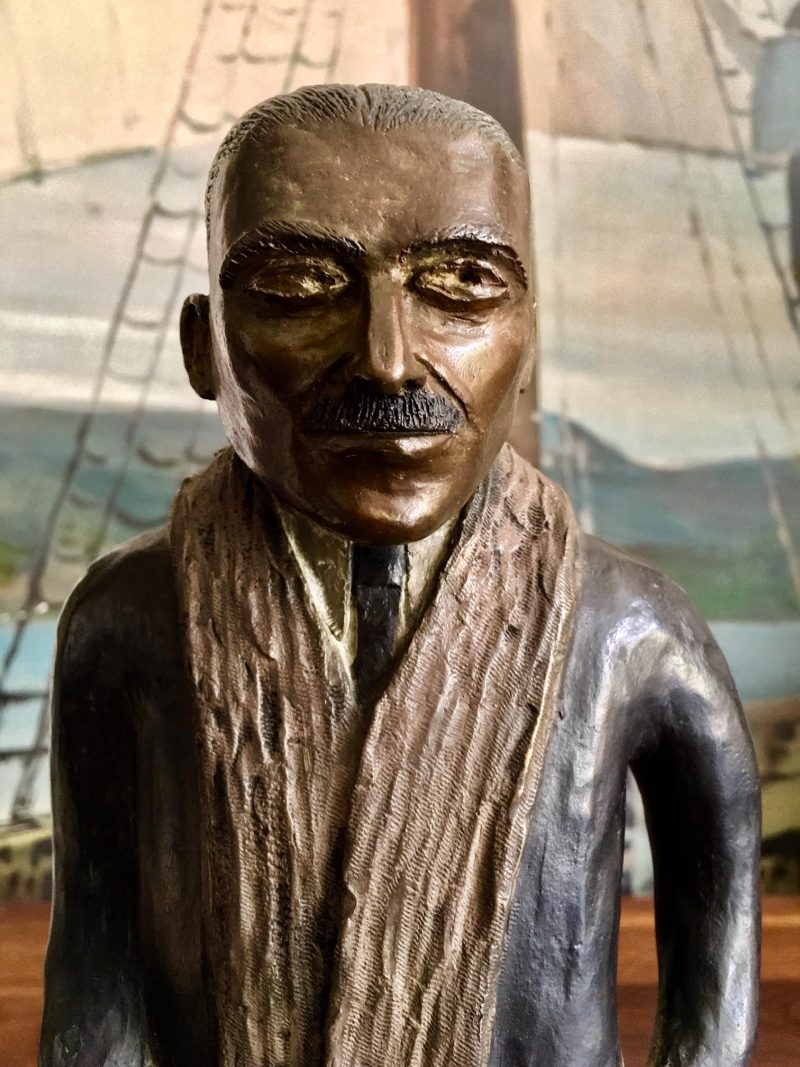

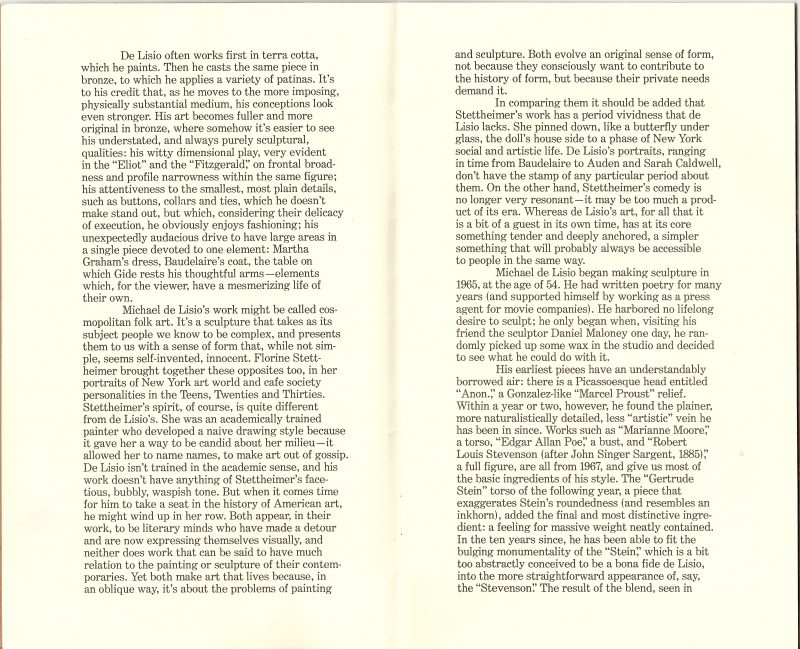

Bronze Sculpture of Charles Demuth, Michael DeLiso, 1981

Michael De Lisio (American 1912-2003), Sculpture Portrait of Charles Demuth (American 1883-1935), multipatinated bronze, Inscribed on base:” de Lisio / 1/6 / C.81″. JM Foundry mark/stamp on the base. Measures 13.25 inches height x 5.25 inches width at base x 3.25 inches depth of sculpture.

Price available upon request.

New York Times Obituary:

Michael de Lisio, 91, Sculptor Who Turned Photos Into Statues

By ROBERTA SMITH February 2, 2003

Michael de Lisio, a sculptor and poet, died on Jan. 21 in Manhattan, one day short of his 92nd birthday.

Mr. de Lisio was born in Manhattan. His parents were Italian immigrants, and he was largely self-taught. He had minor success as a poet, publishing sporadically in little magazines as well as in Scribner’s and The New Yorker.

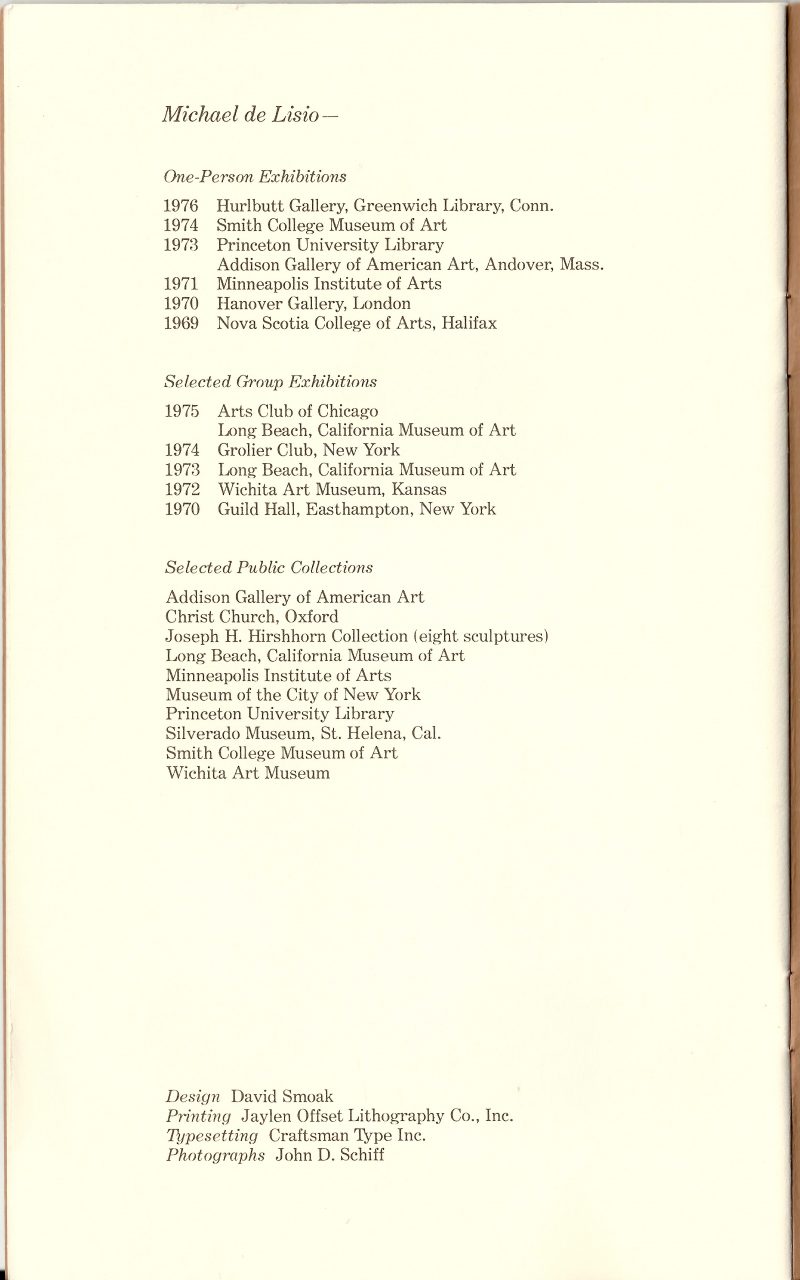

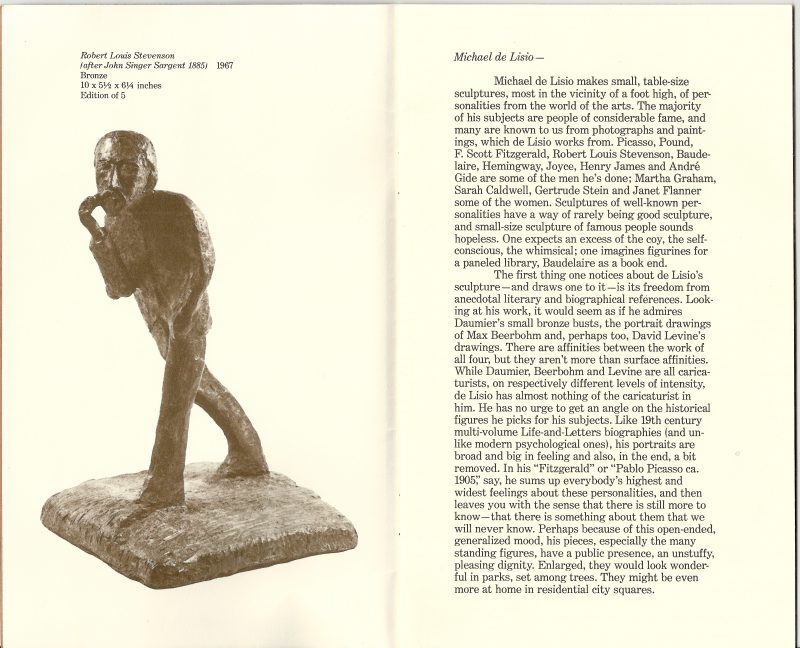

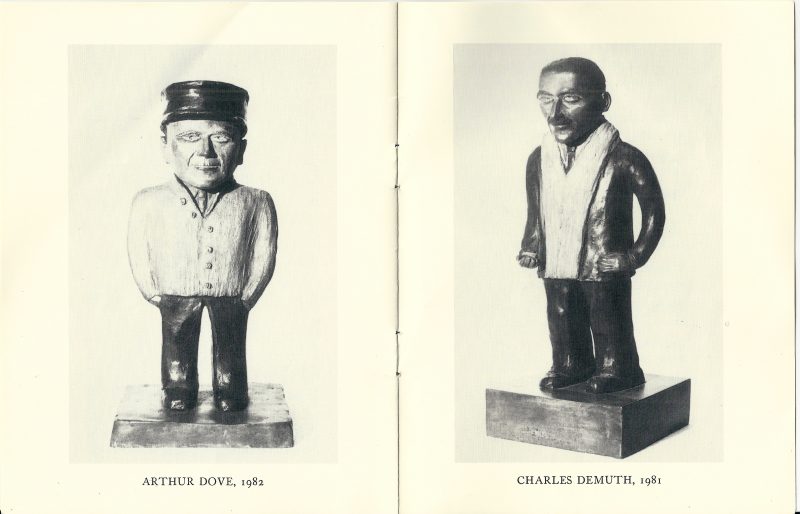

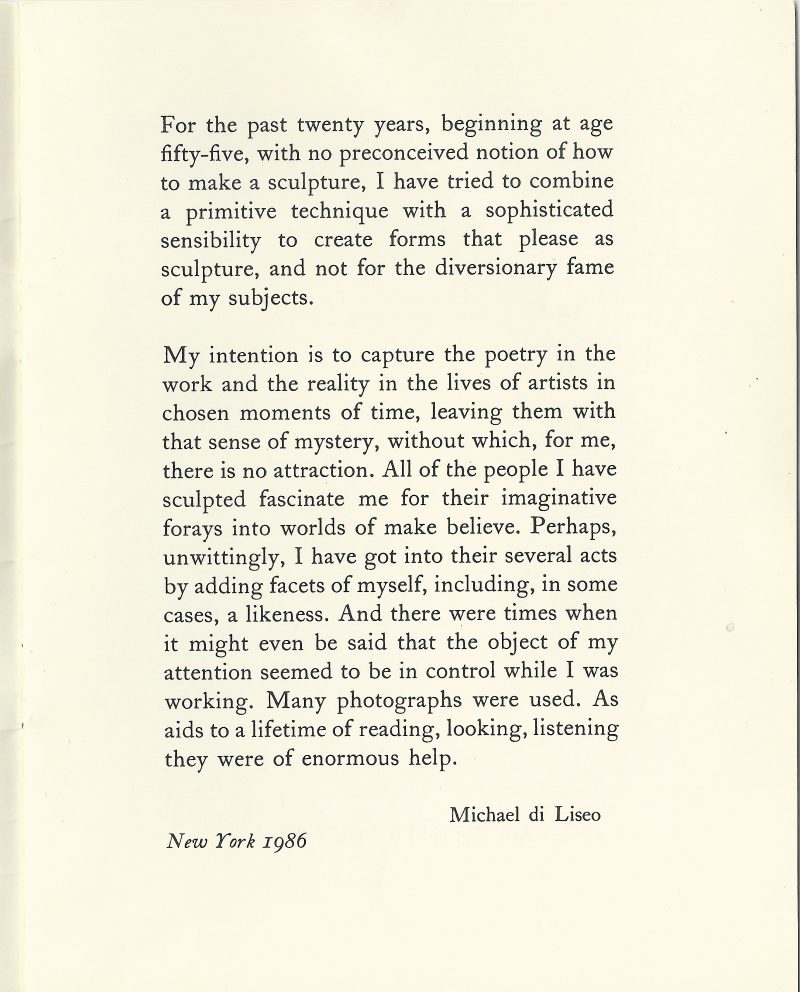

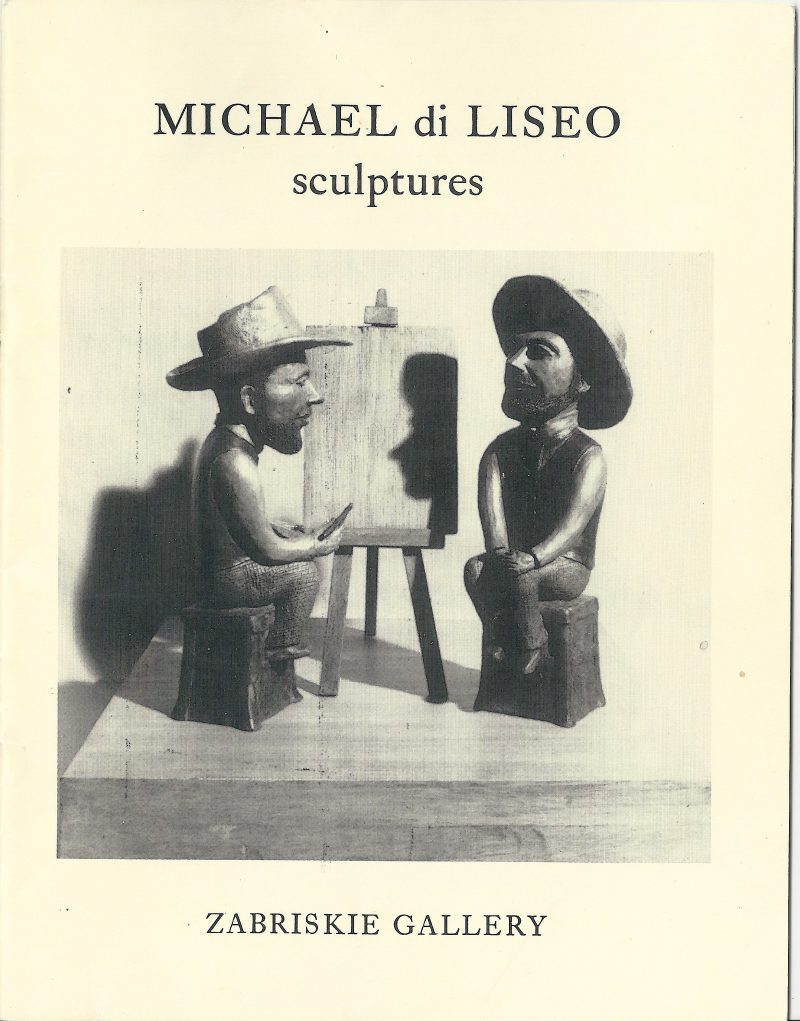

After serving in the United States Navy during World War II, he worked for two decades in public relations, mostly for MGM. In 1965, at 54, he turned to sculpture. Working in painted terra cotta as well as in bronze, he began making small, seemingly quaint yet psychologically telling portraits of the writers and artists he admired and sometimes knew personally.

His depictions usually took well-known photographs startlingly into three dimensions, like Barbara Morgan’s famous 1940 image of Martha Graham with her torso pitched forward and her long gown sweeping upward like an open fan.

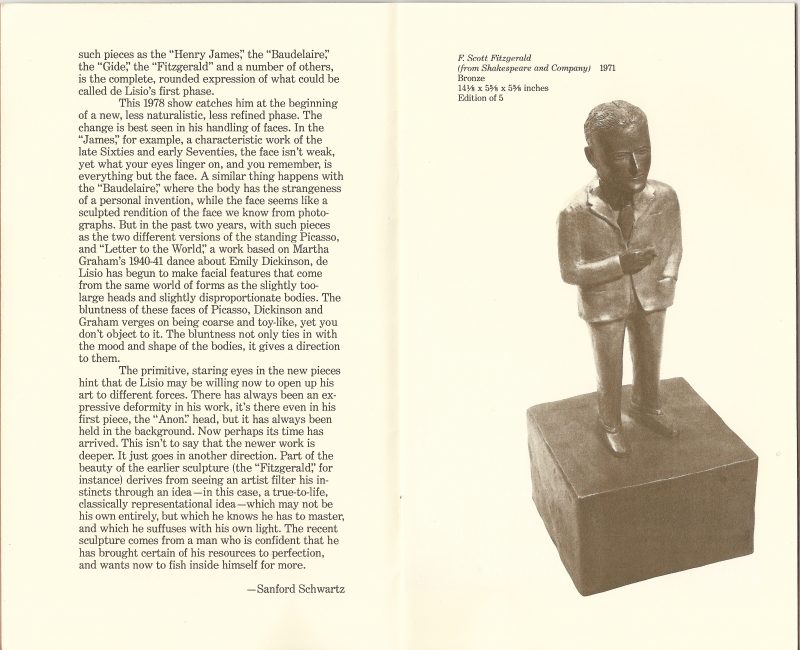

Other subjects included W. H. Auden, Janet Flanner, Truman Capote and Virgil Thomson, who were friends, as well as Emily Dickinson, Henry James, Marsden Hartley, Alfred Stieglitz and Toulouse-Lautrec. He also made a group portrait of Sylvia Beach and writers who congregated at her bookshop, Shakespeare & Company, in Paris in the 1920’s and 30’s.Mr. de Lisio had solo shows at the Nova Scotia College of Art in Halifax (1969); the Minneapolis Institute of Arts (1971); the Addison Gallery of American Art in Andover, Mass. (1973); and the Smith College Museum of Art in Northampton, Mass. (1974 and 1980).

He had New York gallery shows at Brooke Alexander in 1978 and Zabriskie in 1986 and a retrospective at Boston College in 1998. His works are in the collections of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, the Addison Gallery, Boston College and the Smith College Museum of Art.

Mr. de Lisio’s companion, the journalist, editor and collector Irving Drutman, died in 1978.

Because of failing eyesight, Mr. de Lisio returned to poetry in his last decade, working in a style as understated and compressed as his sculpture:

“The charisma of 90

can be undone

by slowly becoming

91″.

www.nytimes.com/2003/02/02/nyregion/michael-de-lisio-91-sculptor-who-turned-photos-into-statues.html

https://www.bc.edu/sites/artmuseum/exhibitions/artlit/

Auction results: https://auctions.stairgalleries.com/lot/michael-delisio-1911-2003-portrait-of-virgil-thomson-3902101

Charles Henry Buckius Demuth (November 8, 1883 – October 23, 1935) was an American watercolorist who turned to oils late in his career, developing a style of painting known as Precisionism.

“Search the history of American art,” wrote Ken Johnson in The New York Times, “and you will discover few watercolors more beautiful than those of Charles Demuth. Combining exacting botanical observation and loosely Cubist abstraction, his watercolors of flowers, fruit and vegetables have a magical liveliness and an almost shocking sensuousness.”[

Demuth was a lifelong resident of Lancaster, Pennsylvania. The home he shared with his mother is now the Demuth Museum, which showcases his work. He graduated from Franklin & Marshall Academy before studying at Drexel University and at Philadelphia‘s Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. While he was a student at PAFA, he participated in a show at the Academy, and also met William Carlos Williams at his boarding house. The two were fast friends and remained close for the rest of their lives.

He later studied at Académie Colarossi and Académie Julian in Paris, where he became a part of the avant garde art scene. The Parisian artistic community was accepting of Demuth’s homosexuality. After his return to America, Demuth retained aspects of Cubism in many of his works.

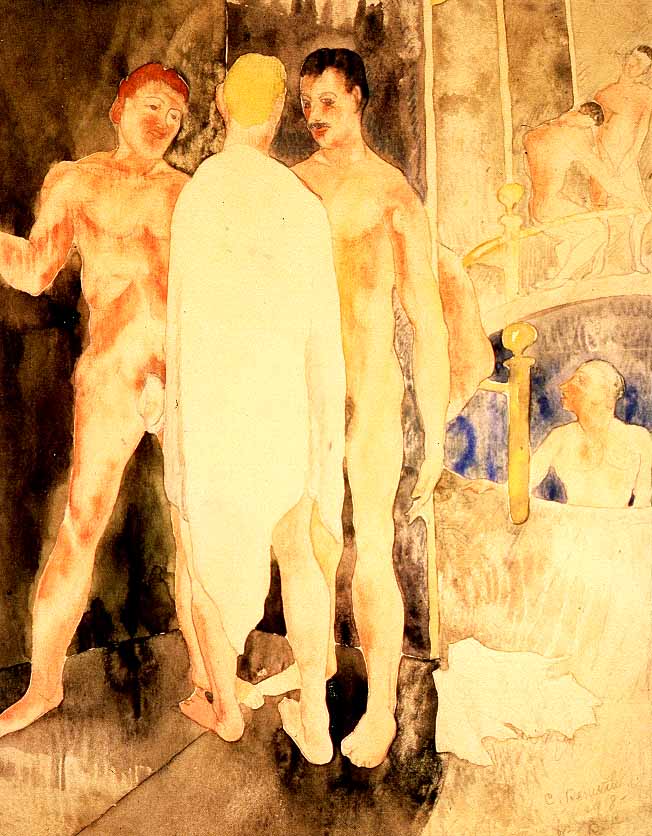

Demuth, who was himself a gay artist, was a regular patron at the Lafayette Baths. His sexual exploits there are the subject of watercolors, including his 1918 homoerotic self-portrait set in a Turkish bathhouse.[

Demuth spent most of his life in frail health. By 1920, the effects of diabetes had begun to severely drain Demuth of artistic energy. He died at his residence in Lancaster at the age 51 of complications from diabetes. He is buried at the Lancaster Cemetery.

Born in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, Charles Demuth moved with his family to the 18th century brick row home on East King Street at the age of 6. Here, in his home and studio, Demuth created over 1,000 artworks, many of which were inspired by the people, places, and things he encountered in his hometown.

Demuth traveled extensively and his art was energized by his experiences. As an artist and a gay man in the early 20th century, Demuth’s social and professional circles included that of the avant-garde art and queer communities.

Demuth’s creativity abounded in various forms and he became a master watercolorist. However, some of his most significant contributions to art history were painted in other mediums. These include Precisionist paintings, adaptated from Cubism principles, and Poster Portraits layered with symbolism.

Charles Demuth’s legacy as a pioneer in American Modernism continues to captivate and inspire today.

View Video Transcript (English) (PDF) | Transcripción de Vídeo (Español) (PDF)

Demuth Museum Reinterpretation Project

INTRODUCTION

Now over 40-years-old, the Demuth Foundation has done tremendous work to preserve and promote the legacy of Modernist painter Charles Demuth (1883-1935) in Lancaster, PA. The Foundation started as a grassroots effort to convert the artist’s home and studio into a museum in the early 1980s, and today boasts the largest collection of his work, attracts audiences from across the globe, and is a member of the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s Historic Artists’ Home and Studio program.

In 2022, the Foundation began work to incorporate unaddressed or underrepresented themes within its interpretation of Charles Demuth and our historic site. Our audiences’ appetite for more information and deeper engagement is growing, and we want to meet their enthusiasm and provide more content to discuss Demuth and his work more fully. Previous interpretation at our Museum has included Demuth’s influence on American Art, his colleagues and peers in the Modern Art movement, and 19th and early 20th century life in Lancaster. Foundation publications have emphasized Demuth’s relationships (Charles Demuth and Friends, 2003) and his travels (Out of the Chateau, 2007). This is a look into the personhood of Charles Demuth—his personality, his lifestyle, the traits that influenced his life and work.

With funding from the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s Telling the Full History Preservation Fund, with support from the National Endowment for the Humanities, we embarked on a research project to explore the themes of Demuth’s relationship to the LGBTQ+ community of his time and how disability and disease may have impacted his artwork. It is important to note that this is not the first time these topics have been discussed, but this is the first formal inquiry and report by the Foundation in these areas. It is also imperative to state that this work is an ongoing process as we get to know Charles Demuth more fully.

Our methodology for this research project emphasized bringing outside expert voices to the table to discuss and present their findings and analysis. An independent public historian and researcher, Dr. Susan Ferentinos, was contracted to prepare a report answering the following questions:

- What did a homosexual lifestyle look like for early 20th century artists in America? How did queer culture manifest and vary in communities that Charles Demuth lived in or visited?

- What evidence exists to support the assumption that Charles Demuth was gay? Is there documentation that would support or discredit this claim?

We also invited 10 art scholars and curators from across the country to contribute an essay that analyzes one of Demuth’s works of art. Five responded affirmatively and have submitted articles that highlight a variety of Demuth’s work through fresh lenses. They were asked to select one of Charles Demuth’s pieces and draft a short essay conveying their interpretation and analysis of the work and how his sexuality or disability may have impacted the piece. We’ve also invited Franklin & Marshall College American Studies and Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies professor Alison Kibler to share some of her findings on Lancaster vice and the environments Charles Demuth would have encountered while “in the Province.”

At the onset of our project, we partnered with the YWCA of Lancaster for a gender and sexuality training and discussion on the ethics of posthumously “outing” historic figures. The YWCA has also reviewed our compiled research and offered a local perspective for our reinterpretation project.

In addition, staff has done a significant amount of reading and research to inform and guide our project. A list of those resources is included in this document.

The following is a compilation of our acquired research from April 2022 through March 2023. This information will inform the next steps of our reinterpretation at the Demuth Museum.

Abby Baer

Executive Director, Demuth Foundation

RESEARCH COMPILATION

Click on the thumbnails or links beneath the thumbnails to read or download the essays. Essays will download in a PDF format.