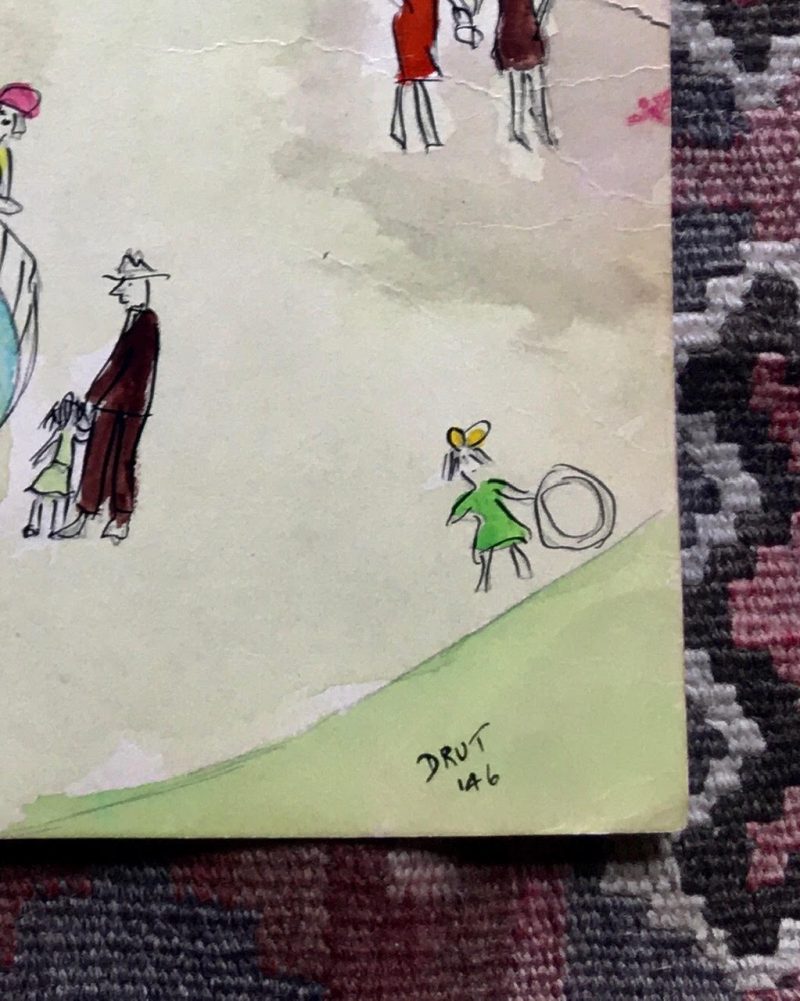

Mid Century Watercolor Drawing ‘Central Park Zoo’ 1946

Mid Century Water Color Drawing of the famous Central Park Zoo. ‘Restaurant Terrace and Seal Pool / Central Park Zoo N.Y.C’. Signed & dated ‘DRUT ’46’ at lower right of artwork. Measures 14 x 11 inches. Small tear at middle right side; easily hidden once framed. Paper is aged but otherwise in good condition. Part of estate of mid century artworks & archives, acquire din New York in the ealry 1990’s. See deatiled information on the zoo, and the exact same view of the seals, in info below.

Verbally appraised at USD$525.

History of Central Park Zoo

Although the Zoological Society of Philadelphia chartered the Philadelphia Zoo 35 years before the New York Zoological Society was established, Central Park’s zoo may be the oldest municipal zoo in the United States, and today the Central Park Zoo is one of the most-visited features in the park.

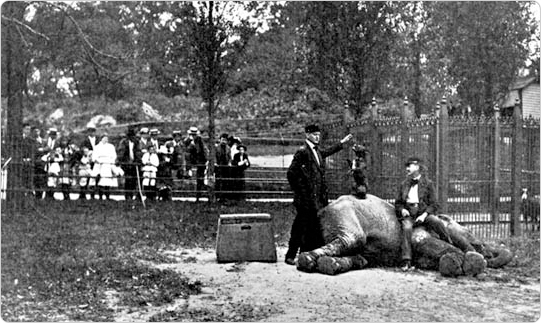

Animals have been exhibited at Central Park from nearly the very beginning of its history, starting with a bear cub left in the custody of a park messenger boy, Philip Holmes, shortly after construction of the park began in the late 1850s. Holmes took care of the bear, and before long a temporary collection of animals grew in and around the park’s headquarters at the Arsenal. Central Park’s original plan designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux excluded a zoo, but park commissioners responded to the ad hoc housing of animals by seeking a location for a “menagerie” that would not compromise the park’s pastoral landscape. State legislation in 1861 authorized that a “portion of [Central Park], not exceeding sixty acres [be set aside] for the establishment of a zoological garden . . .” Vaux prepared a plan for Manhattan Square, today the site of the American Museum of Natural History; Olmsted suggested moving the menagerie to the park’s northwest portion and placing paddocks for grazing animals dispersed around the park; the commissioners authorized, and then halted construction of a new menagerie at the north meadow. After a dozen proposals, during the 1860s the animals took up permanent residence behind the Arsenal, as if by squatter’s rights. Victorian-styled structures sprouted up on the grounds under the direction of William Conklin, the Menagerie’s director from the 1860s through the 1880s. The Menagerie was also the scene of rare births in captivity, such as a South American peccary born in 1866. The public responded enthusiastically to the menagerie; daily attendance was 7,000 people by 1873, and annual attendance by 1902 was reported at three million.

Exotic Donations

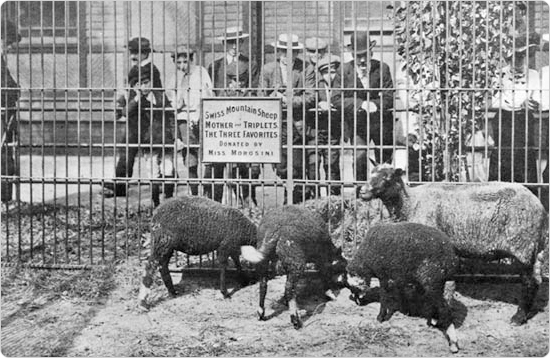

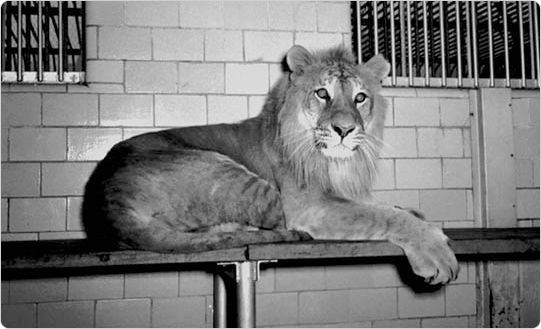

From the 1860s to 1890s, prominent citizens such as financier August Belmont and inventor Samuel Morse donated various animals; General Custer gave the zoo a rattlesnake, and General Sherman offered an African Cape buffalo, one of the spoils of his march through Georgia. One of the zoo’s most exotic donations was a “tiglon” that was donated to the City in 1938. Charles the Tiglon was the offspring of a female African lion and a male Siberian tiger, the combination of which being more rare than a “liger,” which is the offspring of a male lion and female tiger.

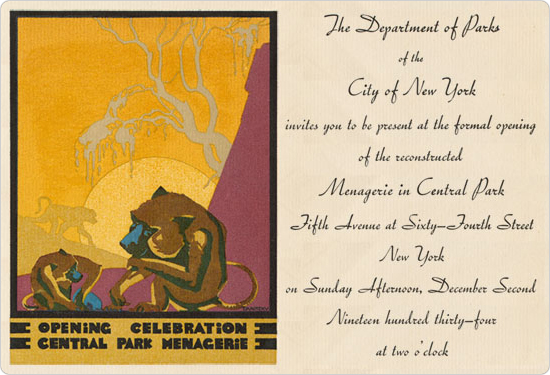

Yet despite improvements made around 1900 to improve the care and environment, the animals’ best interests were not always served. In 1934, however, Parks Commissioner Robert Moses addressed adverse conditions in the menagerie by stressing that only healthy animals in more humane circumstances would be displayed. The new brick and limestone “picture-book zoo” was designed in just 16 days by an in-house design team headed by Aymar Embury II. Construction on the roughly six-acre zoo took only eight months, helped along by federally financed Works Progress Administration (WPA) labor.

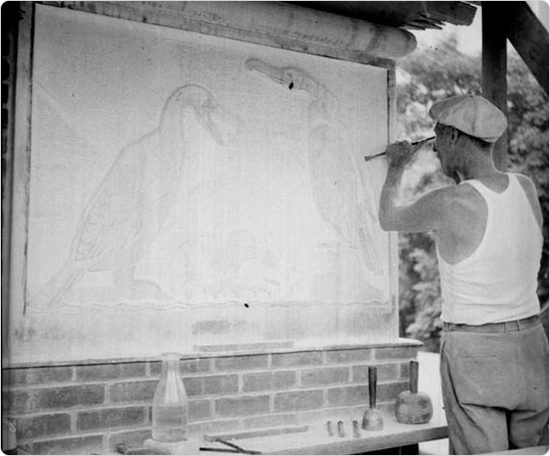

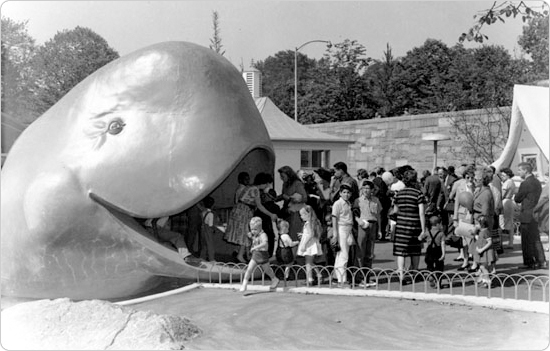

The zoo opened with great fanfare on December 2, 1934, and former Governor Alfred E. Smith was designated honorary zookeeper. A big fan of zoos and Central Park Zoo in particular, Smith, who lived at 820 Fifth Avenue just across from the zoo, referred to himself as the zoo’s “night superintendent.” The zoo was structured as a quadrangle with a sea lion pool at its center (one of several elements from the 1934 zoo that still exists.) Additional bird and monkey houses flanked the Arsenal to north and south, and a large restaurant, known as Kelly’s Restaurant, stretched along the back. An elaborate program of animal art included a bronze dancing goat and bear by Frederick G. R. Roth, limestone reliefs and a painted mural by Roth and his assistants, and wrought-iron weathervanes by sculptor Hunt Diederich. The eight eagles around the sea lion pool were installed at the zoo in 1941.

Sea Lion Pool Eagles

Although they look like they could have been part of the fa?ade of the original Penn Station, the eight granite eagles actually come from an overpass in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn. The 1st Avenue overpass was built in 1912 in connection with the Shore Road parkway. The eight eagles originally sat atop piers on the overpass. When the bridge was demolished in 1941 to accommodate a larger Belt Parkway, the eagles were transferred to the Sea Lion Pool at the zoo. The provenance of the eagles was largely unknown until researchers working with the Parks Department Photo Archive uncovered photographic evidence of the eagles in their original spot, and the Parks Monuments division discovered a cryptic journal entry from 1941 that noted an unnamed administrator directed the Monuments division to install the eagles at the zoo.

Despite the often primitive quarters of the animals, zookeepers recall establishing strong emotional bonds with the animals in their care. One read the newspaper everyday to a chimpanzee. Others recall fondly the time a capuchin monkey escaped his confinement and ran across Fifth Avenue to hide in the bimah of Temple Emanu-El at 65th Street. Eventually, however, no amount of love and attention could save the zoo from falling into disrepair, and the zoo became what many found to be a squalid place—Fifth Avenue tenants complained about the noise and smells, and others found the succession of spare cages depressing. Opposition increased in the 1960s, and by the 1970s it was clear that this zoo had outlived its usefulness. Parks Commissioner Gordon Davis, during whose tenure the operation of the zoo was transferred to the New York Zoological Society, was embarrassed by the state of the zoo (he later called the facility a “Rikers Island for animals”), especially after taking his young daughter to the zoo shortly after becoming commissioner and having her beg him to never again bring her there.

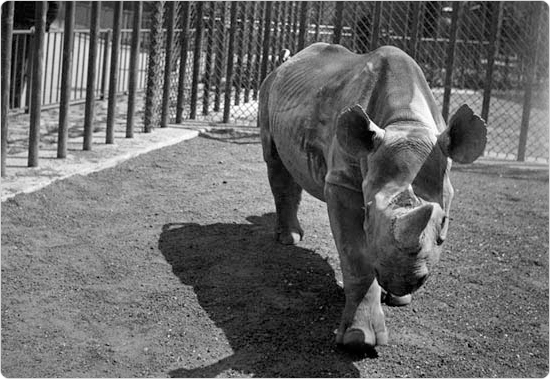

Economic conditions and public opinion came together to force the City to make a drastic decision about the future of not only Central Park Zoo but also the facilities in Prospect Park and Flushing Meadows Corona Park, and in 1980 Parks entered into an agreement with the New York Zoological Society (today the Wildlife Conservation Society) to manage all three City-run zoos. Although the deal gave concession rights to the Society, the three zoos required a great deal of private financing, and several big backers emerged, including Lila Acheson Wallace, the cofounder along with her husband Dewitt of Reader’s Digest (the Wallace Foundation has given billions of dollars to charitable causes). Although nearly everyone agreed that it was inhumane to keep large zoo animals in such a small zoo, what to do with the new facility was an open question. Some advocated for a model farm, where city kids could see domestic rather than exotic animals (in effect reprising earlier ideas dating to the farm gardens in the 1910s and 1920s and the mobile farm gardens in the 1950s). Another idea was to convert the zoo to an insect zoo, which was quickly abandoned in the face of the public’s fixation on large animals. In the end, the zoo was pressured to keep the polar bears and sea lions (the sea lion pool in fact became a little bigger), but most of the larger animals like zebras, bears, and elephants were transferred to other zoos.

Because the site was so small (roughly six acres compared with a national zoo average of just over 52 acres), the New York Zoological Society tried a new approach; large animals were given more space or removed altogether. But the biggest change was the removal of the cages, and the talk of the day was all about “making the zoo barless.” Removing cages also meant that the Society could organize the animals around a more holistic premise than size: in 1941, the Society pioneered the principle of exhibiting animals by continents, and with the Central Park Zoo they decided to maintain the quadrangle layout of the 1930s zoo while adopting a plan of three “biomes”—tropical, temperate, and polar. Architect Kevin Roche, who also devised the master plan for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, integrated old and new elements while conforming to contemporary principles of animal care. Roche was suggested by Wallace, and the pick initially was seen as unorthodox; he had designed not only the Met but also the three United Nations Plaza towers and the Ford Foundation headquarters on East 42nd Street but never a zoo facility.

The last animals were removed in November 1982 and demolition, except for four perimeter buildings, began in February 1983. There was a ceremonial groundbreaking for the new zoo on February 10, 1984 and construction began April 8, 1985. The park’s reconstruction was accomplished through some amount trial and error: for example, the fake rocks of the sea lion pool, which took several tries to get right, and an aeration mechanism having to be added to the moat surrounding the snow monkeys after several escaped when the water turned to ice during a cold spell. But when the zoo reopened on August 8, 1988 after a 5-year, $35 million renovation, the new facility delighted visitors with its naturalistic tropical zone, expanded polar bear environment, and Japanese snow monkey island.

The historic artwork was incorporated into the facility, either relocated or remounted on the buildings, as in the case of the Roth friezes. The sea lions exhibit, a theater in the round, remained. Several of the buildings that stayed simply changed their function: the Bird House became the Zoo Gallery and Gift Shop, and the Monkey House became the Zoo School as well as a premier event space. The spot where Kelly’s Restaurant sat was reborn as an environment for snow monkeys. 4,000 square feet of planting beds were laid out by landscape architect Lynden Miller, whose challenge was to come up with year-round plantings for the year-round facility, and to that end, she focused on various species of trees and shrubs, as well as special summer flowering plants. And for the first time in the city’s history, the zoo charged an admission, which many lamented: $1 for adults, 25 cents for children three to 12. The admission fee also had the effect of blocking an important east-west access point at the park, changing the way park visitors circulated through the space.

Notable Central Park inhabitants have included “Fin” the sea lion and the Gus, the zoo’s moody polar bear (he was given behavioral therapy for his apparent malaise). Two penguins made a contribution to the so-called culture war in the U.S. when the public began to notice the coupling of two male birds, Silo and Roy, who (adopted) and looked over a baby penguin chick. Silo eventually left Roy for Scrappy, a female bird from SeaWorld.

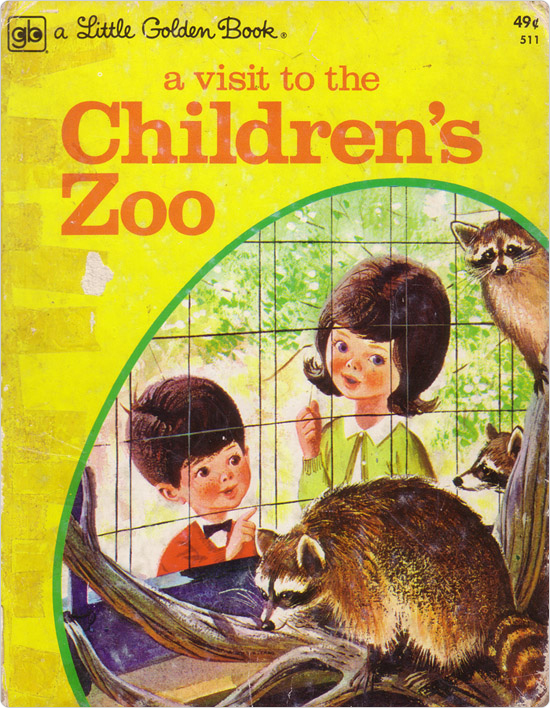

Central Park Children’s Zoo

A Children’s Zoo was established at Central Park in 1961, funded in large part by Senator Herbert H. Lehman and his wife Edith Lehman, who in celebration of their 50th wedding anniversary, donated $500,000 towards the cost of the zoo. The zoo featured llamas, pigs, penguins, cows, a monkey, and white mice; a petting area with ducks, rabbits, and chickens; a Noah’s Ark feature; and a medieval castle feature. The zoo was renovated in the 1990s, reopening in 1997 with a different layout and objective, but not before dueling camps of preservationists “locked horns” on the issue of whether to preserve the distinctive 1960s pop architecture or switch to a design more in keeping with Olmsted and Vaux’s original view of the park.

The Olmsted and Vaux preservationists persevered in the end, and the new Children’s Zoo became more integrated into the park’s design. Several fanciful features were given to the Museum of the City of New York, and Wilhelmina the whale was salvaged as part of a public art project by the Rockaway Artists Alliance in Queens. Another controversy ensued when philanthropists Edith and Henry Everett withdrew a $3 million gift after the Art Commission refused to approve a design that omitted the original Lehman name on the ornamental Manship Gates. The story had a twist when the Tisch family, a rival of the Everetts, stepped in and raised their $3 million gift to $4.5 million. Quennell Rothschild & Partners designed the new children’s zoo, with naturalistic features and notably a massive net covering the entire zoo, which allows birds to fly freely. The firm also provided many interactive features in the redesign, while preserving Paul Manship’s gates.