Deadly Prey Gallery

“Spirit of the Beehive”

Upcoming Exhibition September 2020 in Ottawa, Canada.

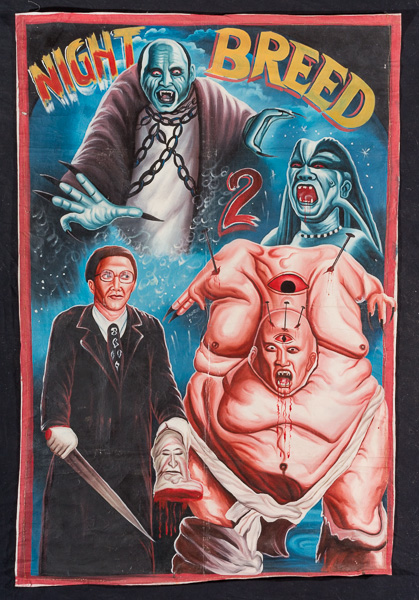

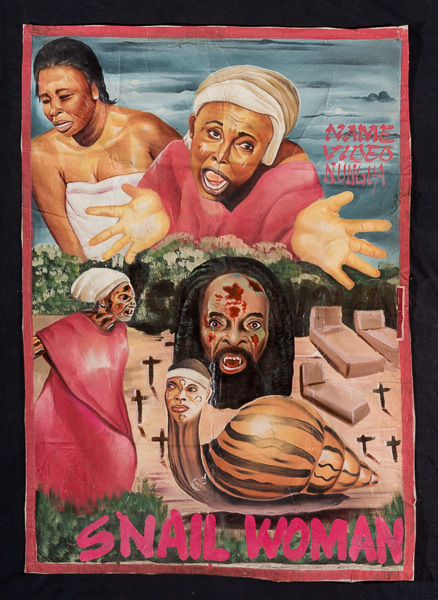

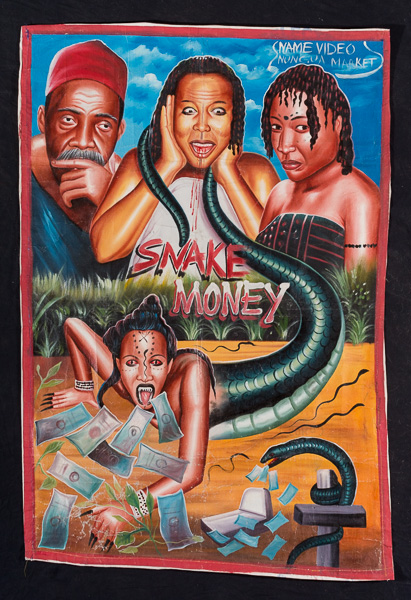

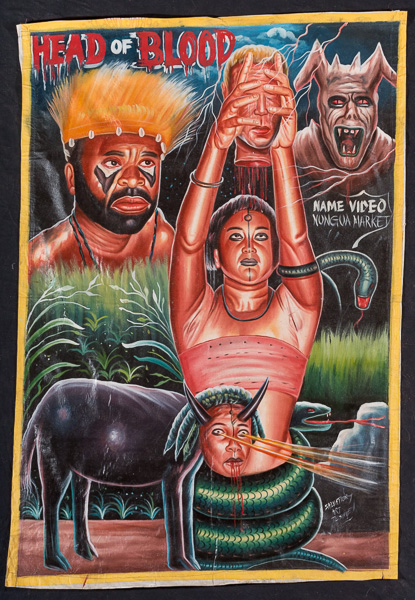

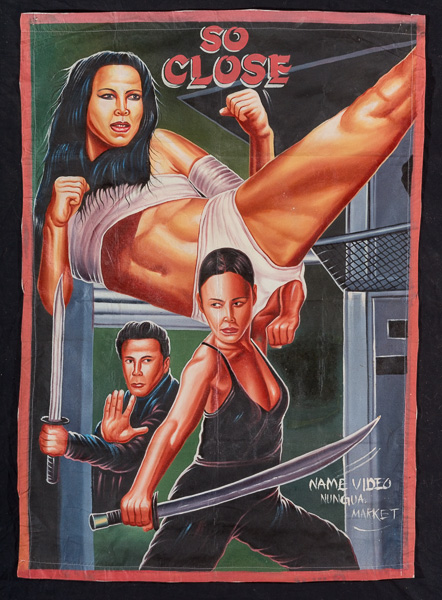

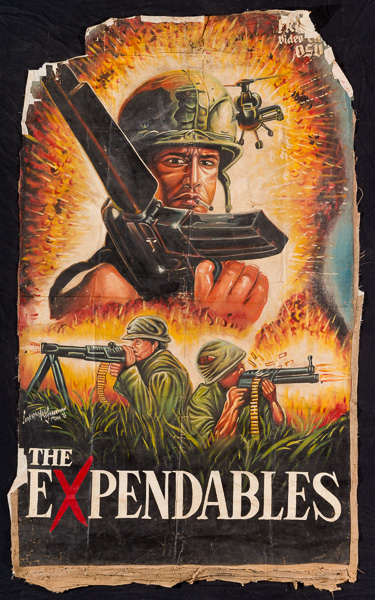

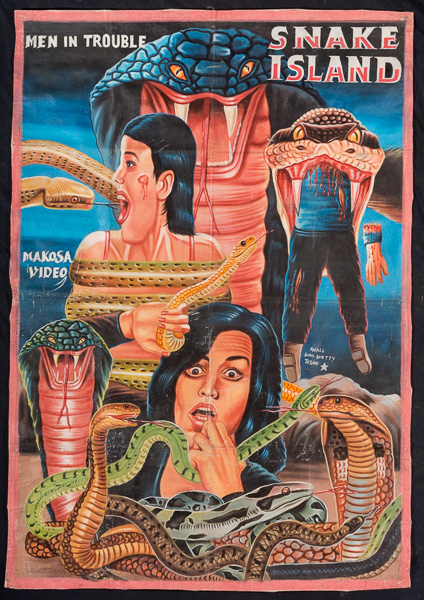

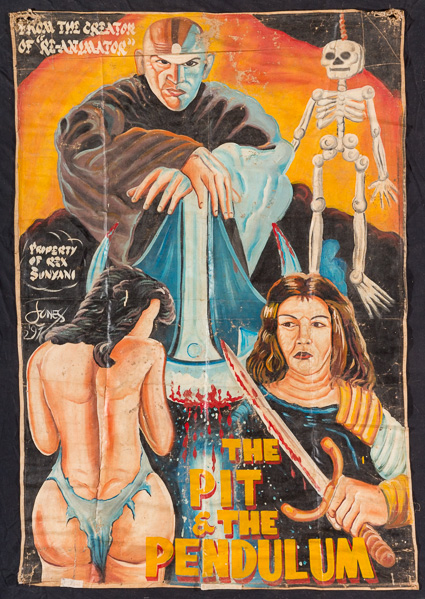

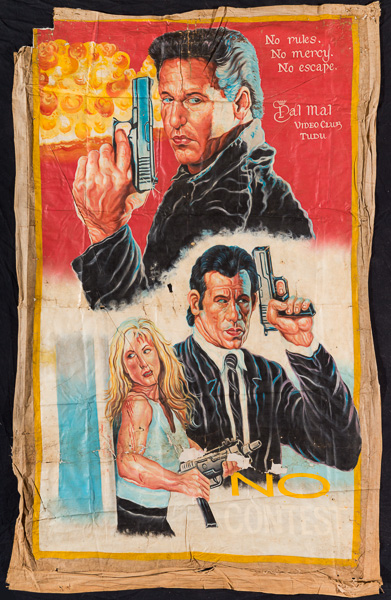

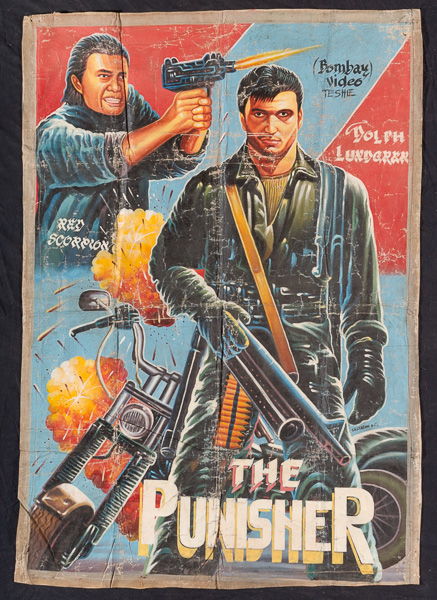

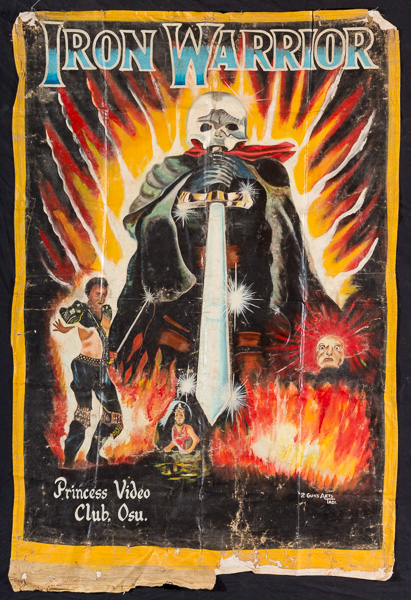

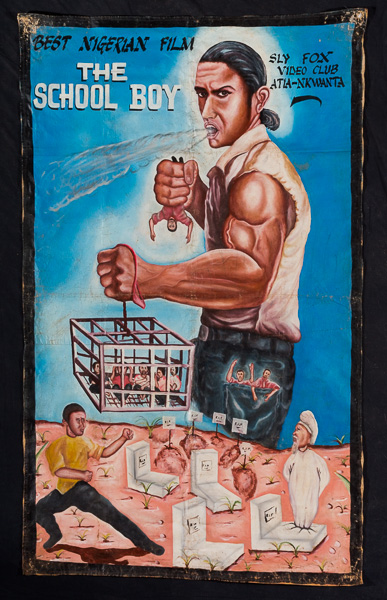

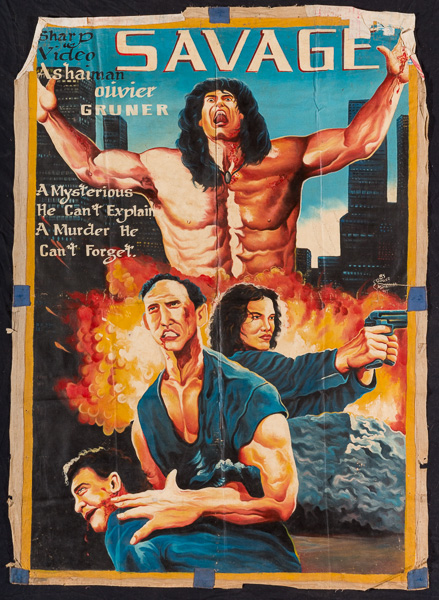

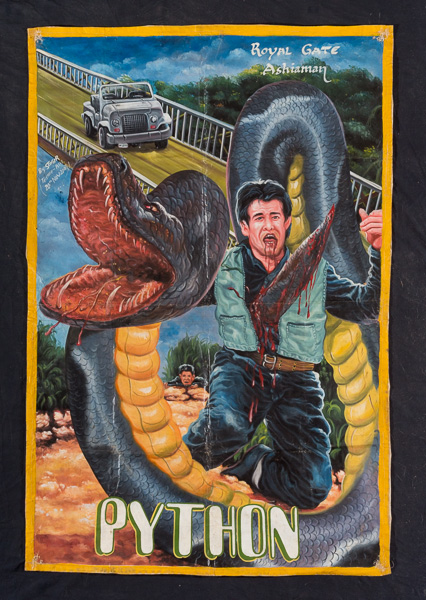

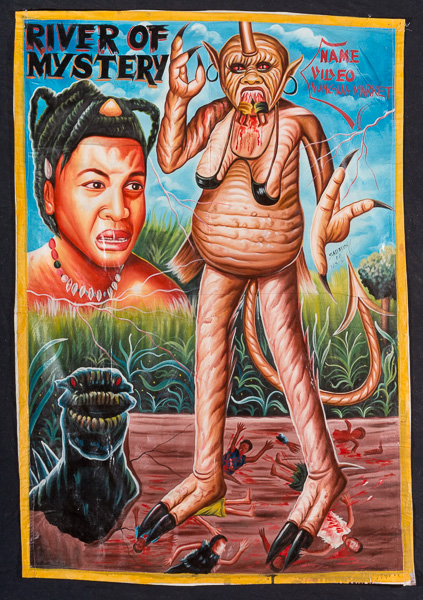

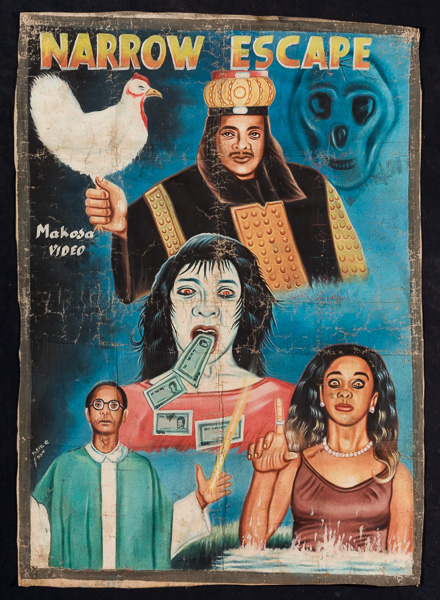

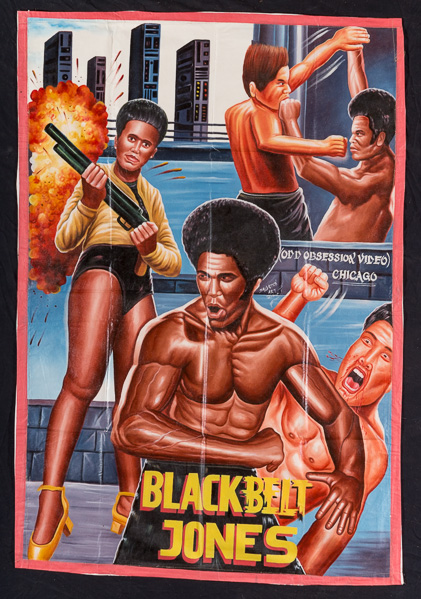

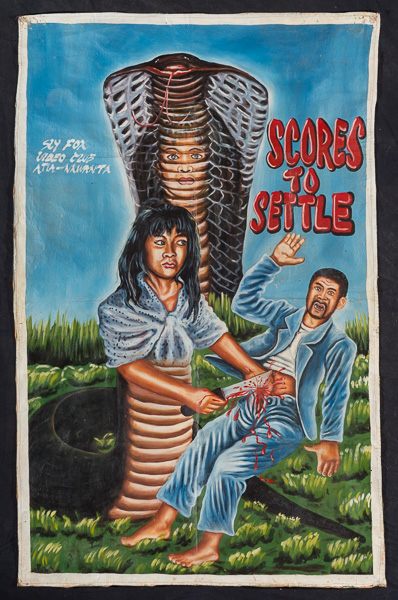

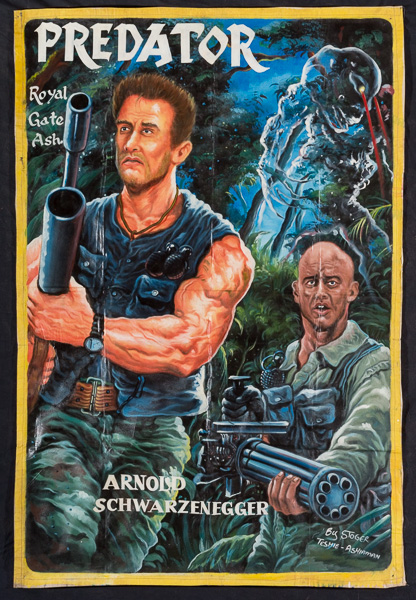

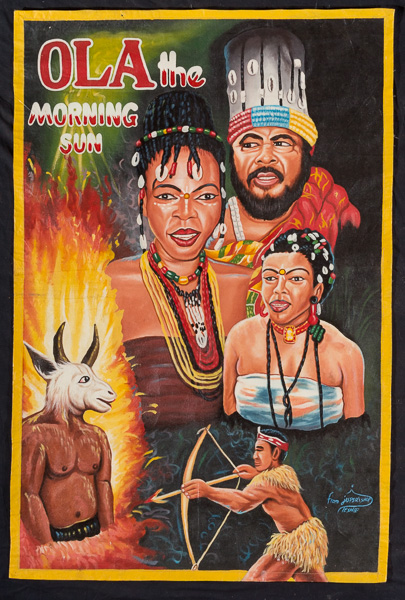

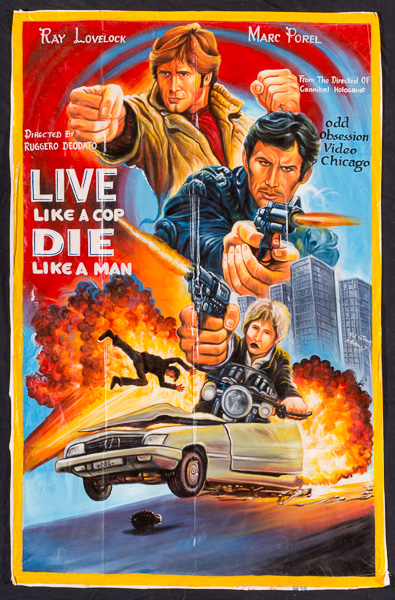

“The late 1980s in Ghana saw the emergence of exuberant new visual modes of expression in a new local and innovative film industry (alongside that of Nigeria commonly referred to as Nollywood), especially in the ways films were promoted by vivid hand painted posters on sack or canvas.

Highly skilled artists emerged to create striking images with their surfaces co-ordinated in eye catching colour arrangements to command the attention of passers-by. These film posters were commissioned by mobile local entrepreneurs taking the films to a range of communities and using the cloth posters that could be rolled up, unfurled and transported very easily as they criss-crossed the country. The intense competition between films enhanced the creativity and imaginative possibilities realised by the artists in the film posters and established their individual renown.

These dramatic and highly charged images, usually some six or seven feet high, were conspicuously displayed by the roadside or in prominent public positions to alert filmgoers to the release of new films. Many of these films were made locally in Ghana or imported from the Nollywood film industry of Nigeria. Their iconography emphasised the melodramatic, combining a blend of elements that drew on the local beliefs that intersected with the range of popular imported films, such as the imagery of America’s Hollywood and India’s Bollywood that were also shown in Ghana”.

Text from the exhibition at Brunei Gallery, London, January 2019, entitled

“African Gaze: Hollywood; Bollywood and Nollywood film posters from Ghana” curated by Karun Thakar, London, England

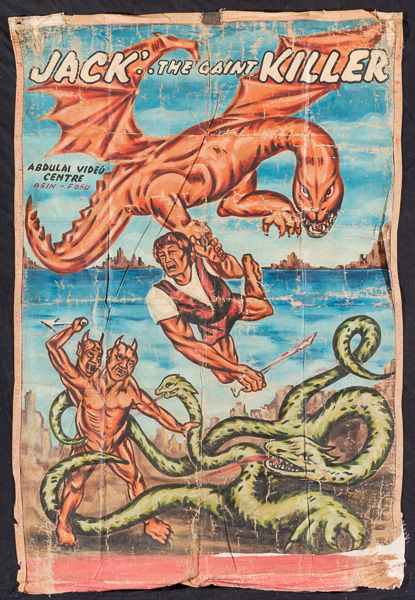

These posters were once the product of a much larger industry known as the “Ghanaian Mobile Cinema”. This business started in the late 1980’s when artistic industrious groups of people formed video clubs. With a television, vcr, vhs tapes, and a portable generator they’d travel throughout Ghana setting up make-shift screening areas in villages void of electricity. An interesting selection of movies became popular because of this trade includeing both Hollywood action and horror, low budget American schlock, Bollywood films, Hong Kong martial arts movies, and native Ghanaian and Nigerian features.

As more people gained interest in this rising business, competition arose. Mobile cinema operators found a need to set their products apart, so an advertising motif came into play. With no affordable access to printing, the hand-painted movie poster was the most logical advertising vehicle. Skilled local artists were now part of this growing entertainment industry in Ghana, and they surely brought their own distinct touch to each film they were called upon to promote. By sewing together two used flour sacks, a perfect sized canvas for a movie poster was created. Each unique poster varies in size ranging from 40 – 50 in. width x 55-70 in. height. The ruggedness of these posters is immediately noticed. Though a specific poster might only be 10-20 years old, it’s appearance will far surpass it’s actual age due to the elemental toll one takes from constant transit, being rolled, folded, left in the sun, rain, etc.

Today access to printing is far less expensive and movies have become more accessible to the general public in Ghana. The mobile cinema has all but passed away, but these hand-painted movie posters remain a wonderful, tangible product of the time.

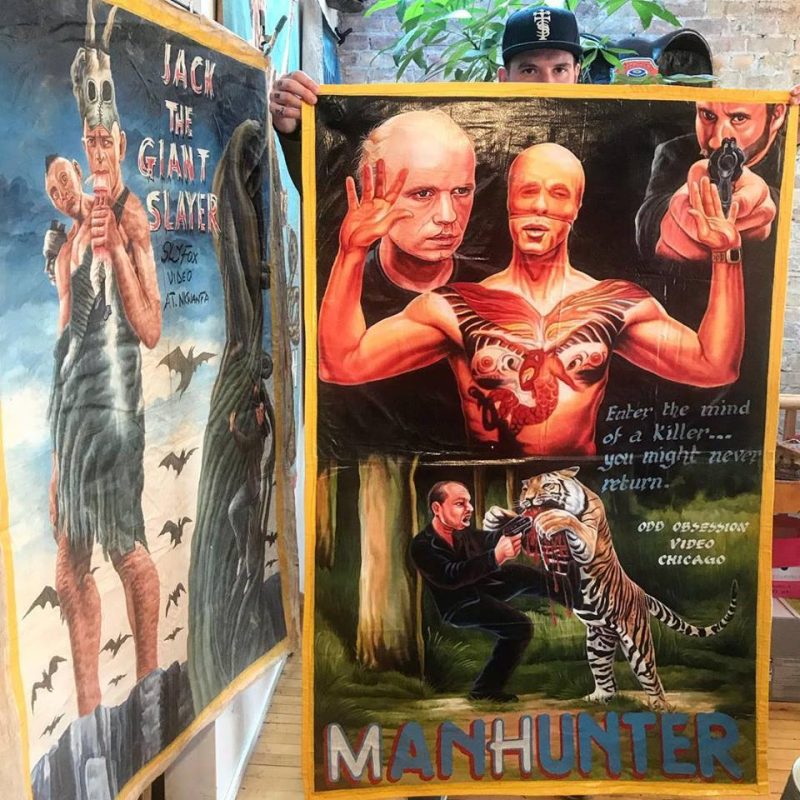

Deadly Prey Gallery is a space dedicated to West African poster and sign art created by brother & sister duo Brian and Heidi Anne Chankin. Brian is also the owner and founder of Odd Obsession Movies, a video store in Wicker Park specializing in genre film, foreign, classic, and independent cinema.

————————————————————

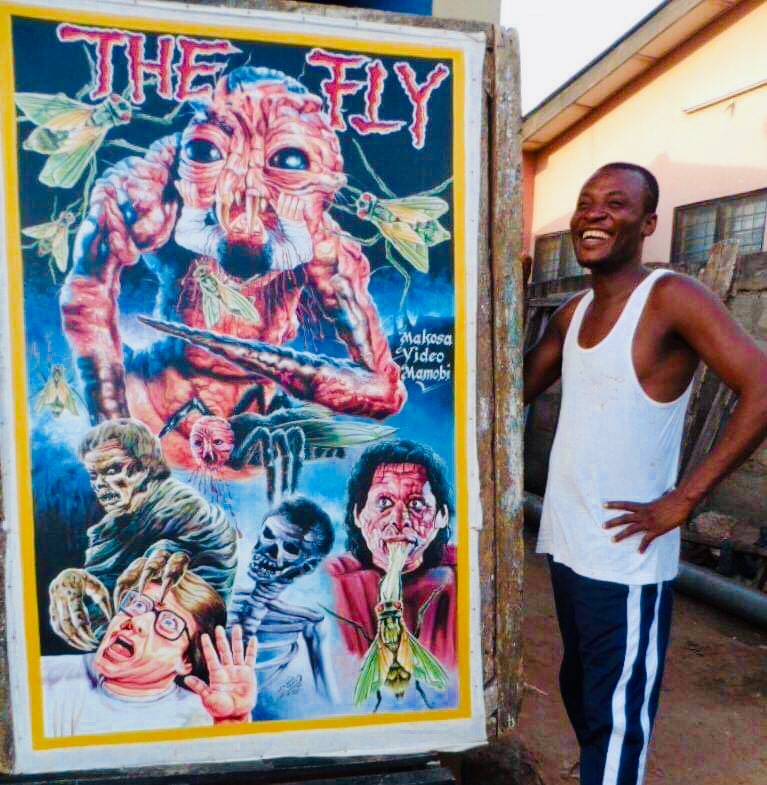

HEAVY JAY: featured artist

Jeaurs Oko Afutu, with his artist name as Heavy Jeaurs or Heavy J. Heavy Jay, was born in 1975 in Teshie a suburb of Accra, the capital of Ghana. In 1988 he worked as an apprentice under Ras Portey an elderly artist in Teshie, he later attended the Ghanatta School of Art for a period of one year.

Between the period of 1988 to 1995, he graduated as a professional sign painter and then opened a painting studio in Teshie in 1996. In the 1990s, the sign writing business was not fetching enough so he decided to focus mainly in the production of hand-painted movie posters for the local cinemas in Accra and other video clubs and rentals across the country.

Due to the declining of the cinema and the video club business for the past ten years, he has been painting for commercial sales by way of commissions for individual lovers of the art and some private art collectors worldwide

————————————————————-

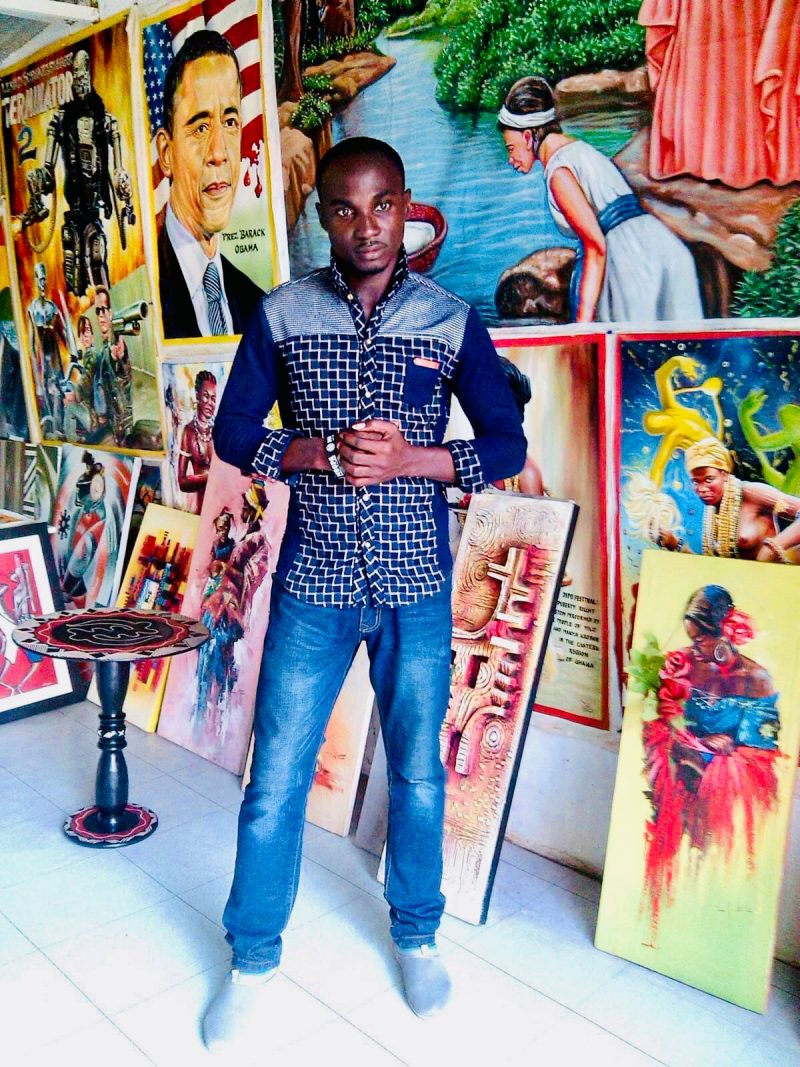

STOGER: featured artist

Stoger, known in private life as Benjamin Tawiah Armah Amartey was born in 1972 in Accra, he discovered his artistic talent at a very tender age, while in school, he realized he was doing much better in drawing than all the subjects so he became more interested and paid more attention to his drawing prowess.

He later left school and enrolled in an apprenticeship with his elder brother who was also an artist. Stoger became better in drawing each and every day and improved in his painting skills and also gained more knowledge about painting.

After three years he graduated and became a professional artist and begun painting movie posters for the local video clubs all over Ghana from the early 90s till now.

———————————————————

KOFI: Partner & intermediate in Ghana to Deadly Prey Gallery, Chicago

Robert Kofi Ghartey was born in Winneba, a coastal town in the central region of Ghana but grew up and started my early childhood education in Elmina. Due to the health condition of my father, we left Elmina back to Winneba in the early 90s and continue my education until I lost my father in 1996.

That same year was when I also left Winneba to Accra, the capital to pursue life and continue my education due to the hardship my family was facing after the demise of my father. I am the seventh child out of nine and the only standing breadwinner of the family.

Currently, I am a freight forwarder, a drum maker, a lover of all kinds of art and the owner of G. ORIGIN ART GALLERY located at the Center for national culture in Accra Ghana. The last thing I want to achieve in life before I die is to own a very reputable orphanage home to give care, education, and impact the lives of the less privileged from children to the aged. I am single but have one adopted daughter.

————————————————————

Recent Press:

Baptized By Beefcake: The Golden Age of Hand-Painted Movie Posters from Ghana

https://indyweek.com/culture/art/the-wondrous-movie-posters-of-ghana-s-underground-video-club/

https://www.itsnicethat.com/articles/karun-thakar-ghanaian-film-posters-exhibition-graphic-design-180319

Hollywood movie posters as you’ve never seen them before

http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20190313-incredible-ghanaian-film-posters

Dazzlingly Morbid, Hand-Painted Film Posters from 1980s Ghana

The Wondrous Movie Posters of Ghana’s Underground Video Clubs Come to NC Comicon

MAR. 13, 2019

Photo by Brian Chankin

Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai poster by Heavy Jay

By and large, modern movie posters are boring. They’re usually just a still showcasing a few characters and special effects, or the lead actors’ faces blown up to a massive size that makes it impossible to tell what the film is about.

But necessity is the mother of invention, a truism that, in Ghana, resulted in some of the most inventive movie posters ever. Staring in the 1980s, in remote Ghanaian villages, films circulated through underground video clubs with a VCR and an electric generator. These screenings were promoted with posters painted on flour sacks by artists who sometimes had only the VHS box art for reference. The result was a bounty of massive, colorful, often surreal posters that have become cherished by collectors and spawned a market for new commissions. This weekend, a renowned collection of them is heading for NC Comicon at the Raleigh Convention Center, as part of a slate of collaborative programming with Alamo Drafthouse.

Brian Chankin, the owner of Odd Obsession Movies, a cult-video store in Chicago’s Wicker Park, turned his fascination with Ghanaian movie posters into a second business with his sister, Heidi Anne. Deadly Prey Gallery specializes in vintage original posters as well as commissions from artists in Ghana, including some of the underground luminaries from the video clubs’ nineties heyday. In advance of Deadly Prey’s trip to NC Comicon, we spoke with Chankin about his passion for movie memorabilia, the culture behind the posters, and how a no-budget cult action film gave his gallery its name.

INDY: How did you discover Ghanaian movie posters?

BRIAN CHANKIN: A friend of mine brought in a book of the posters, and I freaked out. I thought, “This is the coolest thing I’ve ever seen!” I think it helped that people know I like weird movies and collecting weird movie stuff. From there, I just started researching and collecting.

When were these posters just made for video clubs, and at what point did commissions become a thing?

The video clubs started in the early eighties. By 1986, the first posters were being painted by artists like Joe Mensah and Leonardo. The last traveling posters I’ve seen are from around 2007, but by 2000, many poster artists were already making the posters as art alone, and also taking commission projects. I think commissions have been a thing since the beginning. It’s just that in the eighties and nineties, it was video clubs commissioning the posters and paying the artists.

When it comes to the vintage posters, are the artists who created them known today?

There were probably more than seventy-five artists making these posters in their heyday. We work with seven of the artists from the nineties, and there’s maybe eight more who run their own business. Many of the artists sell their work to dealers and traders in Ghana these days, for good prices, after years of being taken advantage of. The prices for commissioned and new work have gone up steadily, I’m happy to say. Unfortunately, many of the past artists are difficult to get ahold of. After 2000, many of them simply moved on from making posters because of the drop in business. Many of those same works, however, are not for sale. They are in my permanent collection of posters that will someday find themselves back in Ghana to be archived.

Do you have any famous clients you can talk about?

I can tell you that there are some actors, like Stallone and Schwarzenegger, who bought a lot of these. Not from me. [Laughs] Arnold, I know, bought a lot of the super, super old and expensive ones from Ernie Wolfe III, who did the book Extreme Canvas about the Ghana posters. There’s an interview where Stallone is talking about how he has a Cliffhanger poster from Ghana from the nineties. A lot of my own clients have been people in the tattoo community. Action Bronson’s bought a number over the years, and he found out it about it through other people in the tattoo community. It’s been a surprising variety of clients.

A lot of artists do movie-poster prints of different films out of fandom, but these came out of necessity.

Right. I’d say, over time, it came to be both: fandom andnecessity. Some of these artists have painted so many of these titles over the years that they’re very familiar with certain films, despite having only seen parts of the film or the VHS art. If twenty different people ask someone to do a poster of Big Trouble in Little China, even if they’ve done it many times before, you’re still going to get twenty different posters, and all of them are going to be amazing.

One of the most popular titles people ask me for is Star Wars, and of course, you can commission one. But if you want to find an old one, you can’t—there were almost no VHS tapes of the original movies in Ghana, because they had copy protection and were almost impossible to bootleg. Things like that dictate which movies would become popular in Ghana. It’s directly responsible for how I got the name Deadly Prey.

That film was popular … anywhere?

Deadly Prey is obviously a cool movie and has its own fan base in the bad-movie realm, but in Ghana, I feel it can stand side by side with The Matrix and Robocop and The Terminator as this kind of sublime American action movie that is thought of as part of the larger popular culture.

You also have some posters for films made in Africa.

A lot of those are horror films, often with a religious bent. The main character is usually a pastor, and the bad guy is usually the devil. There aren’t as many posters for films that are dramas, because they aren’t as sensational.

What are some elements that contribute to a memorable Ghanaian film poster?

It actually helps if the title can be interpreted in different ways. We did a commissioned poster for Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai recently, and the artist drew Forest Whitaker fighting a bunch of dog ghosts with a samurai sword.

What all will you bring to NC Comicon?

We’ll have around two hundred and fifty originals, the most we’ve ever brought to a show, and if you’re interested in getting a commission from an artist in Ghana, we can talk to you about costs and setting things up.

How do you acquire these posters?

Well, I’ve been collecting them for about eight years now, and doing Deadly Prey for the last five years. I was doing commissions and stuff just on my own, which I set up with my partner in Ghana. I mostly work through people I’ve networked with over there. I am planning to go, however, right after NC Comicon. My partner in Ghana, Kofi Gharety, whom I’ve been dealing with for the whole eight years—we’ve talked on the phone, emailed, texted, but we’ve never met in person. So that’s going to be amazing, getting to see him for the first time. I can’t wait for that day.

arts@indyweek.com

“““““““““““““““““““““““““““““““

What is the Spirit of the Beehive:

(Spain, 1973, 97 minutes, color, 35 mm)

Directed by Victor Erice

Cast:

Fernando Fernán Gómez . . . . . . . . . . Fernando

Teresa Gimpera . . . . . . . . . . Teresa

Ana Torrent . . . . . . . . . . Ana

Isabel Telleria . . . . . . . . . . Isabel

The following film notes were prepared for the New York State Writers Institute by Kevin Jack Hagopian, Senior Lecturer in Media Studies at Pennsylvania State University:

In 1973, the year of The Spirit of the Beehive, the Francoist regime in Spain was rotting from the inside. Its leader was frail, probably dying. Democracy waited just beyond the door of the death chamber, pacing anxiously and looking at its watch. It had been a long time since the murder of the Second Republic in 1939, and Spaniards were impatient.

Franco’s rule was borne amidst multiple and hideous violations of human rights and the quashing of civil liberties. Political speech had been restricted for so long that one was no longer sure what it meant to `speak politically’ in Spain. Instruction came from an unlikely corner: the arts. Through satire, allegory, ellipsis, and occasionally, out and out criticism, resident painters and novelists and dramatists sought ways to speak the truth about Franco’s fascism to Spain and the world while avoiding becoming among the disappeared.

Filmmakers in such restricted societies as Franco’s Spain have always been among the most ingenious in subtly expressing resentment and rejection of intimidation, whether the Prague Spring and Eastern European filmmakers who satirized the Soviet Union, or Fifth Generation Chinese filmmakers who have softly but insistently criticized the regime, or the contemporary Iranian feminist cinema, undercutting institutionalized sexism. So it was with filmmakers in the latter Franco years.

The tone was set by Spain’s greatest filmmaker, Luis Buñuel. In exile since the Civil War, he returned to shoot Viridiana there in 1962. Somehow, this anti-clerical parable passed the state censors, whose minds were apparently not very supple. The Franco regime was intimately tied to the Catholic Church, and Buñuel had been smacking the Church for many years in the cinema. Buñuel, a skilled and eloquent fabulist in word as well as image, got away with it, and was out of the country before the world began informing Spain that it had been sorely duped.

Buñuel’s example wove itself into the lives and art of a new generation of Spanish filmmakers, led by Carlos Saura, a teacher at the National Film School in the 1960’s, and godfather to a new wave of Spanish cinema. Mario Camus, Jose Luis Borau and Manual Gutierrez Aragon were among the directors incubated in this moment of political and cultural transition. Victor Erice’s The Spirit of the Beehive, however, more than any other single film in the wake of Viridiana, announced to the world that the culture of Francoism, if not its dictatorial military power, was vulnerable. Borrowing from Buñuel, Erice and his collaborators raise an allegorical question mark that begins with the film’s opening gambit: “Once upon a time…” leads us, not to some timeless neverland, but to Spain in 1940, at the moment of its plunge into despair.

The beehive is the film’s totem of a troubled Spanish society, in Marvin D’Lugo’s words, “a symbol of a social order which, while superficially unified, is nevertheless marked by a radical isolation of each of its members from one another.” Such, argues Erice, has been the deep psychological cost of the Civil War and its following decades of repression. Fernando (Fernando Fernán Gómez) tends the bees, and his family lives nearby, in unconscious impersonation of the apiary. The family and its unreflective, repressive structure are challenged, not by a political rally or an act of terrorism, but by the sublime subversion of the cinema. In Fernando’s sleepy Castilian village, the only excitement is stirred by the movies, a fantasy realm to which the villagers devote themselves, desperate for an imaginative alternative to the dry routine of their days. One Saturday, a particular film, James Whale’s striking Frankenstein, is shown in the town hall. For Fernando’s daughter, Ana (Ana Torrent), the film erupts from the screen, shattering the smooth surface of her days, and tossing her into a series of mystical adventures and hallucinations which offer themselves as a kaleidoscope of exciting, incredible alternatives to the dull mental regimentation of Francoism.

Now surreal, unmoored, and odd, The Spirit of the Beehive careers from one strange vision to another, the fantasies of Ana and her circle always in contrast to the spirit of the beehive. This is a Cinema Paradiso for the anarchists among us, a testament to the liberating power of art, and a courageous, smiling indictment of conformity and hypocrisy.

— Kevin Hagopian, Penn State University

PLEASE NOTE :

The exhibition of film posters from Ghana CONTAINS IMAGERY OF NUDITY, VIOLENCE AND THE ‘OCCULT’ THAT SOME VISITORS MAY FIND DISTURBING OR OFFENSIVE