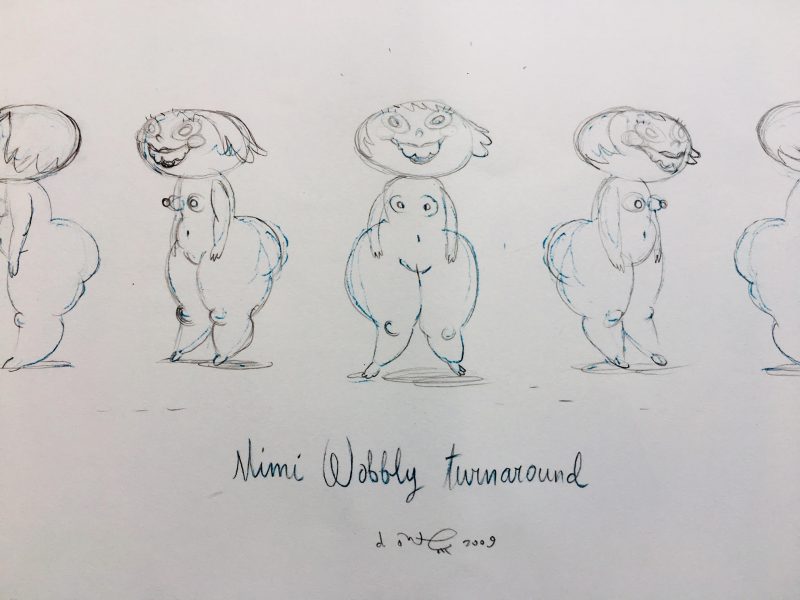

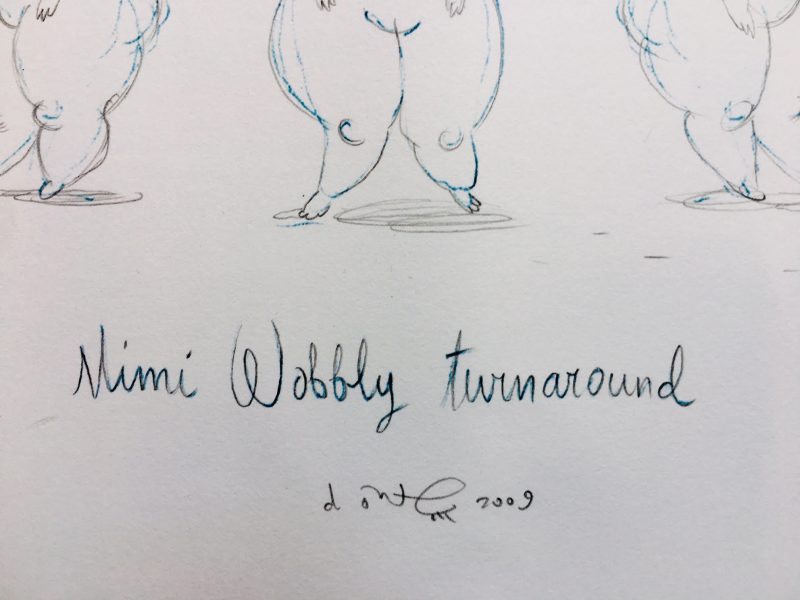

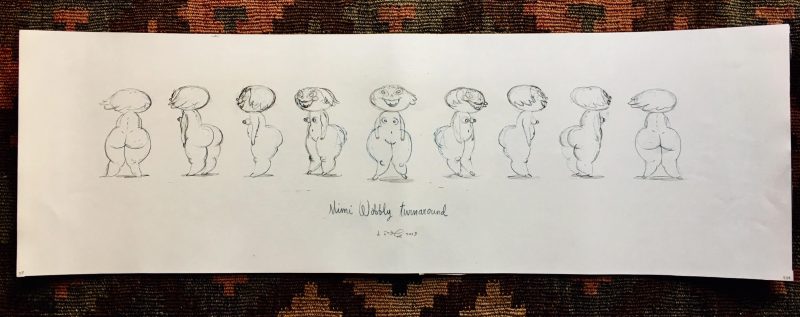

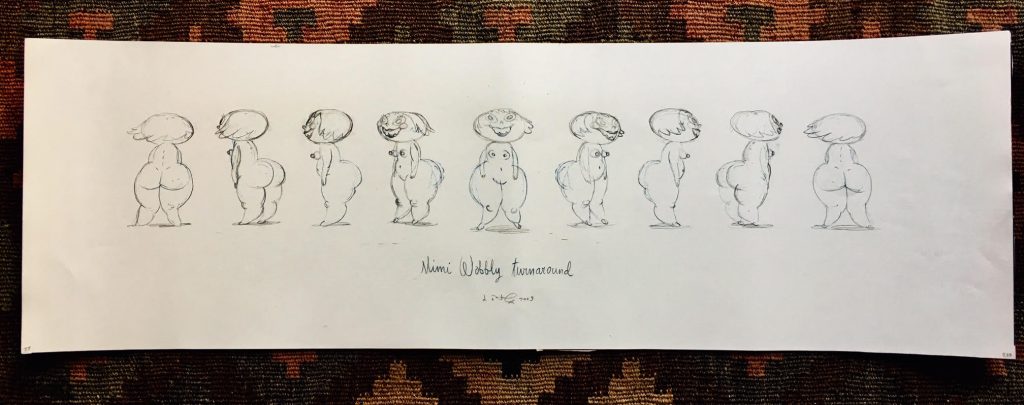

Dave Cooper Drawing 2009

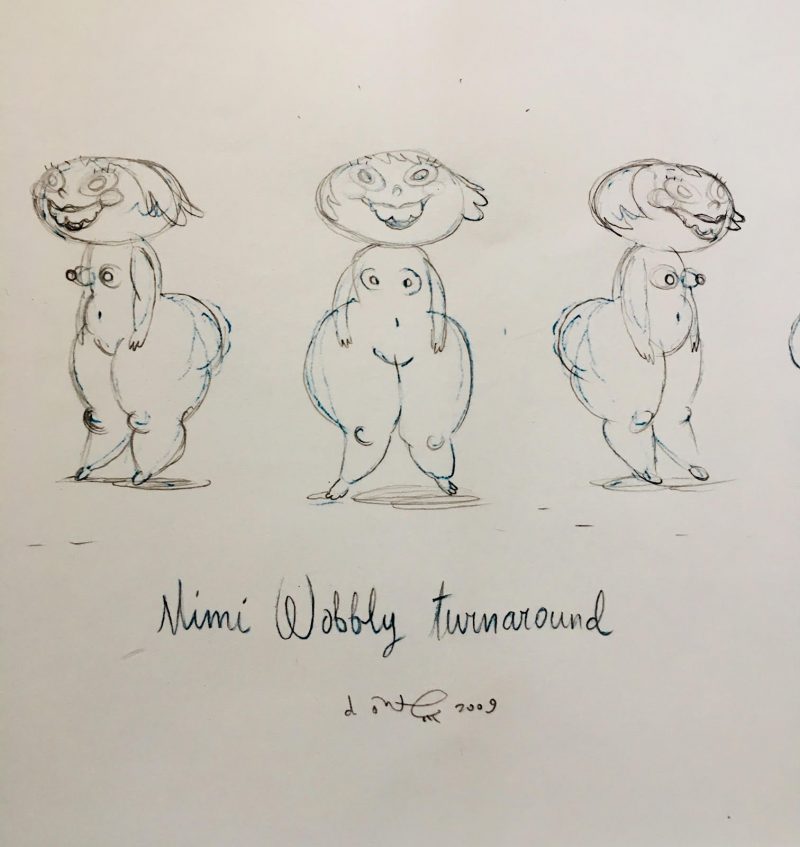

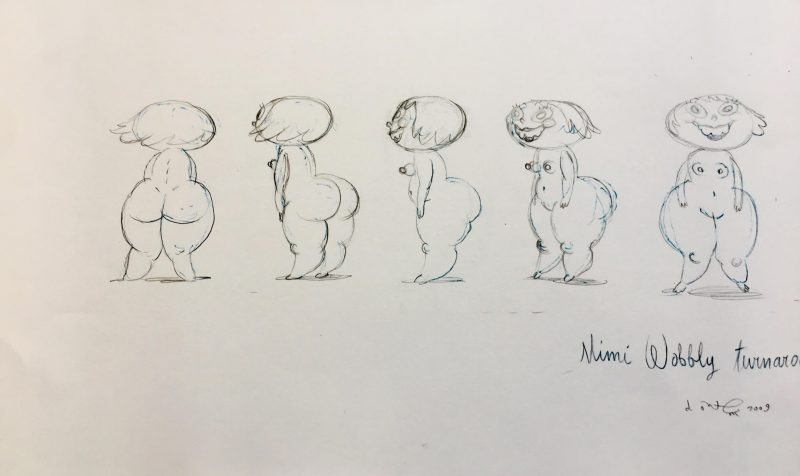

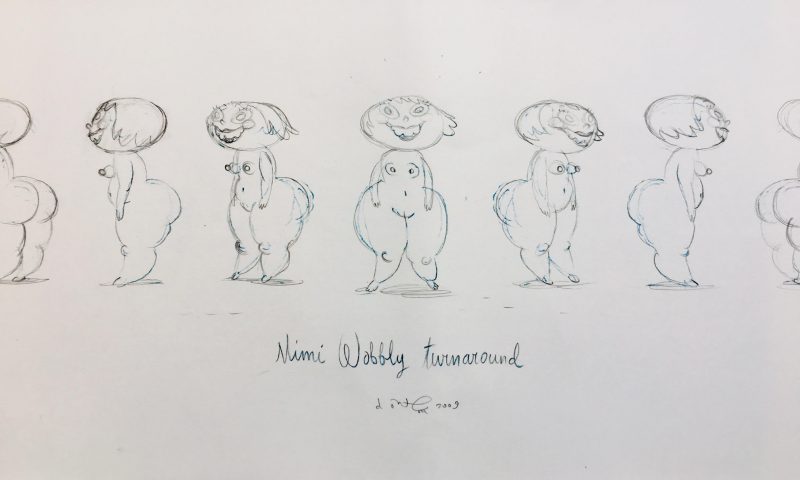

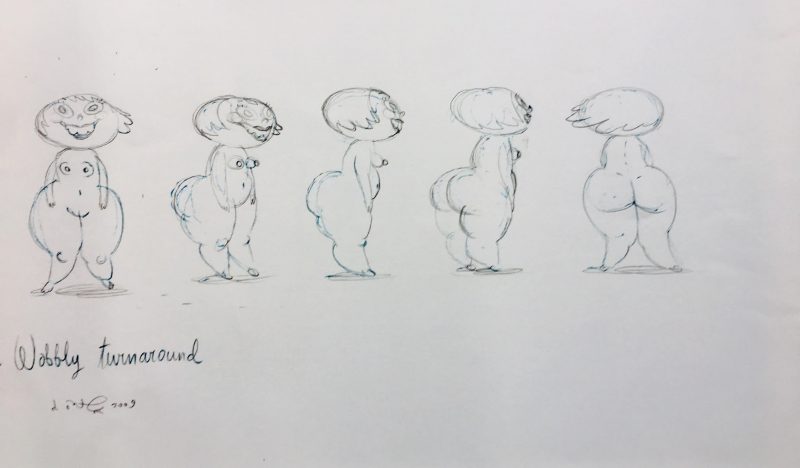

Authentic Pencil Drawing by Ottawa artist Dave Cooper. Measures 23 inches width x 7.5 inches height. Study drawing on white paper stock, for the character he created entitled “Mimi Wobbly Turnaround”. Signed on front & dated 2009. (lower bottom). Was exhibited at La Petite Mort Gallery in the same year. Purchased by the owner of the gallery.

Estimated at $800.

Compare listed prices at Montreal gallery: https://yveslaroche.com/en/artist/dave-cooper/

BIOGRAPHY

Dave Cooper, born in Eastern Canada, is a cartoonist, commercial illustrator and a graphic designer who currently lives in Ottawa, Canada. At the age of 18 he began his professional career, making what were then called “alternative comics”. Gradually Cooper made a name for himself and honed his craft. In about 10 years, his comics had gained a solid cult following, and praise from such luminaries as Robert Crumb, Art Spiegelman, and film director David Cronenberg. In fact, Cronenberg penned an introduction to Dave’s last substantial work, the graphic novel Ripple. In recent years Dave has won a slew of awards, been translated into French and Spanish, and has exhibited his comic book artwork all over North America and Europe.

dave cooper began his career in the 90s, making underground comics for Seattle’s Fantagraphics Books. his graphic novel Ripple sported an introduction by David Cronenberg. At the turn of the century, dave morphed into an oil painter, showing alternately at galleries in Los Angeles and New York City. Monographs of his paintings had introductions by David Cross, and Guillermo del Toro (Dave’s biggest patron). Around 2008 Dave turned his attention to the field of animation, ultimately getting two of his kids television shows greenlit- PIG GOAT BANANA CRICKET (co-created by Johnny Ryan) for Nickelodeon, and THE BAGEL AND BECKY SHOW (based on his kids book, BAGEL’S LUCKY HAT for Teletoon. PIG GOAThas been on the air in the U.S. since the summer or 2015, and THE BAGEL AND BECKY SHOW will air in the winter of 2016. in the spring of 2017 will return to print and oil painting with an ambitious slate of bizarre publications, and bodies of oil paintings. Dave lives in Ottawa Canada.

INTERVIEW: Page45.com Review by Stephen

“This is making me feel queasy!” Alternatively: “Oh my god that’s upsetting.”

How we have missed Dave Cooper in comics! There are few in this medium who can make us all squirm in quite such a spectacular, deep-seated fashion. Not for Dave Cooper, the momentary, transgressive gag: this is far more profoundly unsettling, with the visual craft (and specific, lino-cut textures in places) of Jim Woodring.

Cooper knows his nightmares so well. Come to think of it, he knows mine pretty intimately too. Not the specifics, but the patterns and underlying tone: hopelessness, embarrassment, anxiety; attempts to fix things which only exacerbate the situation; frustration, fear and failure. Guilt.

There are the swift, dream-logic transitions through invisible, intangible doors which will not reopen, so you stray ever further from your intended destination or the path you supposed might keep you on course. Often, there is a clock ticking silently away. Having lost someone or been left behind, you strive to catch up and though you may glimpse them again, fleetingly, perhaps in the distance or in conversation with others, meaningful contact is rarely possible. Elements become icky: I know of at least two other friends who dream of toilets so unbelievably foul that no human being should encounter them.

(I once did, BTW, in a hotel in St. Germaine, Paris, whose inner courtyard had so long lost its glass roof that the wooden stairs leading up to the bedrooms had rotted with rain, taking a couple of the steps clean away and making those that were left feel precarious at best, soggy. The room doors didn’t lock, but the single toilet, the size of a communal shower, was its pièce de résistance, its hole inaccessible by a good few feet, surrounded as it was with – anyway.)

There are no latrines here: I’m trying to describe the underlying elements of Cooper’s narrative without delivering its details. The two tales aren’t presented as dreamscapes, either – or at least not ‘Bug Bite’ – and that makes what transpires even more unsettling.

In ‘Bug Bite’ glossy-eyed, lower-lip-biting Eddy Table flies to a big city – possibly the Big Apple – with his family: rosy-cheeked wife with her quaint, retro rolled-up hair-do, more contemporary, long-haired and baggy-clothed son Zak, and daughter Nico with platted pigtails. Proudly, they are on parade. Mama:

“It’s so nice to be travelling together as a family.”

It’s already a strange environment: an industrialised version of those ancient cities in Jordan et al, hewn into rock faces with dark, gaping, glass-less windows, but fashioned in concrete instead. The traffic is mid-20th Century and anthropomorphic. The resolution of the backgrounds is blurred throughout, as if they’re moving through an aquarium or at least not at one with their environment, and the colours are all khaki and matte, while the family’s wide eyes glisten and gleam.

“Everything’s the same, but different!”

“Yeah, like a reflection in a funhouse mirror.”

On cue, buxom Dave Cooper ladies stride and strut through the streets with fulsome thighs and lots of extra wobbly flesh. Already the ideal of the united, unflustered family outing begins to melt away as Eddie’s eyes become engorged, popping then flopping out of his skull to loll about on the pavement like… you know. And it hurts. We as readers wince: with vicarious embarrassment and anxiety, but also the visceral, physical discomfort we can all recall of having grit in our eyes.

Son Zak attempts to lend a helping hand, to push his dad’s eyes back into their sockets and in so doing becomes innocently complicit, and that’s exactly when a former lady acquaintance called Mimi happens by, while wife and daughter stride on, unsuspectingly.

We have only just begun, but the pattern will be replicated in increasingly anxious and distorted ripples and reflections. I’ve already deployed all the words necessary to describe the most extraordinary, arresting two final panels. So I won’t be using them again.

The graphic novel’s flipside is ‘Mud River’ and the clock’s ticking faster than the first from get-go as a solitary Eddie hot-foots his way through a more overtly hostile countryside environment towards his only means of escape from the titular, impending threat: his parked car. Did I mention that the vehicles here had been imbued with certain human aspects? His car refuses him entry, its doors steadfastly shut. So Eddie gains access another way.

The familiar and the pliable become other and alien. Its scale askew, the car’s controls lie tantalisingly out of reach and its functions are frustratingly altered. It no longer serves its customarily complied-with purpose, so Eddie hitches a very different ride from the mud-slide. I loved its ornamental prow.

The two tales are separated by twin tableaux apposite to each, populated by multiple Eddies and others roaming free from both anxiety and guilt, with glee. He certainly takes full command of the joysticks. I’m trying to be discreet.

There’s a secondary interstitial layer too, but I’ll leave that to you.