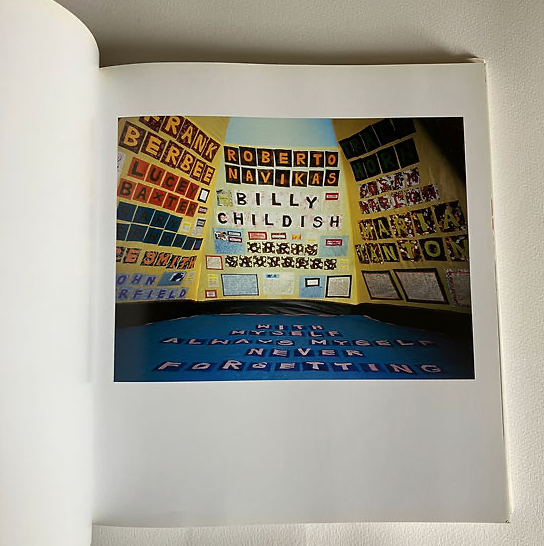

The work of twenty-seven artists have been chosen from Saatchi’s collection and of course the selection includes the shark and the sheep in formaldehyde, the head made of blood and Tracey’s bed.

It is a landmark publication for a landmark occasion.

After the provocation of the famous Sensation show at the Royal Academy in 1997, a generation of young artists have become household names. What was once so provocative has now entered the visual vocabulary of a wider public. What was once so daring is now demonstrated to be more than ephemeral. Saatchi’s vision is defined in 100.

Published by Jonathan Cape in association with The Saatchi Gallery in 2003.

Hardcover, first edtion, 224 pages in good condition.

Product Details:

- Publisher : Random House UK; Illustrated edition (April 1, 2006)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 240 pages

- Item Weight : 2.9 pounds

- Dimensions : 9.3 x 0.96 x 10.4 inches

PRESS:

The Trophy Room

The Mini decorated with Damien Hirst dots is parked halfway down the grand staircase at London’s County Hall, like a leftover prop from a Bond movie, or a stalled gag from one of those spoof, Brit-spook movies that keep doing the rounds. At the bottom of the stairs is a nasty sculpture made of dead rats with thrashing pink tails, and a couple of lifelike, life-sized figures by US super-realist sculptor Duane Hanson. Just as the imaginary movie starts running in my head – Charles Saatchi, evil mastermind, kidnaps Horace Cutler, bow-tied leader of the London County Council, threatening to have him sliced, diced and thrown to the flies in a macabre vitrine up on the first floor – a smiling PR trips lightly down the stairs, breaking the spell.

It won’t do. I can’t make light of the Saatchi Gallery at County Hall. I wanted to visit the place with something like an open mind, but it is impossible. Most of the work here, recent though it is, has too much history to be seen afresh, and the publicity, gossip and regurgitated profiles of the collector keep getting in the way. So does County Hall itself, once home of the LCC and the GLC. Now the Saatchi Gallery joins the ludicrous Salvador Dali Universe, an aquarium, a temporary exhibition dedicated to Madonna and a US chain hotel in the former seat of London’s local government.

The little map on the hand-out makes the gallery look as if it occupies the entirety of County Hall, and is so out of scale it appears bigger than the Houses of Parliament across the Thames, from where one can read the gallery signage over the central, riverside portico. Once, Ken Livingstone’s daily count of London’s unemployed was writ large on County Hall’s walls, a rebuke to the Thatcherite government and their enfeebled Labour opposition on the north bank. It was Saatchi & Saatchi ad campaigns that told us Labour wasn’t working, and there is still something disturbing about the Saatchi Gallery’s presence here. We haven’t even reached the art yet.

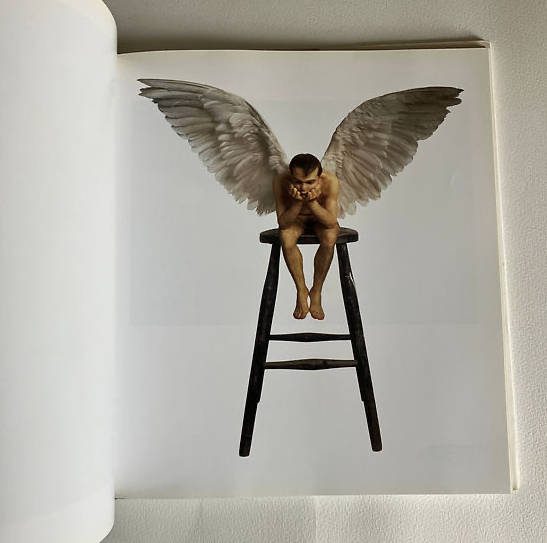

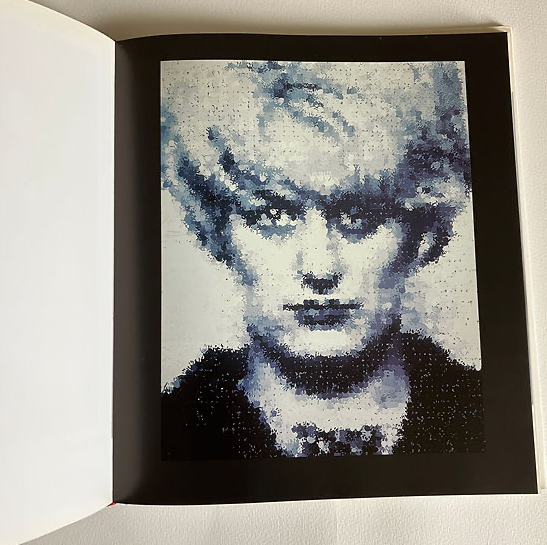

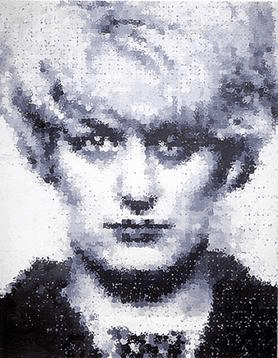

Here are the flies, buzzing around the cow’s head and being zapped, in Hirst’s great 1990 work A Thousand Years. Here is the shark, and Tracey Emin’s Bed, Chris Ofili’s Holy Virgin Mary and Marc Quinn’s head, cast in his own frozen blood. Here is Ron Mueck’s Dead Dad and Marcus Harvey’s Myra Hindley. The lamb in the tank is somewhere hereabouts, and lots more Hirst, in what amounts to a fudged mini-retrospective, without a proper catalogue or overview, for which the artist should be less than grateful. Having Mueck’s little angel look down from a cornice on Hirst’s art is a crass curatorial conceit.

This is no longer the way – if ever it was – to display or contextualise either the art in Saatchi’s collection or the artists whom his collection represents. Many of the best-known works here are thrown together in the municipal splendour of what was once the debating chamber. The works in this grand, pillared space die under the architecture and in each other’s company; they are shrunken somehow, cowed by the building and the collector’s dead hand. It has become a hall of the living dead. It is not a gallery, but a trophy room.

Many of the earlier works here were first seen in empty warehouses and offices whose walls had been torn down. There, and in the white-walled paint factory that Saatchi converted into his first gallery 18 years ago, they stood alone, with a certain dignity, implacable and austere. Here, they are so much stuff.

The works displayed alone in the empty offices that line the endless corridors fare better, but there is a sense that they too have been left to sequester and die, like ageing civil servants waiting for retirement day. Even here, the rooms – with their ornate fireplaces and stopped clocks – take over. The memory of desks with Bakelite telephones, piled with foolscap, and meetings among men who had been in the wars, remains. The woodwork is steeped in a sadness and a sense of futile industry and propriety that won’t go away. Sticking early Peter Doig and Jenny Saville paintings in ornate, old-masterish frames doesn’t deal with the inappropriateness of their setting either. It makes them even more trapped.

The only astonishing moment is when one enters Richard Wilson’s relocated 20:50, his oil room, where one walks out on a pier in a space half-drowned in pure reflection, the oil flipping the full-length windows and 1920s architectural detailing in its pure black glare. For theatrical effect, a door has been left half-open across the oily pond, the reflections continuing on, out of sight. This is a disturbing, Magrittean moment – a work that feeds on the complicated space that contains it.

The rest of the collection feels diminished, by the building, by the little information panels, and the book from which they come. For Patricia Ellis, who wrote this stuff, the art in the Saatchi Gallery is “a New Age gospel based on age-old art tradition”. Ugh. Hirst, she says, is “the alpha-male of contemporary British art” and his motorised pig sliced down the middle “is a parody of the futile rat race of life”. Rats? Pigs? One species at a time, please. Ellis has Jenny Saville as “a Francis Bacon or Lucian Freud for a new generation”, while Sarah Lucas “constructs a downtrodden feminism, based on a working class salt-of-the-earthiness”. As for Tracey Emin, Ellis’s in-depth commentary says that “every time she appears in newspapers and on the telly, she is essentially making the ‘non-art’ world compliant participators in her practice”.

This misinformative nonsense is matched by Saatchi’s own skewed version of the world. The British artists who emerged in the 1990s, he says, “are now galvanising students in Britain’s art colleges where they have many admirers and ‘schools of'”. Yet Saatchi concludes: “There’s no neat link … no school, just a very direct, almost infantile energy that gives the work here its full-on, check-this-out force.” This is worse than patronising. It is embarrassing.

It gets worse. The gallery website says: “British art is the most exciting in the world and needs a dedicated showcase.” No it doesn’t. It needs to breathe, it needs to get out more and be allowed to grow up. The last thing the British artists who became famous in the 1990s need is to be forever identified with their moments of early success and their association with Charles Saatchi. These works should be put aside for a while, not least so that the artists themselves can escape the arrested moments of their early development.

Artists, if they are any good, move on and deepen their game, or change the game altogether. The parochial, defensive, passé talk about British art here won’t let them. Nor will the new Saatchi Gallery. It looks like a provincial gulag, never mind the inclusion of Duane Hanson, or Japanese photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto, or three turgid 1958 works by Kitchen Sink painter John Bratby, or the room of works by Patrick Caulfield. All this does nothing to broaden the turf, or engage us in a more informed dialogue. The master criminal has struck again, buying the works, flogging the art down the river.

· The Saatchi Gallery, London SE1, opens on Thursday. Details: 020-7823 2363. 100: The Work That Changed British Art is published by Jonathan Cape in association with the Saatchi Gallery

BOOK selling here for $200:

https://www.zimmerstewart.co.uk/product-page/100-the-work-that-changed-the-art-world-saatchi-gallery

VIEW BOOK HERE:

https://archive.org/details/100workthatchang0000unse/page/n1/mode/2up