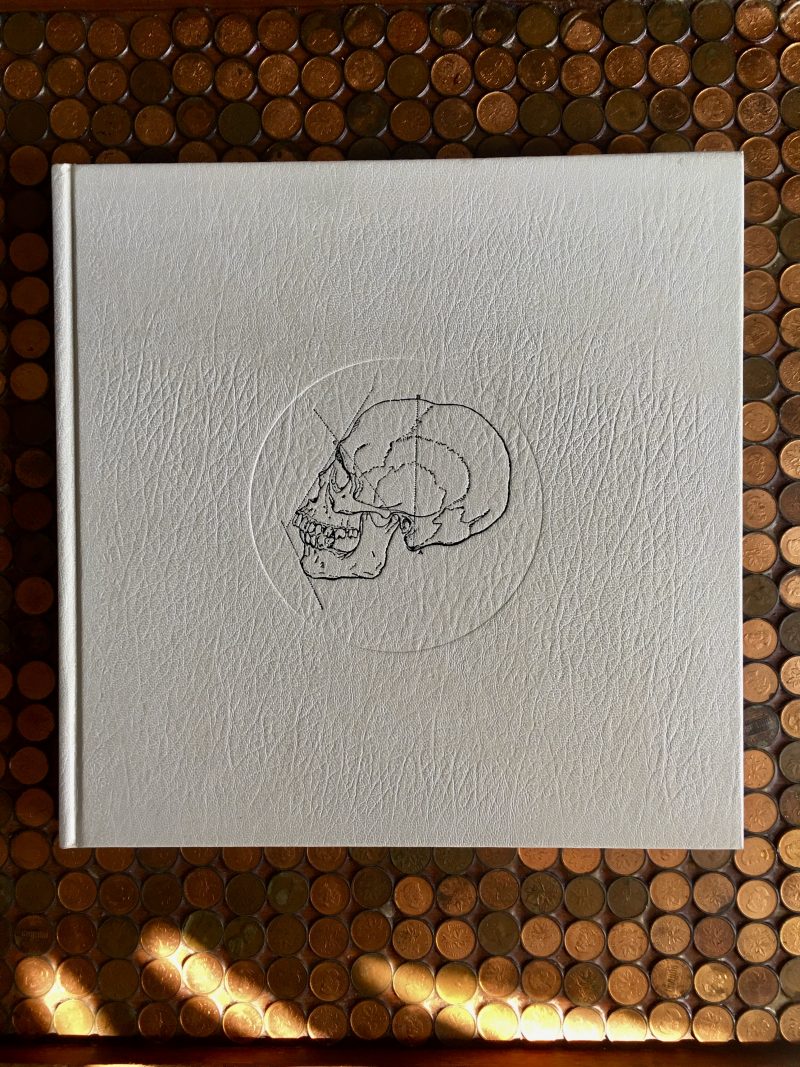

Ghost in the Shell: Photography and the Human Soul, 1850-2000

Ghost in the Shell: Photography and the Human Soul, 1850-2000

Essays on Camera Portraiture

322 pages, Hardcover

First published November 19, 1999 / First Edition

About the Author

This Edition

Item Weight : 4.74 pounds

Dimensions : 11.5 x 1 x 11.5 inches

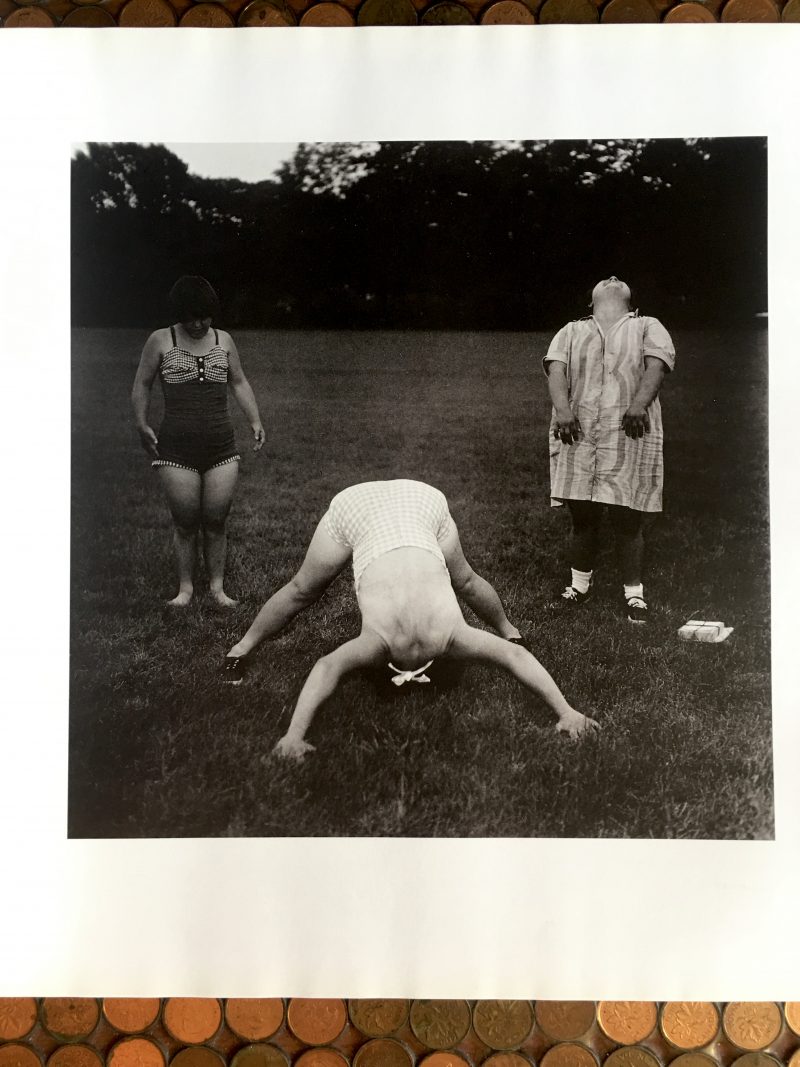

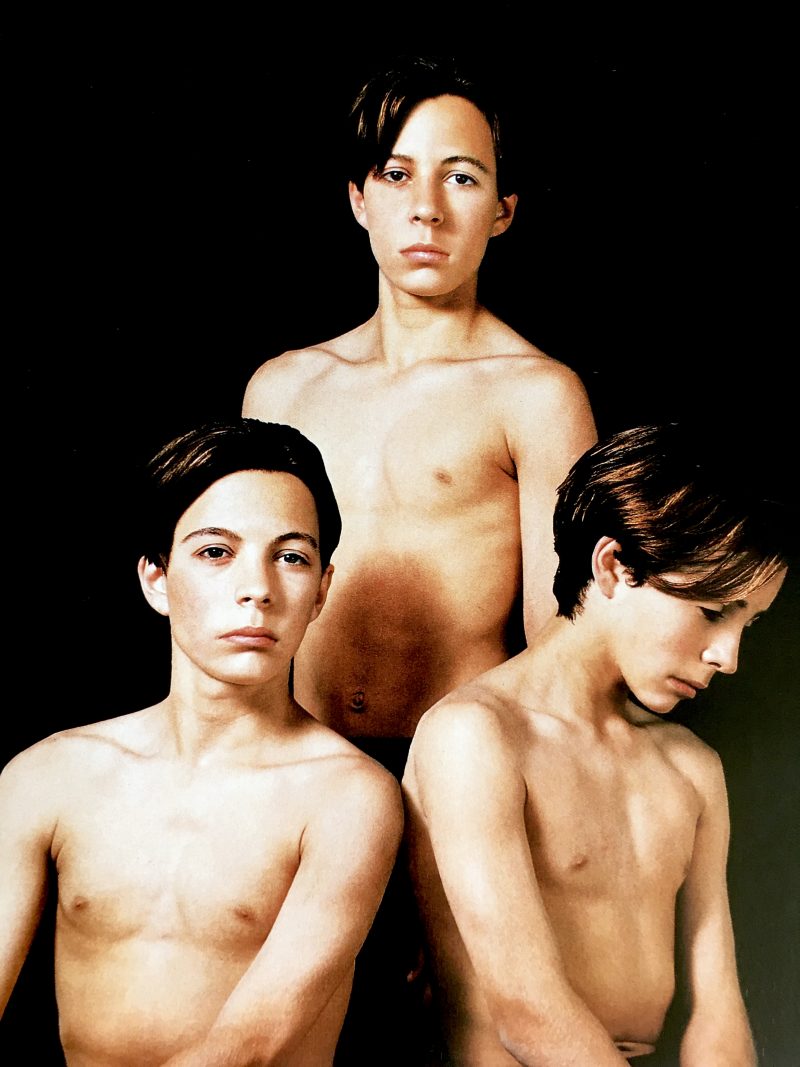

Ghost in the Shell takes as its premise the idea that the outer person is a reflection of the inner. Tracing the modern photographic portrait over the past 150 years, the book reveals the many ways the photographic arts have investigated, represented, interpreted, and subverted the human face and, consequently, the human spirit. Artists have used the genre not only to convey familiar emotions such as fear, love, sadness, and anger, but also to explore complex subjective states such as passionate individuality and psychological withdrawal. Different avant-garde movements have enlisted farce, masks, and masquerade in their charting of the human character, and many postmodern works employ irony and ambiguity to deal with issues of identity, gender, and dissociation.

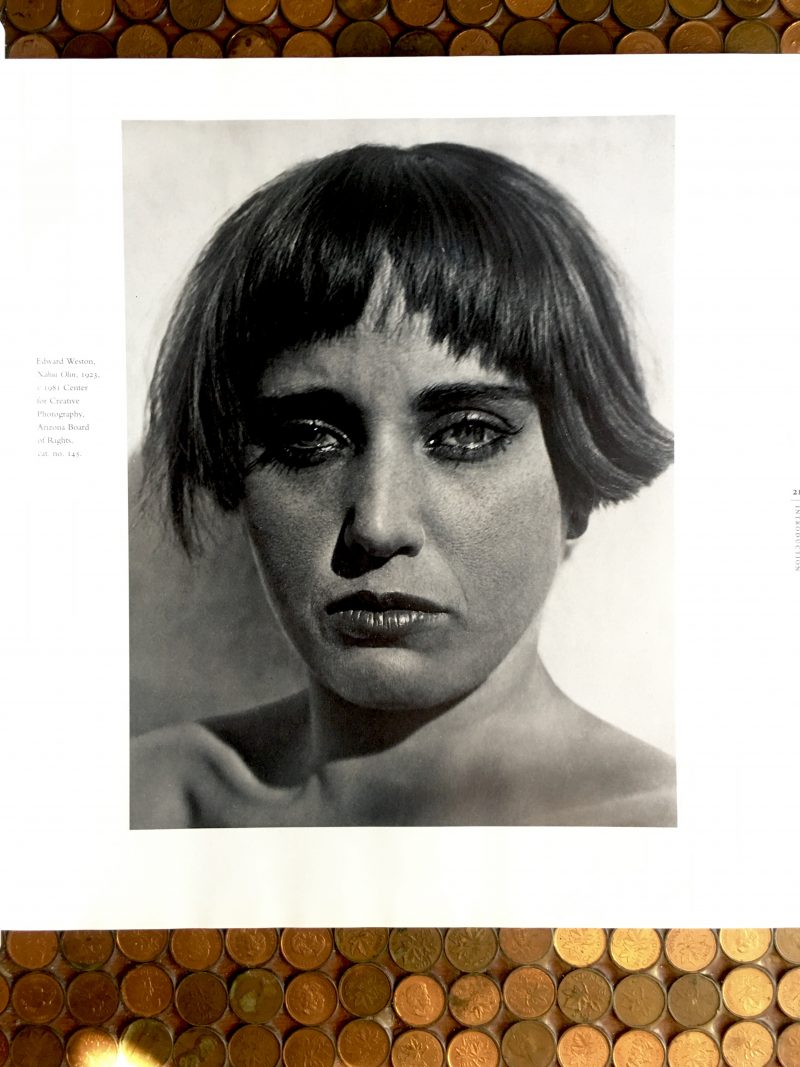

The book, which accompanies an exhibition opening at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in October 1999, is organized roughly chronologically around the traditional, modernist, and postmodernist views of the face, although the primary approach of one period often appears in the others. The artists discussed include, among others, Diane Arbus, Julia Margaret Cameron, Edward Curtis, Salvador Dali, Duchenne de Boulogne, Dorothea Lange, Annie Leibowitz, Bruce Nauman, Orlan, William Parker, Irving Penn, Lucas Samaras, Cindy Sherman, Andy Warhol, and Edward Weston.Published in cooperation with the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

REVIEW:

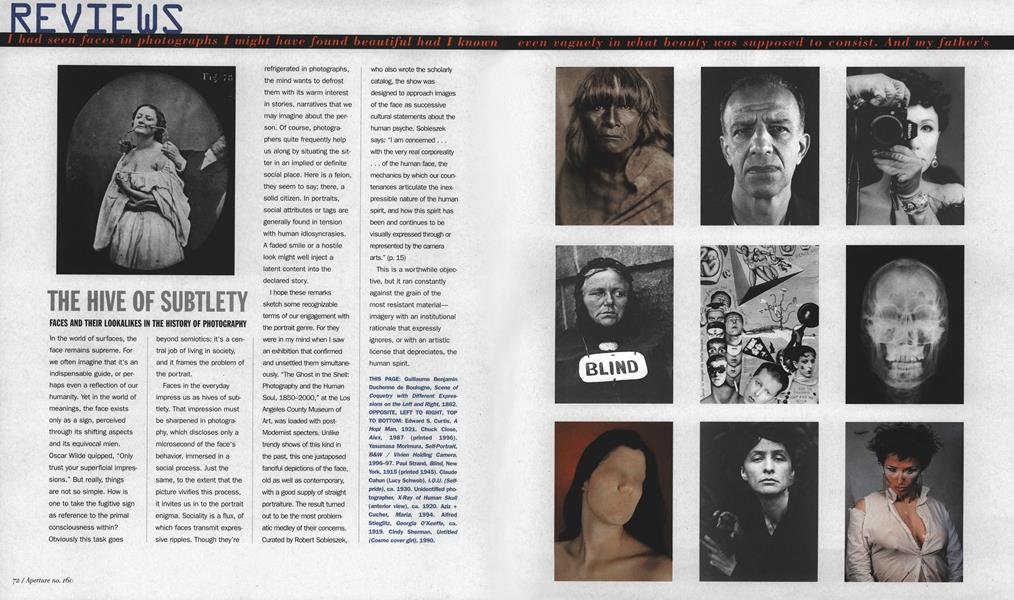

The Hive Of Subtlety

FACES AND THEIR LOOKALIKES IN THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY

Summer 2000

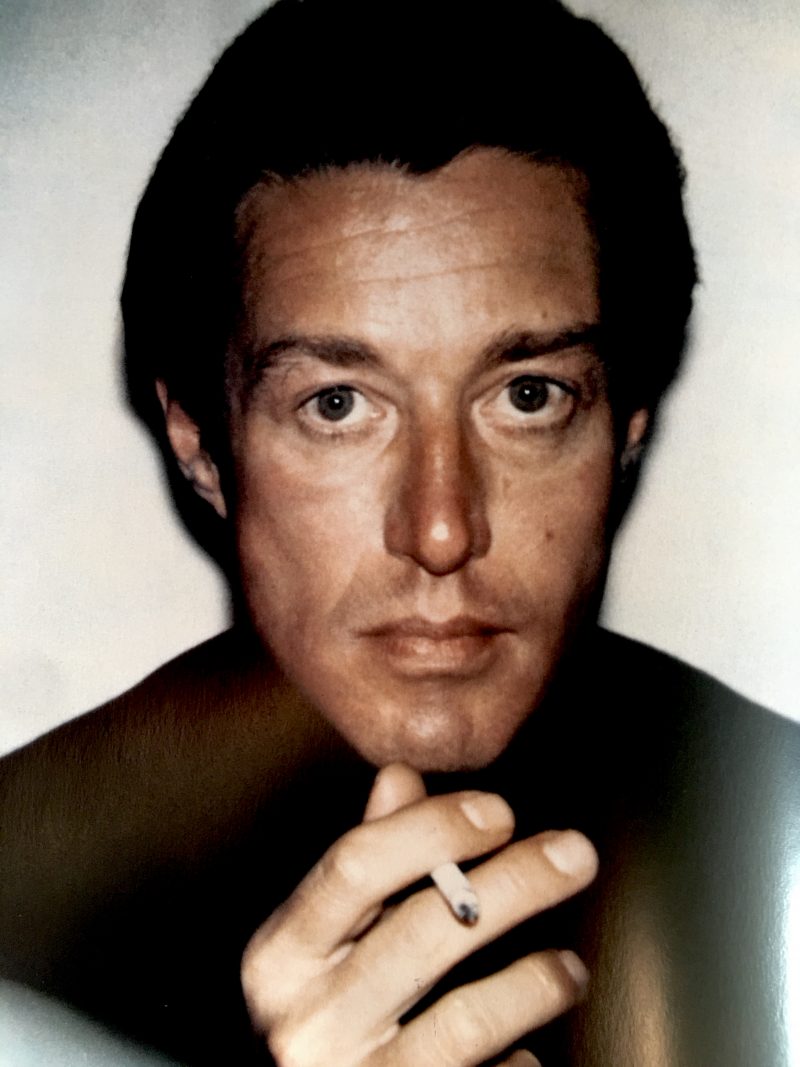

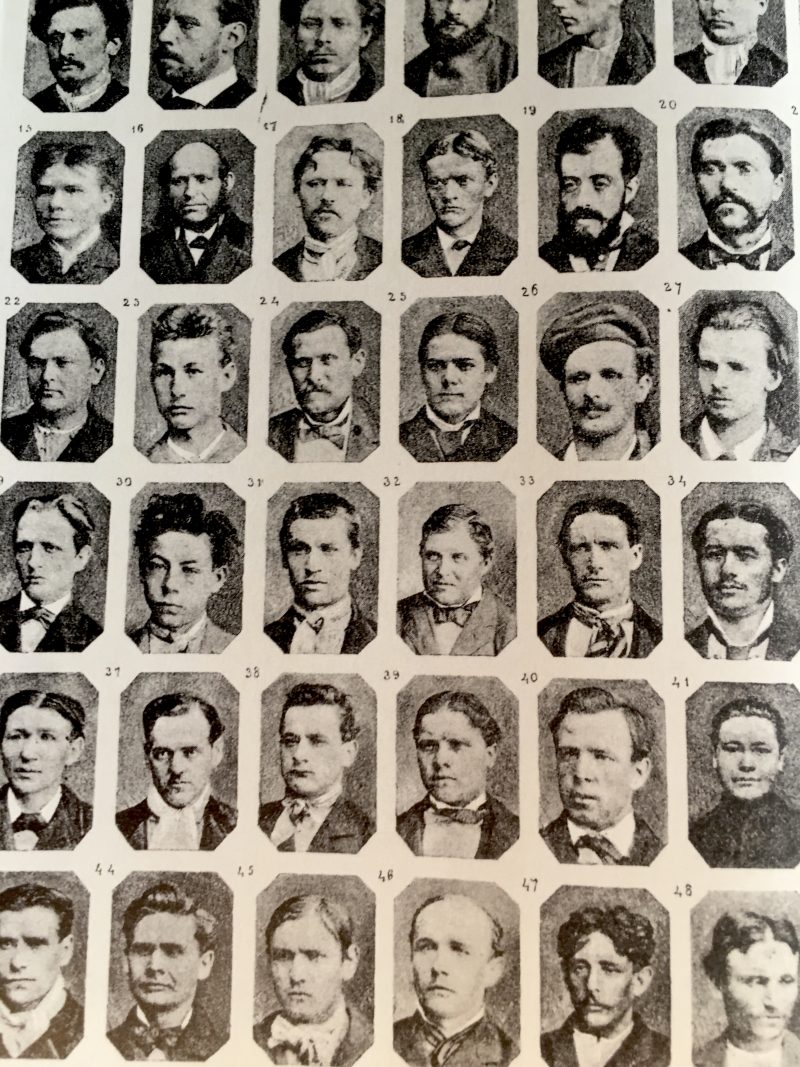

Sobieszek’s second essay in the catalog, having a different story to tell, links the scientific with the artistic misadventures of the face. He centers here on the work of Andy Warhol, who eulogized the leveling influence of the media upon personality. Walker Evans considered nameless faces with his vernacular spirit, infused by a democratic ethos. Sobieszek quotes William Carlos Williams on Evans: “We see what we have not heretofore realized, ourselves made worthy in our anonymity.” Warhol, for sure, approached his subjects in an antithetical spirit. Mostly celebrities, he treated them as interchangeable and degraded icons. You can say that Warhol had an antidemocratic outlook: we are “worthy”—if that is still the word—only in our uniformity, a state promoted by the replacement of popular culture by mass culture. Evans had implied that our diversity contributes to our common enterprise. (As in his photograph of a commercial portrait studio’s products, gridded in its window.) Warhol, for his part, imagined that the social good would be realized only once the diversity of our preferences has been eliminated. This is a contrast between Evans’s democratic principle and an authoritarian dream.

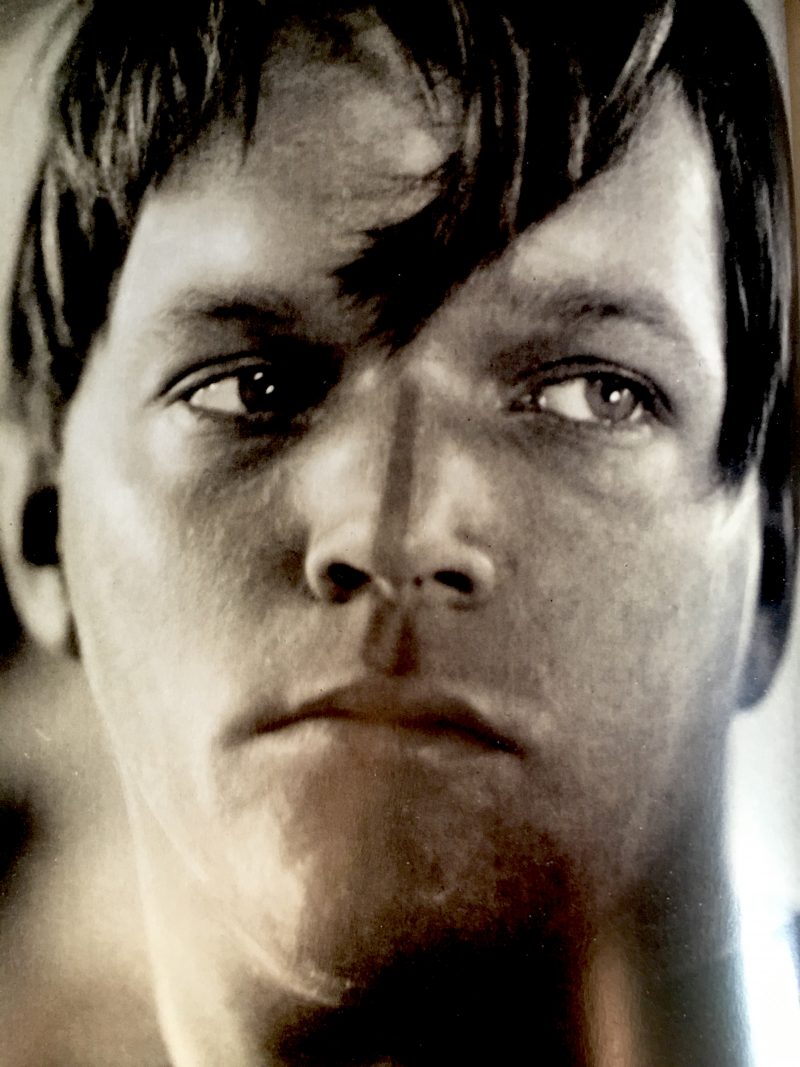

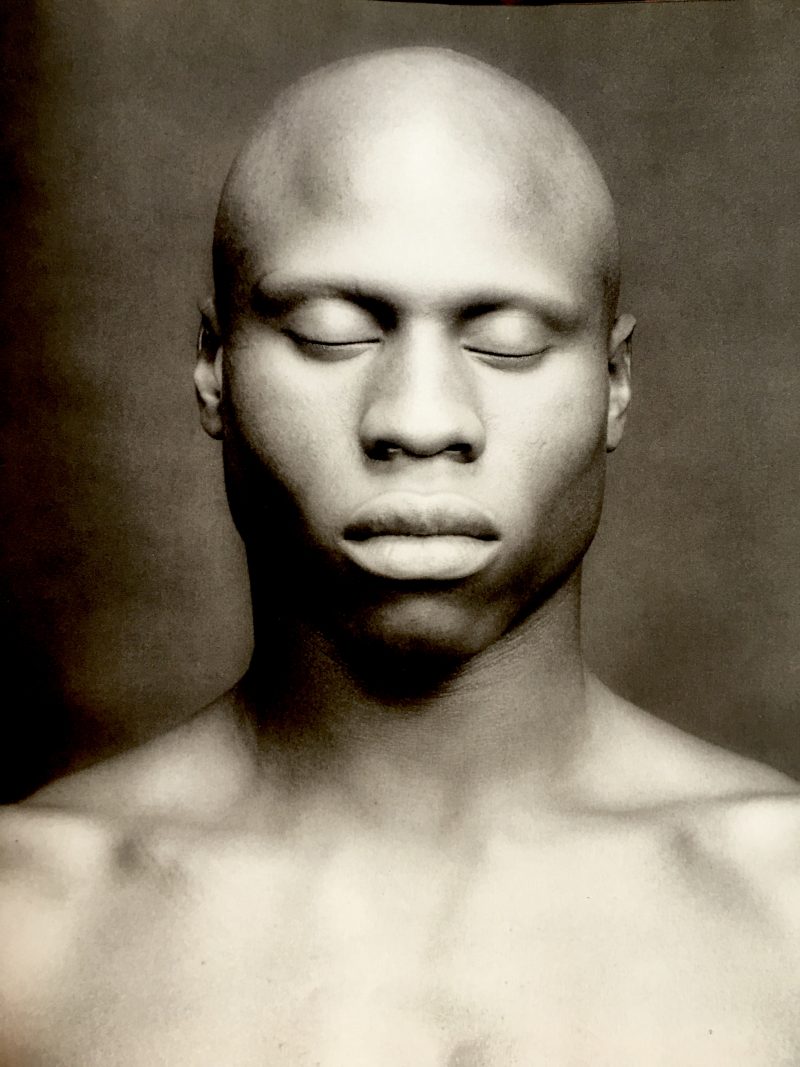

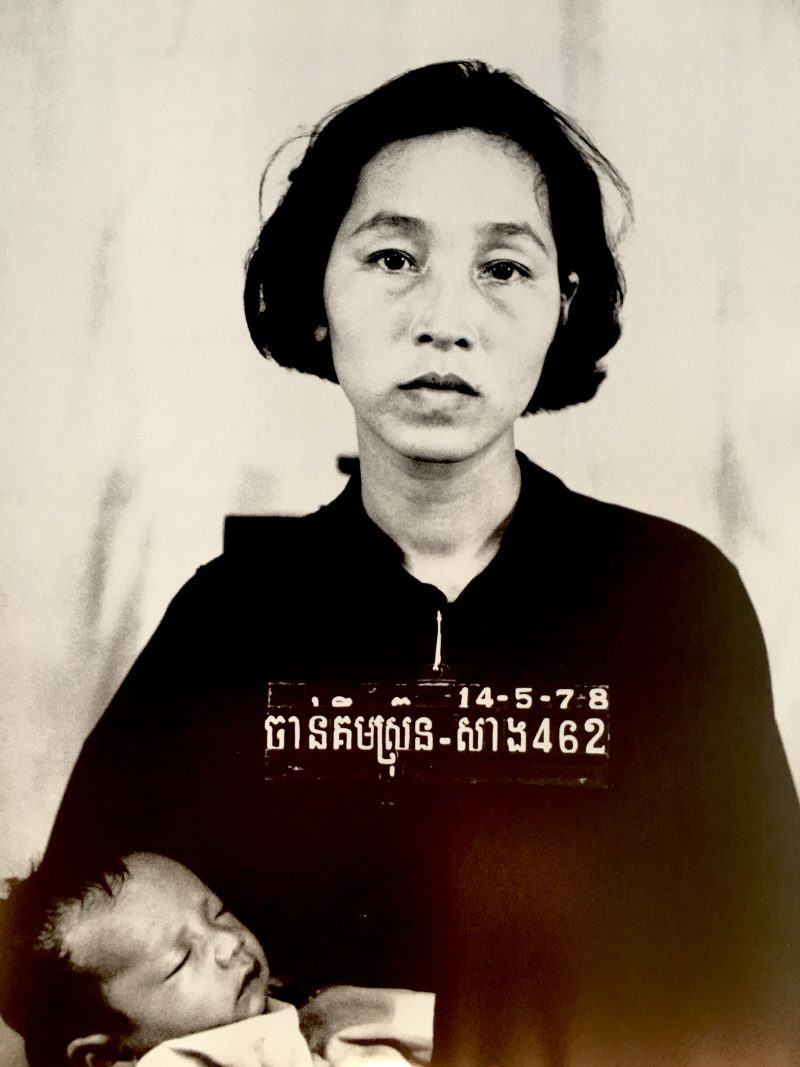

What followed in Modernist portraiture deserves to be called archaic. I refer to the effect of the stiff, frontal poses and the pre-psychological primitivism in the work, say, of Chuck Close and Thomas Ruff. With the mug shot, you merely reckon with a standard maintenance of distance from the personality of the subject. With Close and Ruff’s similar though over-life-size and evidently processed art, we have to deal with an offhand dispossession of humanity. It’s as if the “who-ness” of the subject were a condition either too sentimental or too conjectural to get worked up about. Sobieszek approvingly quotes J. M. Ballard: “the most terrifying casualty of the century [is] the death of affect.” One sometimes wonders if artists like Close and Ruff have thought enough about the difference between commenting upon this deathly aspect of the Zeitgeist and being a party to it.

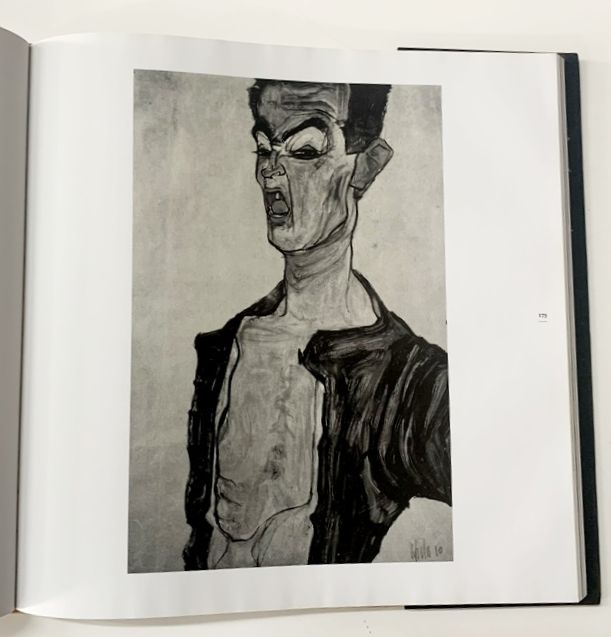

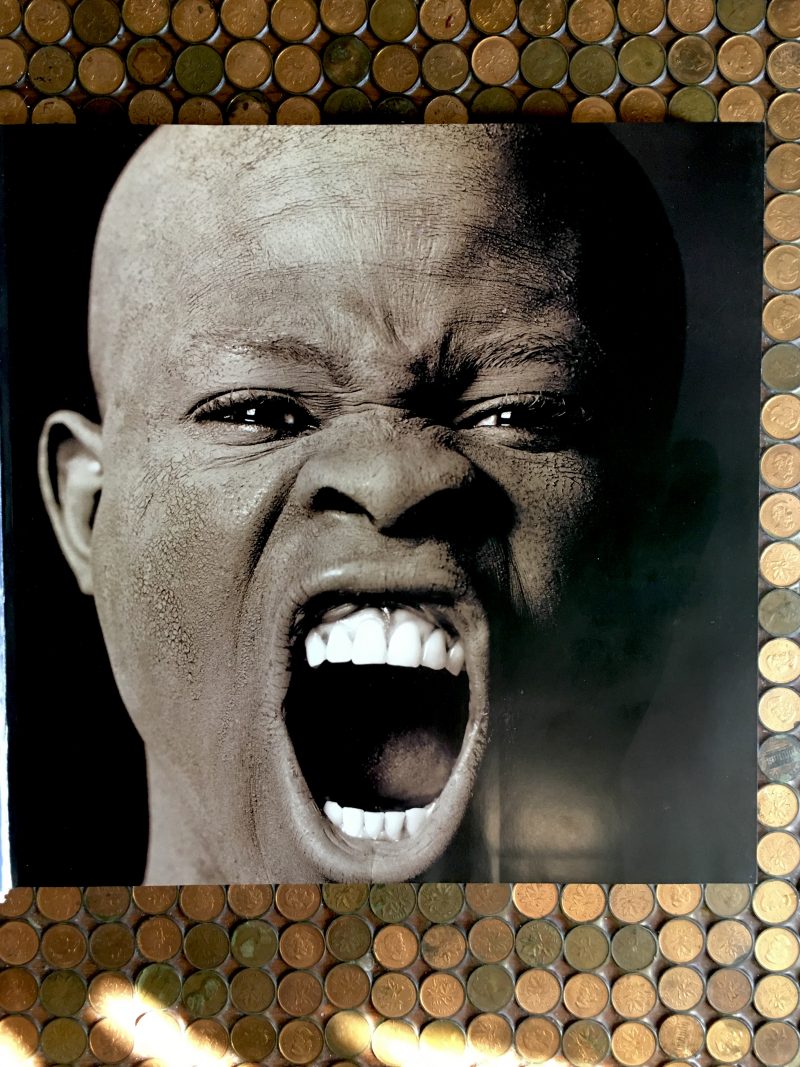

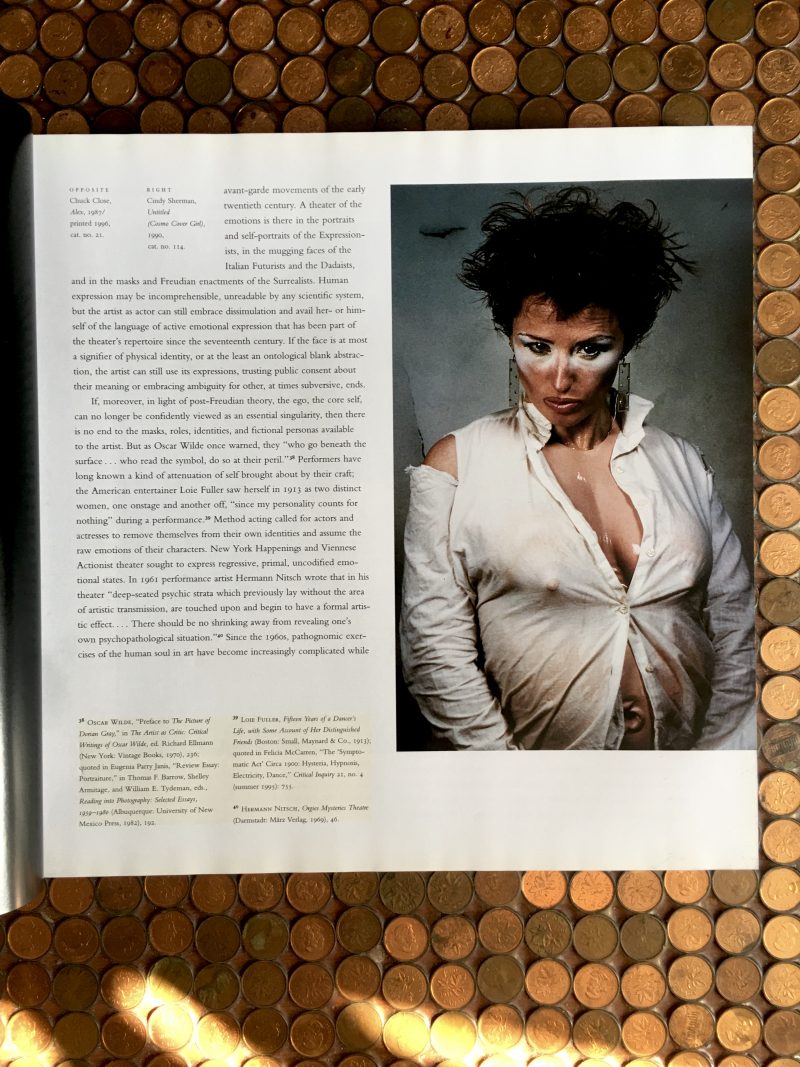

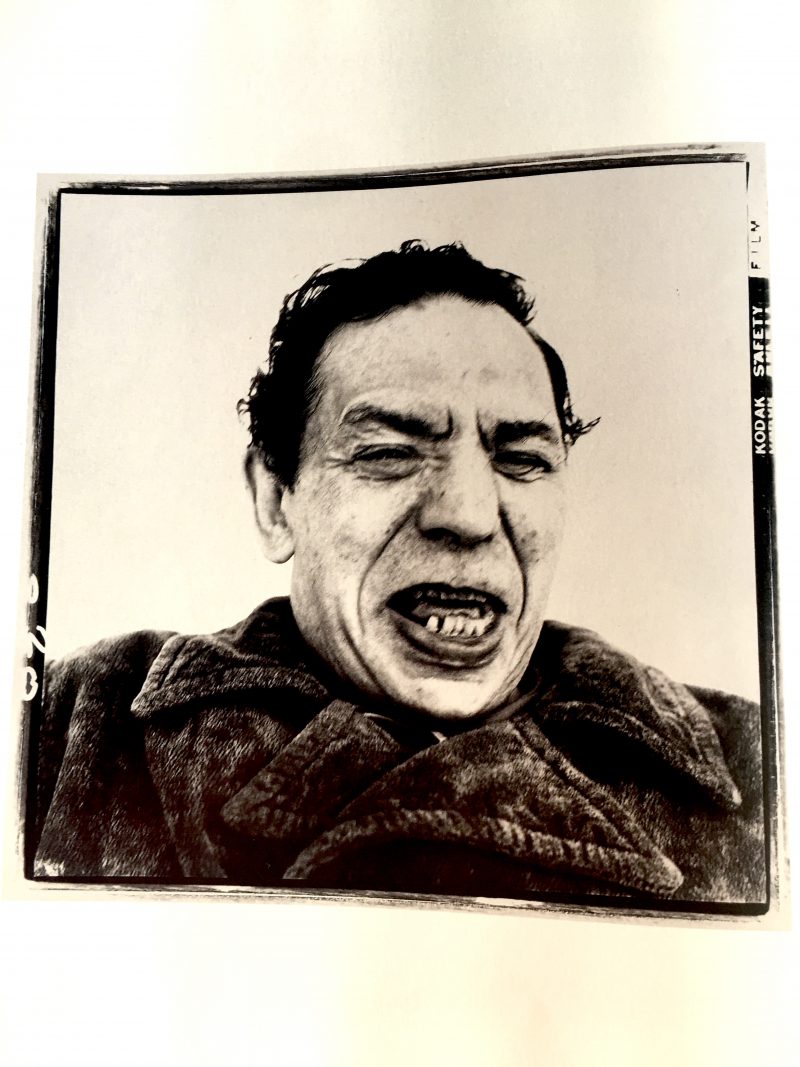

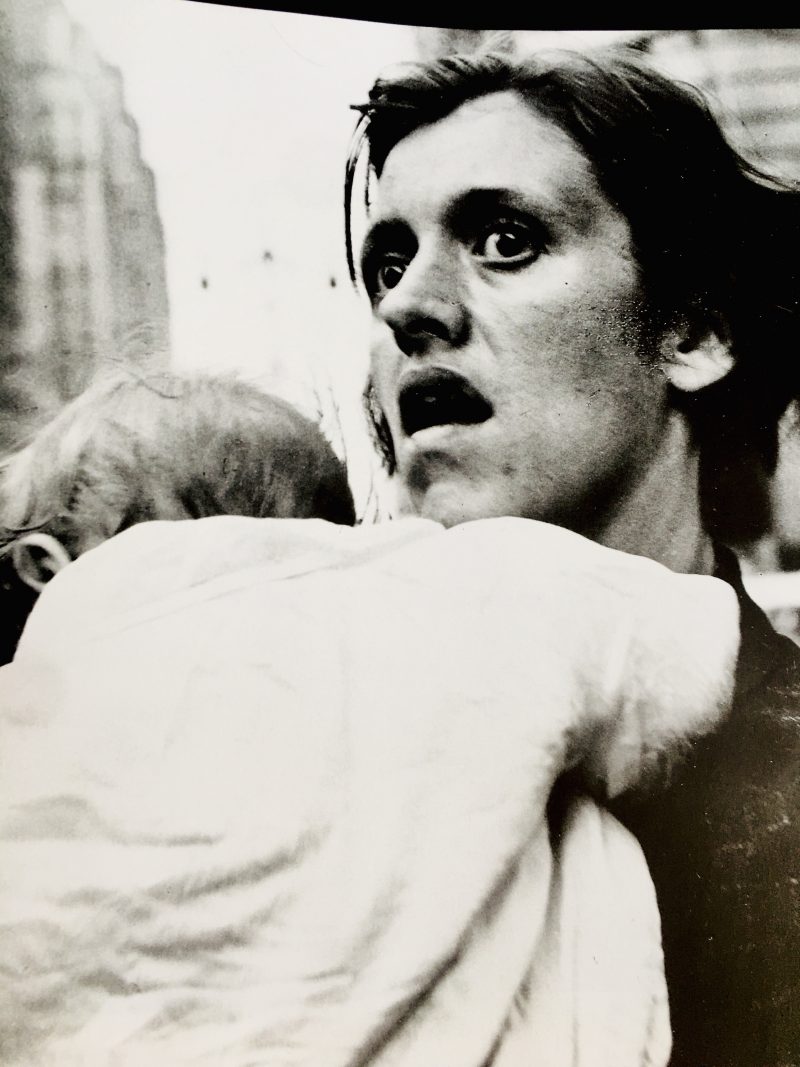

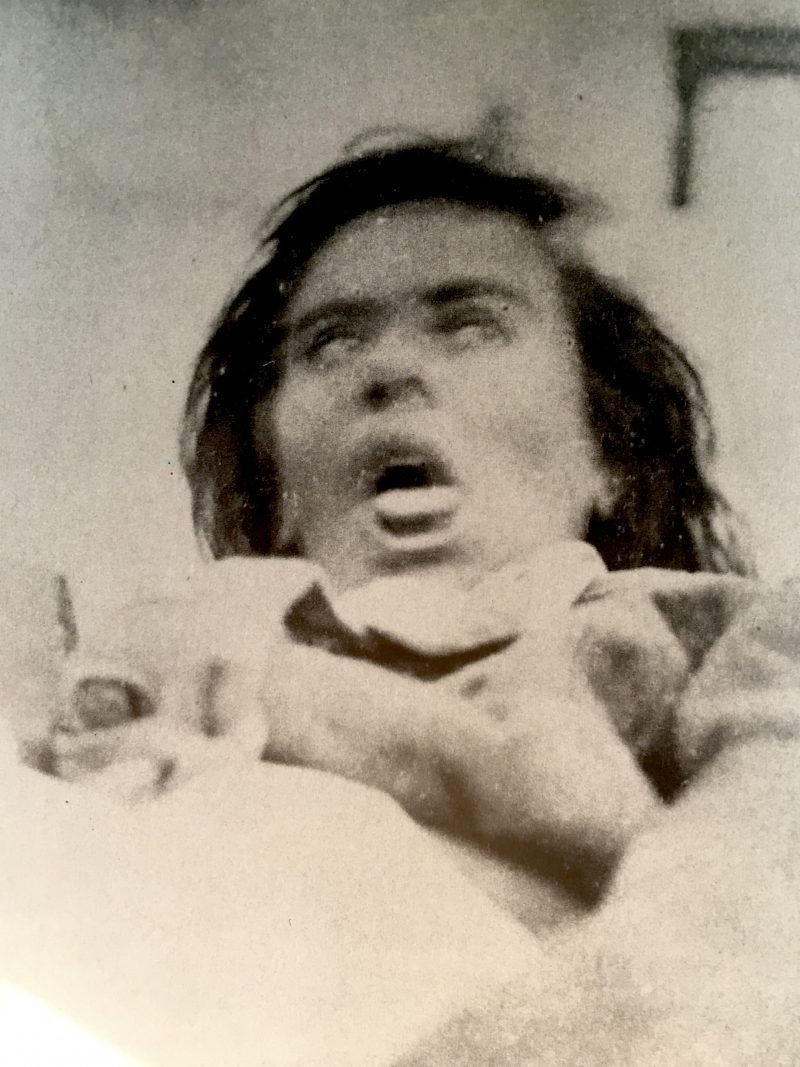

The post-Modern recoil from such neutralized concepts, at any rate, circles right back into Victorian ideas of pantomime, hyperventilation, and even the human being in extremis. Cindy Sherman’s film stills and Oscar Rejlander’s narrative portraits accentuate physiognomic expression with a vengeance. This world of creatures who pull a face would resemble those of Duchenne’s world, but for the sense that they’re manipulated by dramatic strategies, not prodded by electric instruments. It’s a staging of gestures, innocently anecdotal in Rejlander; disingenuous, with alarmist overtones in Sherman (the keynote artist of Sobieszek’s last essay in the catalog).

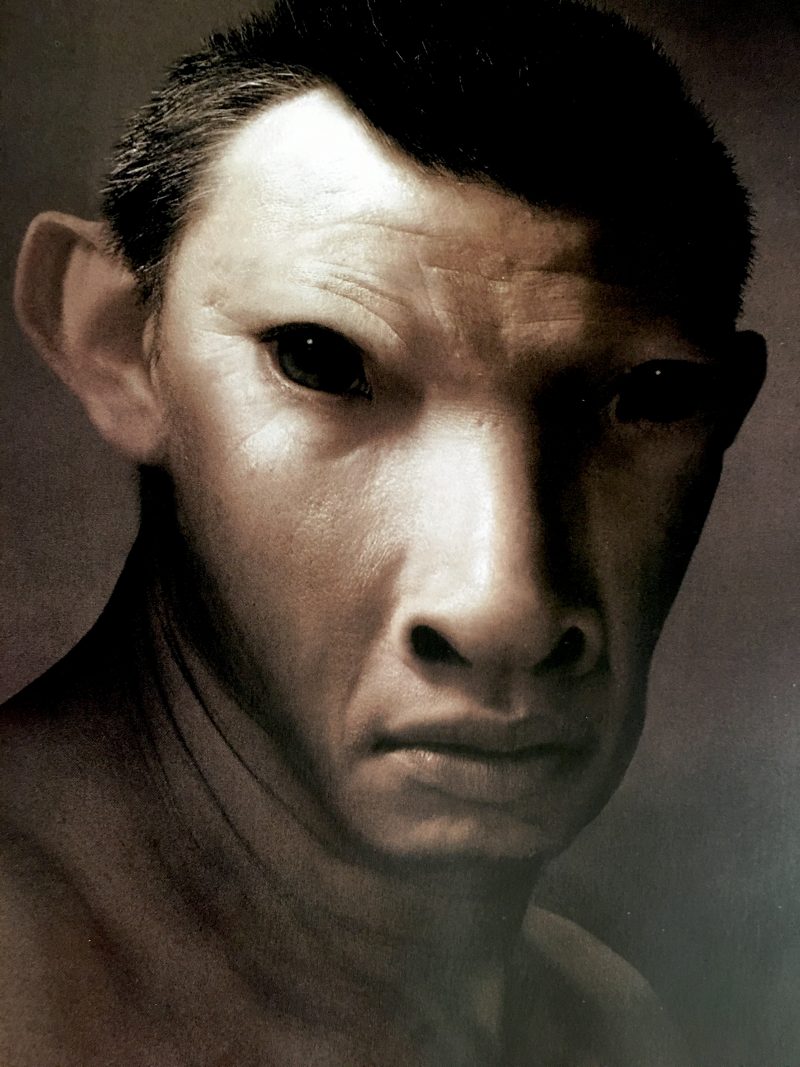

“The Ghost in the Shell” hits its stride in discussing the etiology of post-Modern

manias and multiple personalities. A line runs from Dr. Charcot’s photos of hysterics through Bruce Nauman’s screaming clowns, who throw fits but have no passion. Where once Modernists had emptied the face of keen and singular response, now it appears to swoon with a capricious rapture or look bewitched, as if possessed by foreign bodies. Sometimes, too, the visage is savagely treated: it’s missing a nose or mouth, as in the computer-manipulated work of Aziz + Cucher.

What might the presence of all these unhinged, somnambulistic, or disfigured characters signify? Well, obviously, the portentous question asked by such images is not who’s there, at that moment, but what is the enduring human condi-

tion, as conceived in our time? The cultures reflected by such work are technical cultures, above all involved with the study and control of bodily impulse, or prosthetic extensions of it. Faces tend therefore to act as vehicles for symbolic statement, reinforced by a dreamy and suffocating atmosphere.

Fascinating and, of course, dismal in equal measure, this symbolism needs to pump individuality right out of the creatures it visualizes. The torrent of affect in post-Modernist depictions of the face does imply a criticism of withdrawn demeanor in Modernist portraiture.

Still, even though the one style is highly fictive and the other clinically factual, both are fixated by personal displacement. This is a serious theme, well handled in film and literature, but shallowly treated in photography. Douglas Gordon Scotchtapes his face with grotesque result, but he merely updates Duchenne; Cindy Sherman’s disjointed dolls radiate terror, but do not achieve pathos. Either we have an indefinite and chaotic array of physical signs, or a gallery of denatured “meanings,” looking for a sign. I won’t argue against such an artistic vision of de-individuated humanity as a metaphor for suffering in our times; I say only that the spectacle of it is quite a bummer.

There’s something perverse about a humanist treatise such as this, which accentuates the scientist Duchenne but neglects Nadar and slights Lewis Hiñe. The sociality of those portraitists is indivisible from the aesthetic—and complex—pleasure we take from their imagery. But the catalog avoids any talk of social pleasures; it leaves us to conclude that in portrait tradition only the anesthetic tendency matters, all others being of concern only insofar as they might be inveigled into its various currents. Duchenne anesthetized his subject, a literal treatment that became metaphorical as time went on.

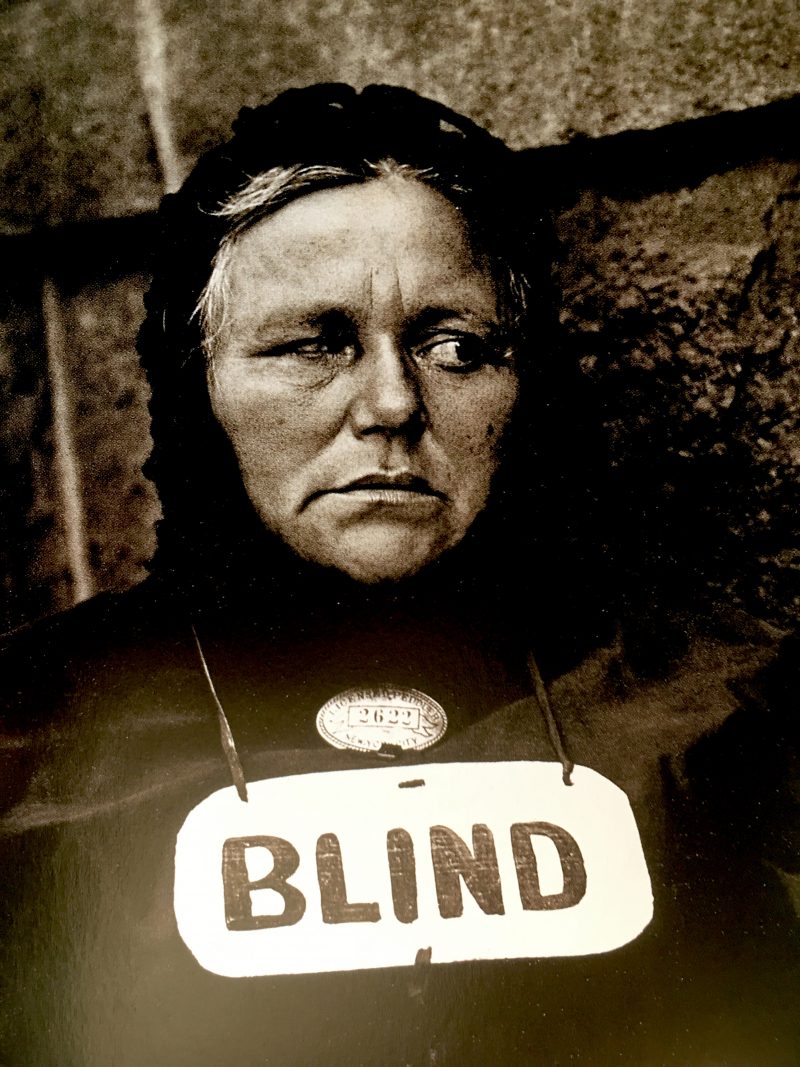

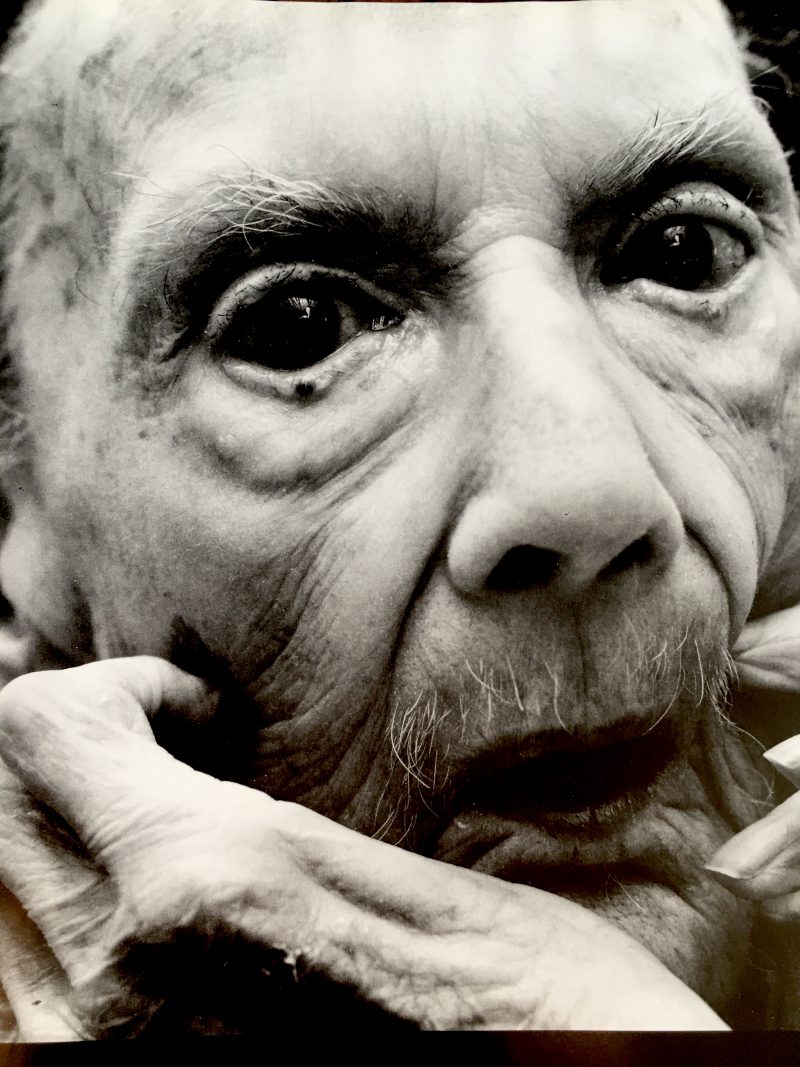

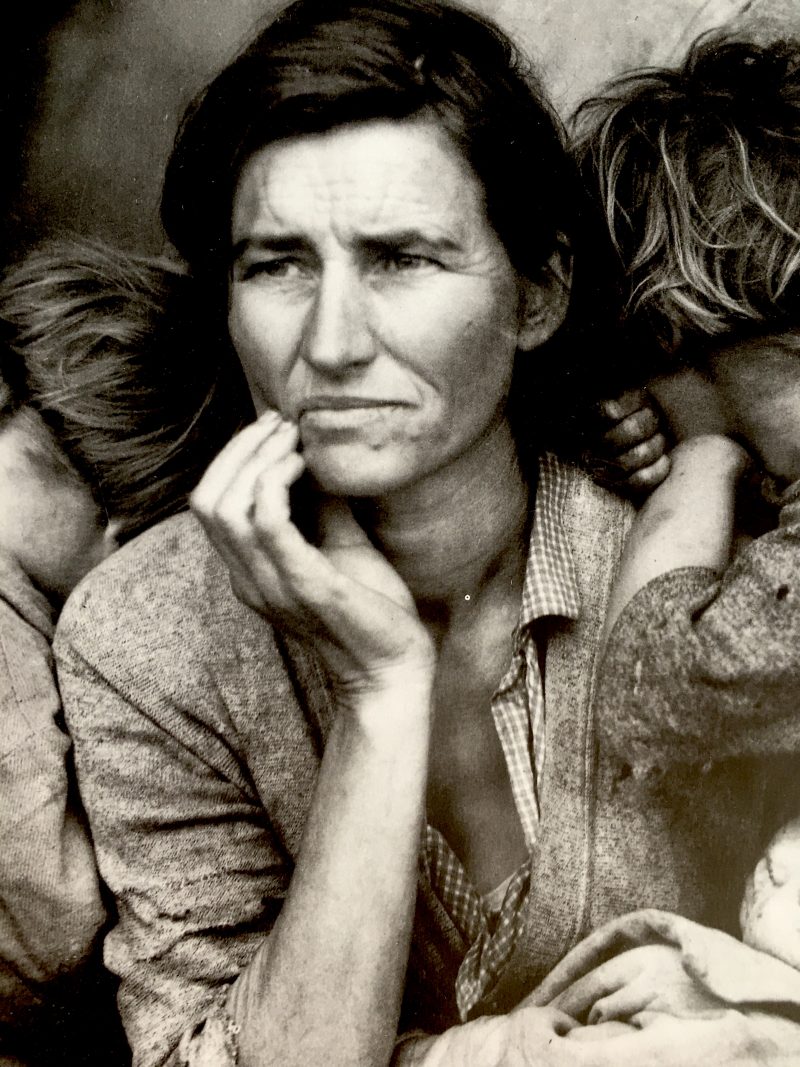

Anesthesia is a pain-relieving measure that dopes and devitalizes the human organism. When artists inject an anesthetic style into that marvelous pliancy we know as the human face, it’s as if to avoid an intolerable condition. But no one imagines this faintness of heart to be a caring attitude. On the contrary, the anesthetic style is so involved with implying debility that it can’t be bothered to move us, or really, even to disturb us. For that experience, please consider the woman in Paul Strand’s Blind, whose bearing is so vulnerable, yet powerful, and yes, monstrous, that the contradictions of her presence could only have been the discovery of an inquisitive mind. As in the best portraits, so in this one, the stimulus arises out of a generosity extended toward others, even if it must recognize their pain.

Blind is such a vital and charged image that we don’t at first perceive its

lonely atmosphere. In that so many post-Modernlst faces are not exactly personable, they sometimes have this quality of loneliness, too. Something has gone wrong with their genetics; artificial or alien devices have taken over their bodies, cloning or metamorphoses of the uncanny sort that trace back to Ovid, now brought up to date by computer science and media. These pariahs live, if that’s not too strong a word, in an unsharable space. Frankenstein’s monster was imprisoned in that space and raged against it. When he emerges from anesthesia (death), he terrifies us by the vengeance he takes upon a society that cannot accept his difference.

By contrast, we perceive loneliness in portraiture as a state with which we can empathize. For it signifies that very recognizable and human condition of being among our fellows, but not with them. How often the feeling of it comes to us in a face shaded with regret or introspection. You can see it in Roy DeCarava’s Billie Holliday, as well as in the melancholy of Alfred Stieglitz’s portraits. Albert S. Southworth’s daguerreotypes have it, too. There’s something tender about the light in these umbrageous pictures, a hovering or modulated tone in which the characterization subsides. Yet, when we engage with these sitters, our tentative distance from them seems reduced, as if their self-reflectiveness had been drawn out to merge with our own.

Far from being marginal, this perception is common in the experience of portraiture. Without doubt, the characterization of loneliness is an artifice, contrived in different ratios by both the sitter and the portraitist. At the same time, the appeal of loneliness plays upon a social sentiment, a viewer’s solidarity with those who, higher or lower in worldly station, compose themselves before the lens for largely unknown and absent publics. An artist’s vision is possibly at stake on these occasions, but so is the subject’s dignity. And as the suspense of their encounter manifests itself, the open sense of the picture radiating with subtle possibilities, the sitters become part of our thought.

Max Kozloff