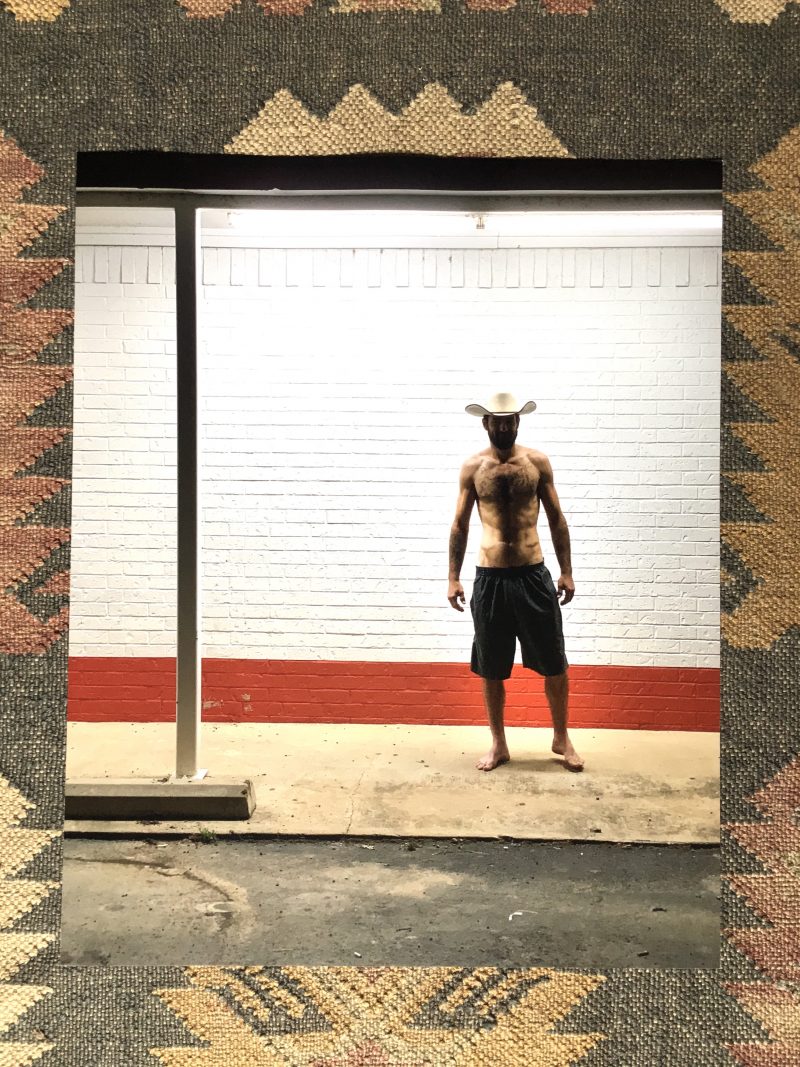

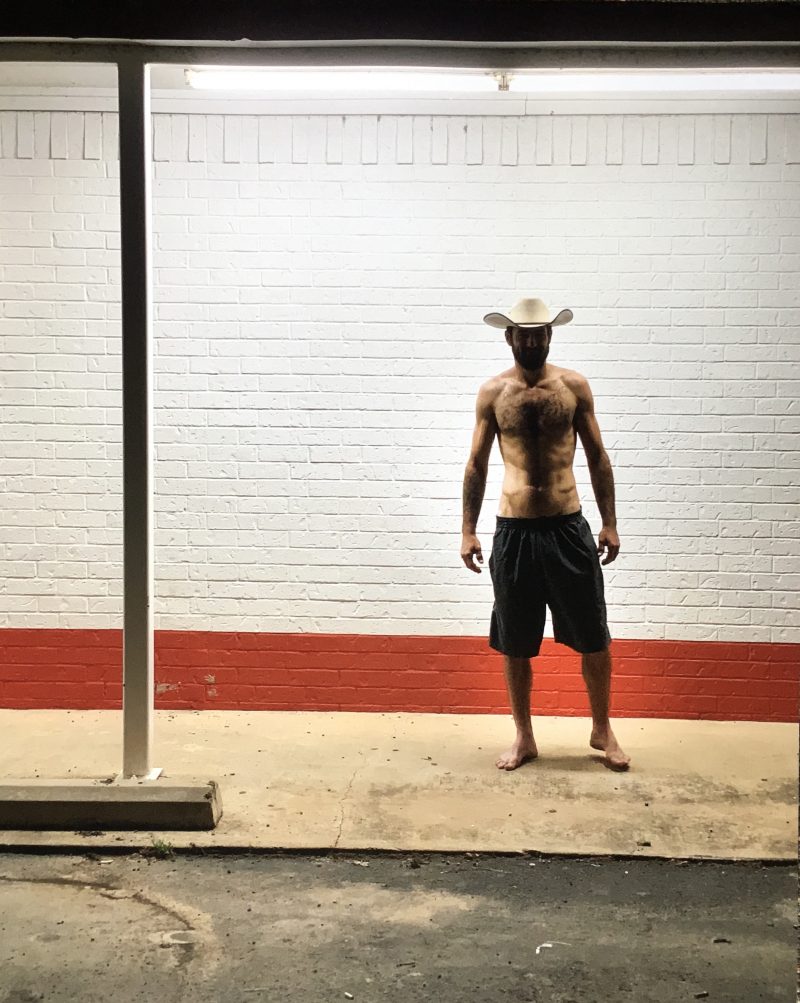

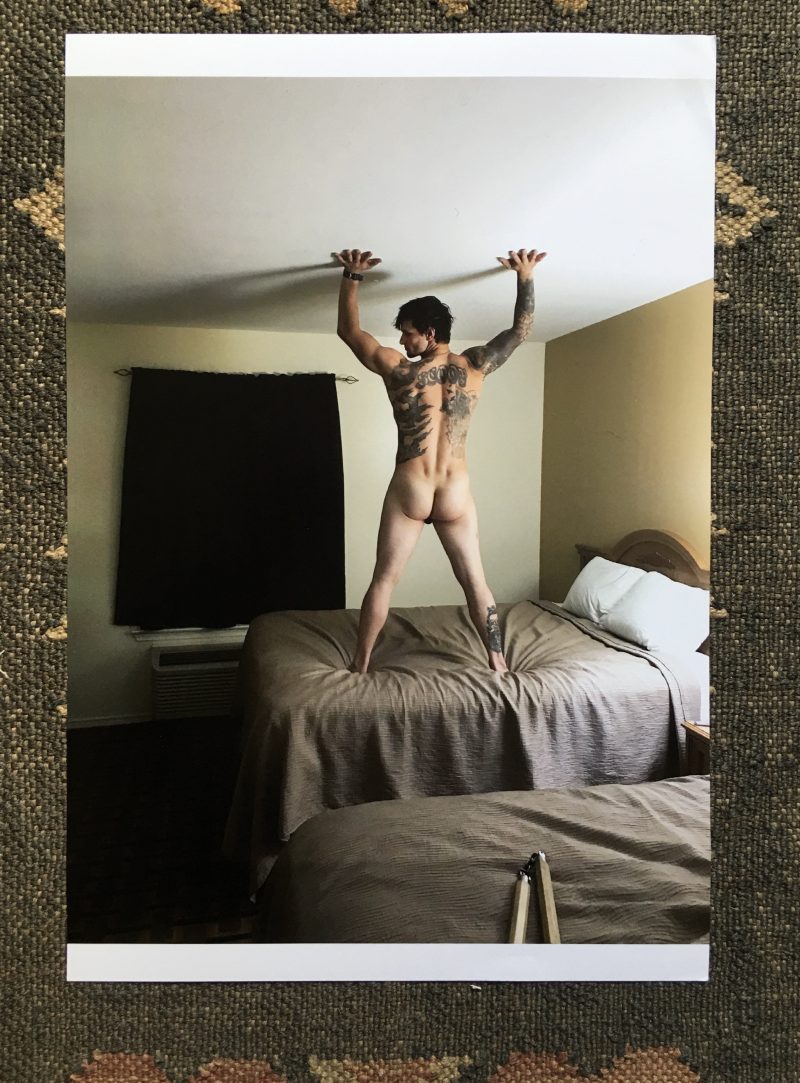

Photographs by Chivas Clem, Paris, Texas, USA

17 October 2024 – 12 January 2025

A native of Paris, Texas, Chivas Clem returned to his hometown more than a decade ago after an illustrious early career in New York. After completing the Whitney Independent Study Program and being an essential part of august institutions such as Artforum and American Fine Arts, Clem made the radical move back to Texas. While his earlier art practice explored the psycho-sexual underbelly of American pop culture, Clem turned his attention to his native landscape, its forgotten population, and the mythos of the Southwest. His voracious camera began documenting a male subculture he encountered in Paris.

INTERVIEW with Jack Pierson for Interview Magazine:

CHIVAS CLEM

LIVES AND WORKS IN PARIS, TX.

A native of Paris Texas, Clem is a graduate from the prestigious Whitney Independent Study Program. During more than a decade in New York, Clem is known for launching the influential artists space The Fifth International, which championed the work of AaronCurry, Alex Bag, Jonathan Horowitz and others.

Clem’s work has been exhibited widely in the United States and Europe including Deitch Projects in New York, Dallas Contemporary, and Galerie Almine Rech in Paris. His work is in the collection of the Museumof Modern Art, The Centre George Pompidou in Paris, and private collections in the United States and Europe. Clem is currently represented by the Maccarone gallery in New York and Los Angeles.

Artist Statement:

After living in NYC for 12 years Chivas Clem moved back to Paris, Texas, his hometown near the border of Oklahoma. His multidisciplinary practice started to focus on documenting his relationship with a group of so-called “rednecks” -rough rural white men indigenous to NE Texas. Much in the same vein as Larry Clark, Clem entered their world. He began to hire them at the studio and they allowed him total access to their world- he shot them naked, getting stoned, sleeping, smoking, bathing. Feral and dissolute, but also sensitive and gentle, the sitters’ aggressive exterior functions as a kind of emotional camouflage. While many of them are felons, addicts, and drifters- the subjects exude a mien of both corruption and innocence and he imbues this ambivalence with a rough sensuality and pathos. The small gestures of an arched back or a sun-kissed neckline trace the outline of these precarious bodies. The effete exterior hides an opaque fragility – fierce, searching, and stark. Clem saw in this unexamined subculture a connection to the myths of the rugged masculinity of the “cowboy”, now devolved into something more bitter and tumultuous- certainly connected to more socio-political themes around the rise of fascism in America. Portraits and nudes of his models are mixed in with images of broken phones, dirty hands, and wilting magnolias, tropes of the decaying south, often shot against the backdrop of a victorian property that has become his makeshift studio.

Clem has said “I grew up gay in this place -a small town in the deep south, and these were the kinds of men that made my childhood miserable. Now they are the only people I relate to, as I see them as outsiders themselves. Perhaps the twin feelings of desire and fear that gave them so much psychic power in my youth is the origin of this fascination.” Clem’s bond with his sitters became so strong he did not return to NYC.

There is a deep south colloquialism for a relationship that supersedes friendship. “Shirttail Kin” is someone you are kin to by affection not by blood. Clem returned to his hometown to discover his new kin- his “Shirttail Kin”. These are the pictures he took of them.

Exhibitions:

2021

ART IN REVIEW; Chivas Clem

Feb. 6, 2004

Gallery Maccarone

45 Canal Street, Lower East Side

Through Feb. 22, 2004

Mass media celebrity is a phenomenon so fantastic and bizarre that art can do nothing more effective with it than frame existing images, as Chivas Clem does in this mordant solo show. Most of his images are photographs culled from journalistic sources and gain a certain weight and mystery recycled in a gallery setting.

A woman who looks blindfolded or veiled — she brings to mind figures dressed in burkas or the mourning Jacqueline Kennedy — is actually Monica Lewinsky, her face obscured by a baseball cap bill. A newspaper photograph of a captive Taliban hangs beside an auction catalog reproduction of Andy Warhol’s portrait of O. J. Simpson. In both pictures the subjects are bearded and stare intently into the camera, and their pairing stirs up interesting ideas about the slipperiness of categories like aggressor and victim.

Criminality is a recurrent subtext in the show, linked to homosexuality and art. A photographed portrait drawing of the serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer incorporates a drawing of van Gogh’s ear. A shot of art books on shelves was taken in the apartment of Andrew Cunanan, the murderer of Gianni Versace. Mr. Clem gives the title ”Self Portrait” to a film still of the transvestite killer from the film ”Silence of the Lambs.”

And he appears himself in the show’s one video, where he is seen hurling himself into the path of a subway train. The video is a shrewd update on the famous photograph of the artist Yves Klein apparently performing a suicidal swan dive from a rooftop. It is also an enactment of a subway suicide that Mr. Clem witnessed last summer. In his film version, a terrible act of real-life self-destruction is replayed as a fiction within a fiction on a much-diminished contemporary version of the silver screen.

** INTERVIEW: BUTT Magazine:

MORE:

Sex, death and Mountain Dew: Artist Chivas Clem offers a splash of optimism

The Texan’s dye-themed works are part of a group show at Erin Cluley Gallery.

Chivas Clem on Cowboys, Caricatures, and Cracks in the American Dream

Growing up in Texas, Clem harbored a deep-seated phobia of men and boys, a fear rooted in the South’s rigid norms of masculinity. His work today reflects both a confrontation with that past and an attempt to dismantle the very archetypes that once terrified him. Though Clem forms close relationships with his models, his perspective is different from Clark’s. While Clark was fully embedded in the lives of his subjects — living, using, and suffering with them — Clem remains both insider and outsider, woven into the fabric of Paris, Texas, yet at a careful distance from the precarious lives of the men he photographs. Shirttail Kin tackles broader American anxieties, particularly the “redneck” stereotype often entangled with racism, homophobia, and violence. Clem’s work challenges these assumptions, offering a glimpse of the fragile humanity that persists beneath the cultural caricatures.

Ahead of the opening, I called Clem from New York. He answered from his dilapidated home-studio in Paris, Texas, where many of these photographs were taken. We spoke about Southern masculinity, reconciling with his childhood phobia, the serendipity of meeting his models, and how his work balances despair, darkness, and innocence.

Hi Chivas, how’s it going?

Chivas Clem— It’s going okay, I guess. I’m ready for summer to be over kind of.

I feel the same way.

It’s miserable in Texas. It was like 113 degrees in my car the other day.

That’s awful.

No, it’s gotten really insane. I grew up here and when I was a kid, it was never like this. It was hot in the summer, but it wasn’t like this.

I grew up in New York, and I feel like that about our summer thunderstorms. They were never as crazy as they are now.

Yeah. It’s true!

When I first saw some of the photos in Shirttail Kin I had a visceral reaction, I teared up at some of them.

Oh, God. I’m so happy to hear that. People have such dramatically different reactions to the work. Occasionally I’ll show the work to somebody, and they’re very moved by it, even to tears, and then sometimes I show it to people and they see it as soft-core pornography.

I had a show in Houston a couple of years ago with Bill Arning, and Bill caught this guy masturbating in the gallery, which is kind of flattering in a way. I mean, I can’t imagine that happening at David Zwirner.

Yeah, probably not. I didn’t view the photographs as pornographic. What resonated most was the act of seeing these men, depicting them through your lens, and now, exhibiting the images in a show at Dallas Contemporary. There’s this American subculture that’s deeply marginalized and this project, its placement, defies that.

People don’t talk about that with the work that often, but it is very much about them feeling seen. A huge part of my work is building this sense of intimacy with them so that they’re comfortable with me. It all happens very organically, I’ve never done a formal audition or anything, and they’re all just local people that I’ve met. I met one of them at a gas station, and another while hitchhiking, and I’ve cultivated friendships with all of them. A lot of them sit for me over and over again.

Having grown up in a place where masculinity was rigidly defined and often weaponized, how do you think your Texan roots shaped not only your artistic lens but also your understanding of the men you document in Shirttail Kin? Does the work, in a sense, reflect your own reconciliation with that past?

Well, when I was a child I actually developed a terrible fear of men and boys, so severe that I actually had a therapist who wrote a note to the school that I could not take boys’ phys ed so I was transferred through junior high as a girl for a few years, which was very confusing for everybody but me. I couldn’t step into the boys’ locker room without having a meltdown.

I grew up around rednecks and had this terrible fear and fascination for them. And erotic fixation, which I didn’t discover until later on. I still live in the country north of Dallas, and that’s still how everybody here is.

America is witnessing a crisis of masculinity right now, which has been growing since the women’s movement and the gay rights movement. There’s this hysteria amongst the right over men who dress in drag that it’s some kind of humiliation ritual. I wanted to look at old-fashioned masculinity with a fresh set of eyes. What I found here is that these men are really wearing their own king of drag, clinging to their own understanding of masculinity. That was very interesting to me.

There’s a long history of photographers who have looked at cowboy archetypes, like Danny Lyons and Larry Clark, but I feel like that archetype’s dated now — it’s not as relevant. There aren’t any real cowboys anymore; it’s been reduced to an aesthetic. If the cowboy archetype represented rugged individualism, then what it’s become, if it’s the image of the redneck, is a deplorable person, racist, homophobic, all of the above.

I wanted to show the humanity in these guys. It’s funny, originally I didn’t want to call the show “Shirttail Kin.” A friend of mine said that I should call it “We Found Love in a Hopeless Place.”

Given the often deeply ingrained societal norms around masculinity that exist, especially in the rural South, how do you see their lived experiences reflecting broader cultural narratives in America today?

What people don’t realize is that the living conditions are often way worse than you could imagine. You can’t imagine the environments some of my models grew up in. There’s one whose parents abandoned him in a house when he was 12, and he kept living there alone, with nowhere else to go. He had neighbors who would bring him food occasionally. Some had it way worse. And of course, they grow up filled with so much rage and anger, but also fear, so many of them are terrified. It’s absolutely like witnessing the return of the repressed.

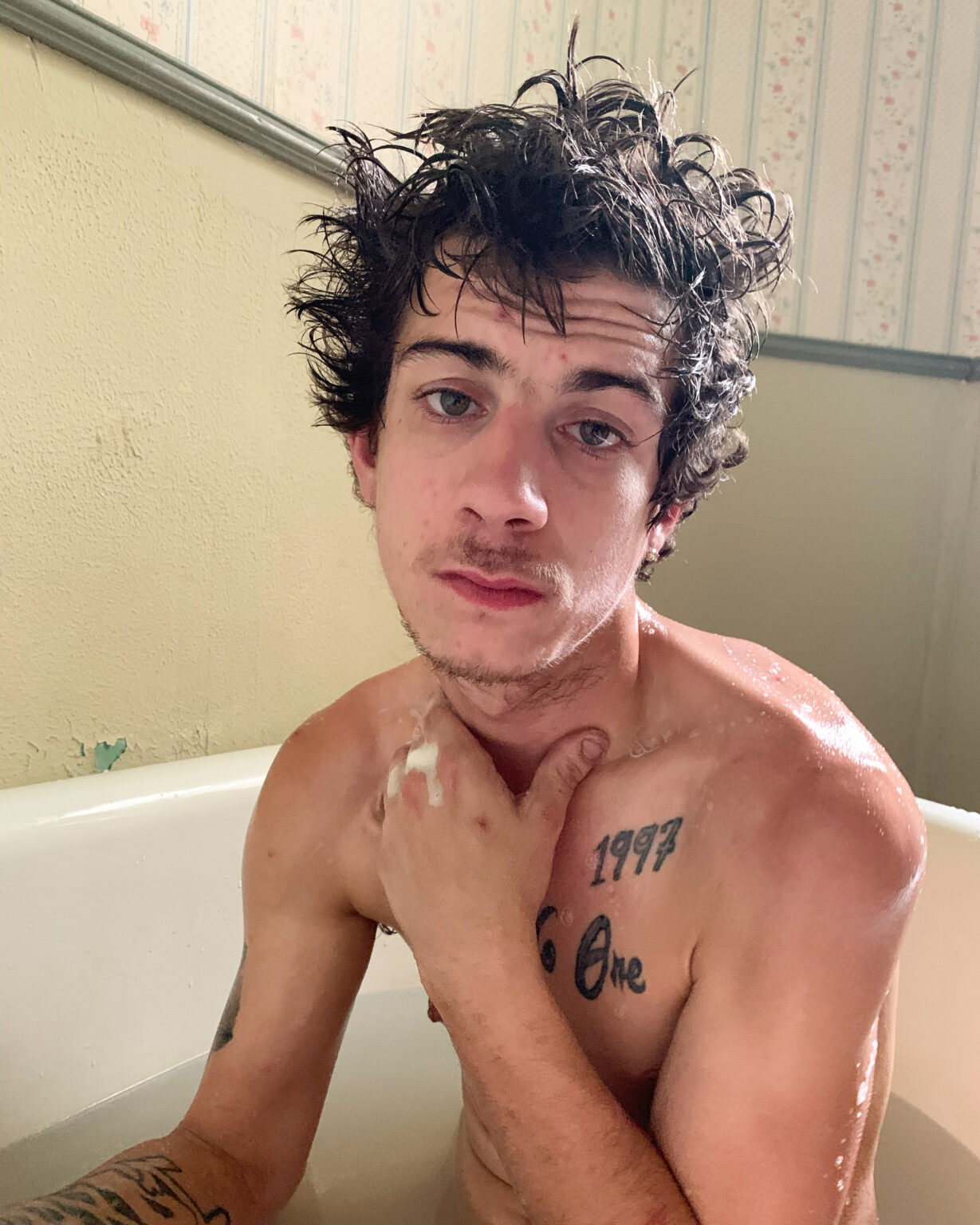

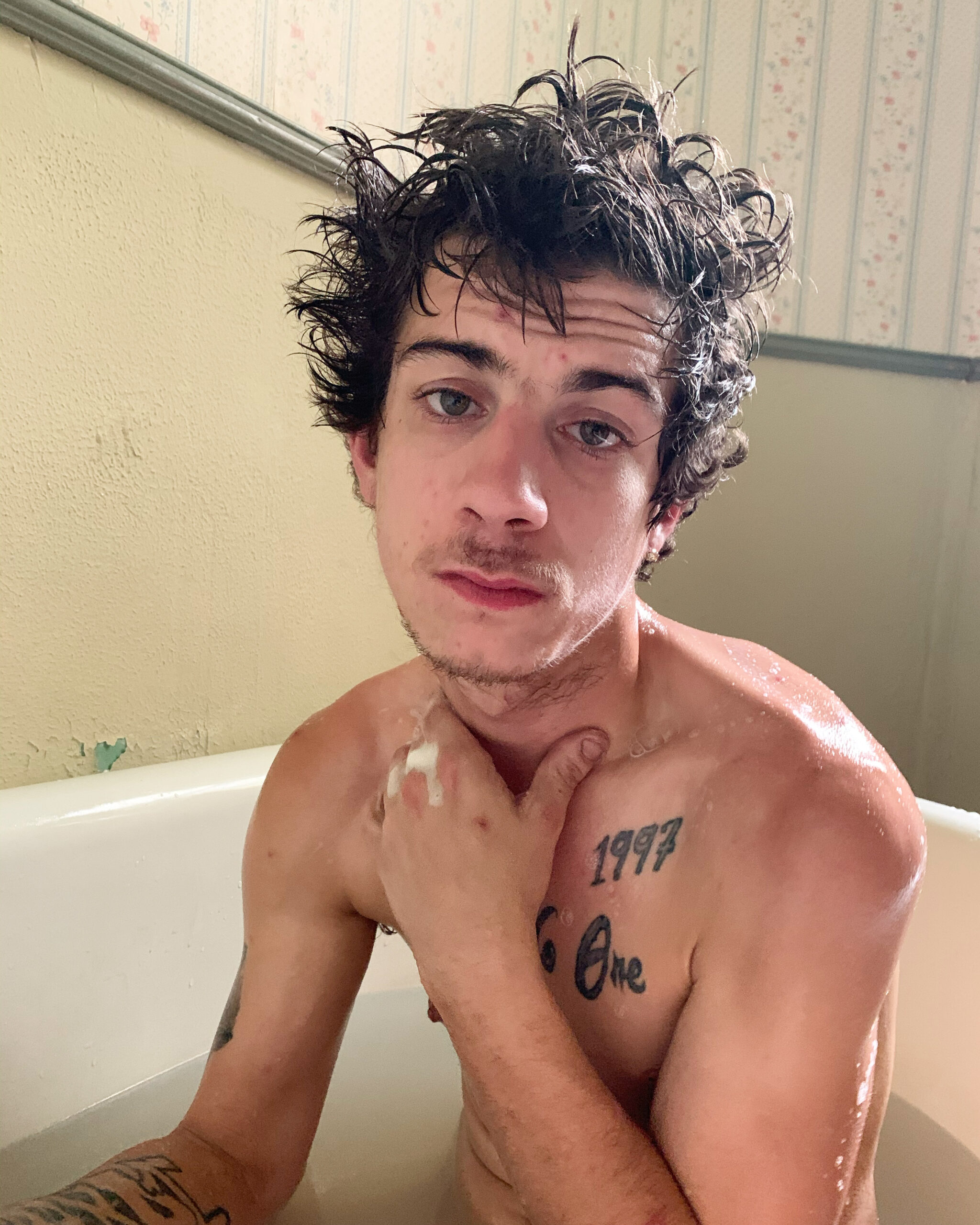

Chivas Clem, Coty in the Bathtub after Breaking In, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Dallas Contemporary.

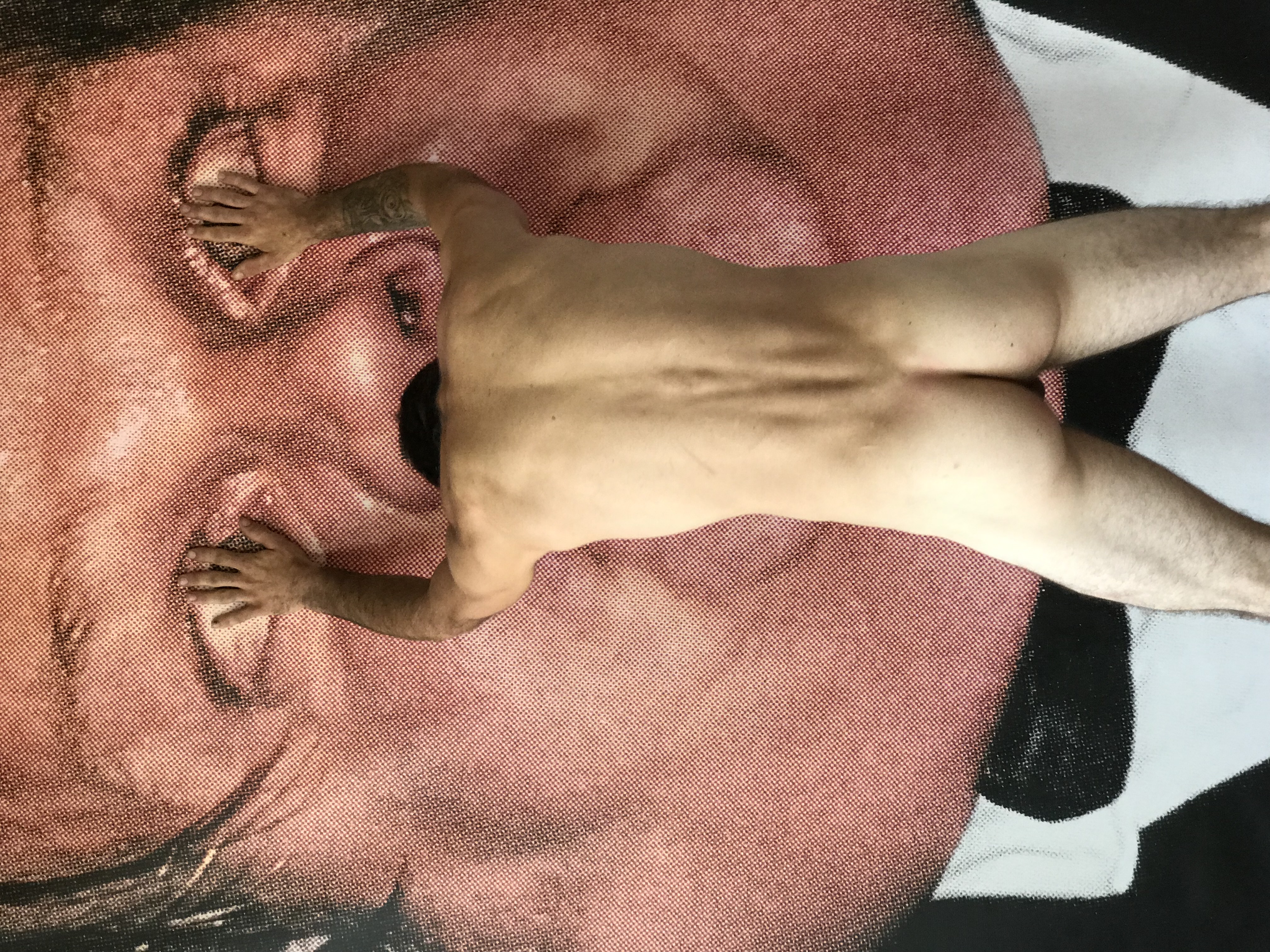

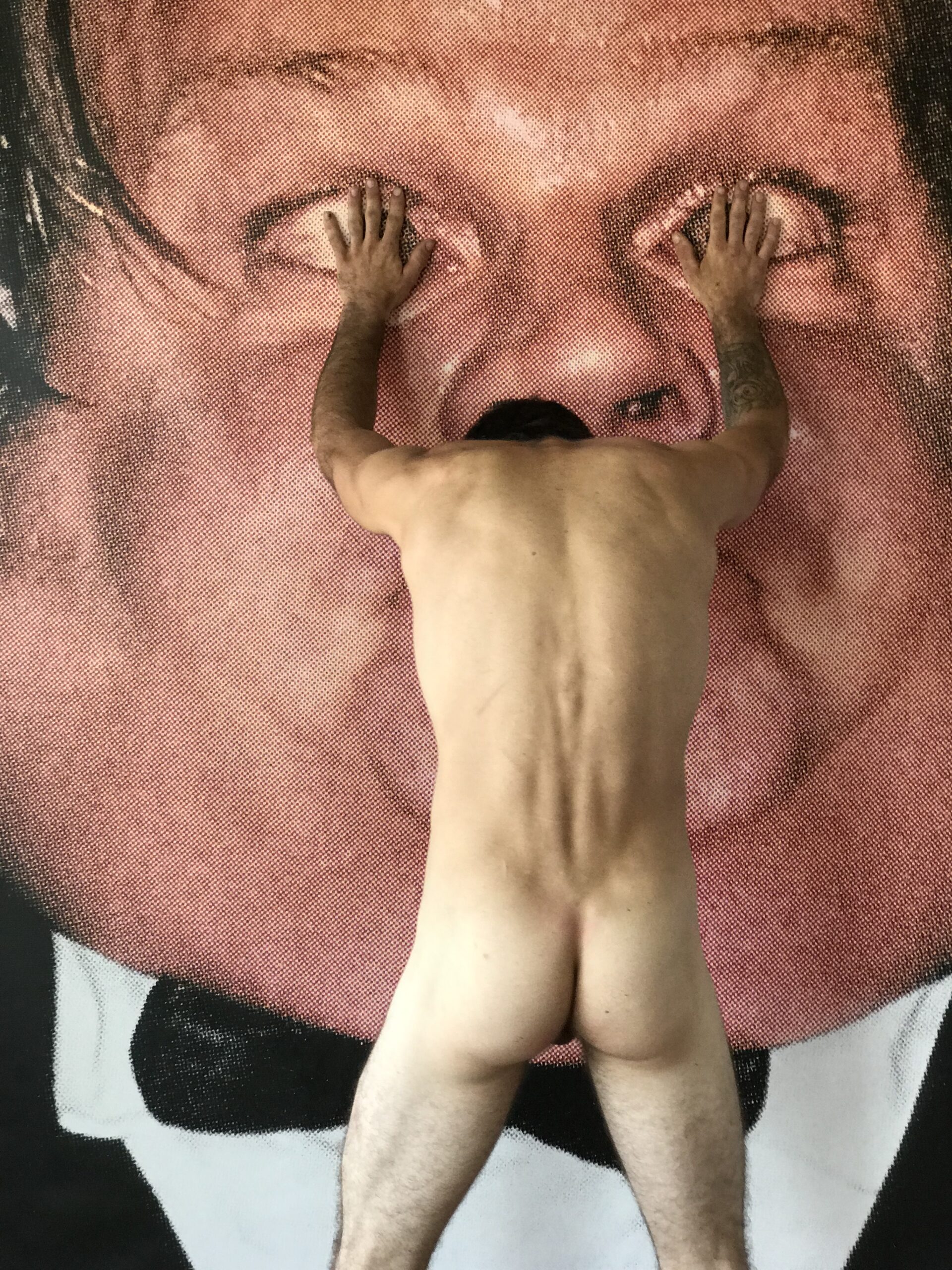

Chivas Clem, Cole in front of Chris Farley, 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Dallas Contemporary.

One image that stands out is the boy sitting on the staircase — there’s an almost haunting innocence in his gaze. What drew you to him in the first place?

That kid is the most sensitive. He’s actually in prison right now. The reason that I met him was because he broke into my house when I was out of town. I came back and I found him in the bathtub asleep, just taking a bath. He has the kind of face that could haunt you for a thousand years.

Do you believe that, in many ways, the men you photograph are shaped by their environments — almost as if they are instruments of their own fate?

God, an instrument of your own fate. I never really thought about that, but you’re exactly right. Those are powerful words. A lot of these men are victims of their circumstances. They grow up without access to anything. I would say 60 to 70% of them are virtually illiterate, and there’s such naivety and innocence to them.

Do you find that this innocence or naivety gives them a different kind of wisdom or perspective?

There’s an interview from the ‘60s with Pasolini, and the interviewer asks, “Who are your favorite people?” And Pasolini’s response implied an admiration for the uneducated because they aren’t spoiled by petty-bourgeois ideals. It’s the same with Jean Genet, who was fascinated by criminals, viewing them as figures of innocence. He said something like, “The criminal organizes a disordered world for us.”

Given the transient and often isolated nature of the men you work with, is there a sense of camaraderie among them?

That’s an interesting question. I would say that most of them are quite feral, like lone wolves, because they were never parented correctly or taught about what it means to be loved. They see relationships as transactional. They might develop a bond with somebody but it’s often fleeting. They might have to go to prison for two years, then that person finds somebody else.

If you’re barely surviving, I think it’s very difficult to create any genuine bonds. I have models that have girlfriends, but the relationships never last. And it’s always transactional. She has a check, a place to stay, or he gets a check and she stays with him. When I first started doing this, one of my models went to prison and I sent him a care package. He called me crying, and this is not somebody who cries. He said that he’d never had someone do something so nice for him in his entire life — that his mother would never. And she probably just can’t afford to.

Photographer Chivas Clem Takes JackPierson Inside His Archive of Drifters

Greg with My Grandfather’s Shotgun, From Behind, 2016. Courtesy of the artist and Dallas Contemporary.

This week, Dallas Contemporary opened Shirttail Kin, a hard left turn from their regular programming. The transgressive exhibition includes 70 portraits by Chivas Clemdocumenting a nomadic community of drifters—generally white and socioeconomically impoverished—he encountered upon returning to his hometown of Paris, Texas. “Most of them are felons and don’t vote and have no relationship to politics,” Clem said of the men featured in his uncompromising images. “They live in a class outside of the lower class.” While they might have seemed like an odd choice of subject for Chivas, a queer, 52-year-old artist whose shown his work in New York and Los Angeles, Dallas Contemporary found the photographs—stark and vulnerable documentations of grit, aimlessness and freedom—particularly fit for exhibition about of the November election. Just before he headed down to Dallas to pin the portraits on the museum’s wall (but not in a Wolfgang Tillmans-y way, as he clarified), Clem jumped on a call with fellow photographer and friend Jack Pierson to talk about the thorny matter of exploitation and the process of immersing himself in a world of “theft and grift.”—EMILY SANDSTROM

———

JACK PIERSON: How are you?

CHIVAS CLEM: I’m okay. I’m kind of nervous about the show, but obviously very excited.

PIERSON: Right.

CLEM: I’m going to Dallas after tomorrow to start installing.

PIERSON: Oh, my goodness. That’s exciting. How did you finally resolve getting them on the wall?

CLEM: We just decided to pin them.

PIERSON: Oh, goodie.

CLEM: Which I think will be fine. I feel like it’s sort of coded as being Wolfgang Tillmans-y. But I don’t think it has to be. I can figure out a way to not do that. Lots of people were doing it before he was.

PIERSON: Oh, really? Name one.

Drifter on my bed, 2018. Courtesy of the artist and Dallas Contemporary.

CLEM: Oh, I don’t know. [Robert] Mapplethorpe, or you, obviously. Is that the answer you were looking for?

PIERSON: Mappethorpe never pinned anything. His frames were the best thing about the work.

CLEM: I know. Anyway, I’m excited about it. It’ll be interesting to see how it’s received in Texas, which has a more conservative audience than say, New York or L.A., where I feel like people were really into it.

PIERSON: So, what ever possessed the institution to do this show? It seems like quite an outrageous choice for them. I mean, even you must agree?

CLEM: No, absolutely. It did seem outrageous. I think Alison [Gingeras] is a provocateur, and she thought that it would be an interesting choice with the election coming up. I had talked to her about how in the beginning of this project, I was creating an archive of images of rednecks and deplorables, and I was trying to think about what a deplorable looked like and what white male rage looked like.

PIERSON: Did you get away with saying that? Deplorables? Didn’t even Hilary Clinton get in trouble?

CLEM: Well, I’m quoting. It’s not my word. Mostly I had spoken about them as rednecks, but really the project was about these lower-class white men who were full of rage, that had trucks and Confederate flags and were characterized by their racism, their transphobia, et cetera.

PIERSON: Is that the basic profile of most of your models? They all seem somehow so sensitive to me. Or is that your skill as a photographer?

CLEM: I think that’s my skill as a photographer.

PIERSON: I had the impression that a lot of them were friends of yours, or that you made friends with them. Are they actual Trump supporters?

CLEM: Well, yeah. But I would imagine they’re totally disengaged from politics.

PIERSON: That’s what I was going to say. Do they even have an opinion?

CLEM: No-

PIERSON: They don’t have trucks. They don’t have Confederate flags. They don’t have anything. No?

CLEM: They don’t have anything. But they’re born of that culture, right? Most of them are felons and don’t vote and have no relationship to politics. They live in a class outside of the lower class. They’re drifters. Some of them are sort of hobo-like. When I come back, I am surrounded by that. I knew some from my neighborhood, and they would come to the studio, and they were terrible helping me out. So, I’d be like, “Why don’t you just lay around and take off your clothes and smoke and let me take your picture?” That’s how I started. I asked them to hang around the house, and they would take a bath or they’d take a nap or they’d eat a banana and I’d take a picture.

PIERSON: Perhaps we should say the name of your town.

CLEM: Paris, Texas.

PIERSON: Fantastic. So loaded.

Coty in Abandoned House, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Dallas Contemporary.

CLEM: Yeah.

PIERSON: I’m completely simpatico with what you’re doing. But imagine yourself in front of the graduate department of photography at Yale, Columbia, any high-class art school. How are you going to defend it to a Gen Z kid or, worse, a millennial, who sees what you’re doing as exploitative? I know from teaching the kids a lot of these days that they don’t feel like they have a right to photograph outside their own cultural background.

CLEM: Yeah.

PIERSON: So how are you anything but a privileged person preying on the financial needs of drifters and hobos?

CLEM: Well, I decided that if I approached the work with integrity and a real, authentic desire to capture them, I didn’t feel like I was overstepping any moral boundaries. I never felt like I was exploiting them. They enjoyed being seen, and that was almost part of the work. It’s like I was working in concert with them.

PIERSON: I see that fully in the imagery.

CLEM: I think that unnecessarily hurts artists when it puts you into a box like that, where if somebody comes from a middle-class background, then somehow they’re not supposed to engage with people that are socioeconomically more impoverished or something. I don’t think you can get anywhere with that, and I couldn’t have made this work in those kinds of environments. Maybe because I was outside of the academy, outside of the art world, that’s what allowed me to do this.

PIERSON: Right, if you lived in New York City–

CLEM: Exactly. When I was a kid, these were the people that I was terrified of, that tortured me and there was something about reaching out to them. I felt like they’re outsiders now in a way that I’m an outsider. I didn’t feel above them, I felt a kinship with them. That’s why the show is called Shirttail Kin. I developed this enormous fondness and tenderness for all of these guys, despite us coming from very different backgrounds, but also being white men in the south. There’s an honesty to the work that supersedes that kind of thing.

Cole in Blossom, night, 2020. Courtesy of the artist and Dallas Contemporary.

PIERSON: I’d agree with you, but it’s a question worth asking, because I’ve heard it time and time again.

CLEM: Sure.

PIERSON: I think it’s ridiculous, but I’m also an old white guy.

CLEM: I think I’ll get plenty of blow-back about that. It’s a legitimate question. In some ways, I started the project very naively, and that never really occurred to me until recently when I started showing the work to people and doing studio visits. People slowly started asking those kinds of questions.

PIERSON: Well, the other funny thing is, if you were an actual pornographer with a Las Vegas studio and you were paying white guys to perform, I don’t think that question would come up. It’s just like, “Well, it’s porno.” It comes up now because you are positioning it in a museum or a public institution.

Cole in front of Chris Farley, 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Dallas Contemporary.

CLEM

It’s true. I don’t know what happened in the art world in the past, say, 15 years, but art more and more is reflected in our pop culture as this kind of propaganda for white neoliberal utopians. Does that make sense?

PIERSON: Yeah.

CLEM: An interviewer asked me the other day, “Aside from hope and compassion, what did you bring to your models?” And I’m like, “I didn’t bring hope…”

PIERSON: $50.

CLEM: Exactly. I paid them for working for me. Of course, I ended up becoming very close to them, but I didn’t rescue them from poverty or something. People want to see the work as me sort of reaching out, but that’s not what it’s about. Did you ever see that interview with [Pier Paolo] Pasolini? He’s talking about—I can’t remember the Italian term for it—but it’s similar to peasant. It’s somebody who has not been touched by bourgeois values like materialism. He said that he always felt very close to young people who were naive to bourgeoisie values. That’s something about my models, too. Despite the fact that they’ve had rough lives, there’s a certain freedom in that.

PIERSON: Yeah. I think the only other place you get that essence is from the super rich.

CLEM: Yes.

Dillon at the carwash, Night, 2020. Courtesy of the artist and Dallas Contemporary.

PIERSON: I’ve always maintained that the super rich are exactly the same as the super poor.

CLEM: That’s exactly what he talks about in the interview, and that what he most despises is the middle. And because these guys have never been touched by the middle, there’s this beautiful naiveté and this real poignant innocence to them, which I hope to have captured.

PIERSON: I’m also thinking of David Hurles, whose work you must know. He was a ’70s pornographer from central Los Angeles who was focused on a certain kind of very rough individual. He just considered robbery and violence part of the game.

CLEM: It’s part of your resume.

PIERSON: Or part of the expenses. You’re going to get stolen from a certain amount and beat up a certain amount.

CLEM: Yeah.

PIERSON: Have you encountered that yet?

CLEM: Absolutely. My boyfriend found a needle in my car, but I just consider that part of it. I’ve only ever had one model who was an actual sociopath and threatened me once, but he came back the next day and apologized. Most of them have been very gentle. But what I learned was that everything is transactional, despite however many tender feelings I had toward them. It kind of hurt my feelings in a lot of ways, but I had to get used to it. Theft and grift are all a part of the project.

Coty in the Bathtub after Breaking In, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Dallas Contemporary.

PIERSON: Interesting. I mean, that’s a lot.

CLEM: It has been a lot. When I started doing it, I really didn’t intend to use the photos. I started by filming them, and I made this piece where I had different guys reading Sylvia Plath’s Daddy. So, all the pictures were studies, and then I was putting them on Instagram, and Peter McGough called me out of the blue one day and said, “These are great. You should show these.” He’s like, “You’d be crazy not to show these.” And I was like, “I don’t know. I’m not really a photographer, per se.” And he was like, “That doesn’t matter. They’re great. You should show them.”

PIERSON: That’s fantastic.

CLEM: Jessica Craig-Martin was another person that was like, “You should do something with them.”

PIERSON: Your first show was at Bortolami?

CLEM: With this work?

PIERSON: Yeah.

CLEM: Yes. I was in a group show in L.A. at Tony Payne, and then I did a show with Bill Arning.

PIERSON: Which was in Houston.

CLEM: Yes, before he had his space upstate.

PIERSON: And since then, have there been any shows of this work?

CLEM: No, there haven’t.

PIERSON: So, that’s a couple years ago now, right?

CLEM: Yeah, it was a couple of years ago. People really like the work, but male nudes are hard sell.

PIERSON: As I well know.

CLEM: As you well know. When I went to L.A., I did studio visits with some very good galleries, some really smart people, and they were all like, “We love this, but there’s no way we can sell it.” And I think at this particular moment, galleries really need to sell things. Galleries can’t afford to show things that don’t move. So, I don’t have a gallery. I have a small gallery in Dallas, but she doesn’t even really like the work and–

PIERSON: [Laughs]

CLEM: No, I’m serious.

PIERSON: I believe you.

CLEM: Occasionally, I’ll sell something here or there to somebody, but I don’t have a gallery.

PIERSON: You might have to explore alternative spaces.

Jer eating catfish with dirty fingers, 2023. Courtesy of the artist and Dallas Contemporary.

CLEM: Yes.

PIERSON: Like places where Bruce LaBruce or Genesis P-Orridge would show. In every city there’s some pocket of renegade.

CLEM: It’s true.

PIERSON: I do think the work should be known in a broader way.

CLEM: I mean, I’d like to show it and sell it and maybe it can enter the marketplace at some point. I mean, years ago, they said Mapplethorpe would never ever be able to sell. Of course, he made all of those orchids and things that sold really well, but I guess they didn’t show those in the beginning, did they?

PIERSON: I think they showed them, but with plenty of the other stuff that could sell.

CLEM: Yeah.

PIERSON: You’ve got pretty trees behind you. Every once in a while you throw in a landscape or something.

Chris Smoking Outside, 2023. Courtesy of the artist and Dallas Contemporary.

CLEM: Yeah. There’s other things, there’s landscapes and sometimes a flower. But they mostly wanted the portraits and the nudes, so that’s what the show mostly consists of.

PIERSON: That’s cool. Well, you’ve got a great golden opportunity here to show the work without having to have it be commercial.

CLEM: Yeah, and there’s a catalog, which is incredible. Hilton Als wrote the essay.

PIERSON: That is incredible.

CLEM: I mean, who could ask for more? It’s like the best thing that ever happened, really. And now I’m going to be in Interview Magazine. It’s like, I’ve arrived.

PIERSON: Well, congratulations.

CLEM: And I’m only 78! Thank you.

PIERSON: You’re not. How old are you?

CLEM: I’m 52.

PIERSON: One year for every state in the union. Well, I wish you the best.