Collection of ‘Shroud of Turin’ Mid Century Photographs & Art Historian Notes

Verbally Appraised at USD$3500 / Sold only as a set.

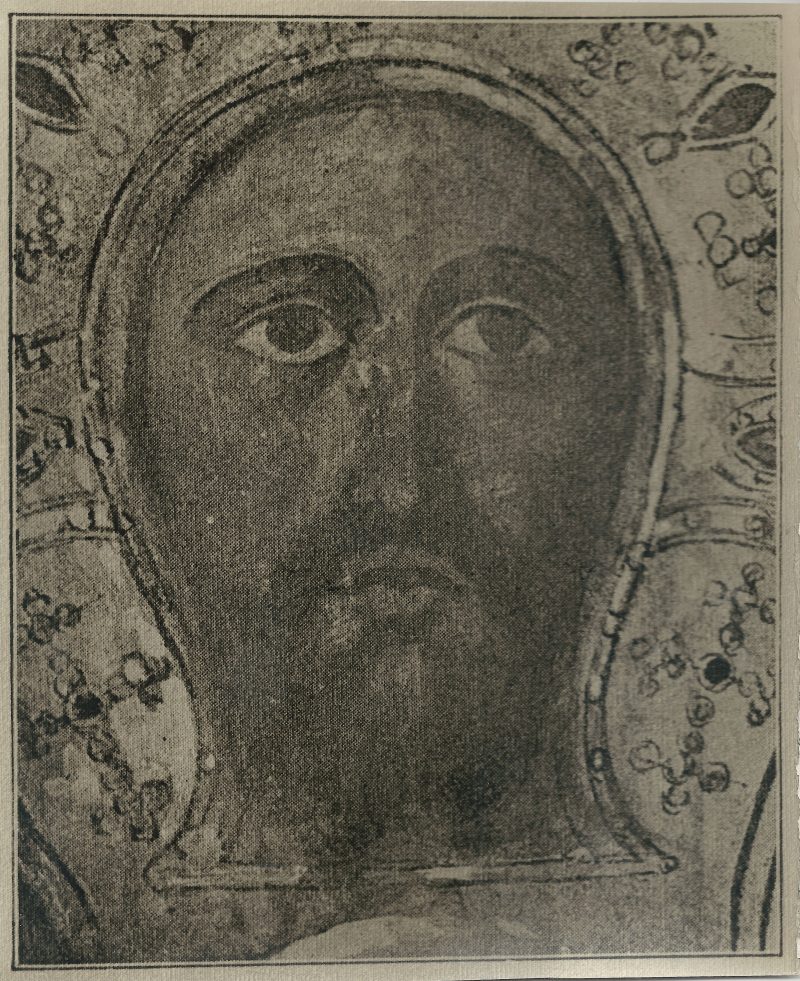

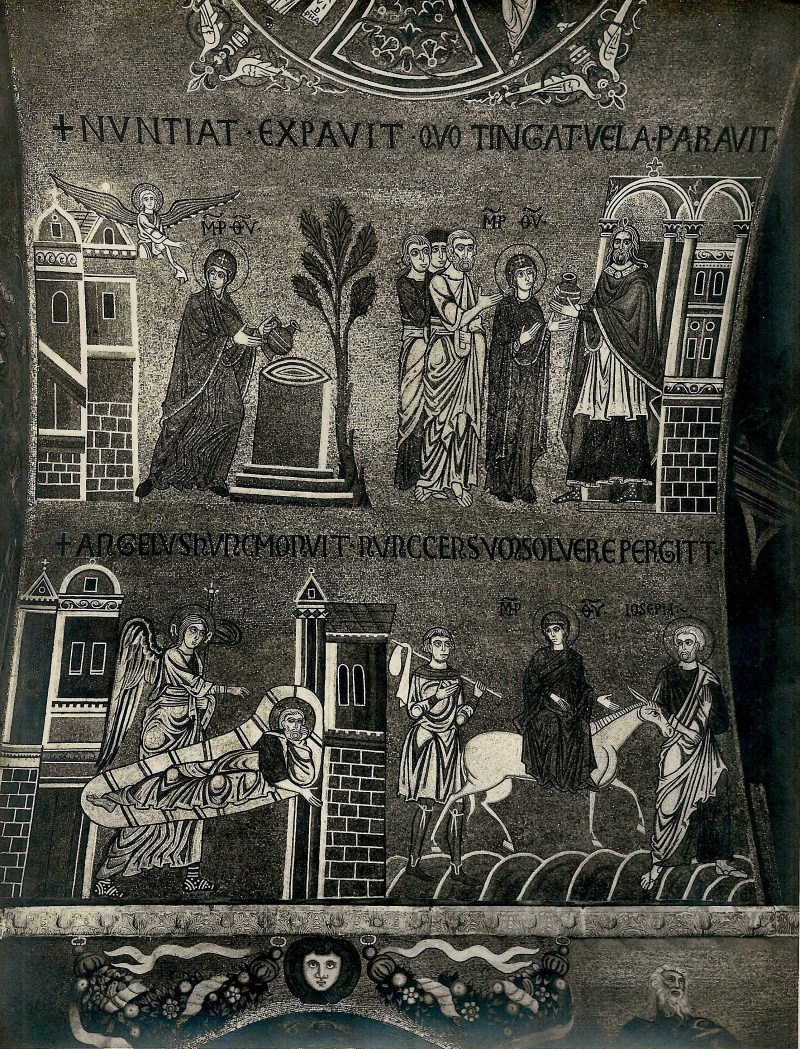

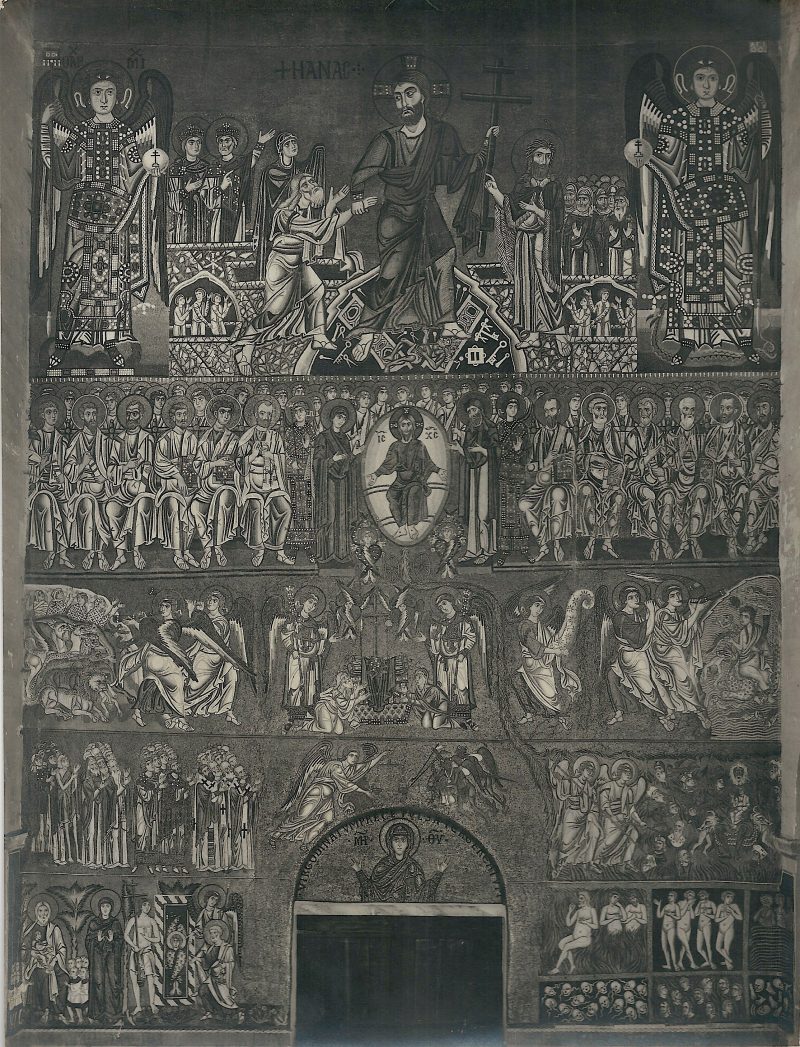

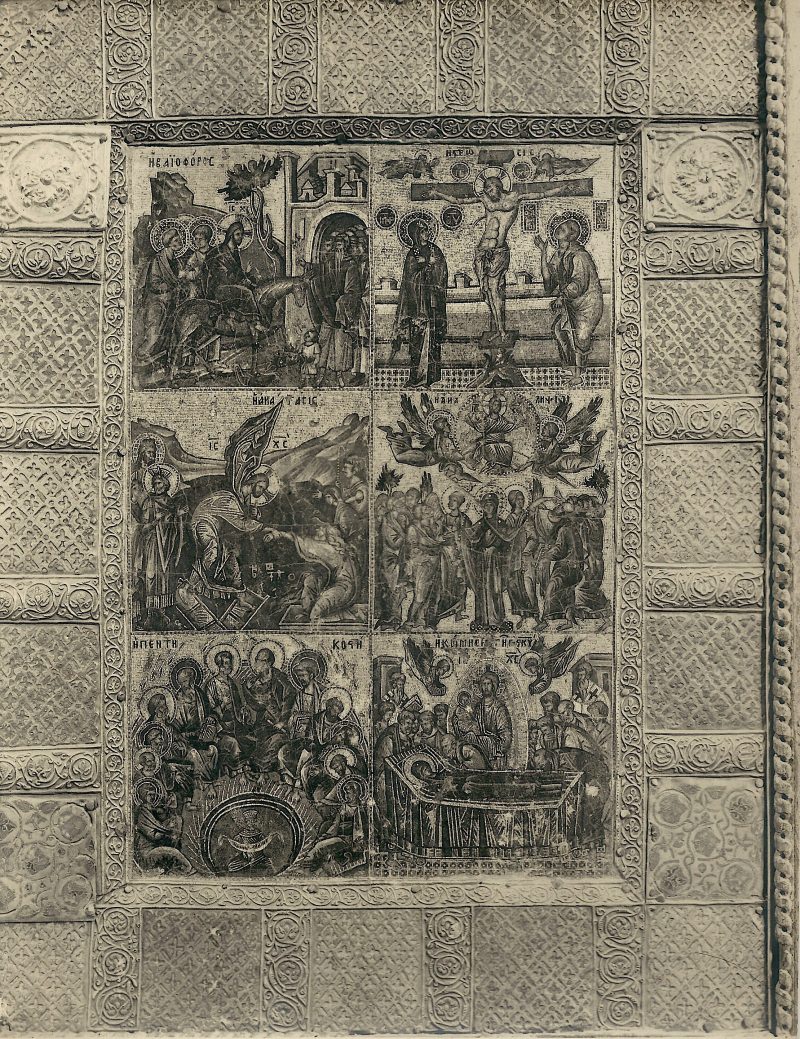

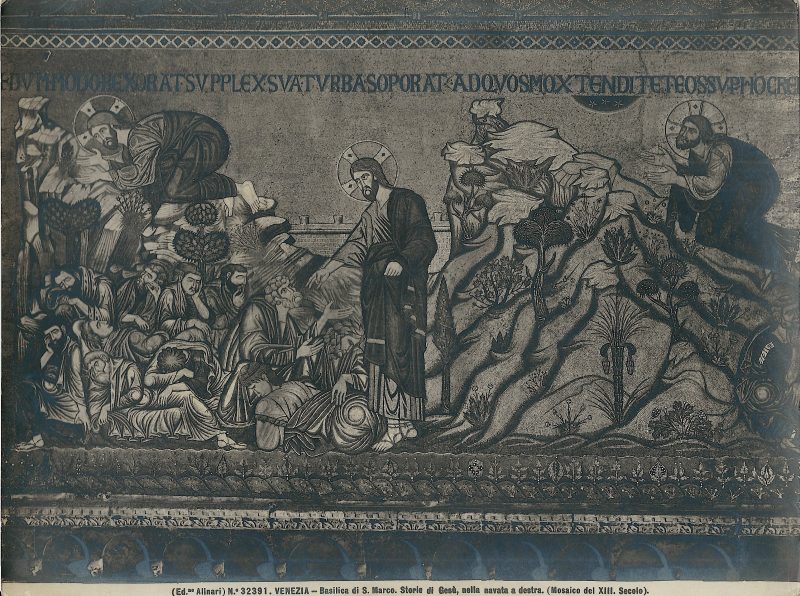

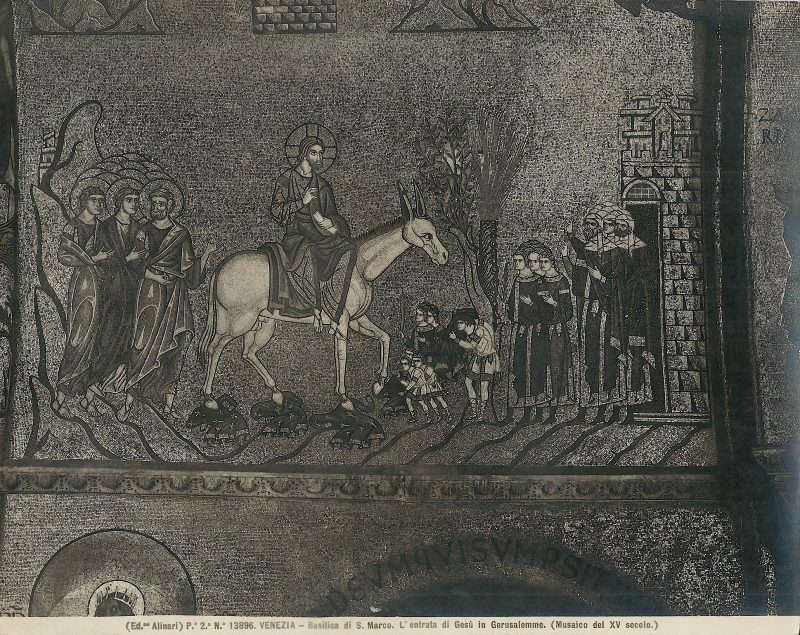

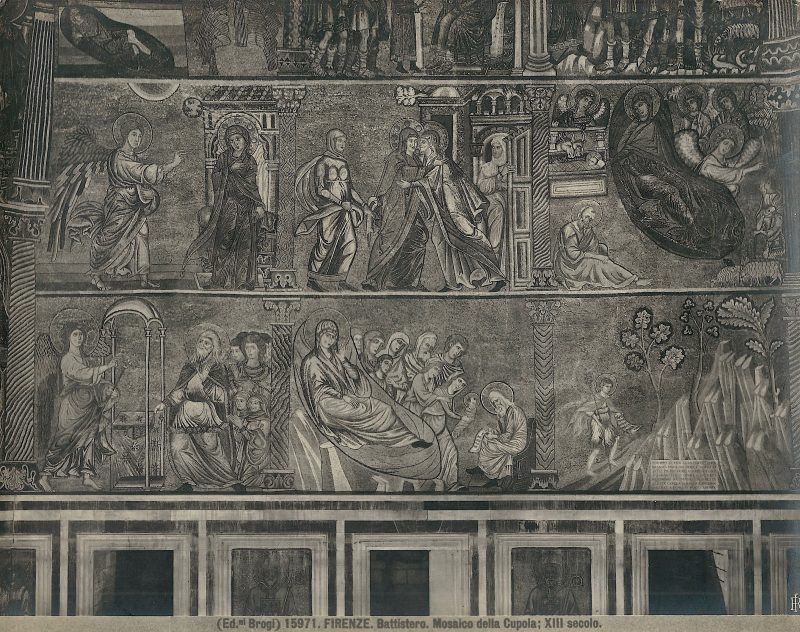

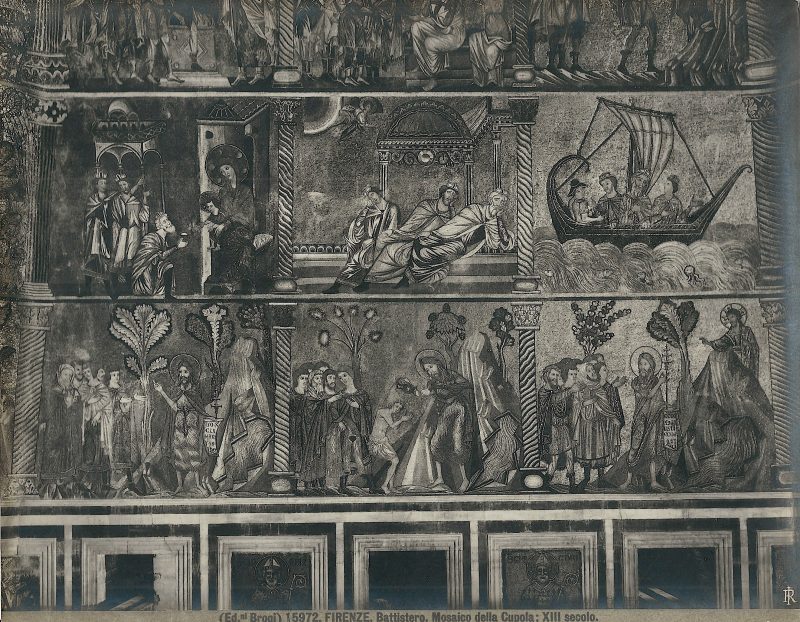

(Images of ‘Life of Christ’ mosaics are sold seperately / ask for info)

Update: 13 of the images/photos have been sold at auction (as a set).

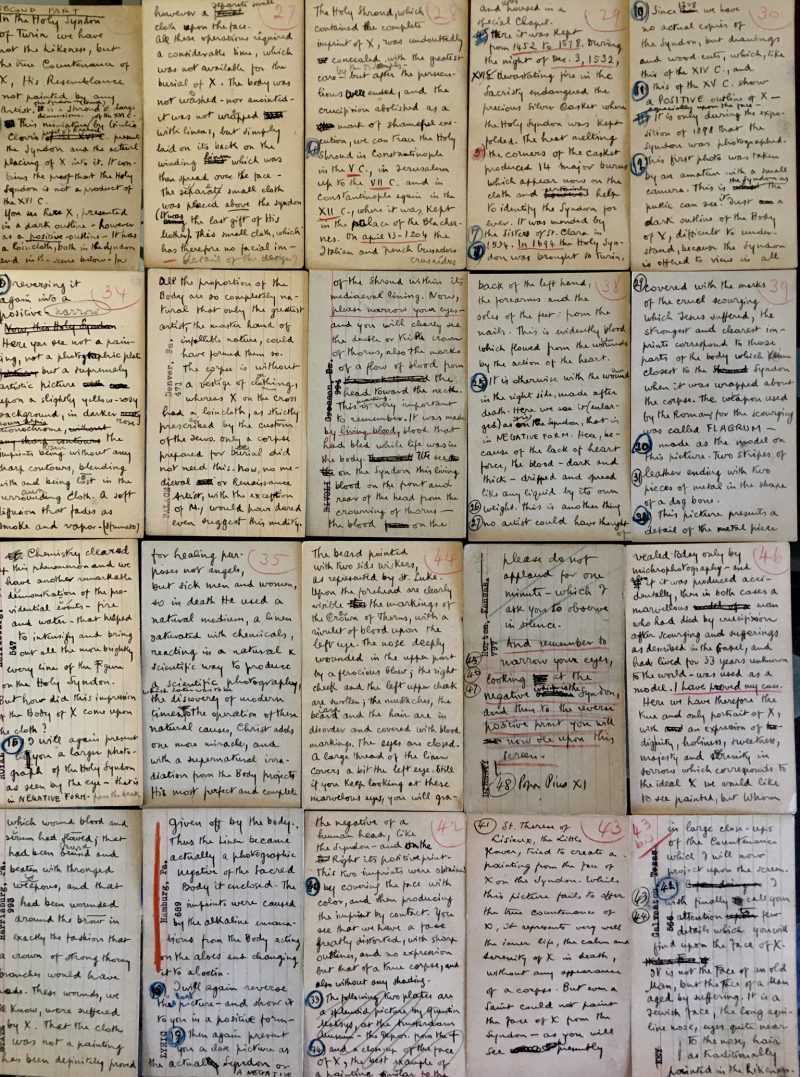

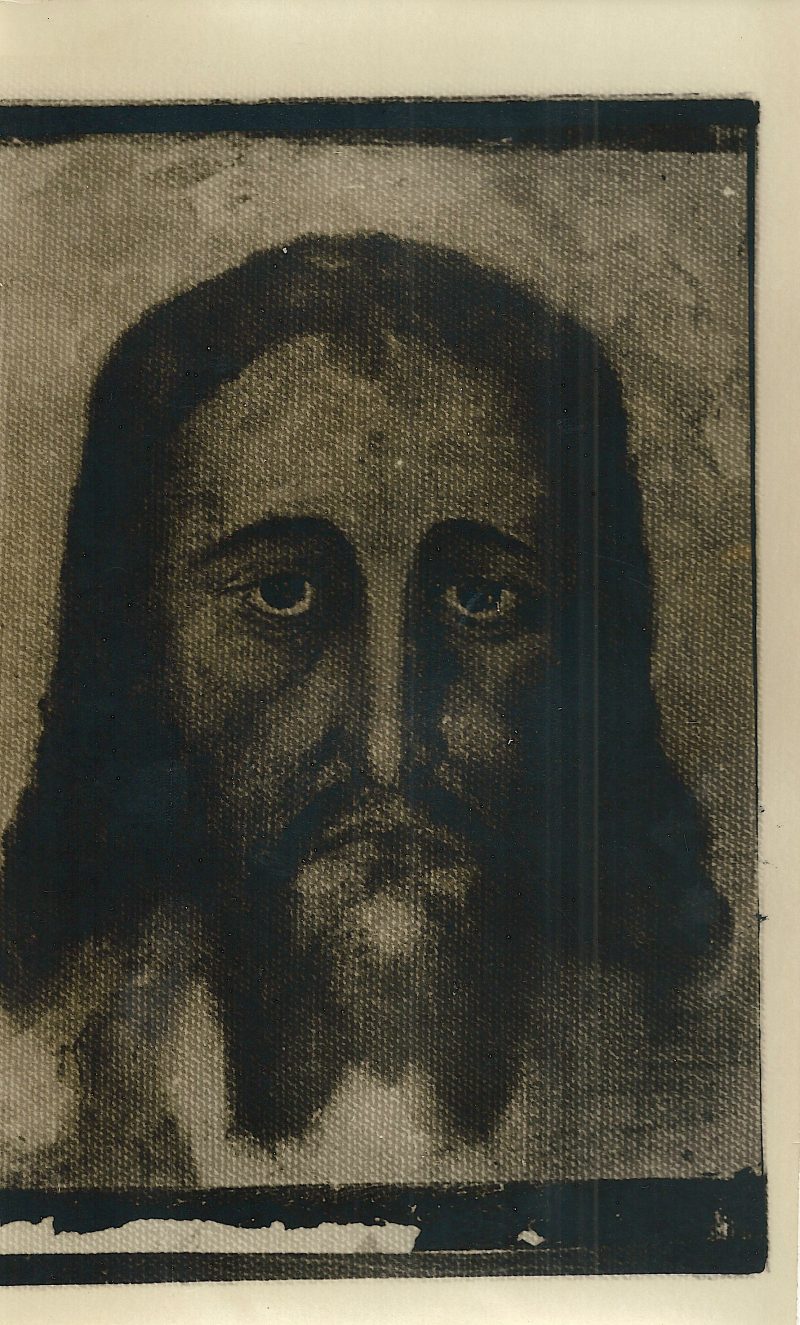

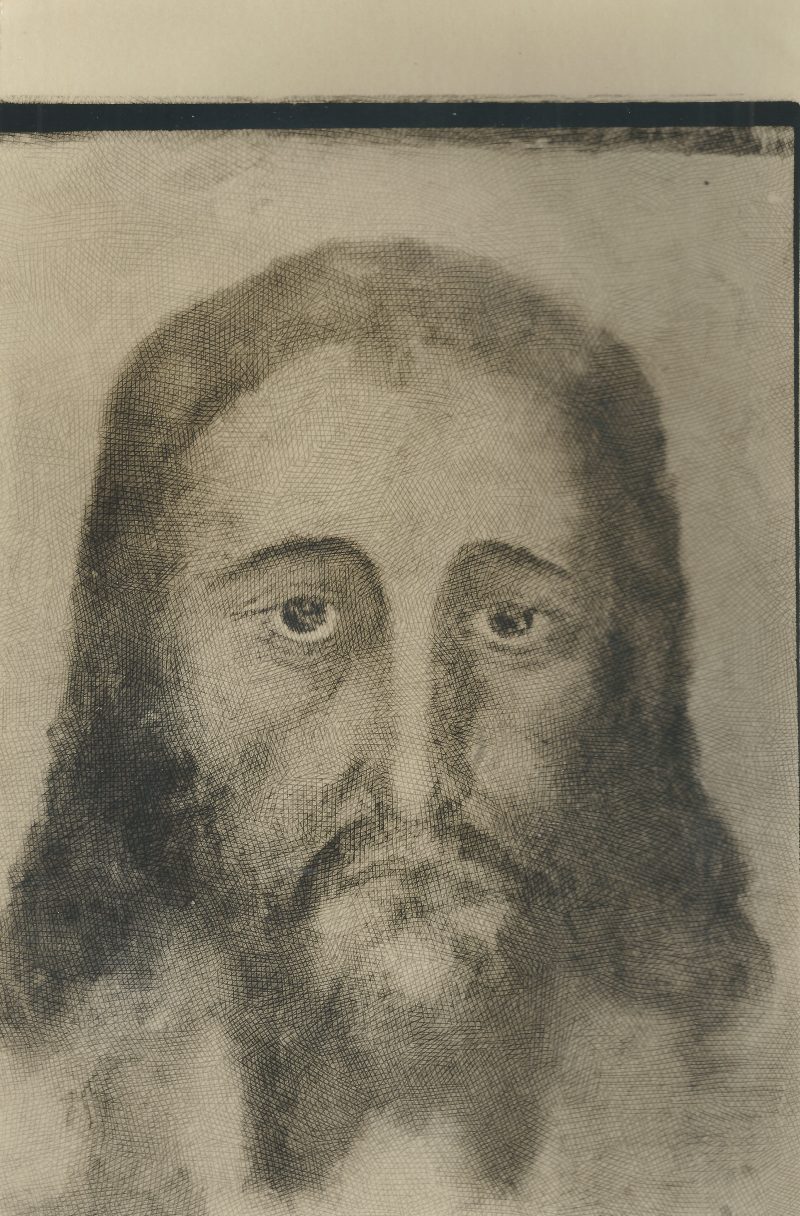

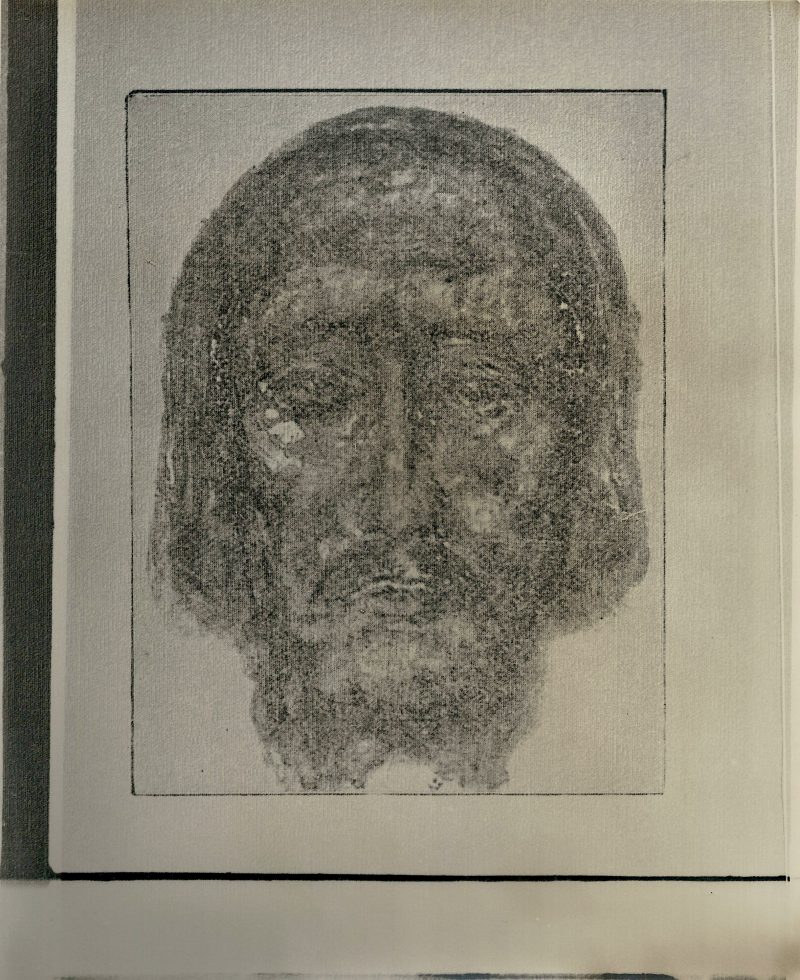

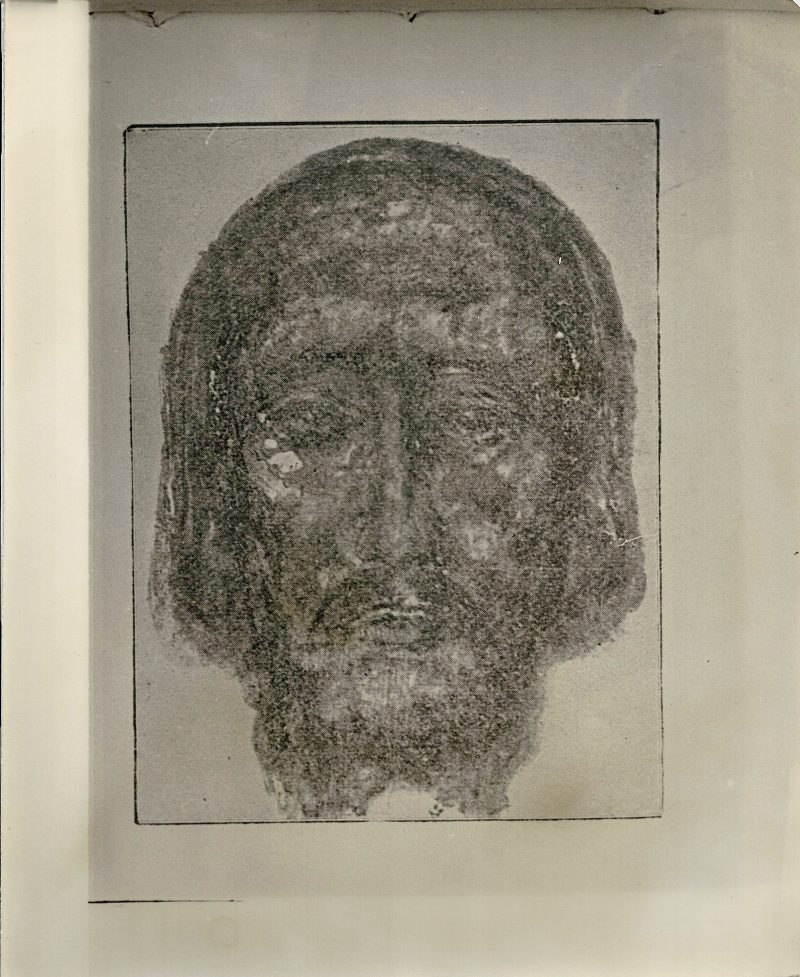

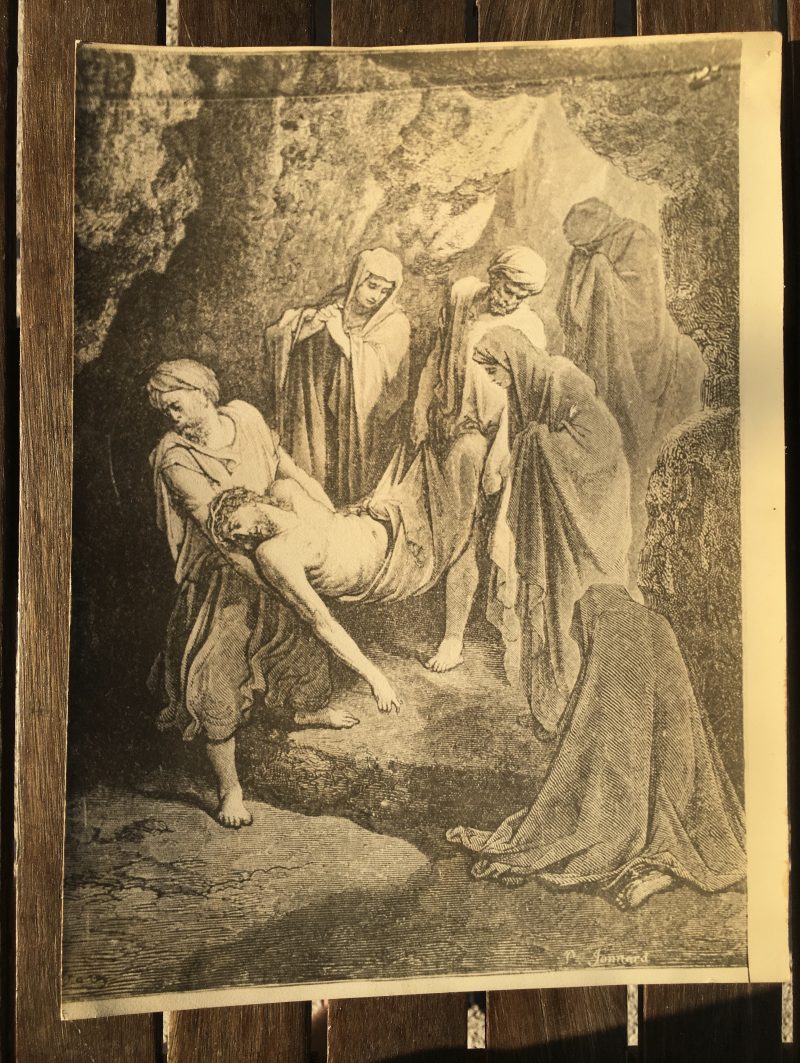

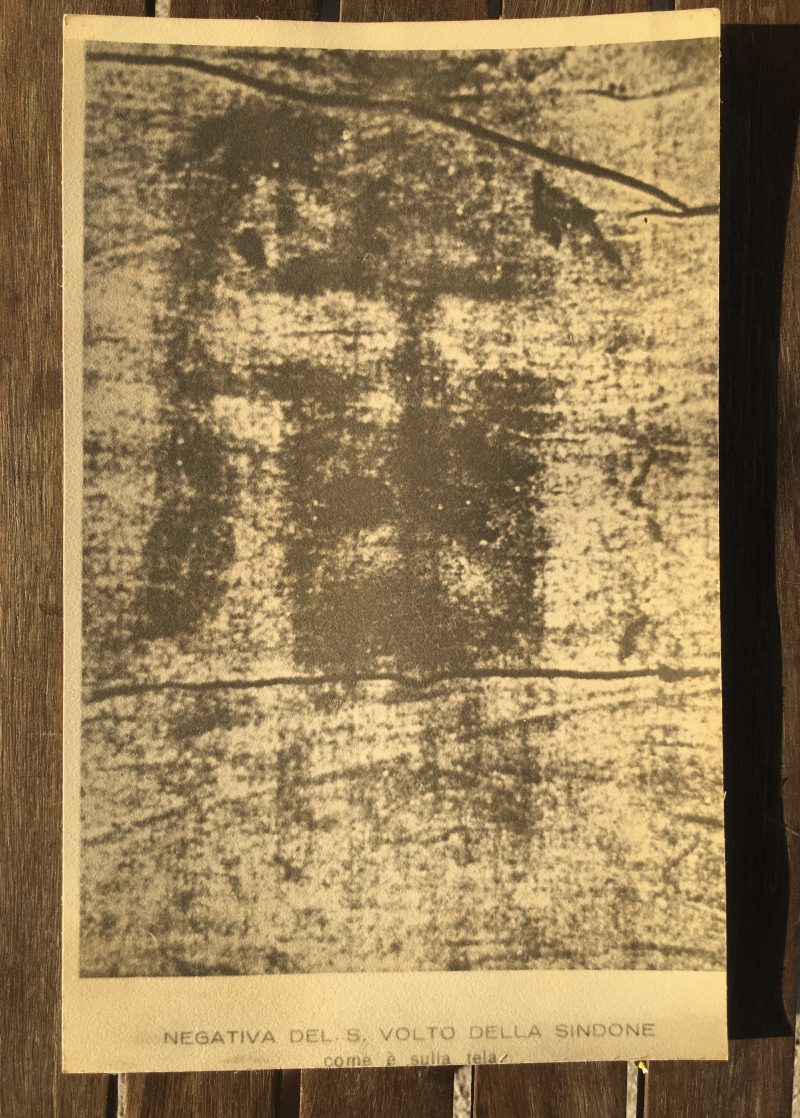

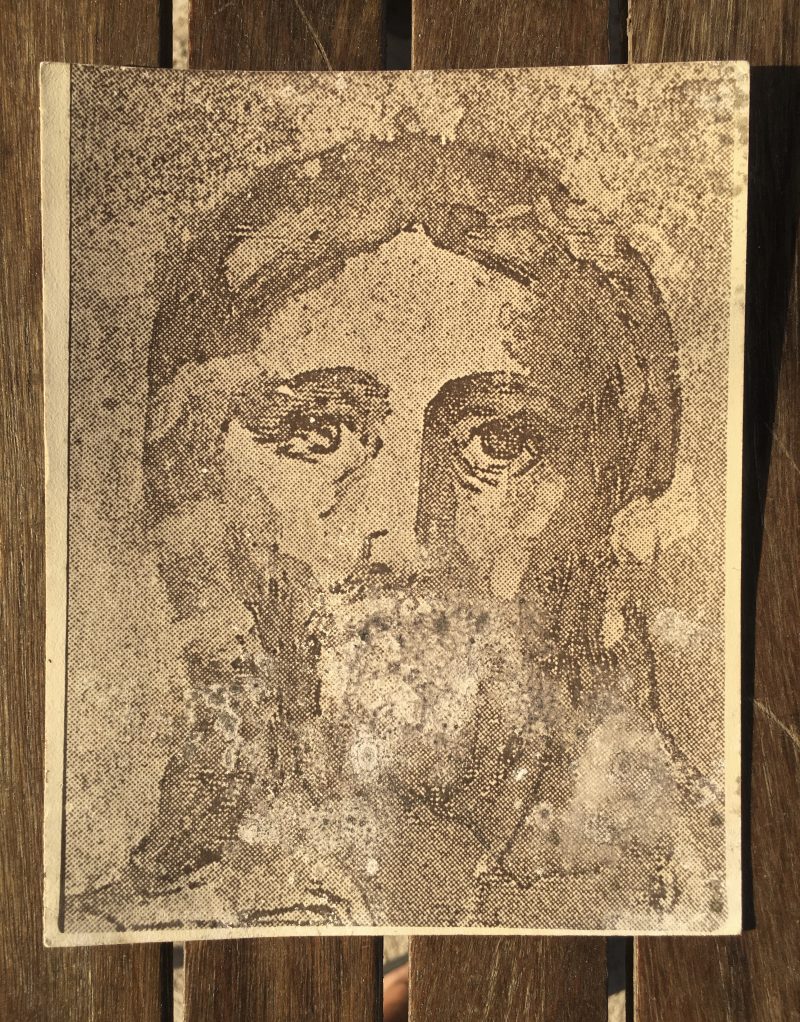

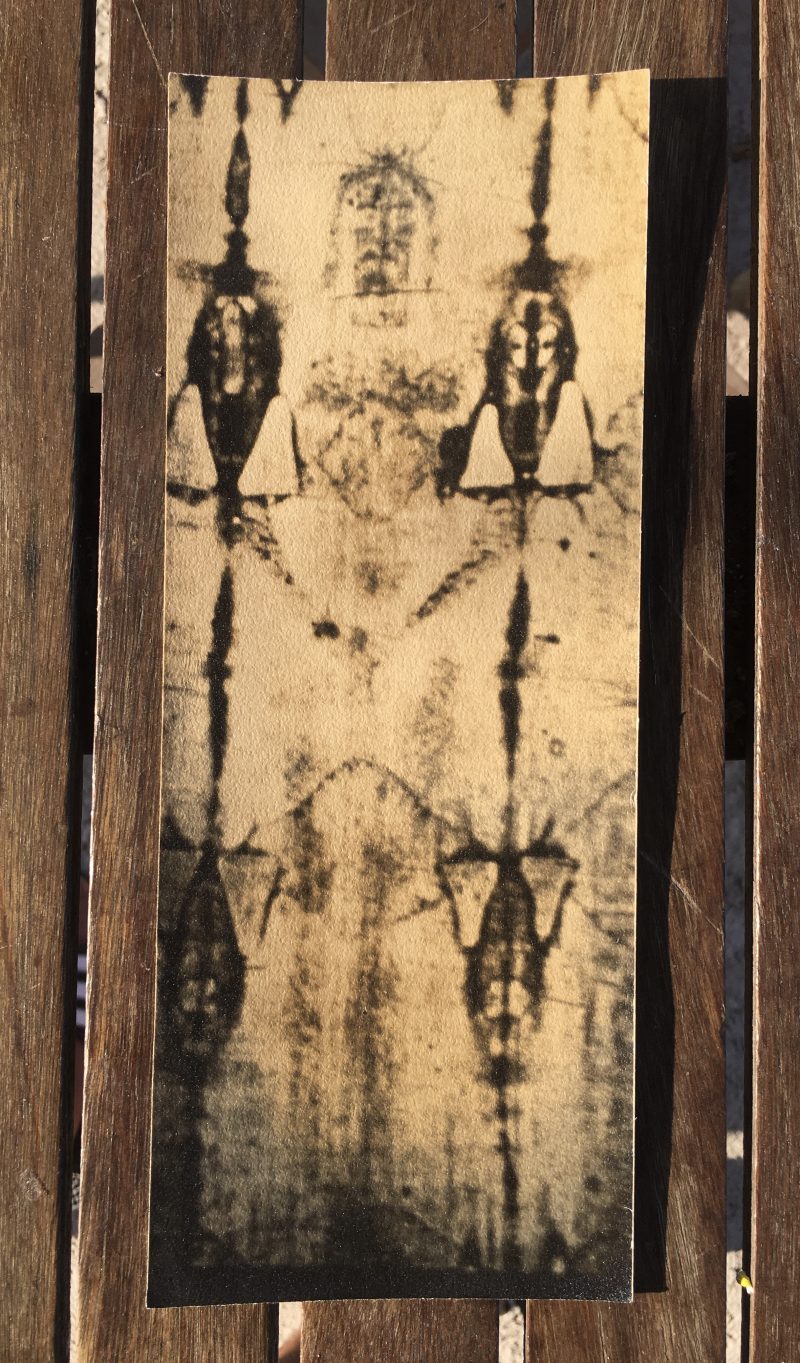

Collection of ‘Shroud of Turin’ Mid Century Historical Photographs & Art Historian Notes. A very particualr & rare find. I deduct, along with the provenance seen below, that these are the hand written notes and historical photograhs which were used for an art history talk, or even a religious based public talk on the origin & history of the ‘Shroud of Turin’. What is fascinating is the collection of photographs that were printed individually from public archives, to be able to present the images ‘auditorium style’ setting, I presume with a type of projector normally used to display any photo image onto a wall. A very elaborate and complex way to do a visual history discussion, hopefully with the help of an assistant.

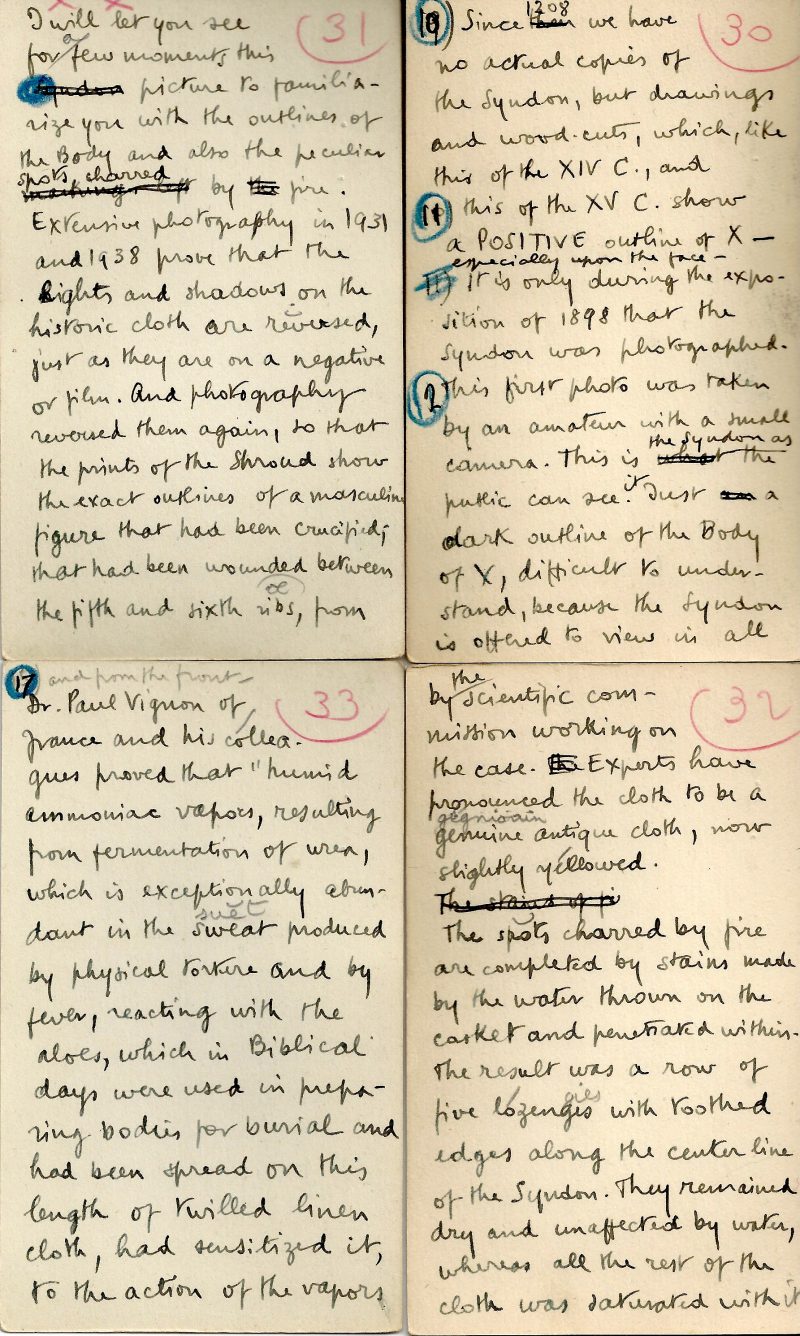

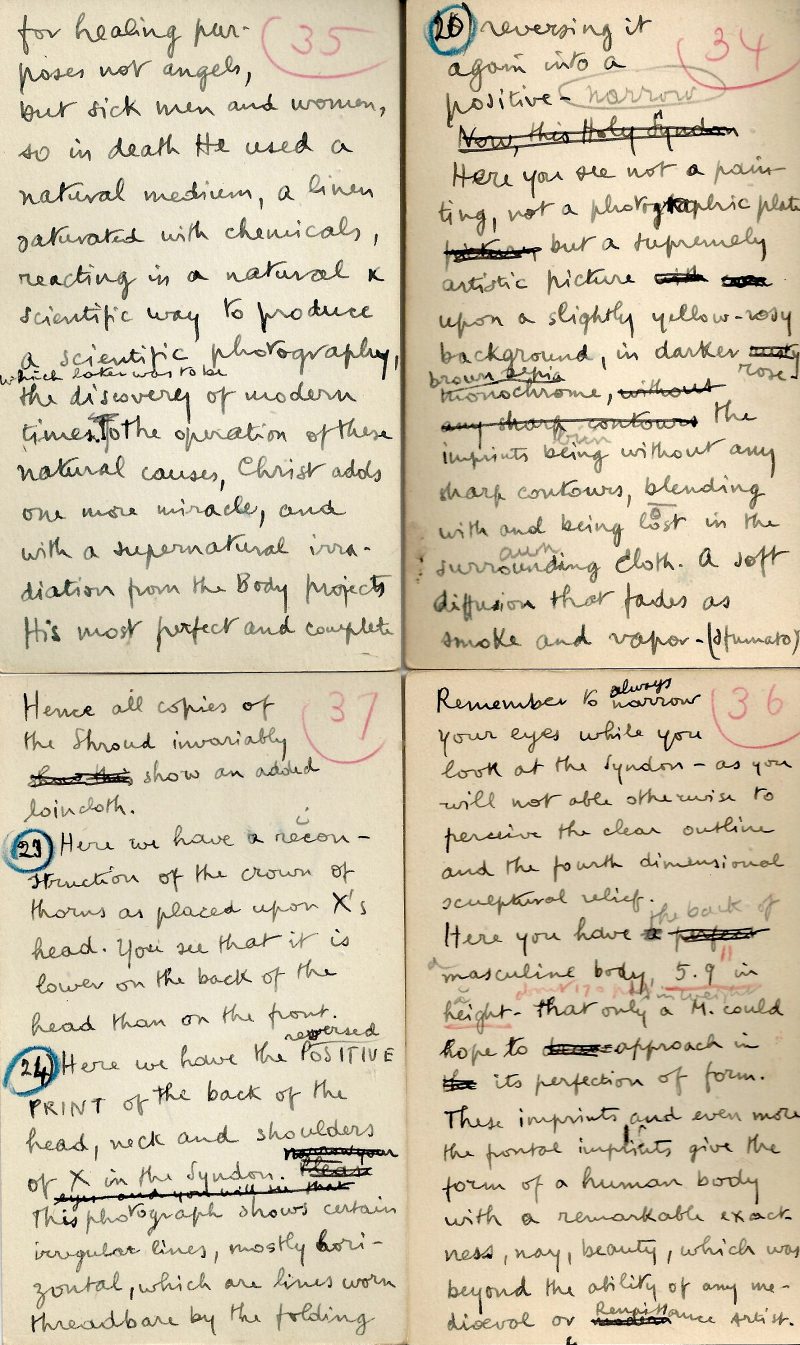

Collection contains 24 (one blank) hand written, double-sided note cards used for the history talk, written on former used ‘index cards’ measuring 3 x 5 inches (the type of cards used to keep contacts, names, addresses, in a small box). The cards seem to be part 2 of a set used for the talk. (Part one is missing). Cards are numbered, to know it’s proper order for reading.

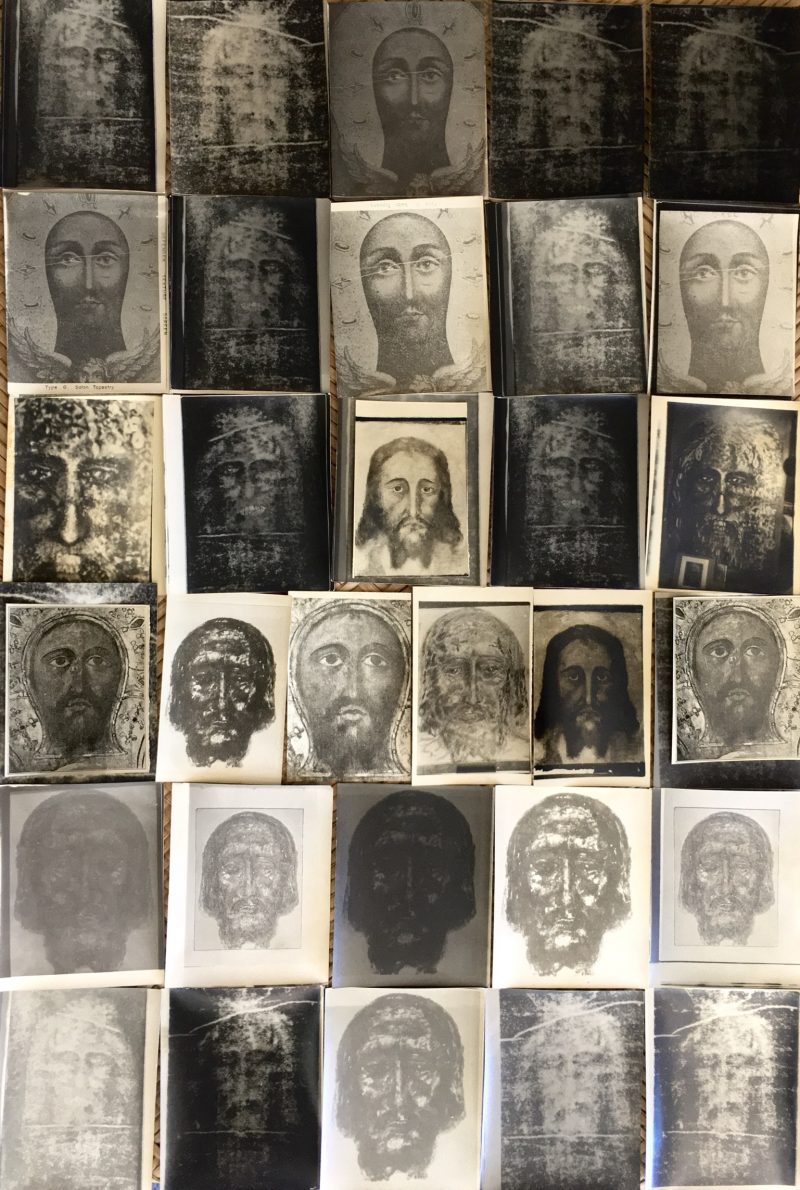

Also contains a large number of reference photographs, which are all actual authentic, dark room printed, silver gelatin prints, varying in size from smallest at 6 x 9 inches (7 prints) to 8 x 10 inches (31 prints) for a total of 45 photos. Update: Ive recently returned and found 7 more authentic photos from the same series.

New total of authentic photographs is now 45. (minus 13 sold at auction)

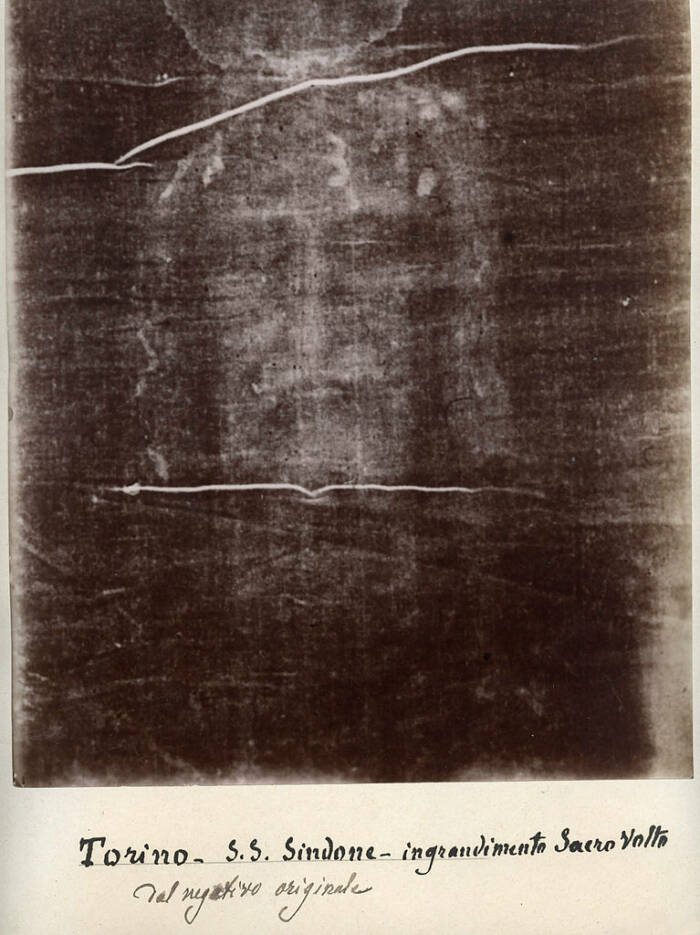

I conclude that the photographs were taken by using a large format camera, and images were photographed directly from art history books, and then, were prints in darkroom, as seen by the information on the edges of the photographs, & by the handwritting in graphite pencil, brief notations on the verso of some of the prints.

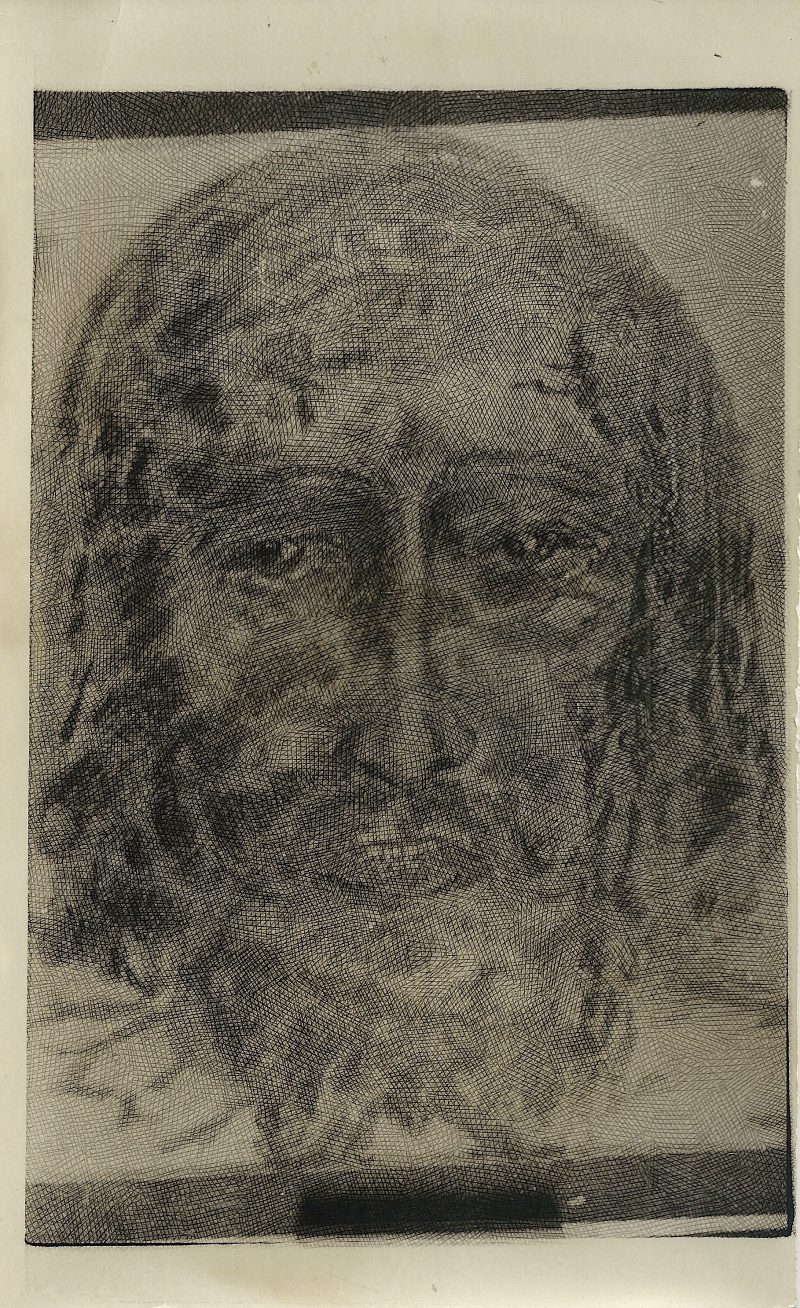

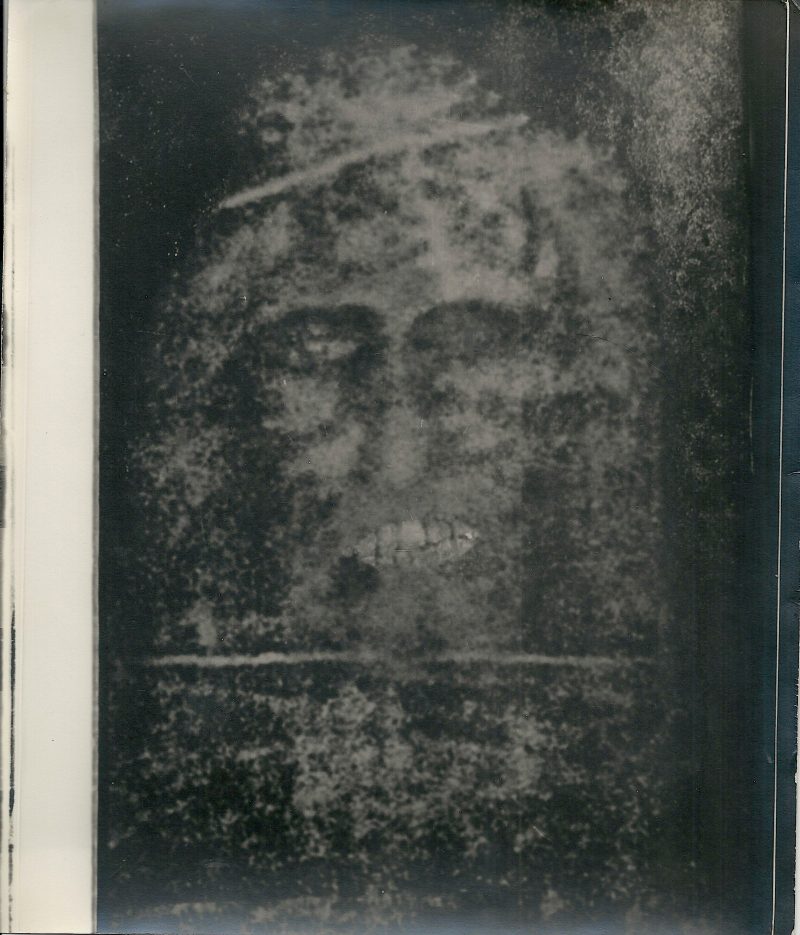

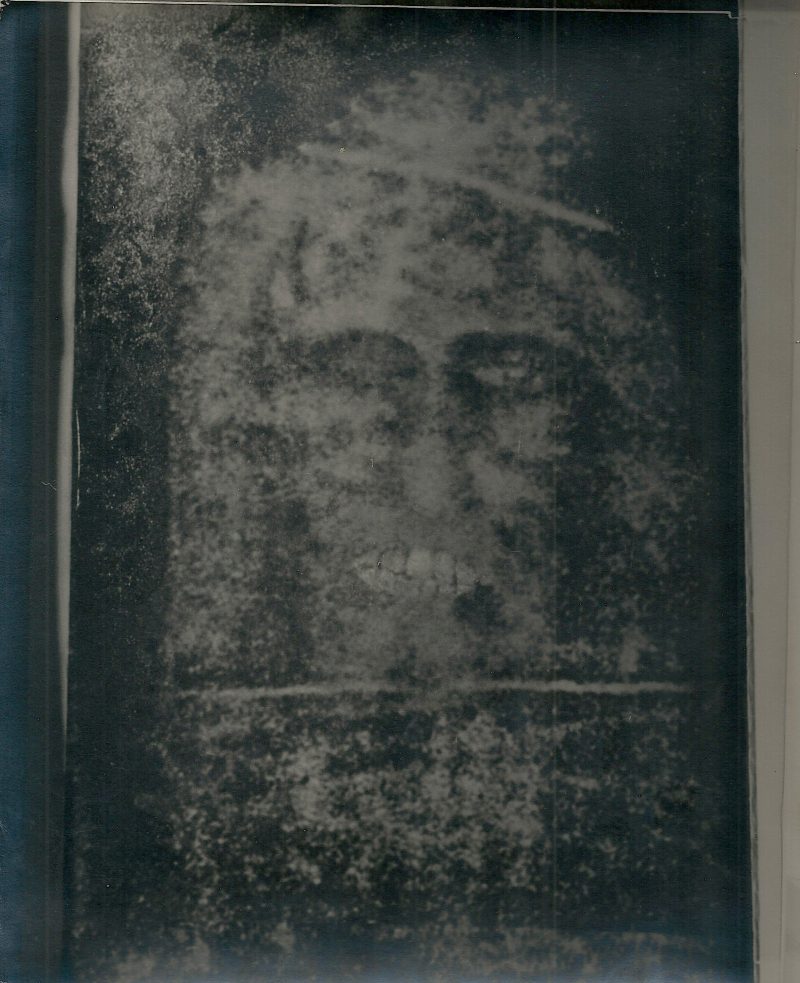

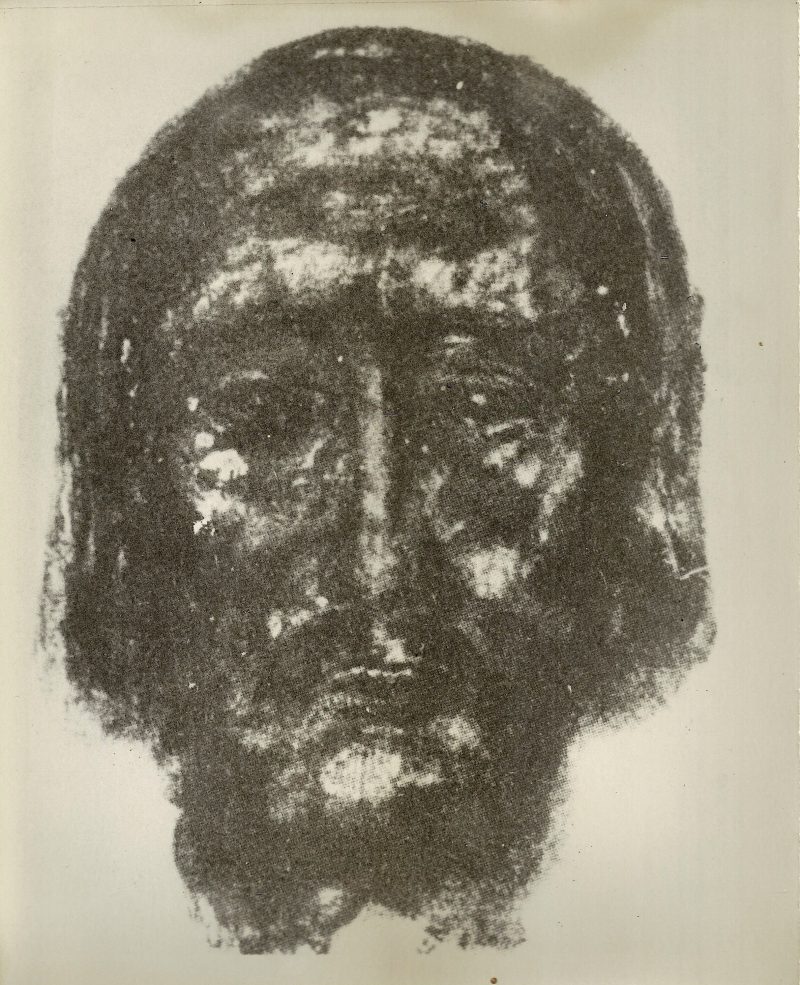

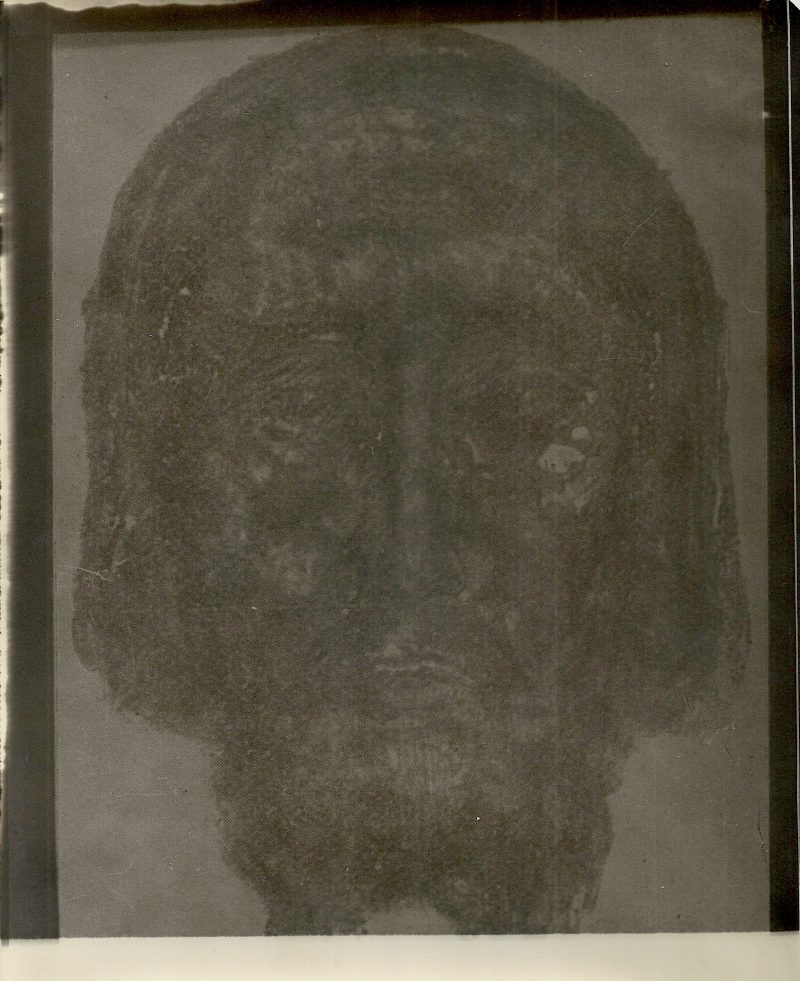

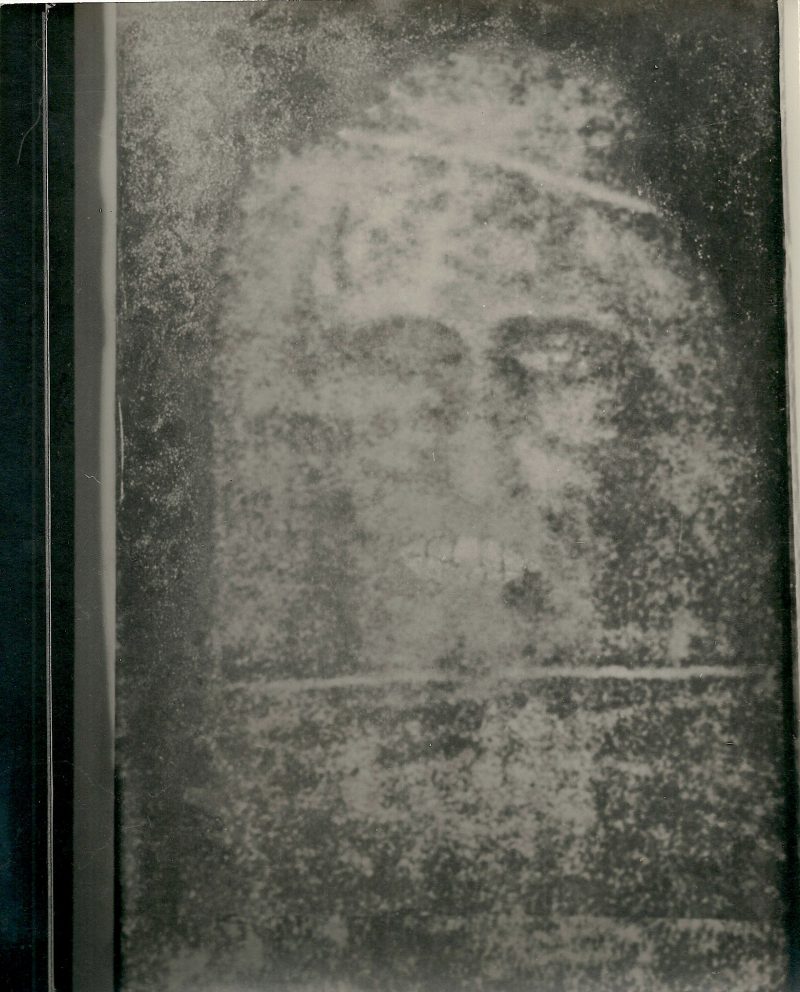

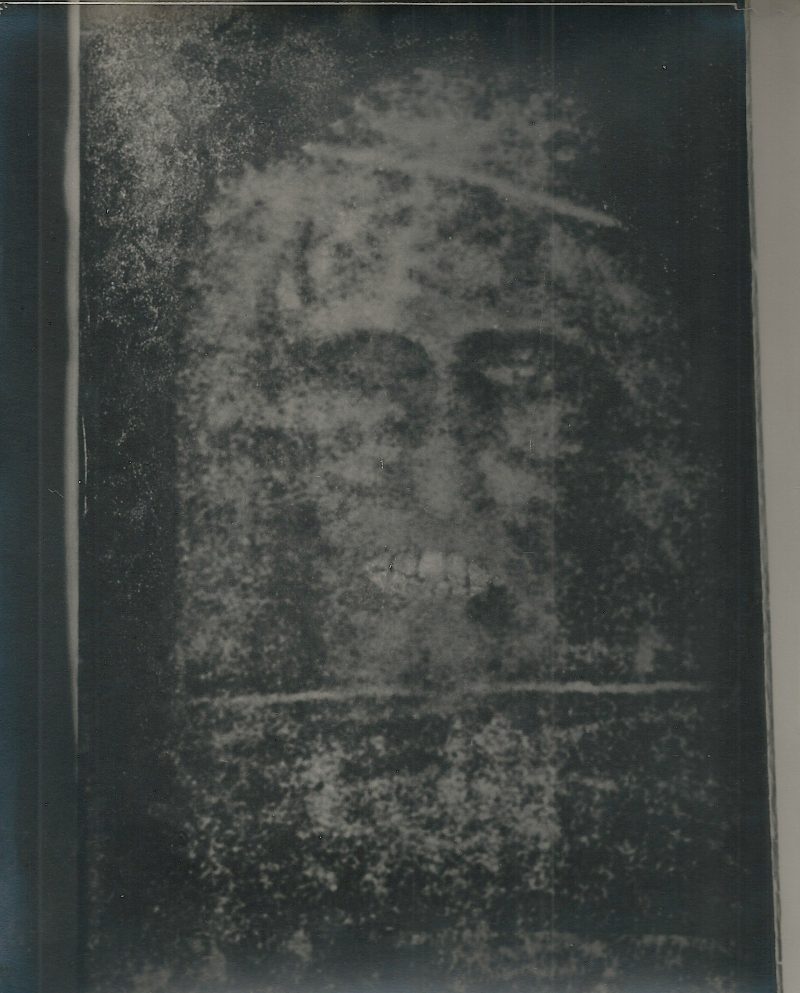

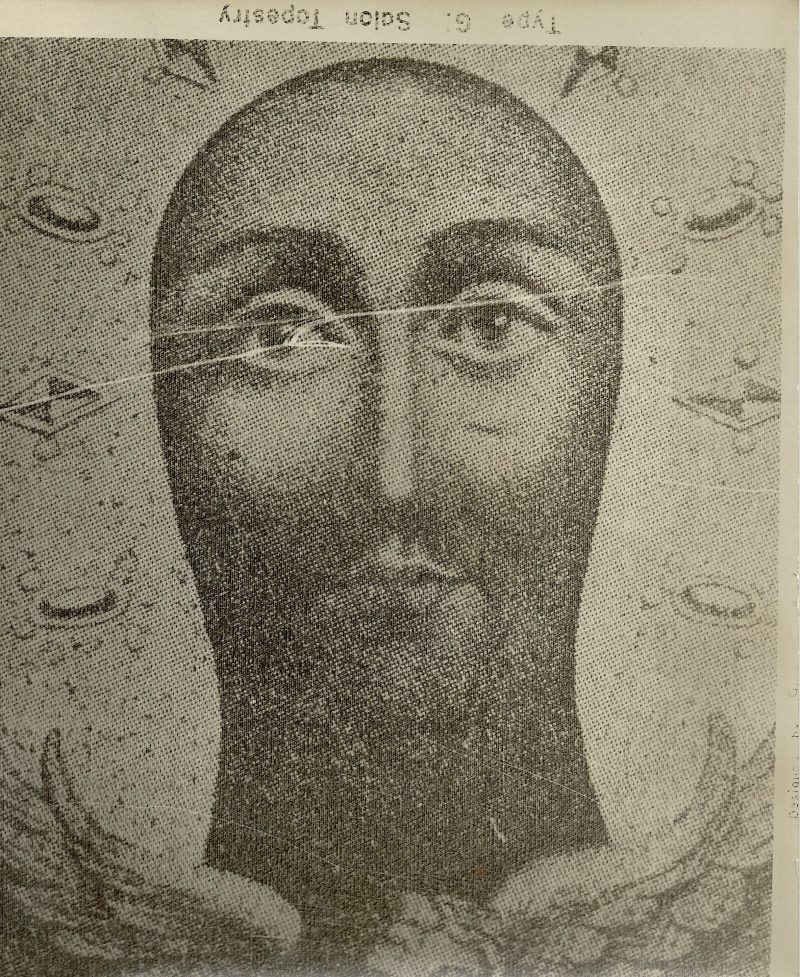

When the collection is seen as a whole, one next to each other, as depicted in the main image, it becomes a large artwork on it’s own; a very unique & spectacular montage depicting the face of ‘Christ after Death’.

Part of the Private Estate Art Collection of a Los Angeles Collector of Mid Century Art (1920-70’s), who passed away in 1999 in the USA. Acquired via his son in Puerto Vallarta, Mexico.

In several weeks of research, I’ve been able to conclude that the collection belonged to a great lover of the arts, with quite a variation in selection in his acquisitions. We can find paintings containing abstract, portraiture, still life & landscapes; along with quite a variation in photography from journalistic, picturesque to mildly erotic. The collection also include sculptures, coins & even Elvis Presley paraphernalia.

It is my understanding, going through most of the archives, that the collector had amassed an incredible quantity of art history books, magazines, newspaper clippings & hundreds of handwritten notes. I also conclude that the collector, along with his research, conducted art history talks at certain art institutions, I believe, as a self-taught art historian of sorts, which depicts his real passion; the sharing of his knowledge to others.

Is The Shroud Of Turin Really The Burial Garment Of Jesus Christ?

By Kaleena Fraga | Edited By Jaclyn Anglis

Published January 14, 2025

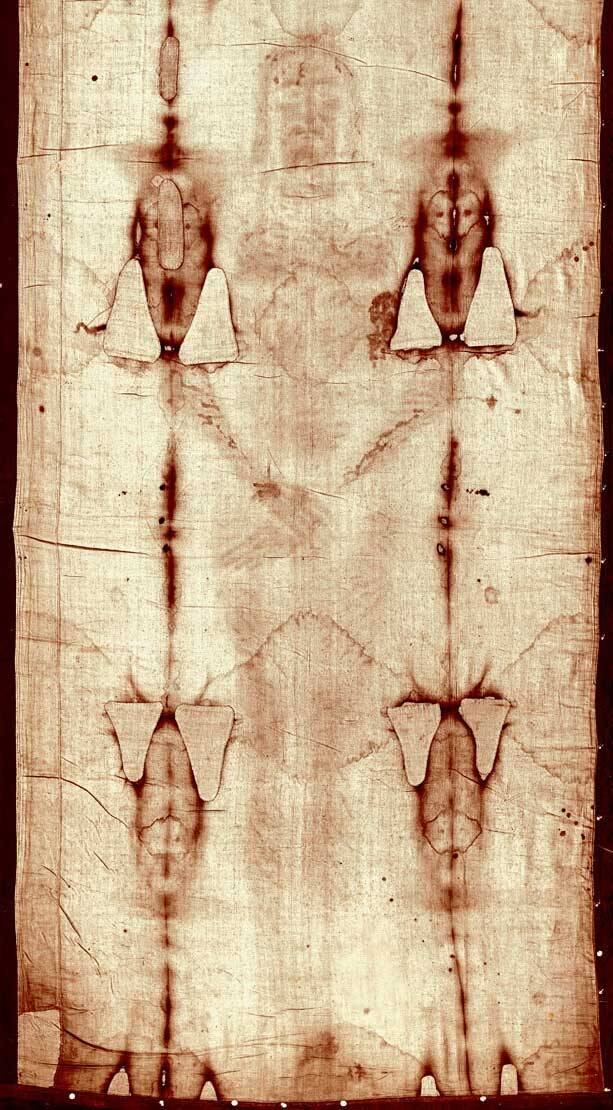

Stored in Turin, Italy since 1578, the Shroud of Turin seemingly bears the image of a crucified man — who some believe was Jesus of Nazareth.

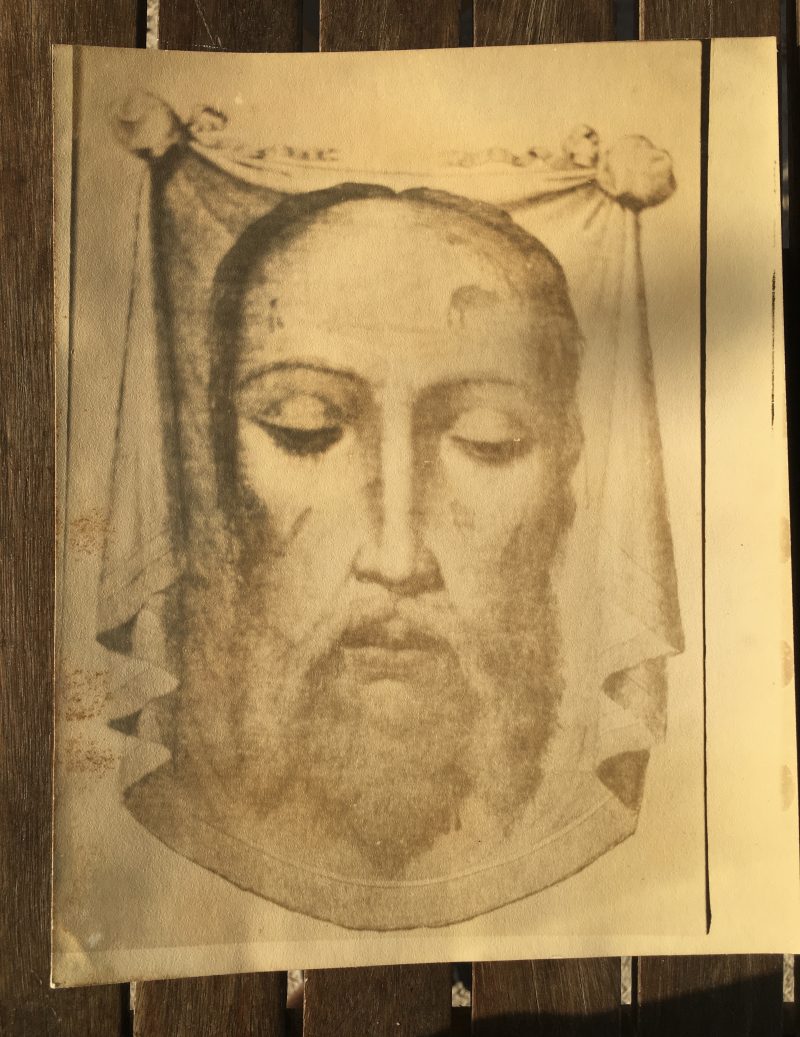

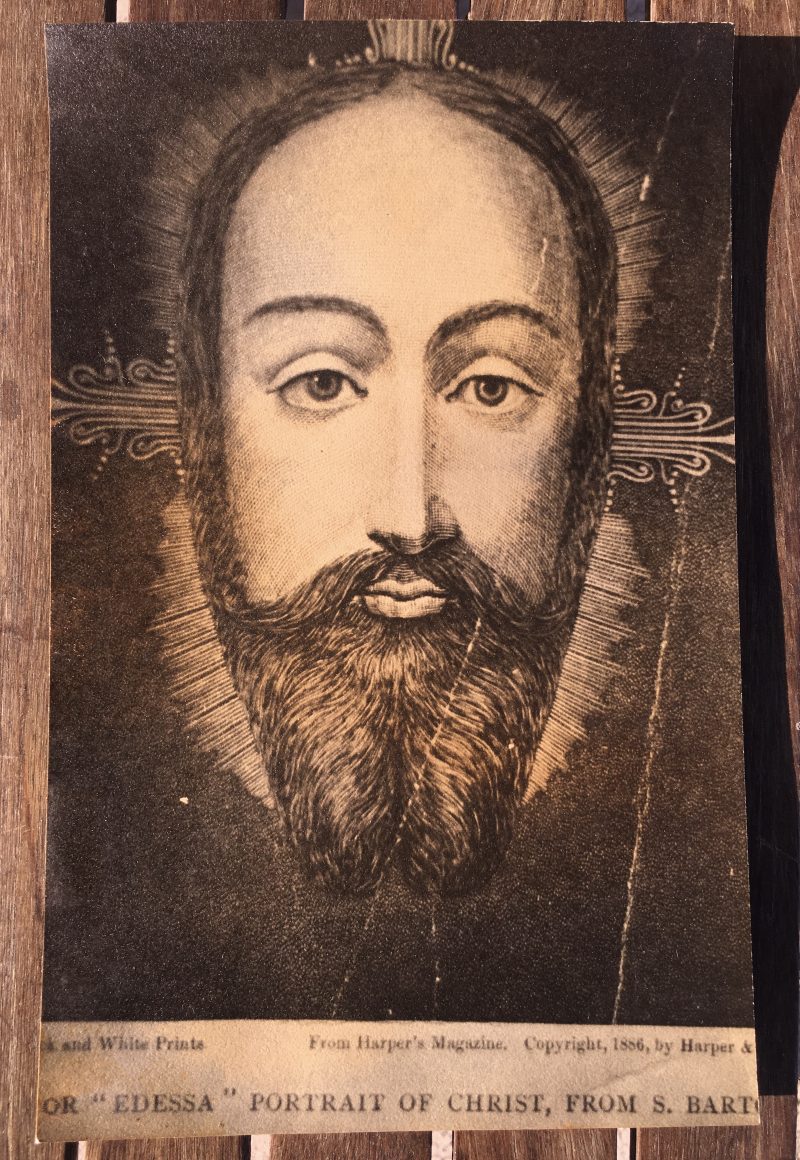

World History Archive/Alamy Stock PhotoSome believe the Shroud of Turin is the burial cloth of Jesus Christ, but its authenticity has been debated for centuries.

In the 1350s, a knight in Lirey, France came into possession of a peculiar object. There is no record where he found it, who he got it from, or where it originally came from. But it was, the knight claimed, an ancient burial shroud imprinted with the likeness of Jesus Christ. And the world has been debating the authenticity of the so-called Shroud of Turin ever since.

If it’s genuine, the Shroud of Turin is an astounding artifact. It seems to bear the imprint of a man who was crucified — and endured painful injuries from thorns on his head and wounds on his back from flogging.

So is the Shroud of Turin real? Studies performed on the object have turned up conflicting results. But the most recent investigation concluded, with some caveats, that the artifact could be about 2,000 years old.

The Murky Origins Of The Shroud Of Turin

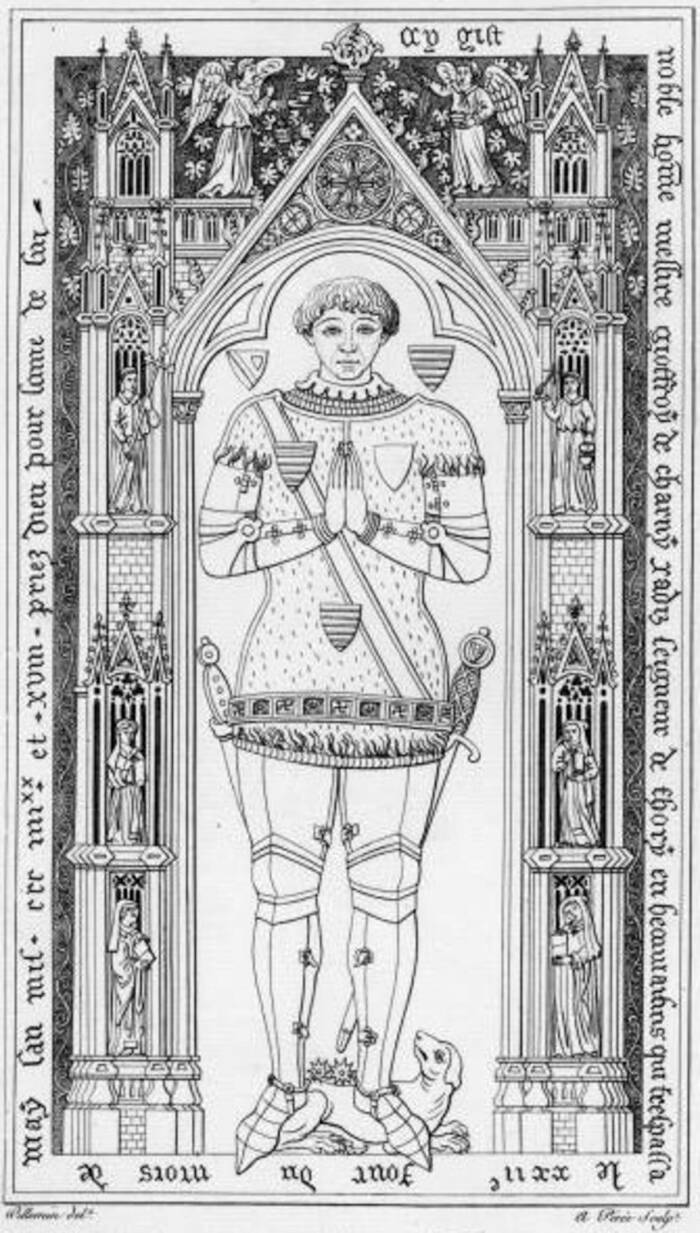

The History Collection/Alamy Stock PhotoFrench knight Geoffroi de Charny, seen here in his tomb brass, acquired the Shroud of Turin in the 14th century.

The Shroud of Turin first appears in the historical record during the 14th century. In 1355, it was put on public display in Lirey, France, after it was brought forward by a French knight named Geoffroi de Charny (sometimes also spelled Geoffroi de Charnay or Geoffrey de Charny) — who claimed that it was the burial shroud of Jesus Christ. Though the knight left no record about where he’d found the cloth, his military career had likely taken him to many places, including Smyrna, an ancient Greek city in present-day Türkiye. That said, de Charny died in 1356 before he could be thoroughly questioned.

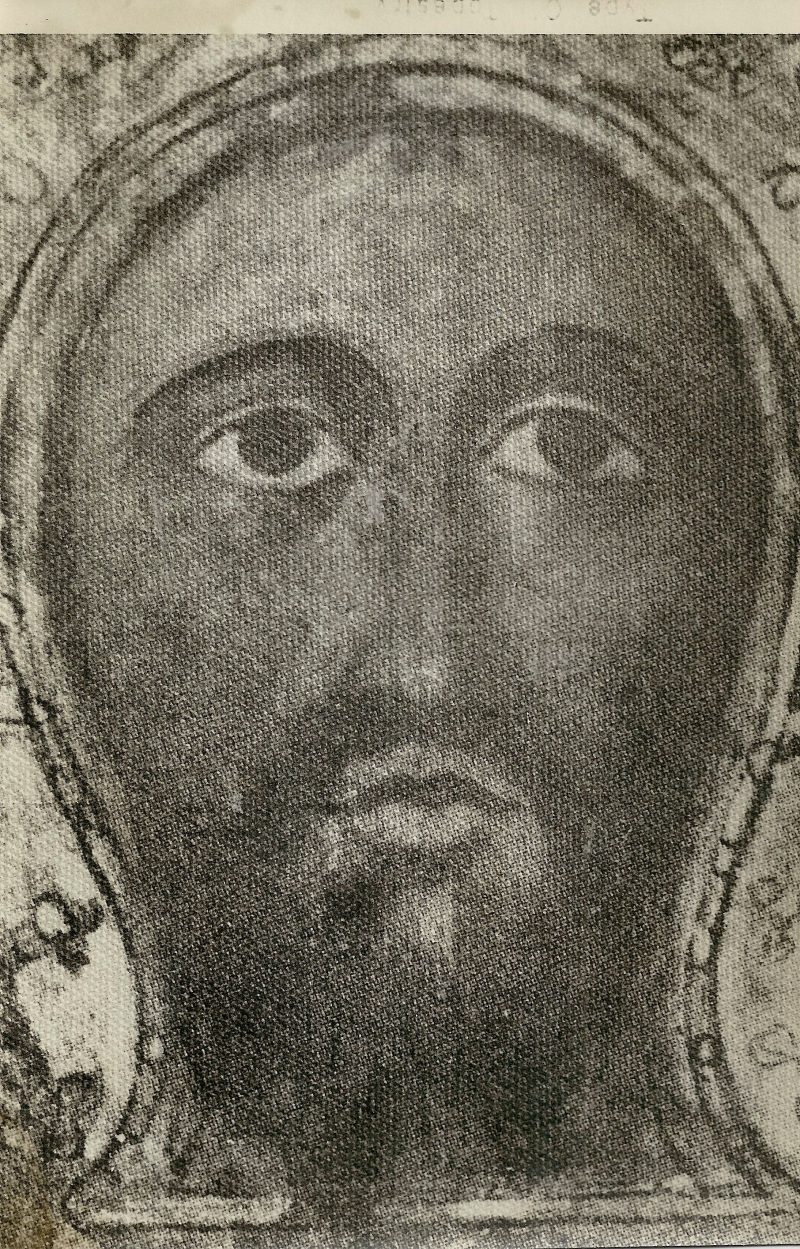

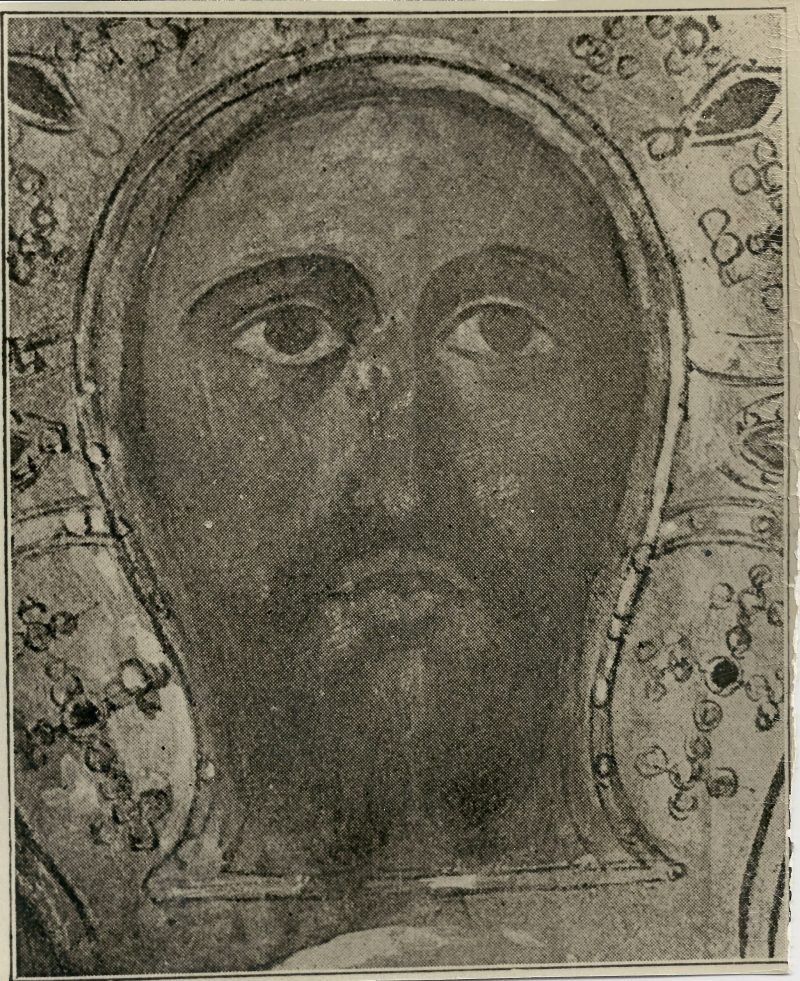

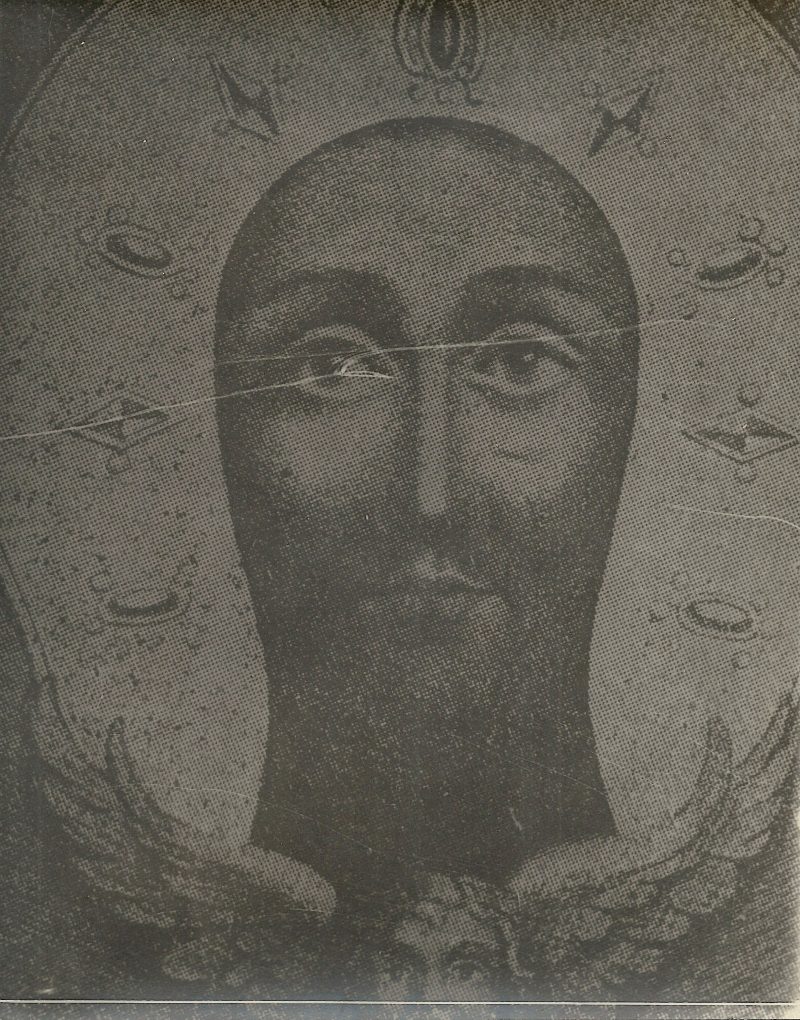

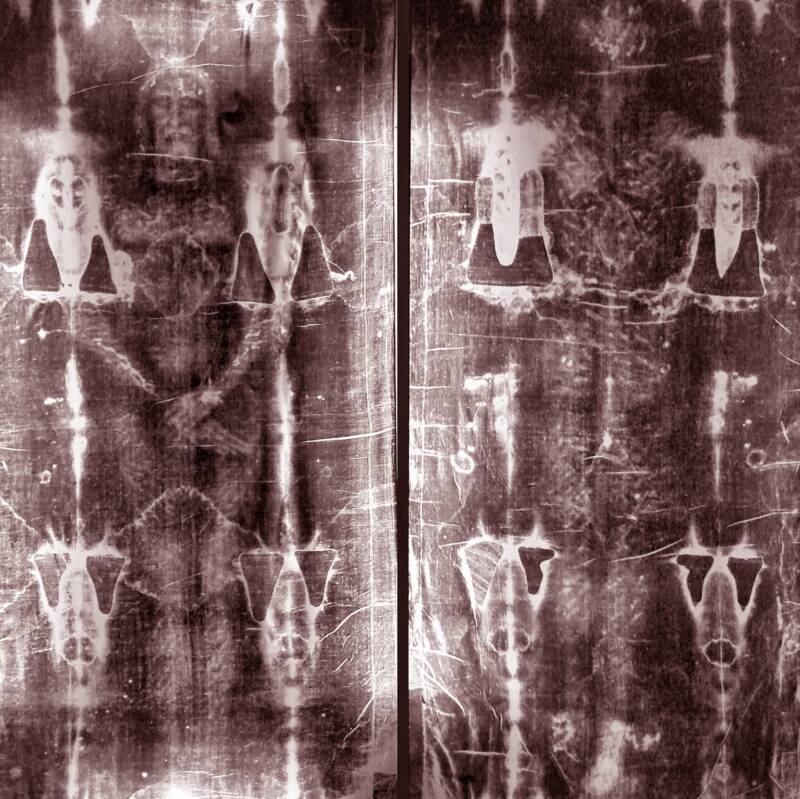

Though its origins were dubious, the Shroud of Turin looked tantalizingly authentic. Measuring about 14 feet, 3 inches long and 3 feet, 7 inches wide, the cloth seemed to show the faint imprint of a man who had been crucified. It looked as if the man had been laid down on the cloth, then wrapped in it, leaving an impression of his face and his injuries.

Public DomainA close look at the face imprinted on the Shroud of Turin.

It thus offered to answer questions about what Jesus Christ had looked likeand even Christ’s height (the figure in the shroud stood 5 feet, 7 inches tall). What’s more, it seemed to confirm the torture that Jesus Christ had suffered during his execution at Golgotha. The man in the shroud seemed to have injuries consistent with crucifixion, including wounds near his hands and on his feet (possibly from nails), marks on his head (possibly from a crown of thorns), and injuries on his back (possibly from being flogged). The shroud was also stained with a dark material that looked like blood.

But the object drew both awe and objections from the start.

As the Shroud of Turin drew pilgrims to Lirey, it also drew the critical eye of the Catholic Church. In 1389, the bishop of nearby Troyes wrote to Pope Clement VII to inform him that it was a fraud, claiming that it was “cunningly painted” and that the artist behind the stunt had confessed “the truth.”

Clement ruled that Lirey could continue to display the Shroud of Turin, but that they would have to specify that it was an “icon” and not a historical “relic.” That said, the debate over the Shroud of Turin’s status as an “icon” versus a historical “relic” would continue for several centuries.

Fire, Water, And Doubt: The Chaotic History Of The Religious Object

Public DomainThe Shroud of Turin was in the possession of the Savoy family for centuries.

The Shroud of Turin stayed in Lirey for decades. But in 1418, as fighting during the Hundred Years’ War moved precariously close to the town, Geoffroi de Charny’s granddaughter Margaret de Charny took the object into her possession to protect it. Though officials in Lirey tried to reclaim the shroud starting in the 1440s, Margaret decided to start exhibiting it elsewhere. In 1453, she sold it to the royal house of Savoy in exchange for two castles.

For this, Margaret was excommunicated. And the Shroud of Turin remained with the Savoys until 1986, when it was bequeathed to Pope John Paul II.

Over the centuries, the shroud faced various trials and tests, and church officials went back and forth about its authenticity. In 1503, a Savoy courtier claimed that the shroud was indisputably holy since it had been burned, boiled in oil, and even laundered, but “it was not possible to efface or remove the imprint and image.” In 1506, Pope Julius II seemed to agree when he declared that the shroud was not just an icon but an authentic relic.

In 1532, a fire broke out at Sainte-Chapelle in Chambéry, France, where the shroud was being held, badly damaging the garment. The object had been stored in a container that was adorned with silver, which melted onto the shroud and burned it. Burn marks — and water marks from extinguishing the fire — can still be seen on the shroud to this day.

Florian Pépellin/Wikimedia CommonsThe façade of Sainte-Chapelle in Chambéry, left, where the Shroud of Turin was kept in the early 16th century.

The object was later moved to Turin, Italy in 1578, where it has been ever since (and where it got its name: the Shroud of Turin). Today, those who wish to view it can see it at Turin’s Chapel of the Holy Shroud.

For a long time, the Catholic Church was largely silent on the shroud. And when popes did speak of it in the 20th century, they often had conflicting opinions about how to describe it. Pope Pius XII called it a “holy thing perhaps like nothing else” in 1936; in 1980, Pope John Paul II described it as a “relic,” which was “linked to the mystery of our redemption.”

But John Paul II also remarked in 1998 that the Shroud of Turin was “not a matter of faith.” The pope admitted that the Catholic Church “does not have the proper competence to pronounce on these matters” and thus “she entrusts scholars with the task of carrying out further research in order to find answers to questions relating to the Shroud…”

Indeed, scientists have long tried to determine the truth about the Shroud of Turin. But their investigations have also turned up mixed results.

Is The Shroud Of Turin Real? Here’s What The Science Says

Krzysztof Dobrzański/Wikimedia CommonsStarting in the 20th century, scientists tried to determine the truth about the Shroud of Turin — with mixed results.

For centuries, veneration of the Shroud of Turin was based on faith. But starting in the 20th century, scholars sought to unravel the shroud’s secrets with science. However, even though they’re now armed with new technology, they haven’t yet made a definitive call on the shroud’s authenticity.

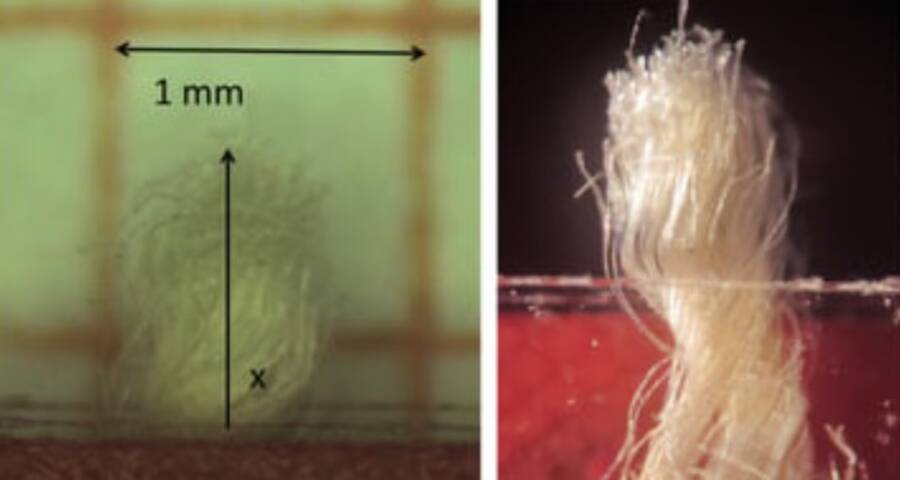

In the 1970s, one study suggested that the blood patterns on the cloth corresponded with someone who had died from crucifixion. A study in 2018, however, contradicted this by examining the position of the bloodstains. In the 1980s, another study used carbon dating to determine the age of the shroud, and found that the cloth dated back to between 1260 and 1390 C.E. — around the time when the object first appeared. This seemed to suggest the artifact was a medieval forgery. But a more recent study in 2022 found that the shroud could, in fact, date back to the first century C.E. If true, that would mean that the object came from the age of Christ.

This study argued that most of the shroud’s natural aging could have occurred before the 14th century. After that point, it was stored in cooler areas in Europe, which the scientists believe slowed its aging.

“The degree of natural aging of the cellulose that constitutes the linen of the investigated sample, obtained by X-ray analysis, showed that the [Turin Shroud] fabric is much older than the seven centuries proposed by the 1988 radiocarbon dating,” the experts argued in their study, published in Heritage.

Heritage/De Caro et al.A 2022 study argued that the Shroud of Turin could potentially be about 2,000 years old.

So is the Shroud of Turin real? Even if the 2022 study is accurate — and the study’s researchers stated that a “more systematic” analysis was needed — it only proves that the shroud came from the first century. It does not prove that it was used as a burial shroud for Jesus Christ specifically.

But the Catholic Church does seem to see it as an important object, even if more recent popes have avoided calling it a historical relic outright.

In 2013, Pope Francis called the Shroud of Turin an “icon of a man scourged and crucified.” He added that the centuries-old garment “invites us to contemplate Jesus of Nazareth… [and that] this disfigured face resembles all those faces of men and women marred by a life which does not respect their dignity, by war and violence which afflict the weakest.”

After reading about the Shroud of Turin, learn about when and where Jesus Christ was born. Then, go inside Jesus’ alleged tomb.

AUTHOR

A staff writer for All That’s Interesting, Kaleena Fraga has also had her work featured in The Washington Post and Gastro Obscura, and she published a book on the Seattle food scene for the Eat Like A Local series. She graduated from Oberlin College, where she earned a dual degree in American History and French.

EDITOR

Jaclyn is the senior managing editor at All That’s Interesting. She holds a Master’s degree in journalism from the City University of New York and a Bachelor’s degree in English writing and history (double major) from DePauw University. She is interested in American history, true crime, modern history, pop culture, and science.

MORE RESEARCH:

One of the more speculative tales surrounding the Shroud of Turin, which supposedly depicts the face of Jesus Christ, purports that the cloth was actually made by Leonardo da Vinci. The story goes that Leonardo passed off his own image as Christ’s, possibly as an act of hubris or to trick the Catholic Church. The theory has merits. According to traditional belief, Jesus imparted his image to his burial cloth when he was wrapped in it, but radiocarbon testing has dated the fabric to the Middle Ages. Yet dating the image’s genesis even to the 14th century is mystifying. The linen fiber is neither painted nor dyed—how was the image made?

We know that Leonardo, who made his masterpieces in the late 15th century, experimented with aged cloth. We know that he encoded his own face within the Mona Lisa and Salvator Mundi. We know he was fascinated by the anatomical effects of crucifixion. We also know that the optical science underlying photography was more or less understood in Renaissance Europe and during the Arabic Golden Age—Ibn al-Haytham’s Book of Optics had been translated into Latin by the early 13th century—and that alchemists knew its basic chemistry. And really, who other than Leonardo would have been as capable of creating such an enigmatic and technically inexplicable image?

Most art historians and critics attribute the first fixed photograph either to Nicéphore Niépce or Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, but in his book Photography and Belief, David Levi Strauss writes that if you believe the mysterious face on the cloth is really the work of Leonardo, then the Shroud of Turin is actually the world’s oldest photographic image. Interestingly, Strauss doesn’t say whether he believes the theory, but then his book isn’t a revisionist history of photography. Strauss’s unorthodox understanding of photographs has informed incisive essays on topics from Joseph Bueys’s precognition of 9/11 to torture scenes at Abu Ghraib to the feminist-Marxist Kurdish revolution in Rojava. In Photography and Belief, he sets out to develop a coherent philosophy of why we believe in photographs. Strauss proposes the Leonardo theory as a reason: “Shroud literature is every bit as conspiratorially arcane as JFK-assassination literature, which is also centered on photographic evidence,” he writes. “But both of these groups of literature—the sacred and the secular (religious faith and political power)—reveal much about the nature of image and belief.”

Photography, Strauss argues, may be a relatively new form of technology, but photographs are an ancient form of images. His theory hinges on the fact that photographs overlap with objects the Byzantines called acheiropoieta, medieval Greek for “icons made without hands.” If Leonardo did in fact impart his image onto ancient cloth and substitute his likeness for Christ’s, his proto-photograph would have been considered in Renaissance Italy a “totally magical act.” It would have involved an instance of belief. When photography was officially “invented” in the 19th century, this preexisting system of belief was transferred onto it. Photographs may be a technical form of image-making, but Strauss proposes that our thinking about them is akin to the mental process by which cultures believe in magic. By the time daguerreotypes were introduced in 1839, he writes, “belief in photography had already been around for millennia.”

It’s worth stopping to ask why, in 2021, we need another theory of photography, particularly one that finds its answers in the Middle Ages. For decades, one of the recurring debates in photographic criticism has been whether photographs participate in the “aestheticization of suffering.” Do images of suffering beautify tragedy, making us immune to, or worse, oddly attracted to it, or do they actually increase our empathetic connection? Do photojournalists expose injustice or do they pawn misfortune for money, clout, and adrenaline?

Strauss recounts the debate’s broad strokes through writings by Walter Benjamin, John Berger, Roland Barthes, Susan Sontag, Julia Kristeva, and others. Perhaps the most significant shift occurred when Sontag, who had previously argued that images of violence were “desensitizing,” revised her views in 2004. “To speak of reality becoming a spectacle is a breathtaking provincialism,” she wrote in Regarding the Pain of Others. “It universalizes the viewing habits of a small, educated population living in the rich part of the world, where news has been converted into entertainment.… It assumes that everyone is a spectator. It suggests, perversely, unseriously, that there is no real suffering in the world.”

Still, critics and photographers disagree today about whether we feel real empathy when looking at terrible images or if they make us apathetic toward misery. Strauss’s argument offers a way around these debates by stressing the question of belief. Individual images simply have less power than the systems that generate them, he maintains, and these systems have adapted themselves to take advantage of our inclination to put our trust in photographs. Strauss has long argued that the answer to our crisis of belief in images is, surprisingly, more images. The experience of 9/11 jolted his belief. The architects of the attacks, Strauss wrote in 2003, “tried to turn our extreme attraction to images of violence and catastrophe against us, but they underestimated the extent to which these images have actually supplanted reality for us.” The attacks, which were meant to be proliferated through images, are the most photographed event in history. A decade after they occurred, when Wired interviewed Strauss about the Obama administration’s decision to withhold photographs of torture at Abu Ghraib, he said, “I want more images. In that way, I guess you could say I have gotten what I want, since today’s communications environment makes more and more images available to us all the time.”

Strauss doesn’t see us retreating from an imagistic society, and because he loves images (he’s an art critic, after all), he wouldn’t want us to try. Still, he’s cautious about the power photographs have over us, and their ability to bond us to their world, so he argues it’s time to increase our general literacy in images. When Strauss says he wants more images, he means that he wants more kinds of images. He wants artists and photographers to open new pathways and expand our symbolic order, in part because our belief in photographs leaves us vulnerable to abuse, from political propaganda to corporate advertising. After a literacy of images, Strauss wants a literature of images.

Before we can get there, though, we have to go back to the origins of our belief.

A variant of the phrase “seeing is believing” first appeared in 1609, but already it was phrased as a proverb, as received wisdom. Its inspiration was probably the biblical story of doubting Thomas, the Apostle who refused to believe in Christ’s resurrection until he saw the wounds for himself. Strauss writes that the parable “asserts that believing should not be dependent on sight—that believing based on sight is an inferior belief.” When S. Harward wrote, in the 17th century, that “Seeing is leeving” (which means loving and comes from the Anglo-Saxon lief), he inverted Jesus’ counsel and stood behind Thomas’s skeptical belief.

The history that allowed for this inversion is a long one. In the fourth century, the word “image” referred to Christ as the image of God. But Neoplatonist theologians had to reconcile Christian creed with Plato, who argued that images are inferior to original forms—and the church couldn’t devalue a third of its Holy Trinity. A solution came from Saint Augustine, who believed that God’s image resided in the human mind rather than Jesus’ mortal body. The reconciliation of these two antipodal convictions permitted belief in acheiropoieta: seemingly miraculous images, whether manifested from nothing or purely imaginary, became proof of the divine presence of a Christian God. Images were understood to be emanations rather than representations. The idea took hold and is more or less how the Catholic Church reconciled devotional icons with the Ten Commandments’ prohibition of idolatry. Comparatively, Islam quickly distinguished between images in general and images of God, and consequently it continues to proscribe depictions of Allah and Muhammad, which is similar to taboos in the Jewish faith. But the root of this belief explains centuries of varied iconoclasts, from the Protestant Reformation to ISIS: Destroy the image of one’s deity, its emanations, and you destroy one’s ability to believe. Acheiropoieta were the preferred targets for Byzantine iconoclasts.

Strauss spends the last half of his book triangulating three contemporary sources who bolster his theory: Vilém Flusser, a Czech-born philosopher of media who fled the Nazis for Brazil in 1939; Ioan Couliano, a scholar of Renaissance magic who was likely assassinated by Romanian secret police in 1991 after a lecture at the University of Chicago; and Hans Belting, a German art historian known for his studies in Bildwissenschaft, or image-science. The three are united by their understanding of belief as a science of the imaginary.

Strauss draws from Flusser his conviction that the invention of photography was as influential as the invention of writing because both had the potential to fundamentally change the way we think. In Eros and Magic in the Renaissance, Couliano wrote that the Protestant Reformation was not actually the beginning of modern scientific thought but rather an assault on the imagination; using Giordano Bruno’s writing, he argued that Protestants destroyed Catholic icons because they feared worshipers were being bonded inappropriately to earthly images. Belting pushed this forward, arguing in Likeness and Presence that the entire idea of “art” was conceived basically via a dislocation of religious belief among a small entrepreneurial cadre of introspective painters who suddenly found themselves without the Catholic Church for a patron.

The invention of photography provided a useful cover story for this kind of magical thinking. “Seeing is believing” became the mantra of a new medium that claimed its roots in the scientific method. Some, like Benjamin, troubled the premise, noting that photography was associated with devilry from the start. “The human is created in the image of God and God’s image cannot be captured by any man-made machine,” he wrote in 1931. “This is how the philistine notion of ‘art’ enters the stage.” And just like that, a slippage occurred. Photography inherited the magical system of belief that surrounded icons and acheiropoieta. A camera, so it’s said, can only record the reality in front of it, and with this claim toward objectivity, a photograph came to equate total belief in the world a photograph depicts.

Since photography’s earliest days, innumerable writers and photographers have demonstrated that photographs can lie as easily as words. If you place the invention of photography in the 19th century, then one of the very first photographs, Hippolyte Bayard’s 1840 Self Portrait as a Drowned Man, was a lie and a hoax. Knowing this, why would anyone believe what they see?

Strauss revisits this history to show that the long-running debate around photography’s verisimilitude sidesteps a more pertinent point. Under cover of the debates on whether we should believe what photographs show, a kind of “optical consciousness,” to borrow a phrase from Benjamin, has settled in—and we aren’t going to return to an earlier mode of thinking. Strauss wants us to see that we don’t choose to believe in photographs. Rather, we believe in images when they “emanate” or come out of a world that we already believe in. “Belief does not arise from the object of the photograph,” he concludes. “It comes from the subject, from us.” In the end we’ve reached a second proverbial inversion: If belief comes before seeing, then the phrase could be rewritten, “Believing is seeing.”

The consequences of this reversal can’t be overstated. Last year, Strauss published a book titled Co-Illusion: Dispatches From the End of Communication, in which he argues that Donald Trump’s 2016 victory came, in part, from his ability to weaponize images in mass media. Strauss calls this new age of electioneering “iconopolitics” and illustrates that it’s predicated entirely on which side can get more people to believe in its images. The right has proven particularly savvy at this game, as they’ve tapped into an exceptionally conspiratorial subset of the US population and fed them dangerous but compelling images. The GOP traffics in conspiracies—be it voter fraud or promoting QAnon—not necessarily because it believes them but because, for its supporters, they constitute an aesthetic and an identity.

Technical images do the most damage on social media, where they circulate widely, quickly, and without sufficient context. When, in 2014, Strauss said that he wanted access to more images, he probably didn’t envision his wish coming true to this degree. If photographs and technical images are now our primary means of processing information, how does that alter the social contract of a community or even a nation? If we don’t even understand how and why we believe in photographs, how can we fully comprehend the consequences of deepfakes and social media echo chambers?

There’s a way to interpret Photography and Belief as a call to slow images down. Even as we produce more and more images every day—and our methods of communication increasingly rely on them—Strauss’s book, like all good criticism, attempts to carve out space for freedom. His method allows us to look carefully and consider the impact of the status changes on society—an ever more important task given the breakneck pace of today’s media. “Belief in images has become the test case for the social,” he writes. “If we are to believe in the world, we must have images of it.” That includes images of the world as it truly is, but also images of the world as we would like it to be. Or else, if there’s nothing to see here, there’s nothing to believe.

Source:https://www.thenation.com/article/culture/photography-belief-david-strauss-review/