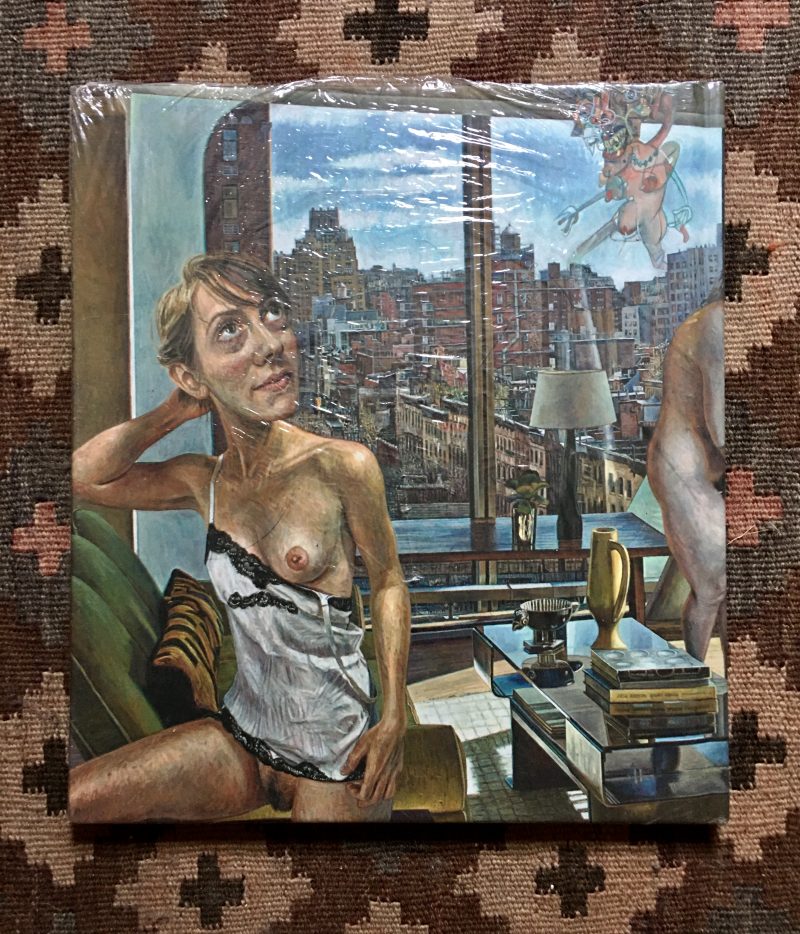

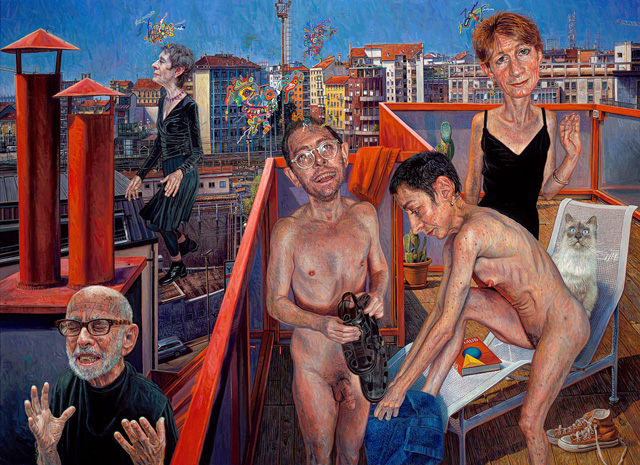

Mark Greenwold, “The Banker’s Daughter ” (2009–2010), oil on linen, 20 x 38 inches (50.8 x 96.5 cm) (all images courtesy Sperone Westwater)

Ever since Mark Greenwold first began exhibiting in 1979, a lot of gibberish has been written about his highly detailed, modestly scaled oil paintings of disquieting domestic situations. One critic, willfully forgetting that there is a difference between fact and fiction, viciously attacked his first solo exhibition — it was comprised of a single large oil painting, “Sewing Room (for Barbara)” (1979) — because the artist depicted a man who resembled himself murdering a woman that looked liked his wife. What would this same critic have made of the six-year-old James’ sudden murderous fantasy about his father in Virginia Woolf’s novel, To The Lighthouse (1927)? I doubt she would have excoriated Woolf. Denouncing Greenwold was easy — he was unknown at the time.

While Greenwold has gone on to gain attention and respect, I feel the criticism, however laudatory, still prefers to deliberately obfuscate the emotional directness of his work. Reviewing Greenwold’s recent exhibition, Murdering the World: Paintings and Drawings 2007–2013, at Sperone Westwater (May 10–June 28, 2013), the artist’s first at the gallery, a critic found it necessary to cite — all in the course of a single review — Sigmund Freud’s first and only visit to America and Franz Kafka’s novel, Amerika (about a land he never visited), alongside references to Balthus Alberto Giacometti, Charles Baudelaire, Marcel Proust, Alain Fournier, Colette and St. Exupéry. Evidently the writer thought Greenwold needed all these names to bolster his work, which he doesn’t.

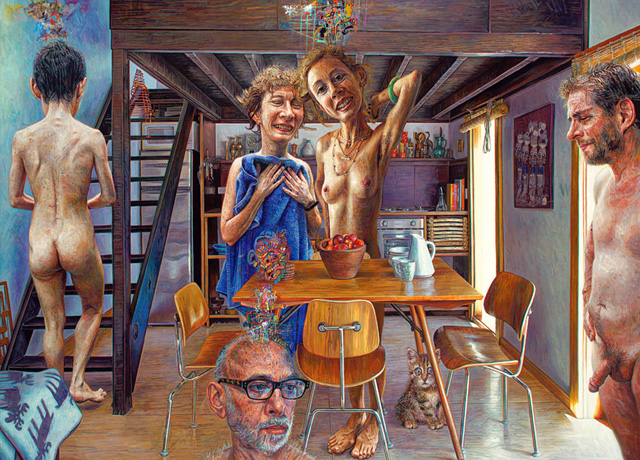

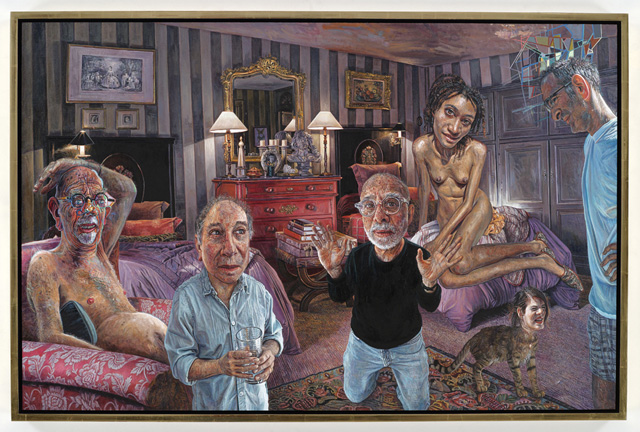

Mark Greenwold, “Men” (2009), oil on linen, 13 ¾ x 22 inches (35 x 55.9 cm)

The simple fact that Greenwold’s work provokes such extreme responses is interesting for many reasons, not the least of which is its ability to touch a nerve that sent these two critics to go either into a near-frenzy of invective, as in the former case, or circumambulation in the latter. Any painter who can do that has got to be up to something, which could explain why Carroll Dunham — who has previously connected himself to Peter Saul — interviews him in the catalog accompanying the exhibition.

What all of these people seem to have forgotten is that a painter makes something to be looked at and, if lucky, talked, thought and written about. But, beyond that, a painter also wants his or her work to be understood and even sympathized with. And for those artists who resist making work that is fashionable, charming, funny or ironic, eliciting sympathy can prove elusive, which seems to be the case with Greenwold’s work. This, I think, is the difficulty that it stirs up. We find it hard to sympathize with middle-aged men and women — who are often naked and not exactly beautiful — crowded together in densely packed rooms, often engaged in some behavior that can be understood only by the people depicted in the scene. But isn’t that what every family or group of close friends is like? Rather insular, but not necessarily closed off, especially to one who witnesses it, which is what Greenwold does. I think we ought to ask ourselves why we retreat from dealing with them.

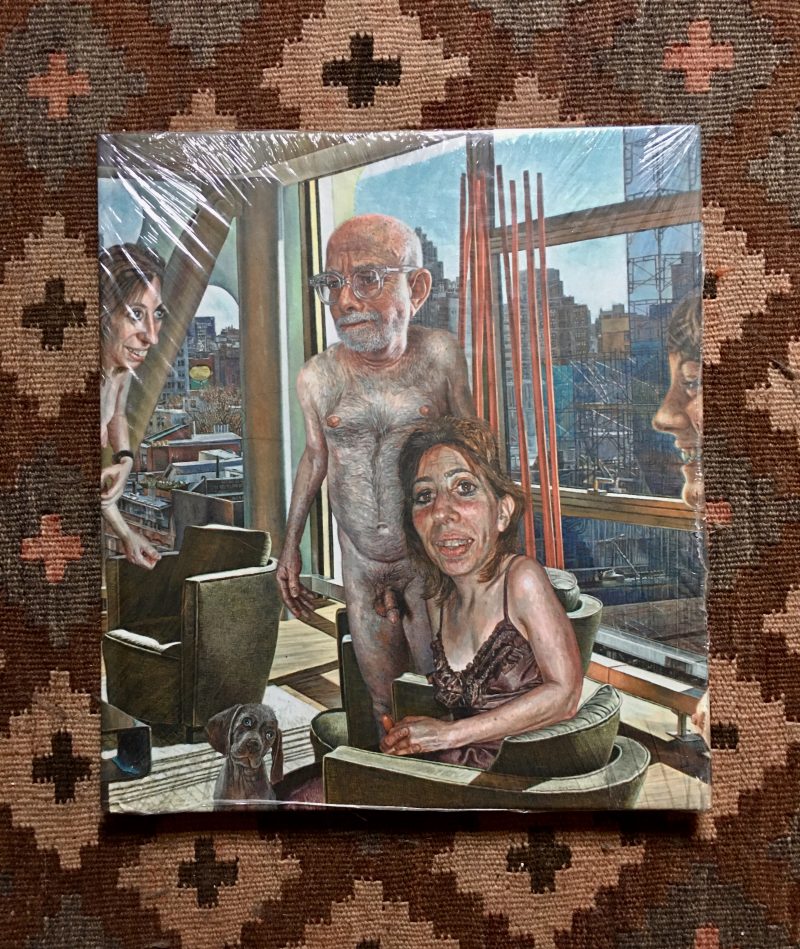

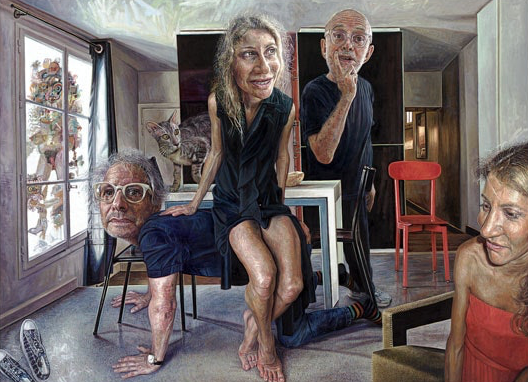

Mark Greenwold, “Human Happiness” (2008–2009), oil on linen mounted on panel, 25 x 34 1/2 inches (63.5 x 87.6 cm)

It is easy to get distracted by Greenwold’s acute attention to the things in his rooms — they are like crowded stage sets full of knick-knacks — or by his inclusion of interlocking abstract elements floating above a person’s head, like an indecipherable thought bubble. But to concentrate on these details would miss a basic feature of the recent work. Nearly all of the ten paintings and four drawings in this exhibition have one telling feature in common: each contain an odd number of people, either five or, in a couple of instances, three.

As he has done so thoroughly and even aggressively from the outset of his career, Greenwold is here again challenging conventional thinking about autobiography and transparency. It is easy to be literal-minded about these works and think that the recurrent figure resembling the artist is Mark Greenwold, too easy. As the artist takes pains to suggest in the interview: “Roth’s books, Tolstoy’s books, they’re all about their own lives reimagined.” However rooted the works may be in Greenwold’s own life, they are not about him. They are about us, with particular attention paid to being a witness, the extra wheel, the sharp-eyed observer whose powers of observation create feelings of alienation. They are about not being part of a couple at a gathering of couples. They are about growing old and the feelings of helplessness, terror and — yes — even joy that it induces.

In “Human Happiness” (2008–2009), four people appear nearly full length and nude in the foreground of a narrow kitchen of what seems to be a summer house with an upstairs loft area. The fifth figure is just off center, his head visible at the bottom left of the painting, with the rest of his body from the neck on down cropped by painting’s physical edge. An intricate, brightly colored conglomeration of lines rises from the figure’s bald pate, culminating in a distorted mask-like face — with its tongue sticking out — made of interlocking and overlapping linear elements that recall the vocabulary of abstract forms used by Greenwold’s friend, the painter Chuck Close.

One figure – whose gender is not clear — ascends the stairs on the far left. Two nude women — one of them, with her eyes closed, clutches a blue towel in front of her — stand in the center of the painting, facing the viewer. Both are smiling, mouths open. On the far right, a nude man faces into the room, his eyes closed, in reverie.

Mark Greenwold, “O Troubled Heart” (2007–2008), oil on linen mounted on panel, 24 x 33 inches (61 x 84 cm)

The fifth figure popping up at the bottom left upsets the symmetrical balancing of the four standing figures. What is he thinking about? Are the watery blue reflections in his glasses meant to evoke tears? I think Greenwold’s attention to surfaces, from freckled, wrinkled, sagging and hairy skin to shiny glass tabletops, polished steel refrigerator doors and glowing wood veneer, points up the mortification we encounter as the inanimate world stays the same while we, the living, continue to age and inevitably degrade.

By juxtaposing three distinct vocabularies (or realities) — aging, middle-aged flesh, perfect surfaces and intricate, brightly-colored linear configurations — Greenwold brings together the rational and irrational, order and disorder, the factual and the fantastic, without privileging any one of them above the other. However much we’d like to think otherwise, our lives don’t simply add up.

The world Greenwold depicts is contentious, convivial, estranged, raucous and democratic. He celebrates and laments it in equal measure. Greenwold could have chosen to become a celebrated cult figure by restricting his personae to animals with human heads, a number of which have appeared in his paintings. Instead, he decided he wanted to paint it all. He didn’t want to become his generation’s Ivan Albright and he is the better artist because of it. He courts garishness and grotesquerie, but he never crosses the line into caricature. He can paint a big toothy smile that is also a painful grimace; he is that attuned to human expression. He is on the opposite end of the spectrum from the autobiographical stylizations of Alex Katz, but hasn’t gotten nearly the same amount of attention and, frankly, he should.

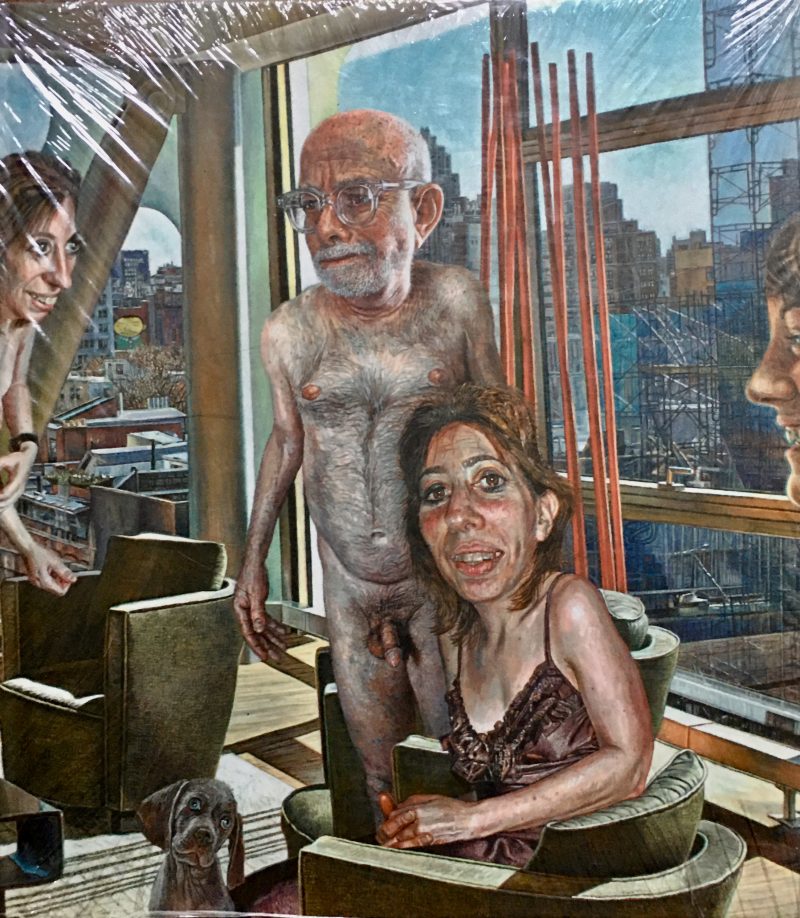

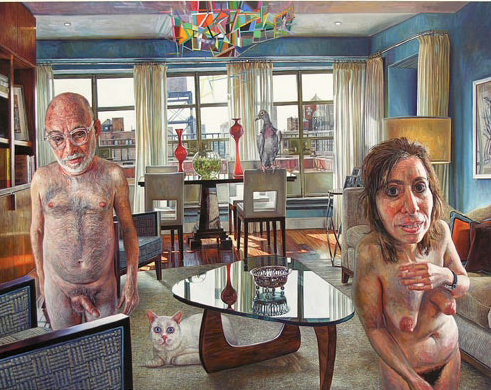

Mark Greenwold, “As a Man grows Older” (2010–2011), oil on linen mounted on panel, 26 x 40 inches (66 x 101.2 cm)

In the middle of “As A Man Grows Older” (2010–2011), the artist depicts his doppelgänger on his knees, his palms facing us in supplication. It is a gesture at once plaintive and vulnerable. Greenwold knows he can shape time, tiny brushstroke by tiny brushstroke, but he cannot stop it. And neither can we.

I don’t know of another painter who can paint aging flesh, down to the deep wrinkles and liver spots, with such tenderness. Certainly not Alice Neel, for whom tenderness seemed not to be an option. Consider the generation of Pop artists who sought refuge from time passing in a coolly objective style full of obvious charm and immaculate surfaces: Roy Lichtenstein, and lesser figures such as Tom Wesselmann, and Mel Ramos. It is this institutionally renowned way of making art, in which the artist makes signature products rather than sees and thinks his or her way through time, that Greenwold refutes in painting after painting. He cannot stop looking at the world of friends and acquaintances, no matter what terrifying sights and thoughts such scrutiny brings. You have to have courage and curiosity to look that closely and carefully at what times does to the body, to admit the thoughts percolating in one’s mind. Greenwold had them right from the beginning.

Mark Greenwold: Murdering the World, Paintings and Drawings 2007–2013

continues until June 28 at Sperone Westwater (257 Bowery, Lower East Side, Manhattan).