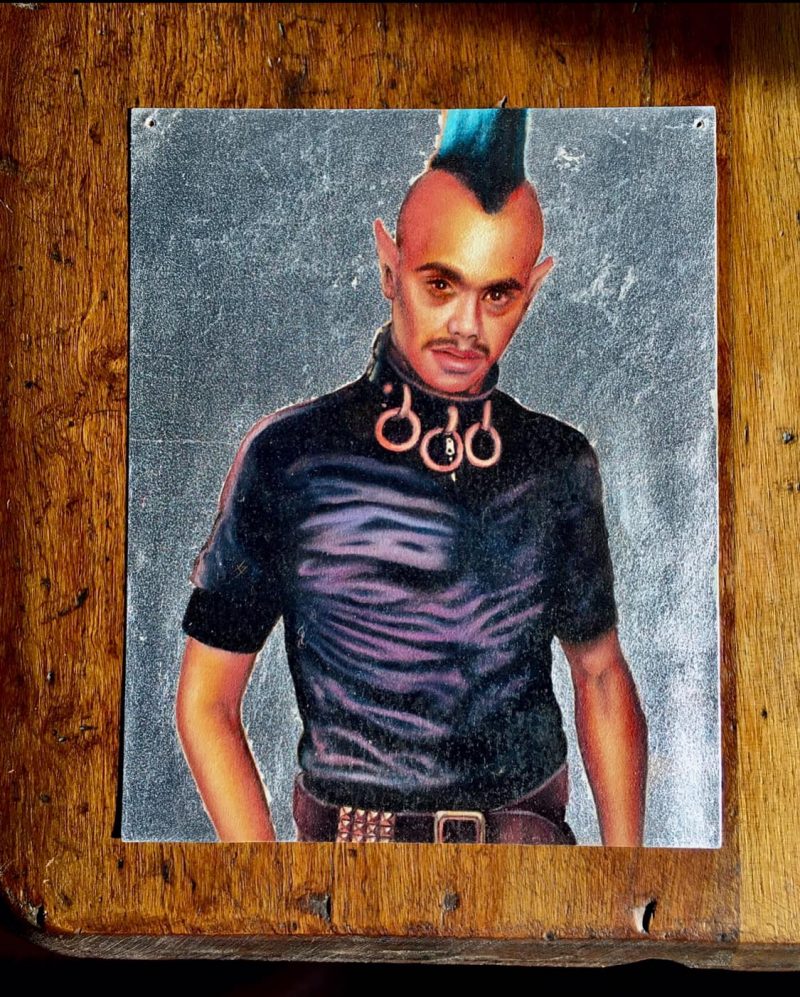

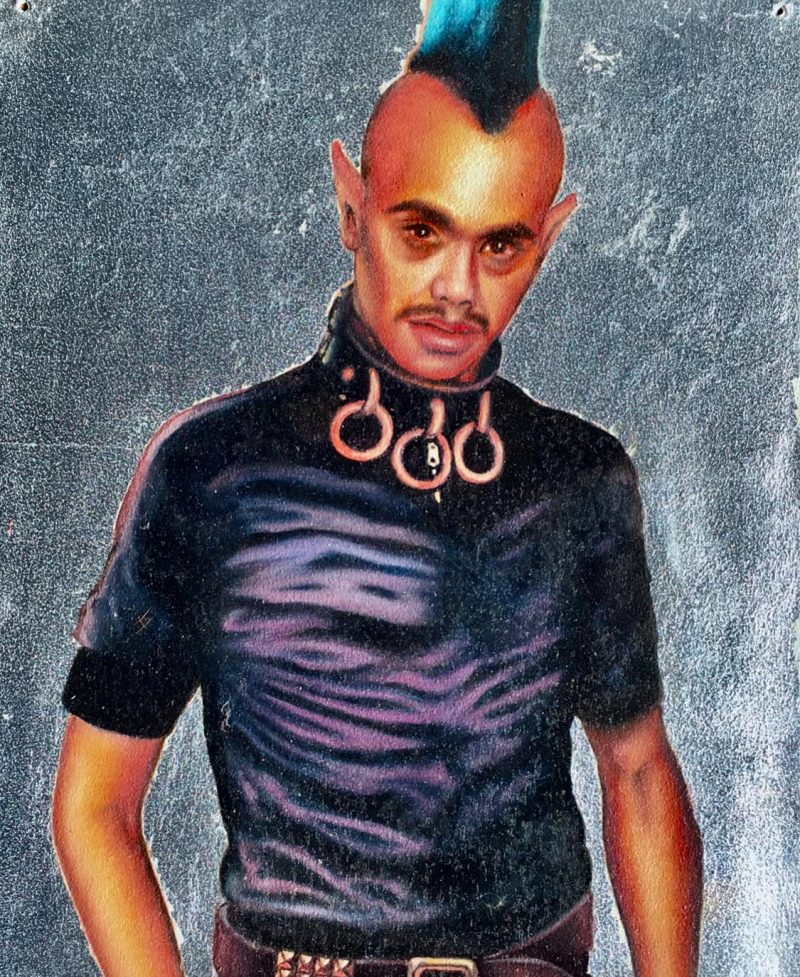

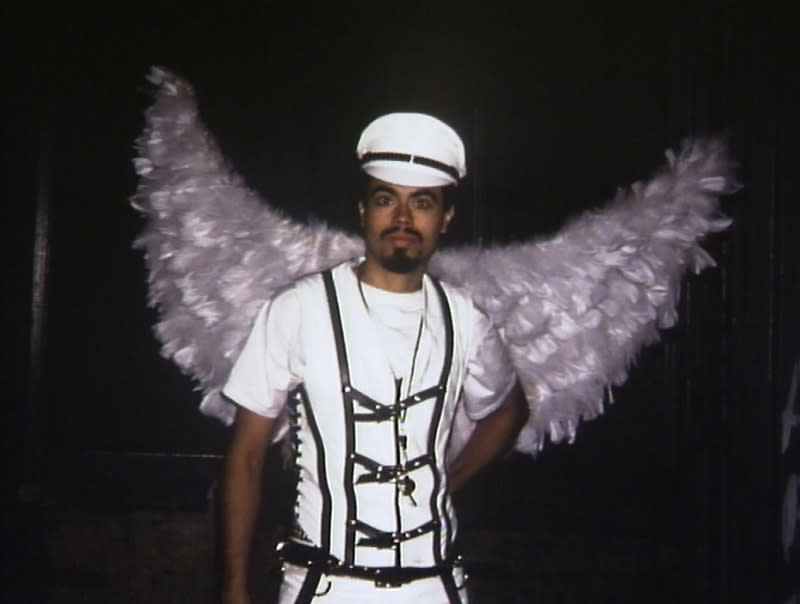

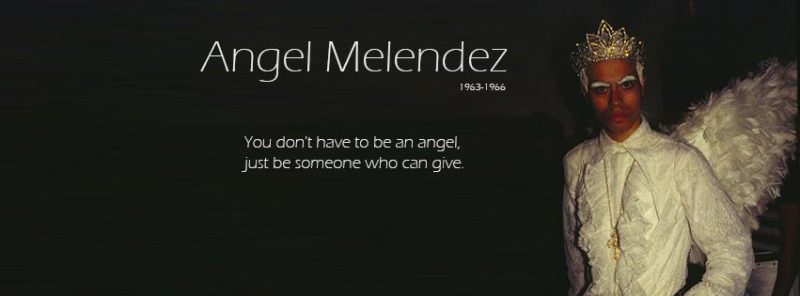

Memorial Portrait Painting, Andre ‘Angel’ Melendez, Club Kid & Infamous Drug Dealer, 2016

Memorial Portrait Painting, Andre ‘Angel’ Melendez, Club Kid & Infamous Dealer of Party Favors, murdered by Michael Alig in the nineties (New York, USA).

Oil, glitter & gold leaf on primed metal. 8×10 inches. Painting commissioned for LPM Projects & created by long time collaborator & painter Peter Shmelzer (Ottawa, Canada).

See exhibition & Day of The Dead memorial installation statement below.

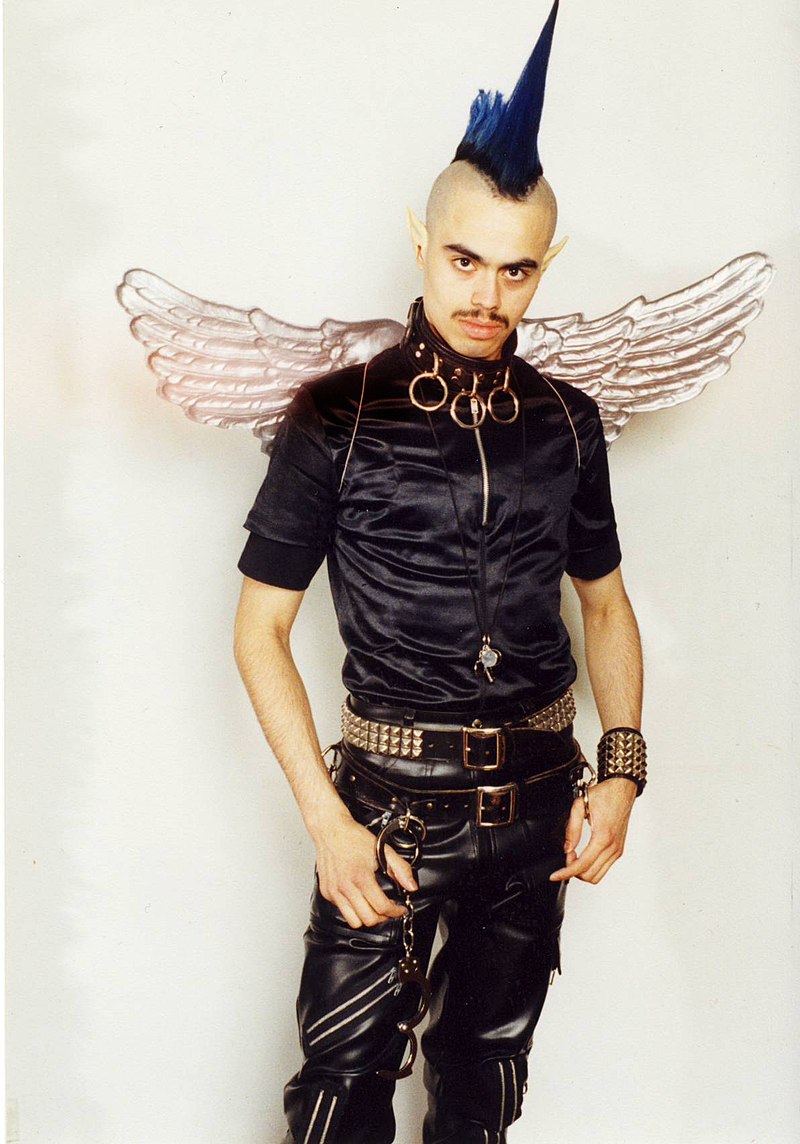

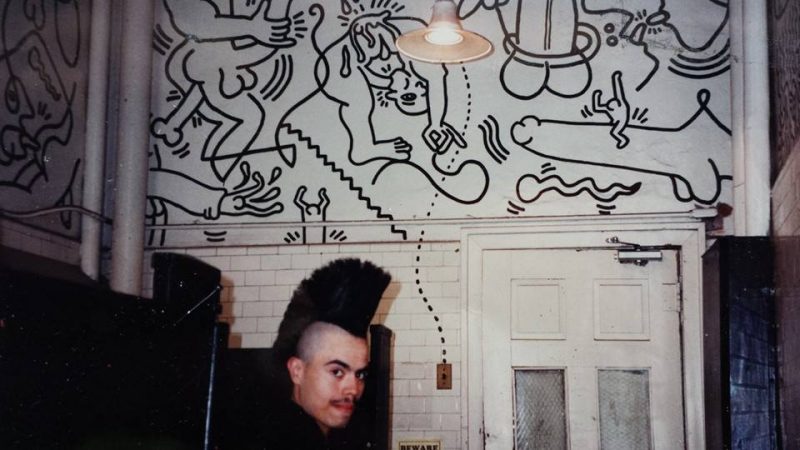

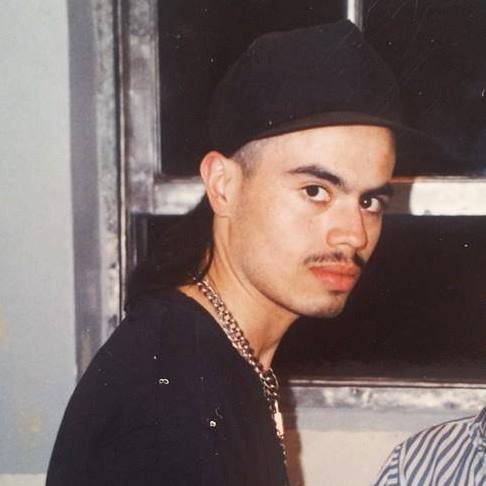

I met Angel several times in New York in the early nineties, mainly at the infamous Limelight Nightclub, and I still have his ‘dealer’ business card he gave me… for business !! He was a very sweet kid, so this portait was done out of respect.

Now availalbe for sale; Asking USD$350

Andre Melendez (May 1, 1971 – March 17, 1996) was a member of the Club Kids who lived and worked in New York City. He was killed by Michael Alig and Robert “Freeze” Riggs on March 17, 1996. His life and death have inspired several pieces of media, including books, films, music, and television.

|

Andre Melendez

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Andre Melendez

May 1, 1971 |

| Died | March 17, 1996 (aged 24) |

| Occupation | Club Kid |

| Known for |

New York City nightlife scene; his gruesome murder

|

Life

Melendez and his family arrived in New York from Colombia when Melendez was eight years old. Melendez purportedly became a drug dealer during the early 1990s after he met Peter Gatien, owner of The Limelight and several other nightclubs in New York City, and became a regular dealer in Gatien’s clubs. He was frequently seen at Manhattan clubs wearing his signature feathered wings.

Death

On Sunday, March 17, 1996, Melendez approached Michael Alig and Robert D. “Freeze” Riggs for money Melendez was purportedly owed. According to various statements, the confrontation became violent and Melendez got the better of Alig, who cried out for help. Riggs then hit Melendez on the head with a hammer, three times (until Melendez “went down”), after which Alig smothered him (either with a pillow or sweatshirt, depending upon the source), poured a “cleaner or chemical” into his mouth, then covered Melendez’s mouth with duct tape.

Alig and Riggs stripped Melendez’s body and placed it in the bathtub, where it remained for 5–7 days. According to Riggs, he then purchased “two chef knives and one cleaver” at Macy’s, with which he said Alig dismembered Melendez’s legs. The two then wrapped the legs in garbage bags, placed them into individual duffle bags and dumped in the Hudson River.

The following day, Alig and Riggs wrapped the upper body in a sheet and plastic garbage bag, placed it in a cardboard box from which Riggs had removed the UPC code, and together took the heavy box down in the elevator and through the main lobby. They then placed it in the trunk of a Yellow Cab “that happened to be right outside the door.” Riggs confessed “We took the body to the Westside Highway around 25th Street. The taxi drove off, and we threw the box into the river.”[1]

However, Alig gave some conflicting details. For example, he stated he used liquid Drano (and baking soda) to combat the smell of the malodorous decomposition after the body had been in the bathtub for several days. At first, Alig claimed the killing was in self-defense, but he later admitted to having committed manslaughter.

In the documentary film Glory Daze (2015), the police recount the discovery by a group of children at the beach at Miller Field, Staten Island, of a box containing the remains of Melendez, in March 1996. (American Justice reports the box was found in April 1996.) A tropical storm had helped propel the floating, cork-lined box to Staten Island.

Mainstream media began covering Melendez’s disappearance when the victim’s brother and father turned to the press for help and interest grew in rumors – perpetuated by Alig himself and first publicized to outsiders by Michael Musto as a blind item in his Village Voice column – that Alig and Riggs had murdered Melendez. The coincidental discovery, on Friday, September 8, 1996, of another dismembered body, fished out of the Harlem River at a pier near 134th Street by a homeless woman, sparked police to begin investigating the case in earnest. A police officer in Staten Island, who caught the Melendez media coverage, initiated an investigation of the John Doe found at Miller Field. The Staten Island Police Department used dental records to identify Melendez (whose body the coroner had mis-identified as that of an Asian male); on November 2, 1996, the mutilated corpse was positively identified as Melendez, and details of the rumors about how Melendez was killed were confirmed.

In the face of increasing police scrutiny, Alig fled to Toms River, New Jersey, where he moved into a motel room with his boyfriend, a drug dealer named Brian. On December 5, 1996, the police arrested Alig at the motel and hours later, Riggs in Manhattan. Alig insisted to the police he and Riggs had killed Melendez in self-defense, and disposed of the body in a panic. (This story contrasts sharply with the account Alig had given the victim’s brother, John (“Johnny”) Melendez, in an August 1996 conversation secretly taped by the District Attorney’s office, implicating “Melendez and club czar Gatien in a drug-dealing venture at Gatien’s nightspots,” and charging “that Riggs killed Melendez for Gatien because ‘Peter is in trouble right now for drugs’ and ‘Angel knew everything and he was threatening to go to…his friend at the Village Voice and tell him all this stuff.”) Prosecutors were hesitant to charge Alig with first-degree murder, as they still hoped he would testify against his former boss, Gatien, who had been arrested for allowing drugs to be sold in his nightclubs. They eventually offered both Alig and Riggs a plea deal: a sentence of 10 to 20 years if they accepted the lesser charge of manslaughter. On October 1, 1997, both pleaded guilty and were sentenced to 10 to 20 years. (American Justice reports they pleaded guilty and were sentenced on September 10, 1997.) Because of their convictions, Alig and Riggs were not used as prosecution witnesses in Gatien’s trial.

Convictions, Prison, and Aftermath

On October 1, 1997, Alig and Riggs were sentenced to 10 to 20 years in prison for Melendez’s killing, after each pleaded guilty to one count of manslaughter. Riggs was released on parole in 2010, Alig on May 5, 2014.

On December 24, 2020, Alig died of a drug overdose at the age of 54.

In popular culture

- Book

- James St. James‘s book, Disco Bloodbath: A Fabulous but True Tale of Murder in Clubland (1999), is about Melendez’s murder. It was reprinted with the title Party Monster after the release of the eponymous 2003 film.

- Films

- There are two films based on Melendez’s murder and the events which followed:

- The documentary film Party Monster: The Shockumentary (1998), based on the events leading up to and surrounding the Melendez’s murder.[5]

- The subsequent feature film Party Monster (2003), which stars Wilson Cruz as Melendez

- The documentary film Glory Daze (2015) reviews the creation, rise, and dispersion of the Club Kids phenomenon after Melendez’s murder.

- Music

- Melendez’s friend Screamin’ Rachael wrote the song “Give Me My Freedom/Murder in Clubland.” The lyrics to a backward loop in the song include such lines as “Michael, where’s Angel?”, and “Did someone just cry wolf, or is he dead?”[6][21]

- A 12 track concept album “a terrible beauty featuring Michael Alig” – www.satorigroup.uk – was produced in 2000 by UK-based the satori group. Track five is titled “BROTHER.” The track features, set to music, audio from the documentary “Party Monster,” with Johnny, Andre’s brother, and his fruitless search, making flyers, and talking to the police, as well as Michael Alig.

- Television

Melendez’s murder case has also been featured in multiple TV series, including:

- American Justice: “Dancing, Drugs, and Murder” (2000) on A&E[9]

- Deadly Devotion: “Becoming Angel” (July 16, 2013) on Investigation Discovery[22]

- Notorious[citation needed]

- The 1990s: The Deadliest Decade: “Death of an Angel” (Season 1, Episode 3) (Aired: November 19, 2018) on Investigation Discovery[23]

- Theatre

Clubland: The Monster Pop Party (2013), a musical adaptation of St. James’ book Party Monster and its 2003 eponymous film adaptation, debuted April 11, 2013, at the American Repertory Theater’s Club Oberon, with book, music, and lyrics by Andrew Barret Cox [24]

References

- Riggs, Robert D. (December 1996). “Club Kids Kill An Angel written confession”. The Smoking Gun. Retrieved May 10, 2014. Riggs’ written confession to the NYPD.

- Sullivan, John (September 11, 1997). “2 Men Plead Guilty in Killing of Club Denizen”. The New York Times. Retrieved March 23, 2008.

Mr. Alig, who pleaded guilty in State Supreme Court in Manhattan to one count of first degree manslaughter, admitted that he and a friend smothered Andre Melendez, known as Angel, chopped up his body and threw it into the Hudson River.

- St. James, James (1999). Disco Bloodbath: A Fabulous But True Tale of Murder in Clubland (August 11, 1999 ed.). Simon & Schuster. p. 2222. ISBN 0-684-85764-2.

- Romano, Tricia (May 9, 2014). “Michael Alig’s Next Move? ‘Club Kid Killer’ Seeks Post-Prison Job”. Billboard. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

- Bailey, Fenton (October 28, 2014). “The History of Party Monster“. WorldofWonder.net.

- Haden-Guest, Anthony (2015). The Last Party: Studio 54, Disco, and the Culture of the Night. ISBN 9781497695559.

- Fernández, Ramón (Writer and Director). Glory Daze: The Life and Times of Michael Alig (Crime documentary). Electric Theater Pictures.

- Party Monster: The Shockumentary (1998)

- Kurtis, Bill (Host) (2000). “Dancing, Drugs, and Murder”. American Justice. Episode 126. New York: A&E.

- Doonan, Simon (August 9, 1999). “Club Kids on the Skids: The Horrid, Lovely Alig Epic”. The Observer.

- Murthi, Vikram (July 26, 2018). “‘Glory Daze’ Exclusive Trailer & Poster: Explore the Rise and Fall of Michael Alig, One of NYC’s ‘Club Kids’, The film will be released on VOD on August 16”. IndieWire.

- Bar, Daryl (23 August 2016). “Review – Glory Daze: The Life And Times Of Michael Alig”. Battle Royale With Cheese.

- “REVIEW: Glory Daze – The Life and Times of Michael Alig (2015)”. World of Film Geek. December 8, 2016.

- SharKey, Alix (April 19, 1997). “Death by Decadence”. The Weekend Guardian.

- SharKey, Alix (April 19, 1997). “Death by Decadence”. The Weekend Guardian.

- Romano, Tricia. “Michael Alig: The Life and Death of the Party: Confessions of a Body Hacker”. crimelibrary.com. Archived from the original on December 21, 2014. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

- Ross, Barbara; McFarland, Stephen (January 23, 1997). “Grisly Disco-Drug Slay Tale Papers: Body Kept in Tub, Cut Up”. New York Daily News.

- Romano, Tricia. “Michael Alig: The Life and Death of the Party: Sentencing”. crimelibrary.com. Archived from the original on December 21, 2014. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

- Infamous ‘Club Kid Killer,’ Dead at 54. Yahoo News, December 26, 2020. Retrieved 2020-12-26.“Michael Alig, Infamous ‘Club Kid Killer,’ Dead at 54”.

- Goldberg, Michelle (August 16, 1999). “Clubland Horrorcoaster”. metroactive.com.

- Alig and Rachael discuss the song and its inspiration in Party Monster: The Shockumentary, starting at 41:40

- “Becoming Angel”. Investigation Discovery.

- “Death of an Angel”. Investigation Discovery.

- Blank, Matthew (April 10, 2013). “PHOTO CALL: Meet the Club Kids of the New Immersive Musical Adaptation of “Party Monster” at A.R.T.” Playbill.

The Resurrected / International Project 2016

“Raw experience tells us that there is no single, proper way to remember those that we have lost. In each instance of loss our challenge is to resist the desire to defy history, recreate the past, and bring them back. Instead, despite the rushed pace of day-to-day life, our task is to continually revive, recast, and honour our memories of them. Our task is to resurrect these memories, either in private or public, through their image, their words, and their beliefs. Born out of this commitment, Resurrected works against the grain of the traditional contemporary art formula whereby curators are expected to maintain a sense of cool academic distance to their subject matter. In stark contrast, this project is a purely instinctual curatorial gesture that bridges the gap between the personal and the public, art and life, artefact and memory.

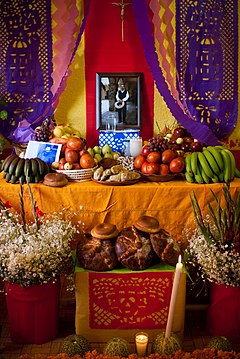

With Resurrected, curator Guy Berube reflects back 35 years to exalt the memory of individuals that have shaped his life. The project will consist of an archive of portraits held within an impermanent, hand-constructed, and site-specific altar shrine – a sort of a soft monument for the spirit of the dead, constructed in the name of life. The portraits have been produced by Ottawa-based hyperrealist painter Peter Shmelzer, a close friend and long-time collaborator. Each is constructed as a traditional prayer plate, with the clear, striking image of the individual presented in front of a modest background that is tied together with a reserved, muted pallet. Taking on a vanitas sculptural quality, the altar shrine will be furnished with fruits and vegetables, flowers, candles, and a collection of personal ephemera. Visitors are also encouraged to bring their own offerings, so that on this very rare occasion perfect strangers, both living and dead, might have the chance meet.

The portraits are modest, honest images that contain symbolism based on each individual & their circumstances. Resurrected does not imagine these individuals as deities or ghosts: Neither the individual paintings nor the complete altar shrine should be misunderstood as attempts to immortalize them. Instead, the project demonstrates that these individuals are still apart of the world, existing in and through the memories of those who carry them. It can be said, then, that the subjects of the exhibition are simply being taken on a journey. Together, they will travel to Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, a region and a site they had never visited in the material world, where the construction and maintenance of the altar shrine is set to coincide with the national Day of the Dead holiday. Resurrected takes on the spirit of the festival by occupying that difficult, yet perfectly human grey territory between mourning and ceremony, between melancholia and gratitude”.

- Written by Adam Barbu, 2016

| Day of the Dead | |

|---|---|

Día de Muertos altar commemorating a deceased man in Milpa Alta, México DF.

|

|

| Observed by | Mexico, and regions with large Hispanic populations |

| Type | Cultural Syncretic Christian |

| Significance | Prayer and remembrance of friends and family members who have died |

| Celebrations | Creation of altars to remember the dead, traditional day of the dead’s food |

| Begins | October 31 |

| Ends | November 2 |

| Date | October 31 |

| Next time | 31 October 2016 (2016-10-31) |

| Frequency | Annual |

| Related to | All Saint’s Day |

Day of the Dead (Spanish: Día de Muertos) is a Mexican holiday celebrated throughout Mexico, in particular the Central and South regions, and by people of Mexican ancestry living in other places, especially the United States. It is acknowledged internationally in many other cultures. The multi-day holiday focuses on gatherings of family and friends to pray for and remember friends and family members who have died, and help support their spiritual journey. In 2008 the tradition was inscribed in the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO.

The holiday is sometimes called Día de los Muertos in Anglophone countries, a back-translation of its original name, Día de Muertos. It is particularly celebrated in Mexico where the day is a public holiday. Prior to Spanish colonization in the 16th century, the celebration took place at the beginning of summer. Gradually it was associated with October 31, November 1 and November 2 to coincide with the Western Christian triduum of Allhallowtide: All Saints’ Eve, All Saints’ Day, and All Souls’ Day. Traditions connected with the holiday include building private altars called ofrendas, honoring the deceased using sugar skulls, marigolds, and the favorite foods and beverages of the departed, and visiting graves with these as gifts. Visitors also leave possessions of the deceased at the graves.

Scholars trace the origins of the modern Mexican holiday to indigenous observances dating back hundreds of years and to an Aztecfestival dedicated to the goddess Mictecacihuatl. The holiday has spread throughout the world, being absorbed within other deep traditions for honoring the dead. It has become a national symbol and as such is taught (for educational purposes) in the nation’s schools. Many families celebrate a traditional “All Saints’ Day” associated with the Catholic Church.

Originally, the Day of the Dead as such was not celebrated in northern Mexico, where it was unknown until the 20th century because its indigenous people had different traditions. The people and the church rejected it as a day related to syncretizing pagan elements with Catholic Christianity. They held the traditional ‘All Saints’ Day‘ in the same way as other Christians in the world. There was limited Mesoamerican influence in this region, and relatively few indigenous inhabitants from the regions of Southern Mexico, where the holiday was celebrated. In the early 21st century in northern Mexico, Día de Muertos is observed because the Mexican government made it a national holiday based on educational policies from the 1960s; it has introduced this holiday as a unifying national tradition based on indigenous traditions.

The Mexican Day of the Dead celebration is similar to other culture’s observances of a time to honor the dead. The Spanish tradition included festivals and parades, as well as gatherings of families at cemeteries to pray for their deceased loved ones at the end of the day.

Observance in Mexico

Origins

Woman lighting copal incense at the cemetery during the “Alumbrada” vigil in San Andrés Mixquic

The Day of the Dead celebrations in Mexico developed from ancient traditions among its pre-Columbian cultures. Rituals celebrating the deaths of ancestors had been observed by these civilizations perhaps for as long as 2,500–3,000 years. The festival that developed into the modern Day of the Dead fell in the ninth month of the Aztec calendar, about the beginning of August, and was celebrated for an entire month. The festivities were dedicated to the goddess known as the “Lady of the Dead”, corresponding to the modern La Calavera Catrina.

By the late 20th century in most regions of Mexico, practices had developed to honor dead children and infants on November 1, and to honor deceased adults on November 2. November 1 is generally referred to as Día de los Inocentes (“Day of the Innocents”) but also as Día de los Angelitos (“Day of the Little Angels”); November 2 is referred to as Día de los Muertos or Día de los Difuntos (“Day of the Dead”).

Beliefs

Frances Ann Day summarizes the three-day celebration, the Day of the Dead:

| “ | On October 31, All Hallows Eve, the children make a children’s altar to invite the angelitos (spirits of dead children) to come back for a visit. November 1 is All Saints Day, and the adult spirits will come to visit. November 2 is All Souls Day, when families go to the cemetery to decorate the graves and tombs of their relatives. The three-day fiesta is filled with marigolds, the flowers of the dead; muertos (the bread of the dead); sugar skulls; cardboard skeletons; tissue paper decorations; fruit and nuts; incense, and other traditional foods and decorations. | ” |

| — Frances Ann Day, Latina and Latino Voices in Literature | ||

People go to cemeteries to be with the souls of the departed and build private altars containing the favorite foods and beverages, as well as photos and memorabilia, of the departed. The intent is to encourage visits by the souls, so the souls will hear the prayers and the comments of the living directed to them. Celebrations can take a humorous tone, as celebrants remember funny events and anecdotes about the departed.

Plans for the day are made throughout the year, including gathering the goods to be offered to the dead. During the three-day period families usually clean and decorate graves; most visit the cemeteries where their loved ones are buried and decorate their graves with ofrendas (altars), which often include orange Mexican marigolds (Tagetes erecta) called cempasúchil (originally named cempoaxochitl, Nāhuatl for “twenty flowers”). In modern Mexico the marigold is sometimes called Flor de Muerto (Flower of Dead). These flowers are thought to attract souls of the dead to the offerings.

Toys are brought for dead children (los angelitos, or “the little angels”), and bottles of tequila, mezcal or pulque or jars of atole for adults. Families will also offer trinkets or the deceased’s favorite candies on the grave. Some families have ofrendas in homes, usually with foods such as candied pumpkin, pan de muerto (“bread of dead”), and sugar skulls; and beverages such as atole. The ofrendas are left out in the homes as a welcoming gesture for the deceased. Some people believe the spirits of the dead eat the “spiritual essence” of the ofrendas food, so though the celebrators eat the food after the festivities, they believe it lacks nutritional value. Pillows and blankets are left out so the deceased can rest after their long journey. In some parts of Mexico, such as the towns of Mixquic, Pátzcuaro and Janitzio, people spend all night beside the graves of their relatives. In many places people have picnics at the grave site, as well.

Families tidying and decorating graves at a cemetery in Almoloya del Río in the State of Mexico

Some families build altars or small shrines in their homes; these sometimes feature a Christian cross, statues or pictures of the Blessed Virgin Mary, pictures of deceased relatives and other persons, scores of candles, and an ofrenda. Traditionally, families spend some time around the altar, praying and telling anecdotes about the deceased. In some locations, celebrants wear shells on their clothing, so when they dance, the noise will wake up the dead; some will also dress up as the deceased.

Public schools at all levels build altars with ofrendas, usually omitting the religious symbols. Government offices usually have at least a small altar, as this holiday is seen as important to the Mexican heritage.

Those with a distinctive talent for writing sometimes create short poems, called calaveras (skulls), mocking epitaphs of friends, describing interesting habits and attitudes or funny anecdotes. This custom originated in the 18th or 19th century, after a newspaper published a poem narrating a dream of a cemetery in the future, “and all of us were dead”, proceeding to read the tombstones. Newspapers dedicate calaveras to public figures, with cartoons of skeletons in the style of the famous calaveras of José Guadalupe Posada, a Mexican illustrator. Theatrical presentations of Don Juan Tenorio by José Zorrilla (1817–1893) are also traditional on this day.

Modern representations of Catrina

José Guadalupe Posada created a famous print of a figure he called La Calavera Catrina (“The Elegant Skull”) as a parody of a Mexican upper-class female. Posada’s striking image of a costumed female with a skeleton face has become associated with the Day of the Dead, and Catrina figures often are a prominent part of modern Day of the Dead observances.

A common symbol of the holiday is the skull (in Spanish calavera), which celebrants represent in masks, called calacas (colloquial term for skeleton), and foods such as sugar or chocolate skulls, which are inscribed with the name of the recipient on the forehead. Sugar skulls can be given as gifts to both the living and the dead. Other holiday foods include pan de muerto, a sweet egg bread made in various shapes from plain rounds to skulls and rabbits, often decorated with white frosting to look like twisted bones.

Part of the “megaofrenda” at UNAM for Day of the Dead

The traditions and activities that take place in celebration of the Day of the Dead are not universal, often varying from town to town. For example, in the town of Pátzcuaro on the Lago de Pátzcuaro in Michoacán, the tradition is very different if the deceased is a child rather than an adult. On November 1 of the year after a child’s death, the godparents set a table in the parents’ home with sweets, fruits, pan de muerto, a cross, a rosary (used to ask the Virgin Mary to pray for them) and candles. This is meant to celebrate the child’s life, in respect and appreciation for the parents. There is also dancing with colorful costumes, often with skull-shaped masks and devil masks in the plaza or garden of the town. At midnight on November 2, the people light candles and ride winged boats called mariposas(butterflies) to Janitzio, an island in the middle of the lake where there is a cemetery, to honor and celebrate the lives of the dead there.

In contrast, the town of Ocotepec, north of Cuernavaca in the State of Morelos, opens its doors to visitors in exchange for veladoras(small wax candles) to show respect for the recently deceased. In return the visitors receive tamales and atole. This is done only by the owners of the house where someone in the household has died in the previous year. Many people of the surrounding areas arrive early to eat for free and enjoy the elaborate altars set up to receive the visitors.

Sculpture with skeletons made for Day of the Dead at the Museo de Arte Popular, Mexico City

In some parts of the country (especially the cities, where in recent years other customs have been displaced) children in costumes roam the streets, knocking on people’s doors for a calaverita, a small gift of candies or money; they also ask passersby for it. This relatively recent custom is similar to that of Halloween’s trick-or-treating in the United States.

Some people believe possessing Day of the Dead items can bring good luck. Many people get tattoos or have dolls of the dead to carry with them. They also clean their houses and prepare the favorite dishes of their deceased loved ones to place upon their altar or ofrenda.