History of Crime: The Project

PROJECT ON HOLD.

“Grave as the fact is, one might laugh

Almost to see the photograph

So ignominiously applied

To serve as the Policeman’s guide.”

– Cuthbert Bede, published in Punch in 1853.

Almost fifty years has passed since the police busted the Isaacs Gallery in Toronto for – according to a CBC radio report – “exhibiting a disgusting object.” Mark Prent was barely out of school at the time of this incident, but it cemented his reputation as a creator of extreme sculptures. Within fifteen years, he’d have a survey exhibition alongside David Cronenberg at the newly opened Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery. In the thirty years since then, he’s maintained a lower profile but continues to make work that merits a similarly visceral response. That gut feeling, which is not surprisingly elicited by depictions of guts and grotesque renderings of the body, has also fallen out of fashion in the art world. It’s present in horror movies and makes its way into galleries through boundary-crossing curation like the Art Gallery of Ontario’s recent Guillermo del Toro exhibition, but the secret history of exhibiting disgusting objects locally only recently broke the surface for the first time in a while with the unshuttering of John Vincent’s collection at his ENEMY PREY IGNORE museum gallery in the city’s west end.

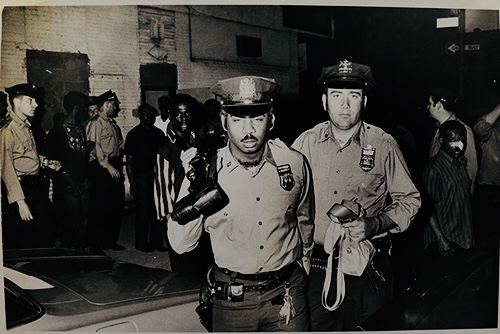

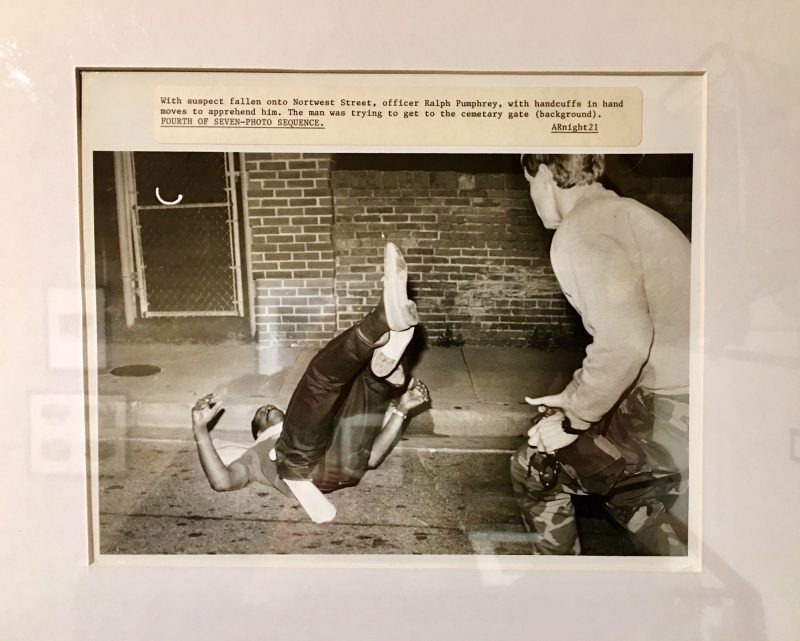

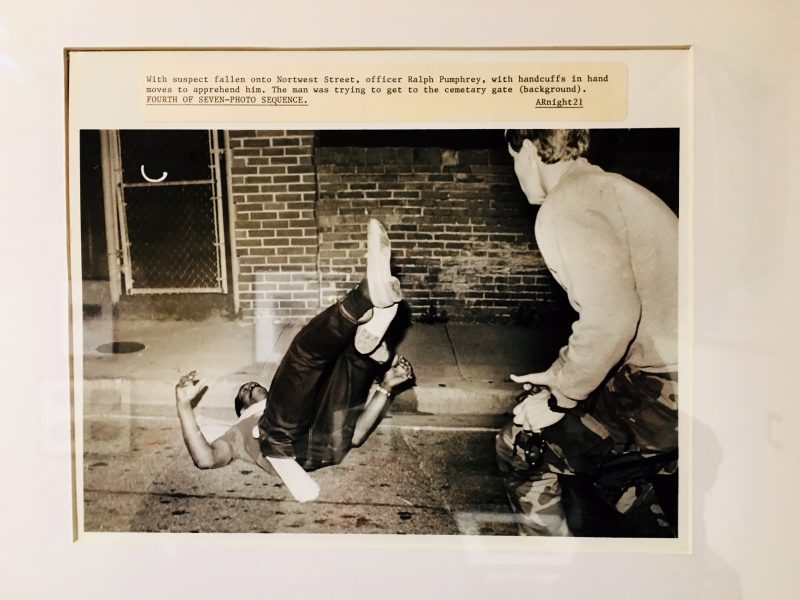

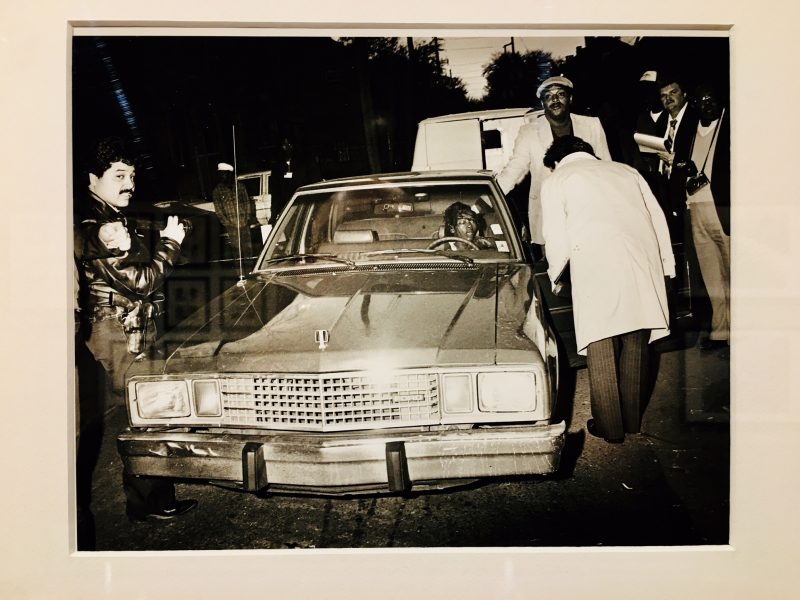

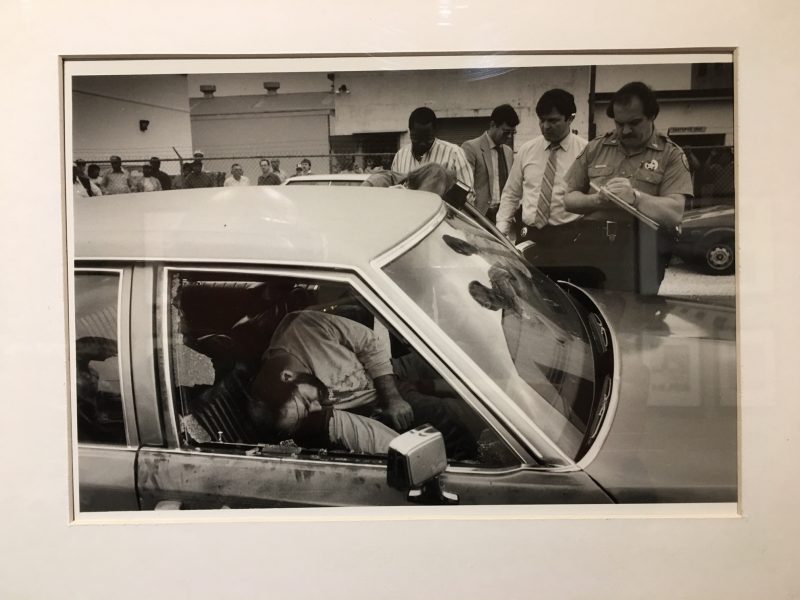

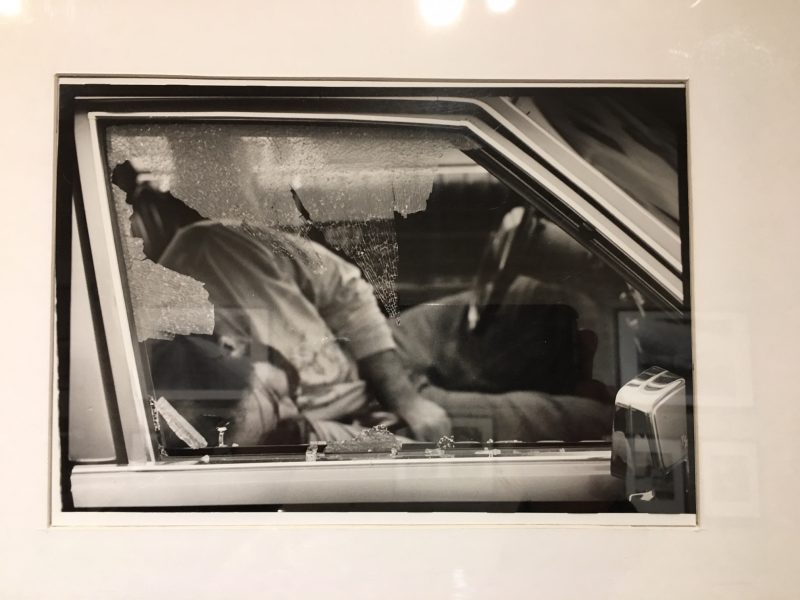

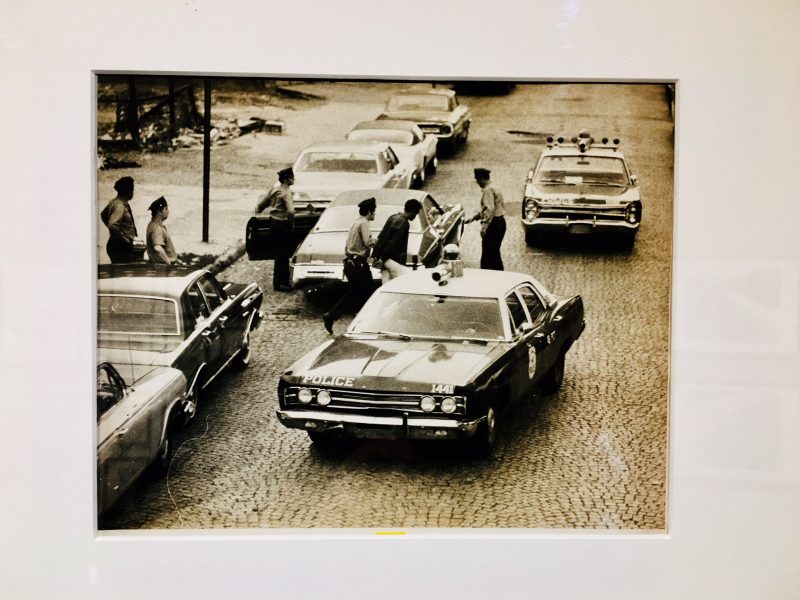

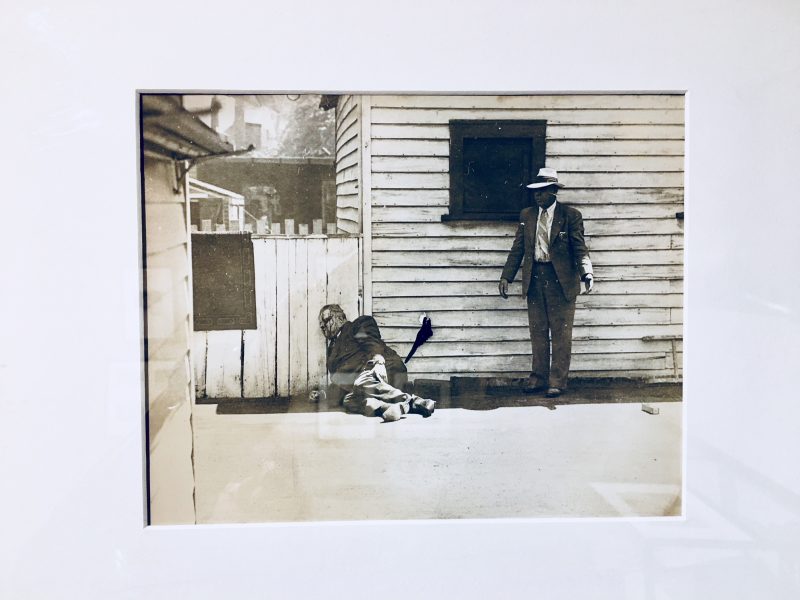

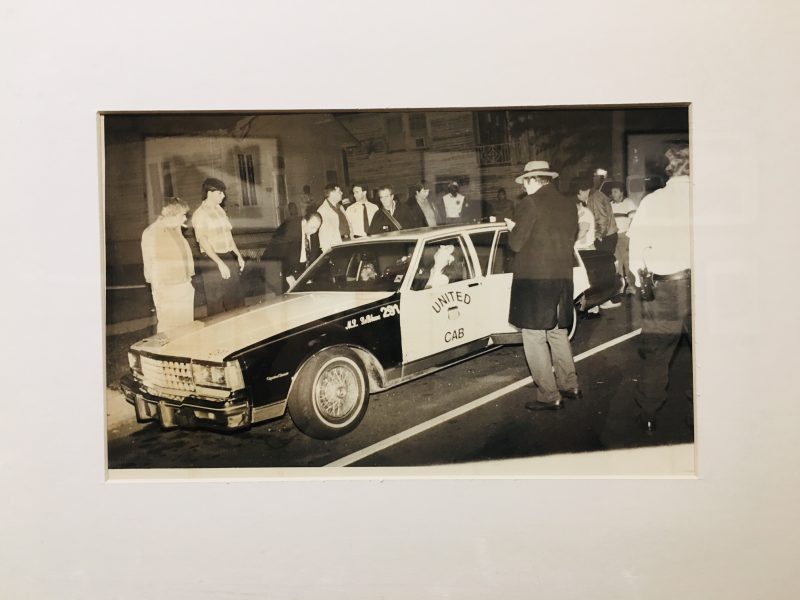

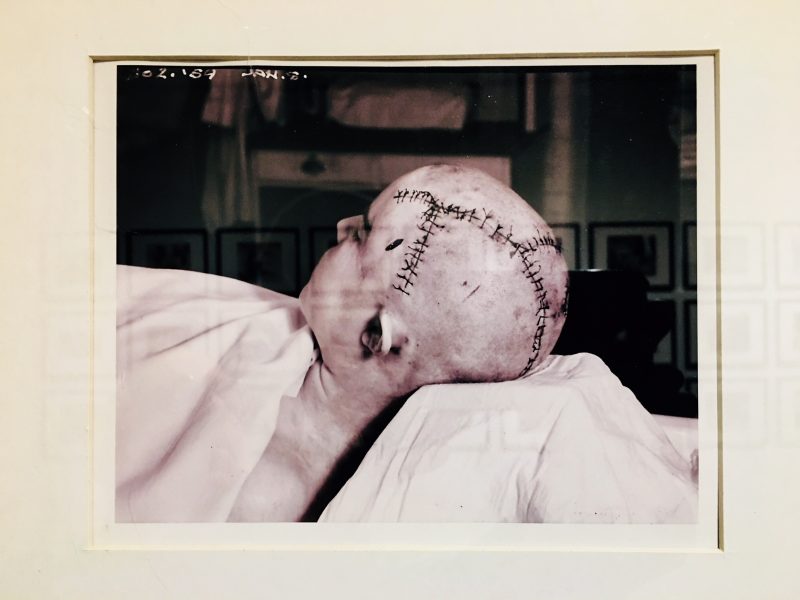

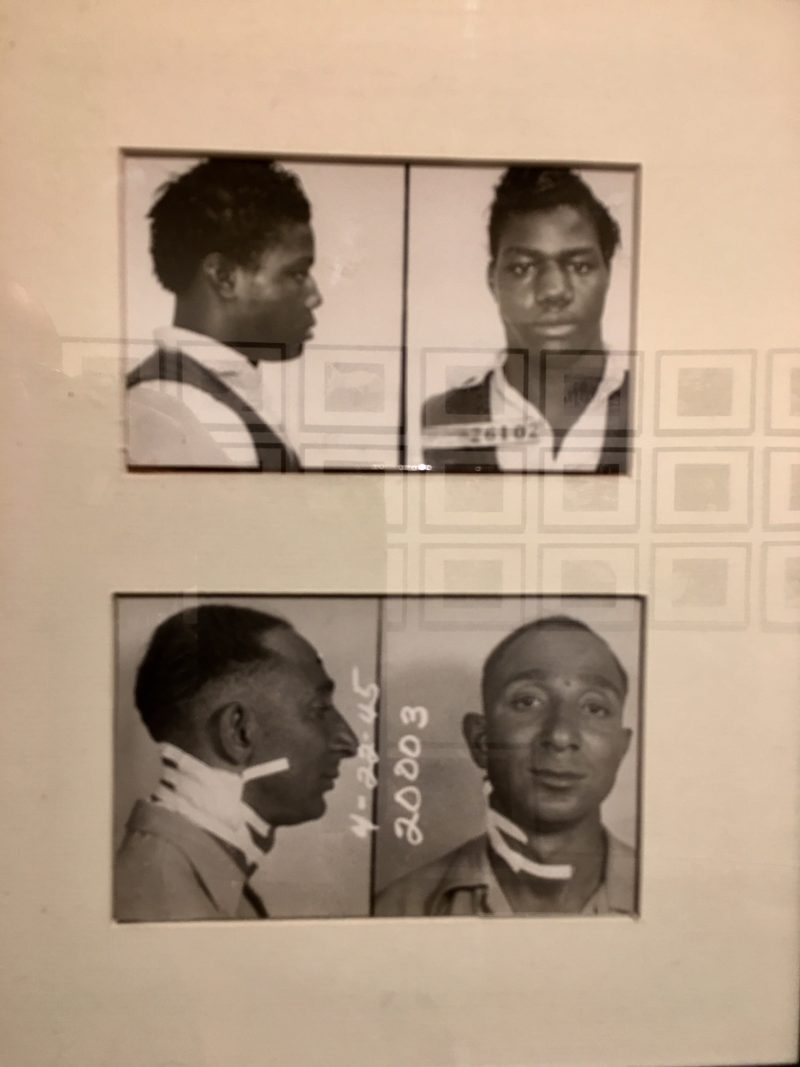

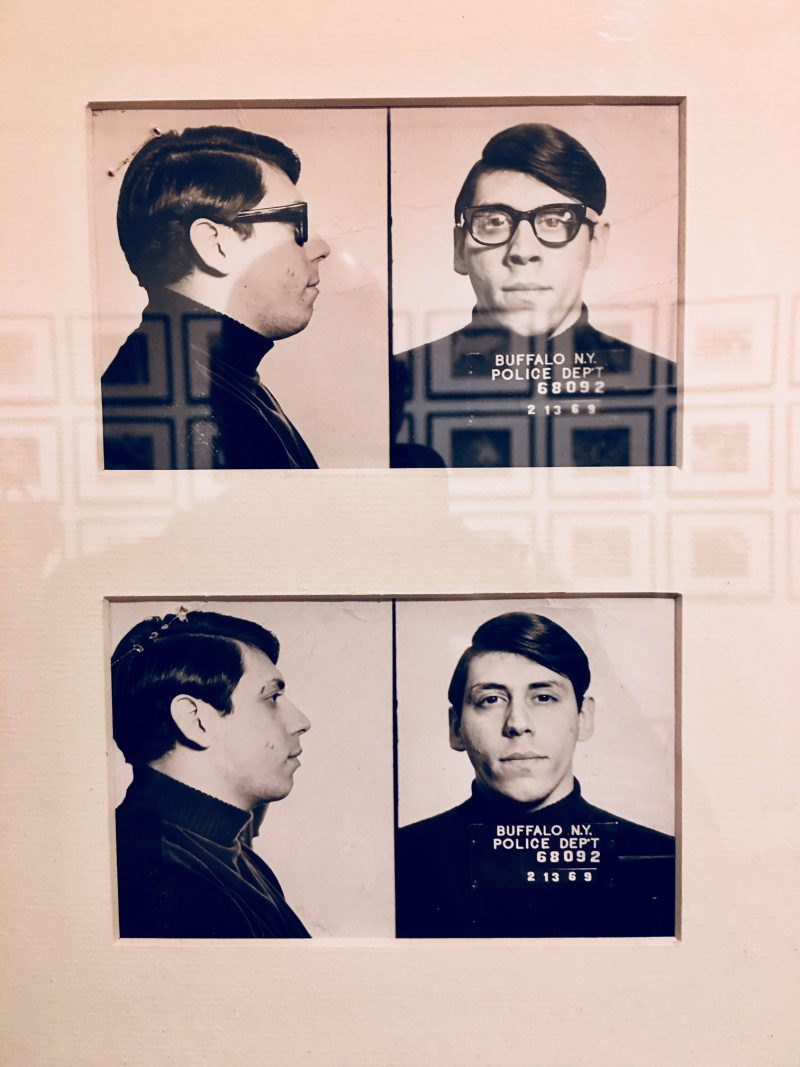

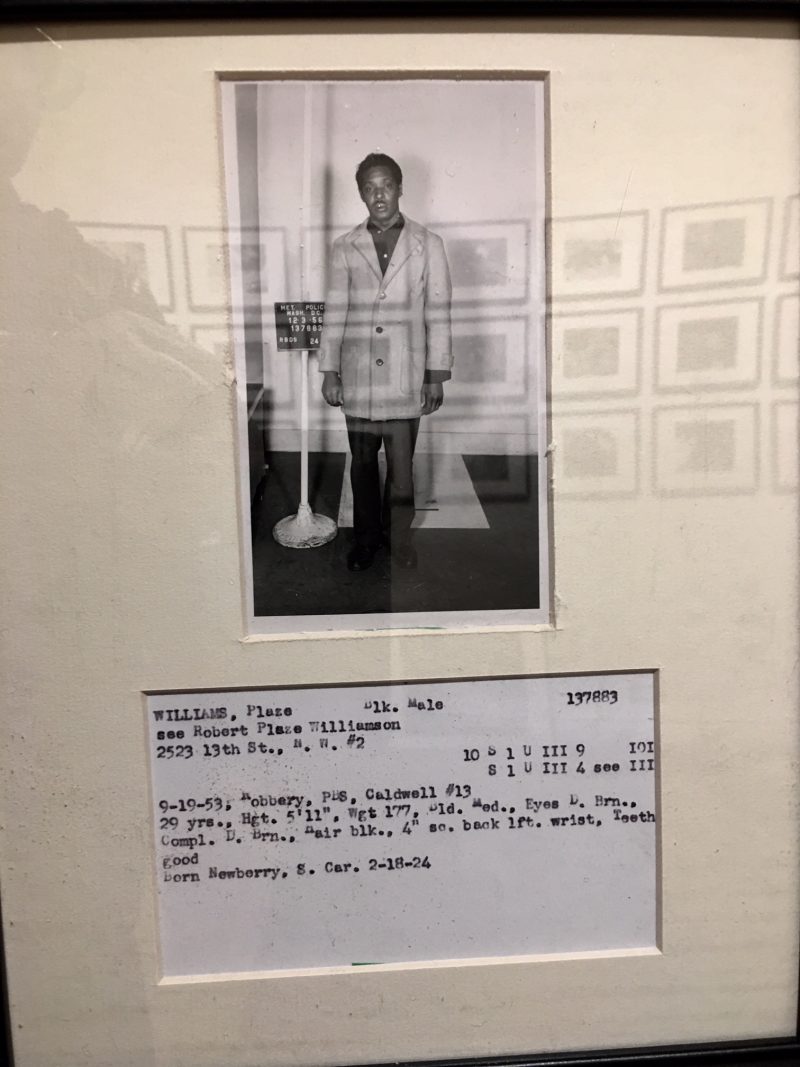

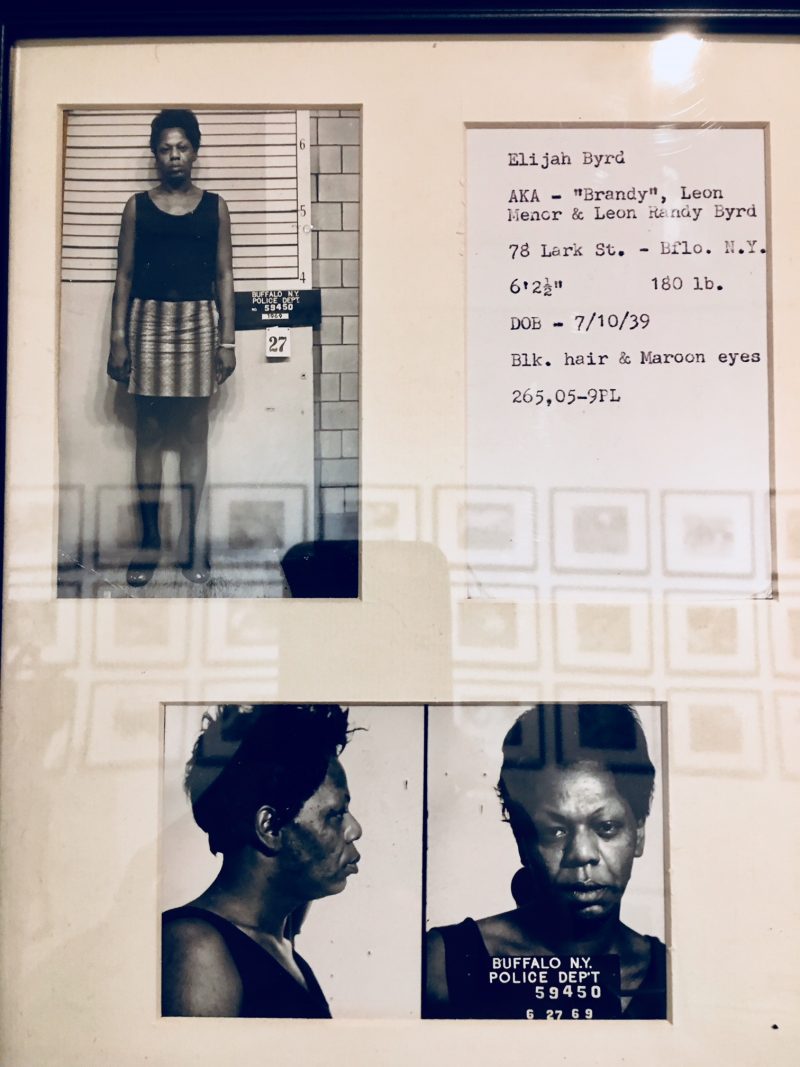

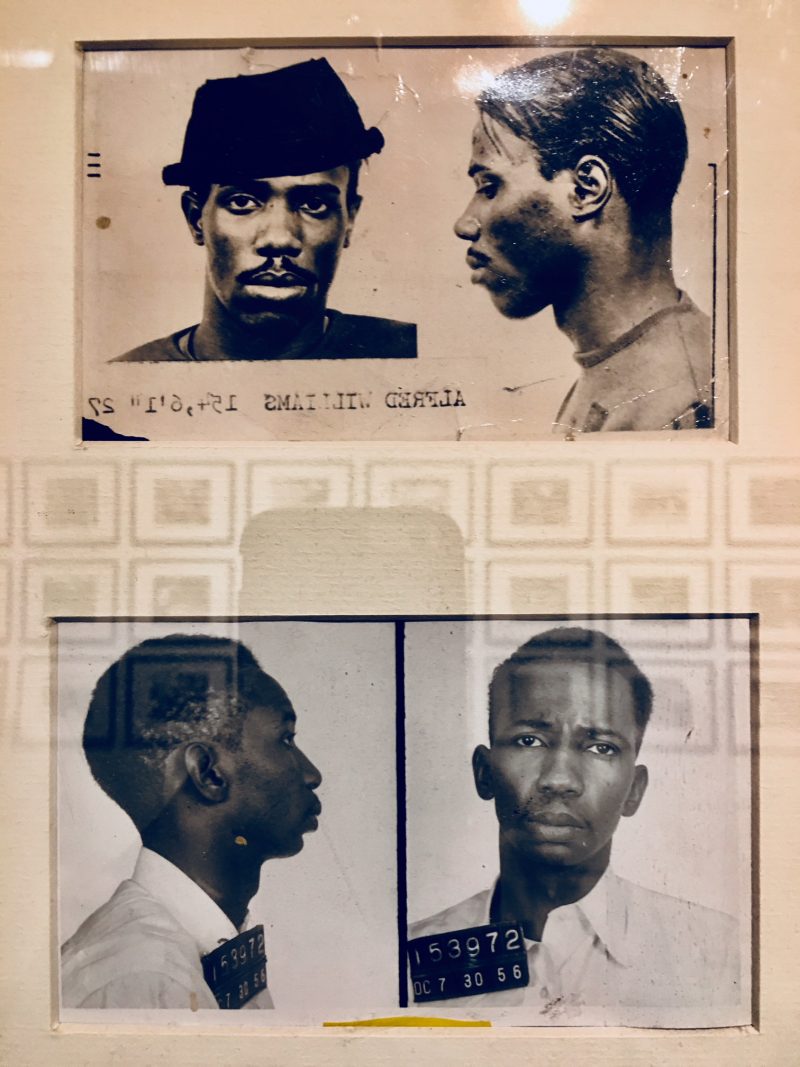

A brief conversation with the artist who now finds himself a gallerist and a tour of his workshop is all that’s needed to draw a line from Prent (whose work Vincent owns) through Toronto-based special effects specialist Gordon Smith to the contemporary artist Evan Penny (whose hyperrealistic figures owe something of a debt to his time making bodies for the movies) to the late Bill Jamieson (who almost had an exhibition at The Power Plant of his collection of oddities and curiosities). Before you get to the backroom of body art and artefacts, the main attraction at this low key venue (advertising consists of posters, postcards, and a nascent Instagram page) is a display of crime scene photographs that range from the intriguingly mundane to what I’d consider relatively graphic were it not for Vincent’s comments about the pictures he didn’t include.

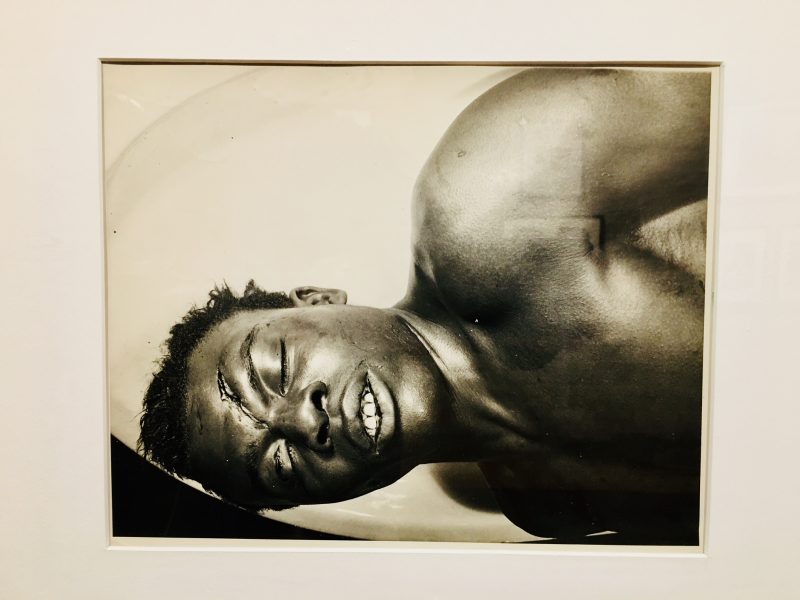

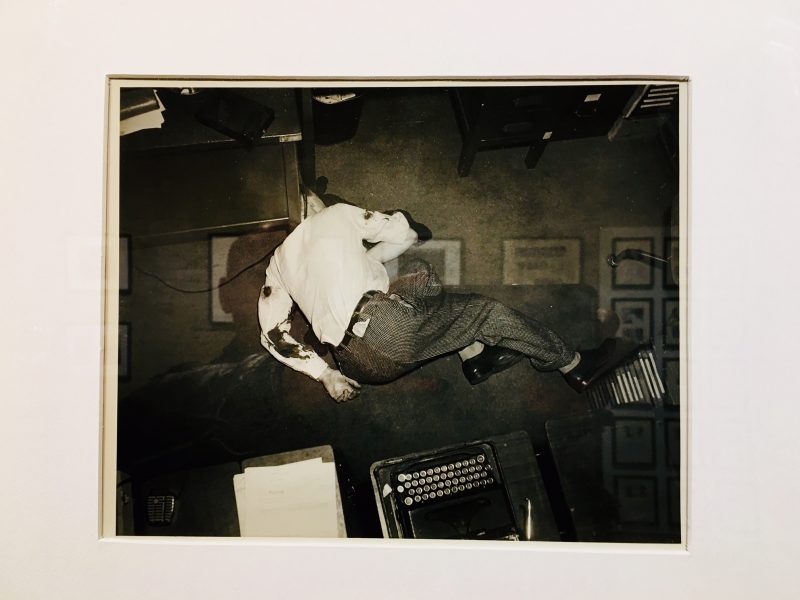

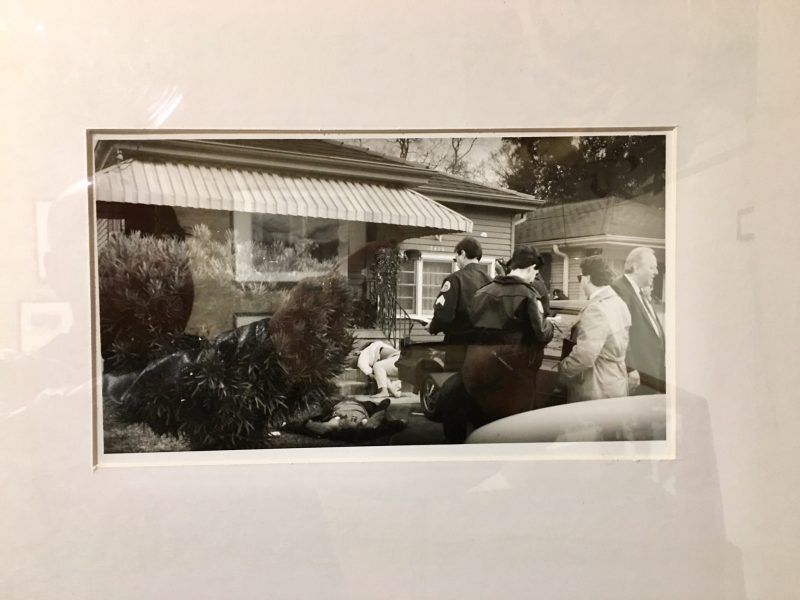

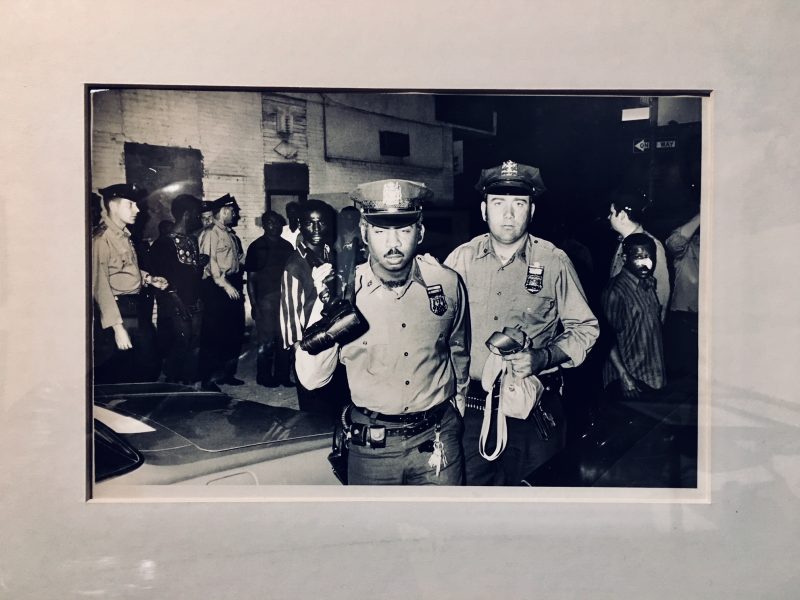

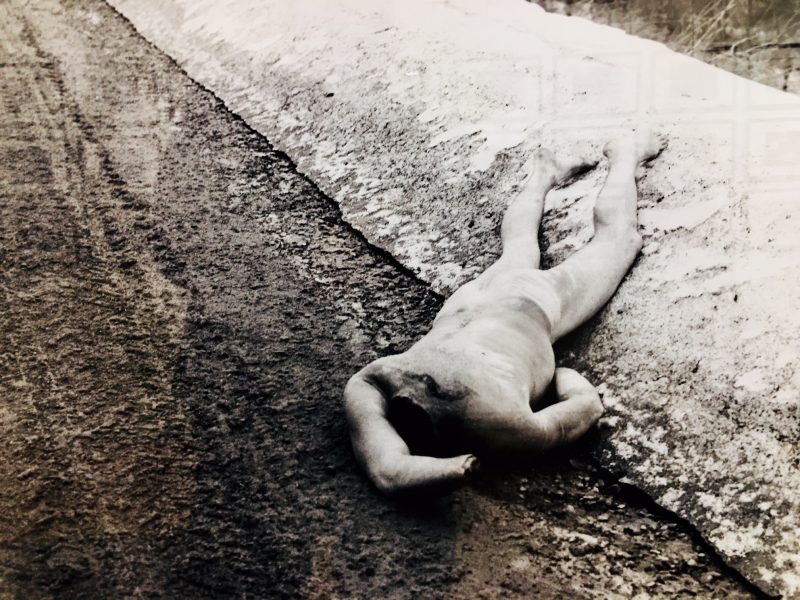

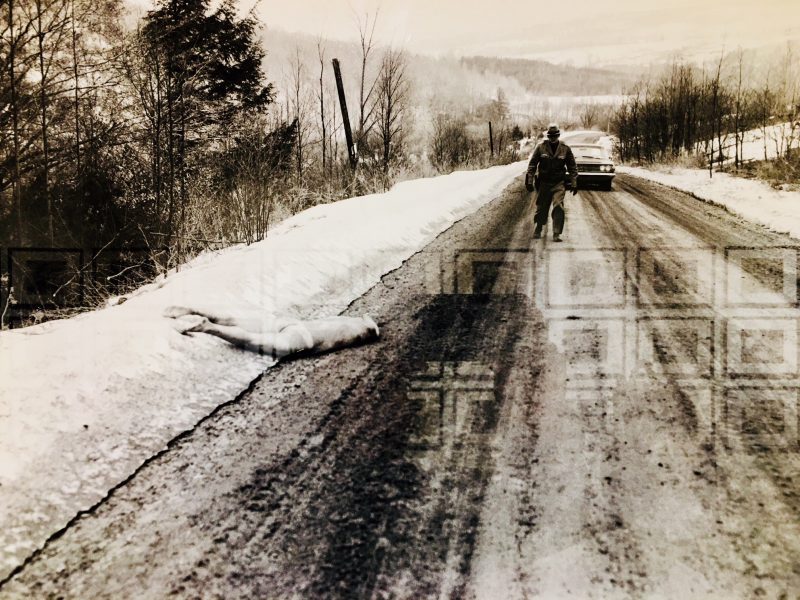

There is a risk in showing this type of material simply for the sake of shock value. Thomas Hirschhorn’s installation at The Power Plant in 2011 included far more disturbing imagery of the effects of violence. He tried to have it both ways by criticizing our attraction to abhorrent pictures while also reducing them to elements in a larger and highly theorized artwork. None of those games are evident at EPI where the appreciation of the photographs from various points in the 20th Century is inescapably bound to our familiarity with the same scenes played out in police procedural crime dramas and Hollywood/Netflix/HBO thrillers (Vincent pointed out that the set designers from those productions likely looked through these kinds of archival shots to get their desired look). However, even before those stylistic references, there’s a forensic aesthetic evident in the framing and lighting of every damaged body and a sliver of narrative captured in the theatrical poses of the nameless cops and bystanders who find themselves in these devastating, yet everyday circumstances.

Once the initial Wow!/Ick! reaction has passed, there remains the documentary fact that these horrible events happened to real people. Critical distance isn’t possible when fellow creatures are at stake, and so there arises an unexpected tenderness in even the most harrowing pictures. A naked, headless, and handless body, probably the victim of a mob killing, left as a message on the side of a barren road in the middle of winter, the kind of corpse that piles up in action flicks and gangster stories, becomes unspeakably tragic when framed in black and white. Apart from the violence that preceded the pictures being taken, there is little that is disgusting about this collection and much to feel. That gut reaction, the one that keeps us from getting too close to the precipice, the one we tease by watching recreations of unthinkable acts on television, the one that reminds us how fragile we are and how easy it is to die, that feeling isn’t one of revulsion but of fear. It controls us and fascinates us and routinely saves our lives. Perhaps it’s because we get it from other sources that we don’t need to find it in our galleries. But it’s been there before (well before 1972) and, like they say in the movies, IT’S BACK!

A History of Violence: Crime Scene Photography

ENEMY PREY IGNORE museum gallery:

The gallery is located at 2057 Dundas Street West

Terence Dick is a freelance writer living in Toronto. His art criticism has appeared in Canadian Art, BorderCrossings, Prefix Photo, Camera Austria, Fuse, Mix, C Magazine, Azure, and The Globe and Mail. He is the editor of Akimblog.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

http://www.akimbo.ca/akimblog/index.php?id=1368

https://www.wired.com/2015/12/burden-of-proof-exhibition-crime-photography/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_forensic_photography

http://www.forensicsciencesimplified.org/photo/