Pre-Columbian Peruvian Burial Textiles

Collection of Peruvian Burial Textiles, approx. 1100 – 1400 A.D., belonging to the Culture (verbal estimate by textile expert). All seem to be cotton, except for the textile with “dark burn” markings, which was explained to me, is from bodily fluids (hence the body was not properly prepared for proper burial). That one is Alpaca, not cotton.

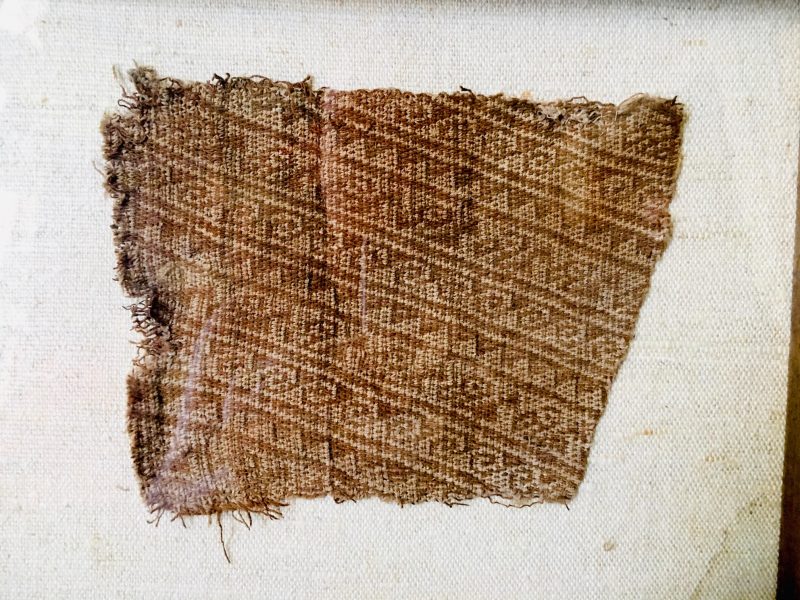

1. Peruvian Burial Shroud – A (large) / $475

Originates from: South America

Era: Between 12th and 14th Century

Dimensions: 11” H x 19” W

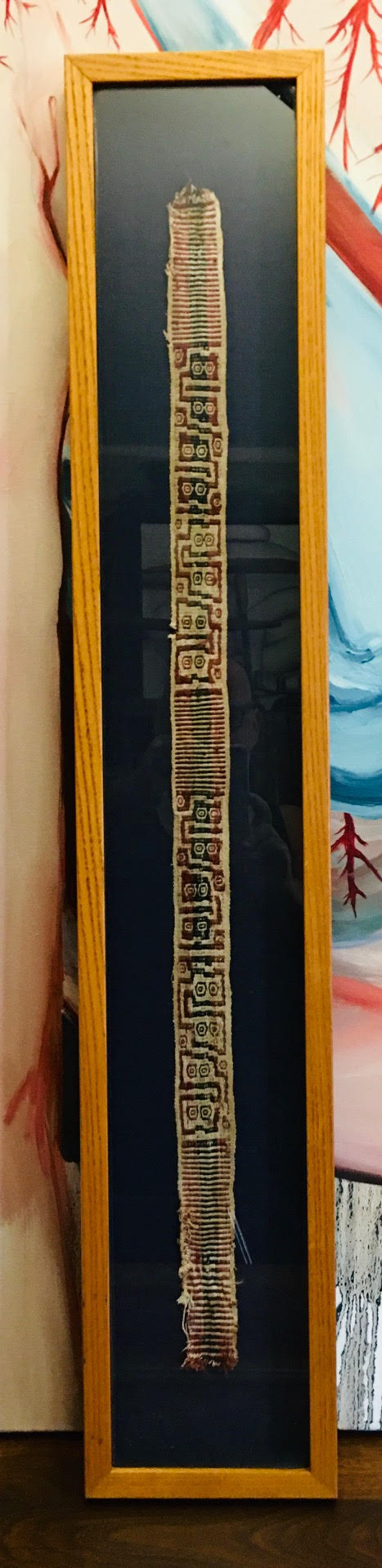

2. Peruvian Burial Shroud – B (vertical) / SOLD.

Originates from: South America

Era: Between 12th and 14th Century

Dimensions: 12” H x 7” W

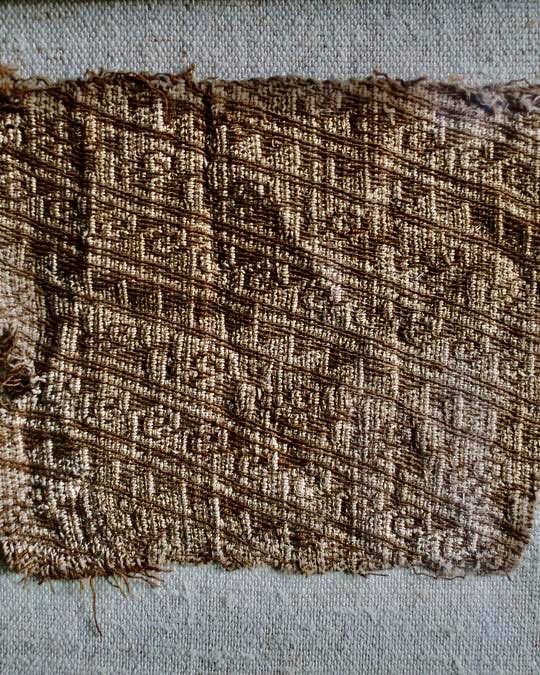

3. Peruvian Burial Shroud – C / (smaller) $345

Originates from: South America

Era: Between 12th and 14th Century

Dimensions: 8” H x 10” W

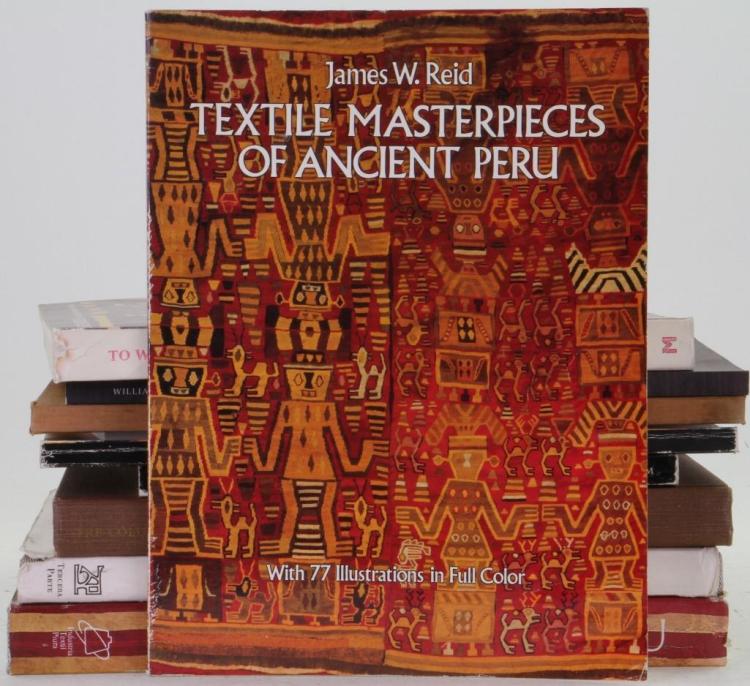

The art of the Inca civilization of Peru (c. 1425-1532 CE) produced some of the finest works ever crafted in the ancient Americas. Inca art is best seen in highly polished metalwork, ceramics, and, above all, textiles, with the last being considered the most prestigious by the Incas themselves. Designs often use geometrical shapes, are standardized, and technically accomplished. The European invaders destroyed much of Inca art either for sheer monetary gain or religious reasons but enough examples survive as testimony to the magnificent range and skills of Inca artists.

Influences & Designs

Although influenced by the art and techniques of the earlier Chimu civilization, the Incas did create their own distinctive style which was an instantly recognisable symbol of imperial dominance across their massive empire. The Incas would go on to produce textiles, ceramics, and metal sculpture technically superior to any previous Andean culture, and this despite stiff competition from such masters of metalwork as the craftsmen of the Moche civilization.

Just as the Incas imposed a political dominance over their conquered subjects, so too with art, they imposed standard Inca forms and designs. The art itself did not suffer as a consequence, though. As art historian Rebecca Stone puts it,

Standardisation, though powerfully unifying, did not necessarily lower the quality of art; technically Inca tapestry, large-scale ceramic vessels, mortar-less masonry, and miniature metal sculptures are unsurpassed. (Art of the Andes, 194)

The checkerboard stands out as a very popular design. One of the reasons for the repetition of designs was that pottery and textiles were often produced for the state as a tax, and so artworks were representative of specific communities and their cultural heritage. Just as today coins and stamps reflect a nation’s history, so too, Andean artwork offered recognisable motifs which either represented the specific communities making them or the imposed designs of the ruling Inca class ordering them. The Incas did, though, allow local traditions to maintain their preferred colours and proportions. In addition, gifted artists such as those from Chan Chan or the Titicaca area and women particularly skilled at weaving were brought to Cuzco so that they could produce beautiful things for the Inca rulers.

It is also notable that both Inca pottery decoration and textiles did not include representations of themselves, their rituals, their military conquests, or such common Andean images as monsters and half-human, half-animal figures. Rather, the Incas almost always preferred colourful geometrical designs and abstract motifs representing animals and birds.

Textiles

Although very few examples of Inca textiles survive from the heartland of the empire, we do have, thanks to the dryness of the Andean environment, many textile examples from the highlands and mountain burial sites. In addition, Spanish chroniclers often made drawings of textile designs and clothing so that we have a reasonable picture of the varieties in use. Consequently, we have many more examples of textiles than other crafts such as ceramics and metalwork.

For the Incas, finely worked and highly decorative textiles came to symbolize both wealth and status. Fine cloth could be used as both a tax and currency, and the very best textiles became amongst the most prized of all possessions, even more precious than gold or silver. Inca weavers were technically the most accomplished the Americas had ever seen and, with up to 120 wefts per centimetre, the best fabrics were considered the most precious gifts of all. As a result, when the Spanish arrived in the early 16th century CE, it was textiles and not metal goods which were given in welcome to these visitors from another world.

It seems that both men and women created textiles, but it was a skill women of all classes were expected to be accomplished at. At the capital Cuzco, the finest cloth was made by male specialists known as qumpicamayocs or ‘keepers of the fine cloth’. The principal equipment was the backstrap loom for smaller pieces and either the horizontal single-heddle loom or vertical loom with four poles for larger pieces. Spinning was done with a drop spindle, typically in ceramic or wood. Inca textiles were made using cotton (especially on the coast and in the eastern lowlands) or llama, alpaca, and vicuña wool (more common in the highlands) which can be exceptionally fine. Goods made using the super-soft vicuña wool were restricted and only the Inca ruler could own vicuña herds. Rougher textiles were also made using maguey fibres.

Besides using dyed strands to weave patterns, other techniques included embroidery, tapestry, mixing different layers of cloth, and painting – either by hand or using wooden stamps. The Incas favoured abstract geometric designs, especially checkerboard motifs, which repeated patterns (tocapus) across the surface of the cloth. Certain patterns may also have been ideograms. Non-geometrical subjects, often rendered in abstract form, included felines (especially jaguars and pumas), llamas, snakes, birds, sea creatures, and plants. Clothes were simply patterned, commonly with square designs at the waist and fringes and a triangle marking the neck. One such design was the standard military tunic which consisted of a black and white checkerboard design with an inverted red triangle at the neck.

Additional decoration could be added to textile articles in the form of tassels, brocade, feathers, and beads of precious metal or shell. Precious metal threads could also be woven into the cloth itself. As feathers were usually from rare tropical birds and condors, these garments were reserved for the royal family and nobility.

Conclusion

The European invaders in the 16th century CE not only ruthlessly melted down or spirited away any precious Inca goods they found but also attempted to repress elements of Inca art, even banning such trivial objects as the qeros beakers in an attempt to curb drinking habits. Distinctive Inca textile designs such as those connected to royal power were also discouraged but, in defiance, many of the indigenous peoples continued with their artistic traditions. Thanks to this perseverance and continuity, and despite an evolution where designs were blended with elements of colonial art, many traditional Inca designs and motifs survive to this day and are celebrated as such in the ceramics, metalwork, and textiles of modern Peru.

Research:

https://www.ancient.eu/Inca_Art/

https://www.imj.org.il/en/exhibitions/new-collection-2

https://www.imj.org.il/en/events/2500-years-siguas-wari-chancay-and-inca-textiles

http://www.historyshistories.com/inca-religion-activity.html

https://rugrabbit.com/node/187900

https://rugrabbit.com/profile/440

https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-andean-textiles-provide-clues-complex-ancient-culture