Vivian Maier Photographs & Project

PROJECT CANCELLED due that darn pandemic. xx

VIVIAN MAIER Photography Exhibition

Curated by Guy Berube, director, LPM Projects

A riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma.

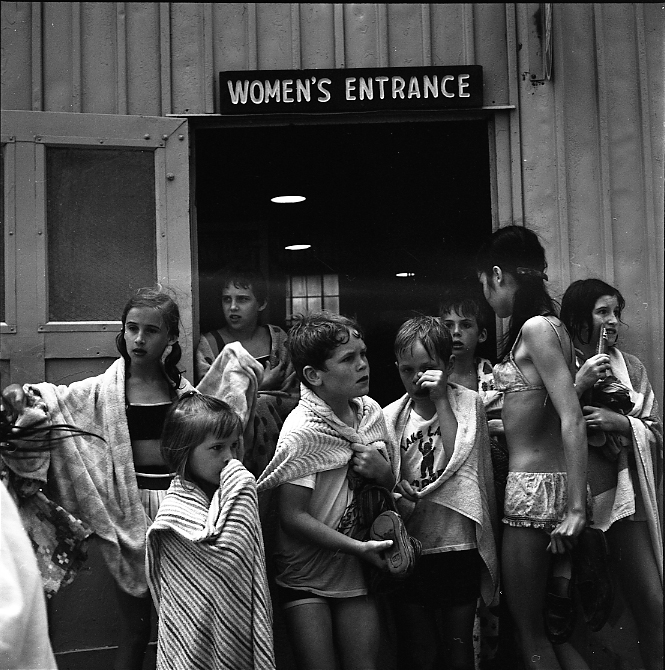

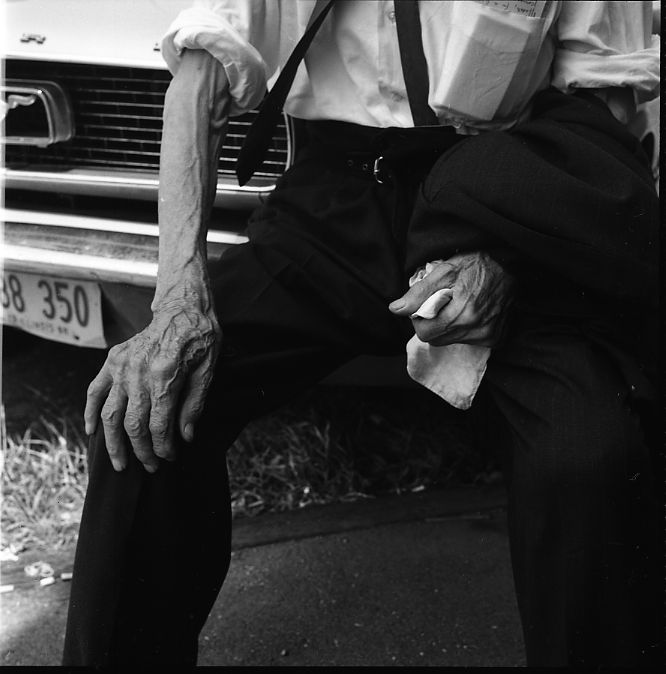

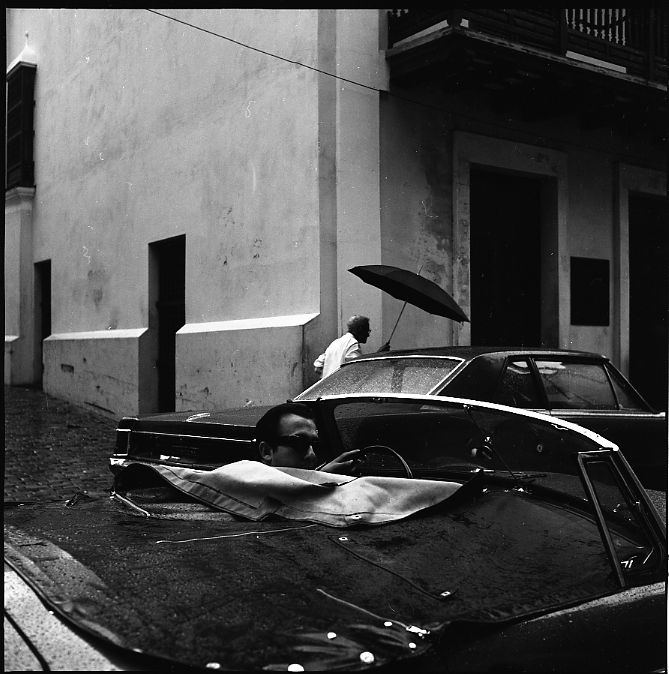

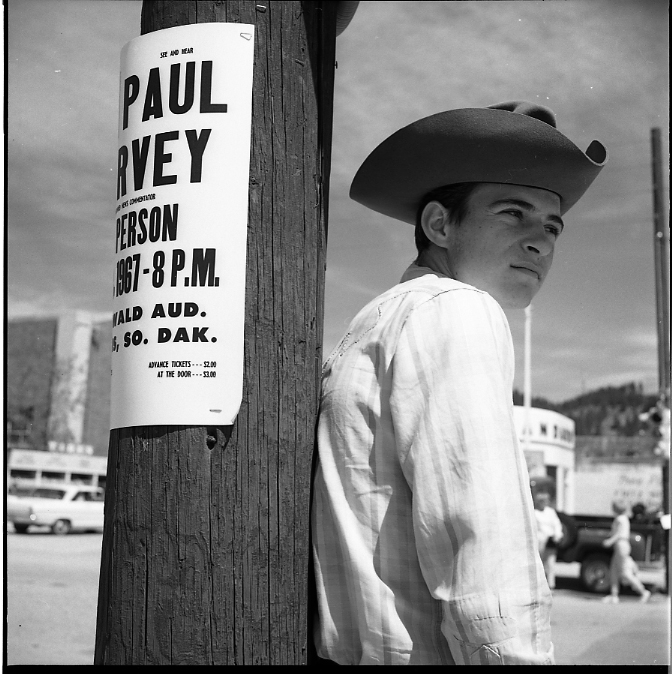

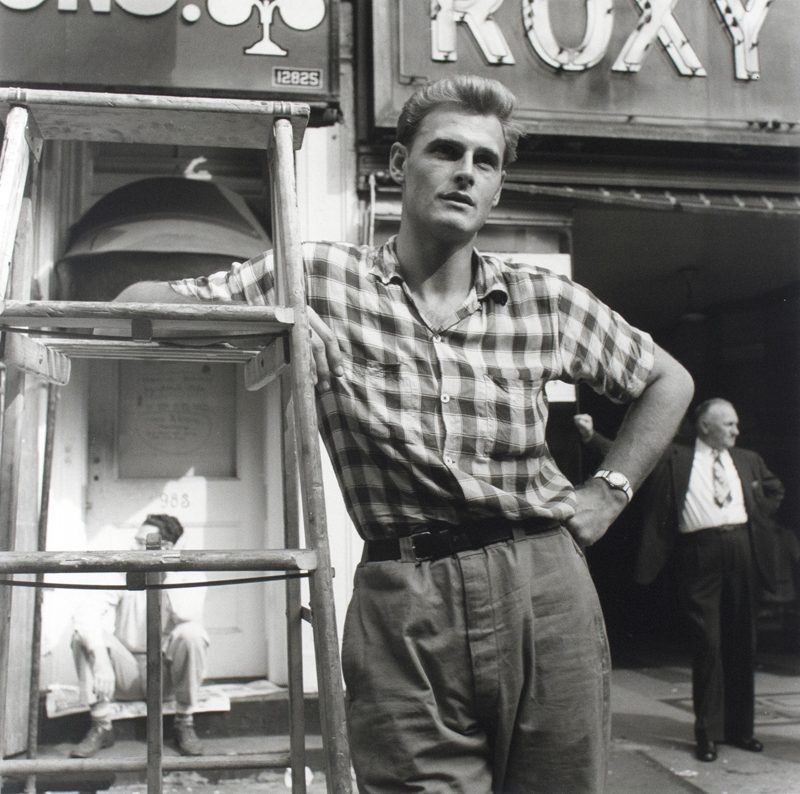

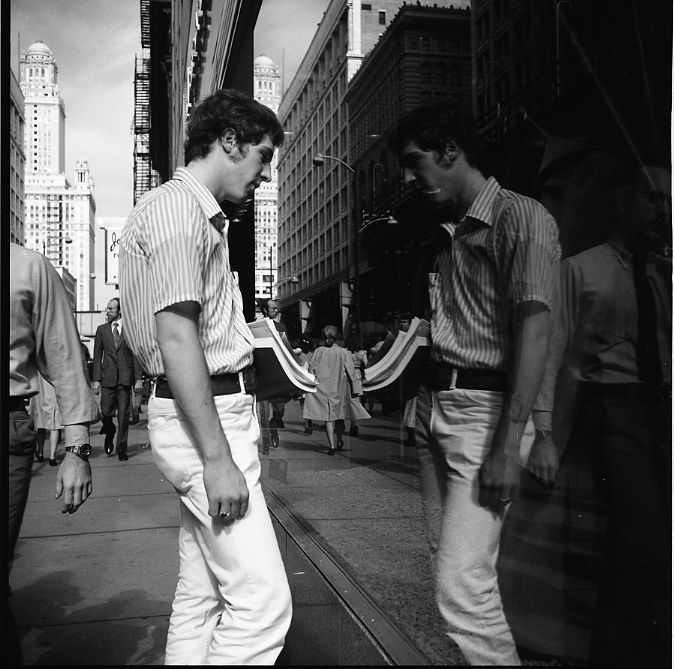

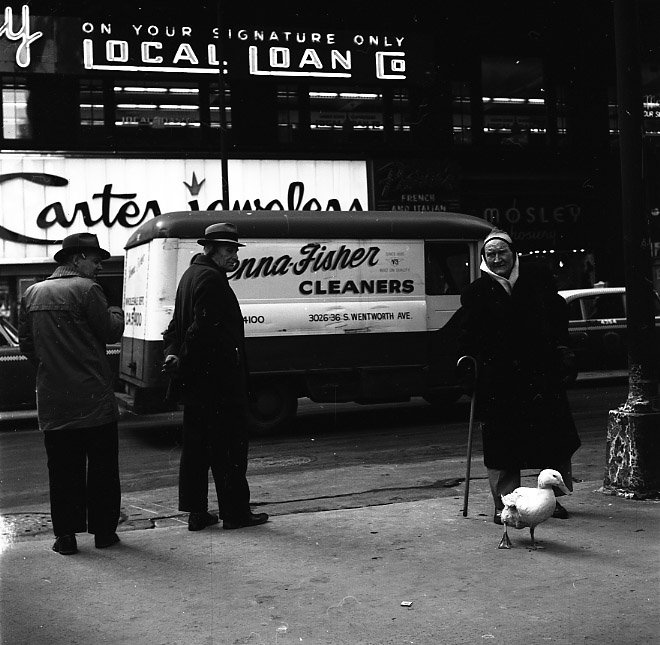

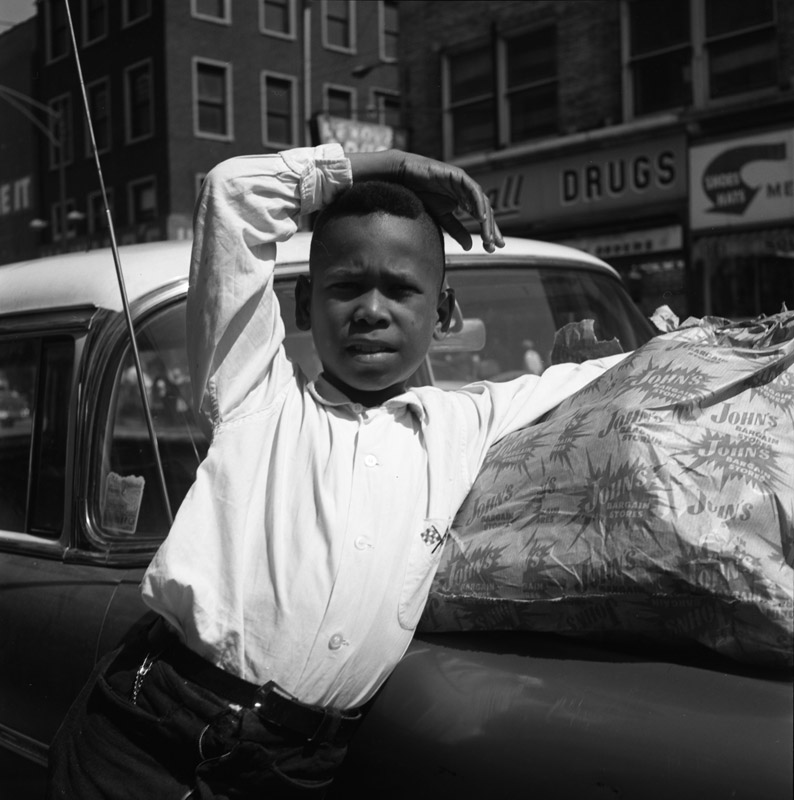

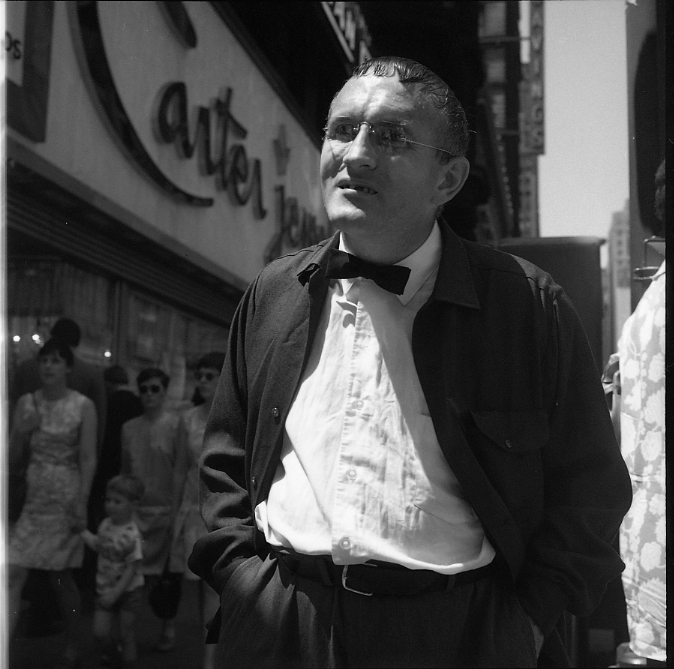

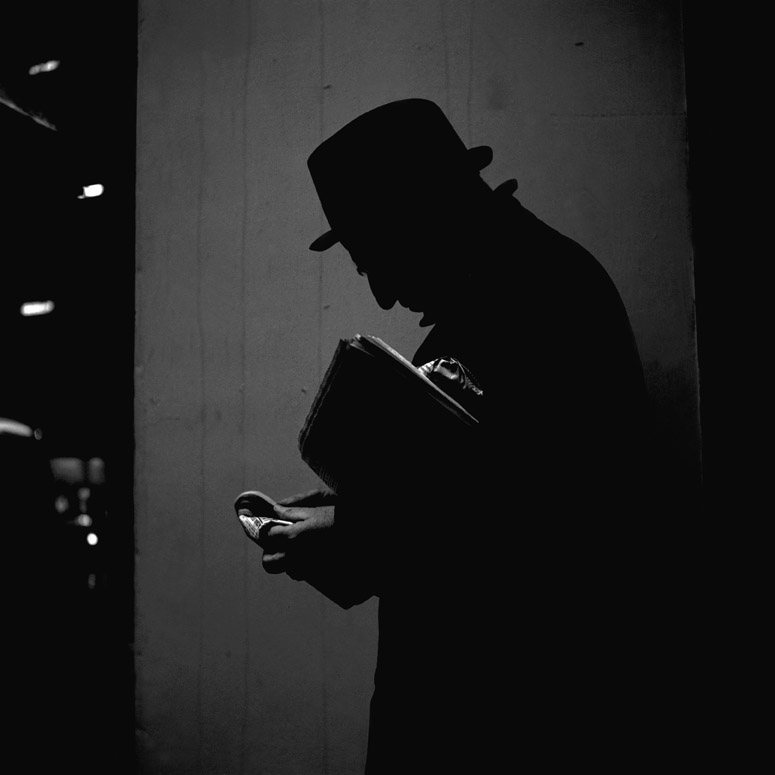

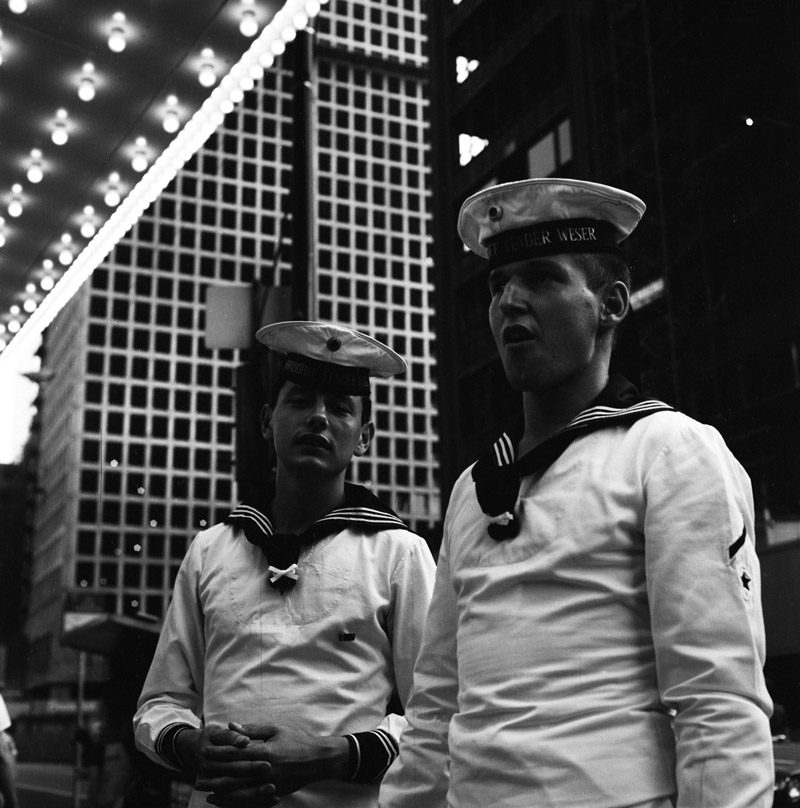

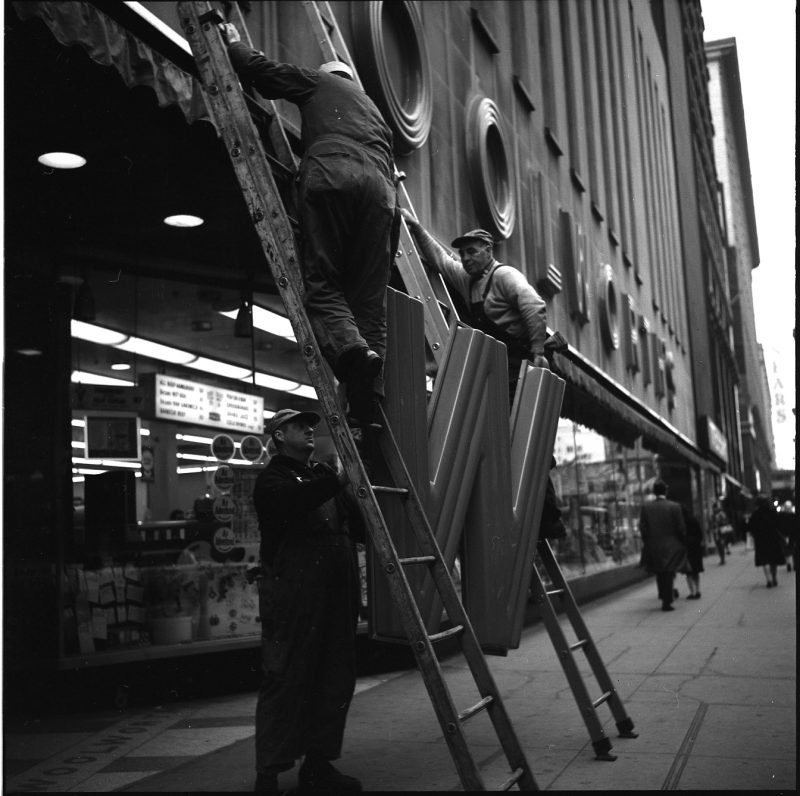

Piecing together Vivian Maier’s life can easily evoke Churchill’s famous quote about the vast land of Tsars and commissars that lay to the east. A person who fit the stereotypical European sensibilities of an independent liberated woman, accent and all, yet born in New York City. Someone who was intensely guarded and private, Vivian could be counted on to feistily preach her own very liberal worldview to anyone who cared to listen, or didn’t. Decidedly unmaterialistic, Vivian would come to amass a group of storage lockers stuffed to the brim with found items, art books, newspaper clippings, home films, as well as political tchotchkes and knick-knacks. The story of this nanny who has now wowed the world with her photography, and who incidentally recorded some of the most interesting marvels and peculiarities of Urban America in the second half of the twentieth century is seemingly beyond belief.

An American of French and Austro-Hungarian extraction, Vivian bounced between Europe and the United States before coming back to New York City in 1951. Having picked up photography just two years earlier, she would comb the streets of the Big Apple refining her artistic craft. By 1956 Vivian left the East Coast for Chicago, where she’d spend most of the rest of her life working as a caregiver. In her leisure Vivian would shoot photos that she zealously hid from the eyes of others. Taking snapshots into the late 1990′s, Maier would leave behind a body of work comprising over 100,000 negatives. Additionally Vivian’s passion for documenting extended to a series of homemade documentary films and audio recordings.

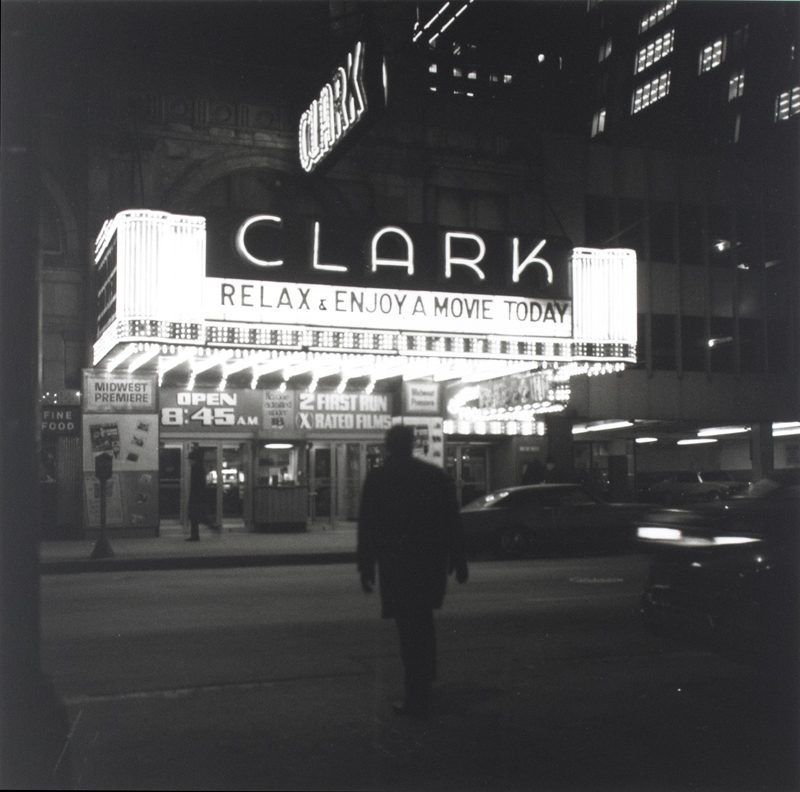

Interesting bits of Americana, the demolition of historic landmarks for new development, the unseen lives of various groups of people and the destitute, as well as some of Chicago’s most cherished sites were all meticulously catalogued by Vivian Maier.

A free spirit but also a proud soul, Vivian became poor and was ultimately saved by three of the children she had nannied earlier in her life. Fondly remembering Maier as a second mother, they pooled together to pay for an apartment and took the best of care for her. Unbeknownst to them, one of Vivian’s storage lockers was auctioned off due to delinquent payments. In those storage lockers lay the massive hoard of negatives Maier secretly stashed throughout her lifetime.

Maier’s massive body of work would come to light when in 2007 her work was discovered at a local thrift auction house on Chicago’s Northwest Side. From there, it would eventually impact the world over and change the life of the man who championed her work and brought it to the public eye, John Maloof.

Currently, Vivian Maier’s body of work is being archived and cataloged for the enjoyment of others and for future generations. John Maloof is at the core of this project after reconstructing most of the archive, having been previously dispersed to the various buyers attending that auction. Now, with roughly 90% of her archive reconstructed, Vivian’s work is part of a renaissance in interest in the art of Street Photography.

*

VIVIAN MAIER

“Well, I suppose nothing is meant to last forever. We have to make room for other people. It’s a wheel. You get on, you have to go to the end. And then somebody has the same opportunity to go to the end and so on.” – Vivian Maier

Vivian Maier (February 1, 1926 – April 21, 2009) was an American street photographer born in New York City. Although born in the U.S., it was in France that Maier spent most of her youth. Maier returned to the U.S. in 1951 where she took up work as a nanny and care-giver for the rest of her life. In her leisure however, Maier had begun to venture into the art of photography. Consistently taking photos over the course of five decades, she would ultimately leave over 100,000 negatives, most of them shot in Chicago and New York City. Vivian would further indulge in her passionate devotion to documenting the world around her through homemade films, recordings and collections, assembling one of the most fascinating windows into American life in the second half of the twentieth century.

*

EARLY YEARS

Maier was born to a French mother and Austrian father in the Bronx borough of New York City. The census records although useful, give us an incomplete picture. We find Vivian at the age of four living in NYC with only her mother along with Jeanne Bertrand, an award winning portrait photographer, her father was already out of the picture. Later records show Vivian returning to the U.S. from France in 1939 with her mother, Marie Maier. Again in 1951 we have records of her subsequent return home from France, this time however, without her mother.

Sometime in 1949, while still in France, Vivian began toying with her first photos. Her camera was a modest Kodak Brownie box camera, an amateur camera with only one shutter speed, no focus control, and no aperture dial. The viewer screen is tiny, and for the controlled landscape or portrait artist, it would arguably impose a wedge in between Vivian and her intentions due to its inaccuracy. Her intentions were at the mercy of this feeble machine. In 1951, Maier returns to NY on the steamship ‘De-Grass’, and she nestles in with a family in Southampton as a nanny.

In 1952, Vivian purchases a Rolleiflex camera to fulfill her fixation. She stays with this family for most of her stay in New York until 1956, when she makes her final move to the North Shore suburbs of Chicago. Another family would employ Vivian as a nanny for their three boys and would become her closest family for the remainder of her life.

*

LATER YEARS

In 1956, when Maier moved to Chicago, she enjoyed the luxury of a darkroom as well as a private bathroom. This allowed her to process her prints and develop her own rolls of B&W film. As the children entered adulthood, the end of Maier’s employment from that first Chicago family in the early seventies forced her to abandon developing her own film. As she would move from family to family, her rolls of undeveloped, unprinted work began to collect.

It was around this time that Maier decided to switch to color photography, shooting on mostly Kodak Ektachrome 35mm film, using a Leica IIIc, and various German SLR cameras. The color work would have an edge to it that hadn’t been visible in Maier’s work before that, and it became more abstract as time went on. People slowly crept out of her photos to be replaced with found objects, newspapers, and graffiti.

Similarly, her work was showing a compulsion to save items she would find in garbage cans or lying beside the curb.

In the 1980s Vivian would face another challenge with her work. Financial stress and lack of stability would once again put her processing on hold and the color Ektachrome rolls began to pile. Sometime between the late 1990’s and the first years of the new millennium, Vivian would put down her camera and keep her belongings in storage while she tried to stay afloat. She bounced from homelessness to a small studio apartment which a family she used to work for helped to pay. With meager means, the photographs in storage became lost memories until they were sold off due to non-payment of rent in 2007. The negatives were auctioned off by the storage company to RPN Sales, who parted out the boxes in a much larger auction to several buyers including John Maloof.

In 2008 Vivian fell on a patch of ice and hit her head in downtown Chicago. Although she was expected to make a full recovery, her health began to deteriorate, forcing Vivian into a nursing home. She passed away a short time later in April of 2009, leaving behind her immense archive of work.

*

PERSONAL LIFE

Often described as ‘Mary-Poppin’s’, Vivian Maier had eccentricity on her side as a nanny for three boys who she raised like a mother. Starting in 1956, working for a family in an upper-class suburb of Chicago along Lake Michigan’s shore, Vivian had a taste of motherhood. She’d take the boys on trips to strawberry fields to pick berries. She’d find a dead snake on the curb and bring it home to show off to the boys or organize plays with all of the children on the block. Vivian was a free spirit and followed her curiosities wherever they led her.

Having told others she had learned English from theaters and plays, Vivian’s ‘theater of life’ was acted out in front of her eyes for her camera to capture in the most epic moments. Vivian had an interesting history. Her family was completely out of the picture very early on in her life, forcing her to become singular, as she would remain for the rest of her life. She never married, had no children, nor any very close friends that could say they “knew” her on a personal level.

Maier’s photos also betray an affinity for the poor, arguably because of an emotional kinship she felt with those struggling to get by. Her thirst to be cultured led her around the globe. At this point we know of trips to Canada in 1951 and 1955, in 1957 to South America, in 1959 to Europe, the Middle East, and Asia, in 1960 to Florida, in 1965 she’d travel to the Caribbean Islands, and so on. It is to be noted that she traveled alone and gravitated toward the less fortunate in society.

Her travels to search out the exotic caused her to seek out the unusual in her own backyard as well. Whether it was the overlooked sadness of Yugoslavian émigrés burying their Czar, the final go-around at the legendary stockyards, a Polish film screening at the Milford Theater’s Cinema Polski, or Chicagoans welcoming home the Apollo Crew, she was a one-person documenting impresario, documenting what caught her eye, in photos, film and sound.

The personal accounts from people who knew Vivian are all very similar. She was eccentric, strong, heavily opinionated, highly intellectual, and intensely private. She wore a floppy hat, a long dress, wool coat, and men’s shoes and walked with a powerful stride. With a camera around her neck whenever she left the house, she would obsessively take pictures, but never showed her photos to anyone. An unabashed and unapologetic original.

*

PHOTOGRAPHY

All of the images that you’ll find on this website are not from prints made by Maier, but rather from new scans prepared from Vivian’s negatives. This naturally leads one to the issue of artistic intent. What would Vivian have printed? How? These are valid concerns, the reason utmost attention has been given to learn the styles she favored in her work. It required meticulously studying the prints that Maier, herself, had printed, as well as the many, many notes given to labs with instructions on how to print and crop, what type of paper, what finish on the paper, etc.

Whenever her work has been exhibited, such as for the exhibit at the Chicago Cultural Center, this information is factored in mind to interpret her work as closely as possible to her original process.

*

JEANNE BERTRAND

Jeanne Bertrand was a notable figure in Vivian’s life. Census records list her as the head of household, living together with Vivian and her mother in 1930. Jeanne’s upbringing was similar to Vivian’s – she grew up poor, lost her father while young, and worked in a needle factory in sweatshop like conditions. Yet by 1905 we can read about Jeanne Bertrand in the Boston Globe, being touted as one of the most eminent photographers of Connecticut. What makes this even more surprising is that Bertand had picked up photography only four years prior to that report. But, even if Bertrand was an early influence, it must also be noted that Bertrand was a portrait photographer. Vivian first picked up a camera in the southern French Alps in about 1949. The photographs she took were controlled portraits and landscapes. The odds are strong that Vivian might have been taught by Jeanne Bertrand.

In 1951, Vivian arrived in New York City continuing the same techniques she practiced in France with the same Kodak Brownie camera in 6×9 film format. But, in 1952, Vivian’s work changed dramatically. She began shooting with a square format. She bought an expensive Rolleiflex camera – a huge leap from the amateur box camera she first used. Her eye had changed. She was capturing the spontaneity of street scenes with precision reminiscent of Henri-Cartier-Bresson, street portraits evocative of Lisette Model and fantastic compositions similar to Andre Kertesz. 1952 was the year that that Vivian’s classic style began to take shape.