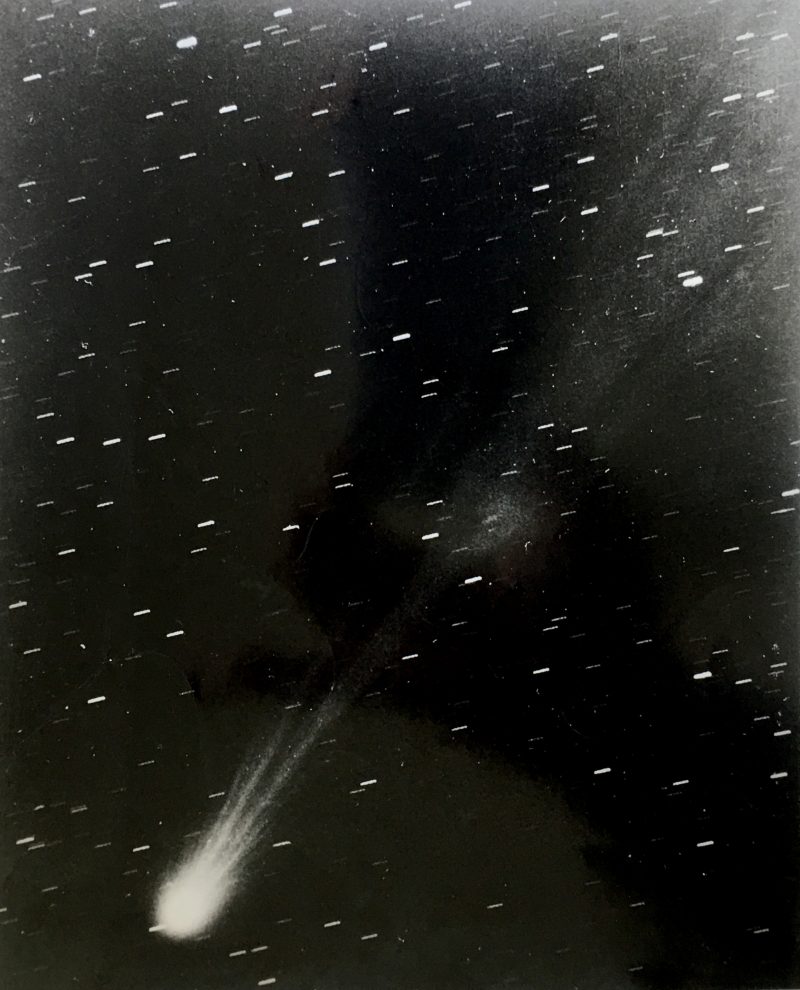

SOLD. Rare Vintage Authentic Photograph ‘Swift’s Comet 1892’

Rare Authentic Vintage Photograph of “Swift’s Comet 1892” taken at Sydney Observatory, printed in darkroom (not digital) as part of as collection of mid century works found in a private collection. Measures 8 x 10 inches. Excellent condition.

I acquired this from the son of a private collector in Los Angeles, who’s father died in 1999 & left him hundreds of mid century artworks. A fascinating collection.

Asking $225.

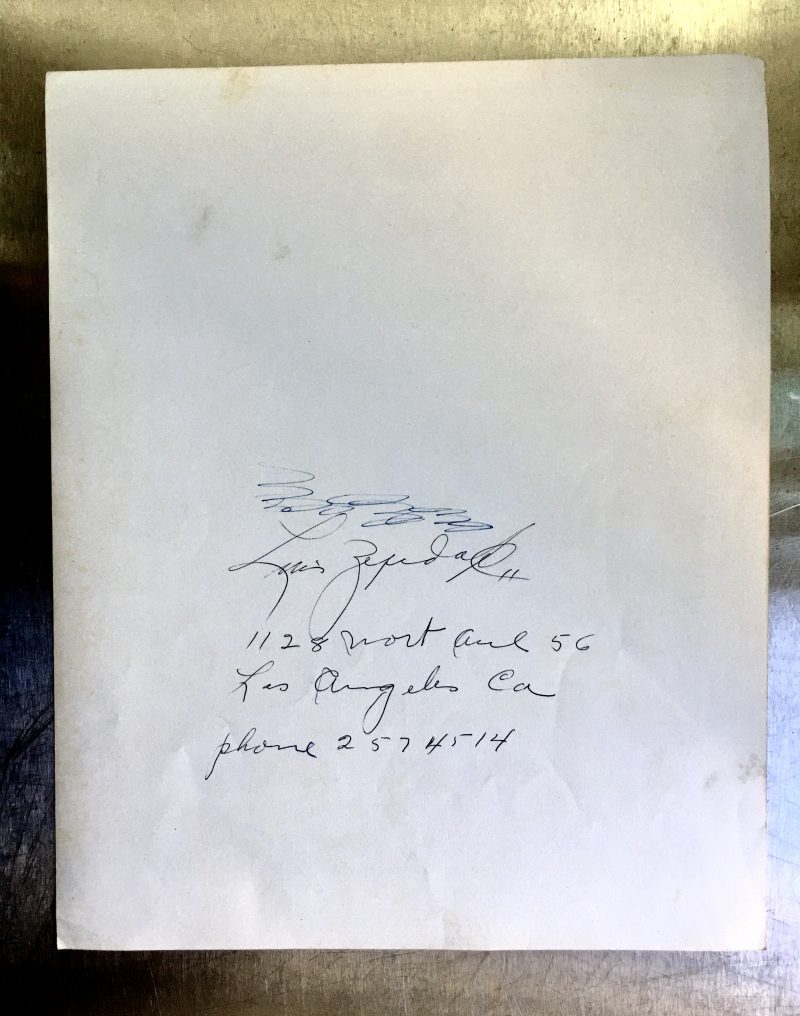

Verso has hand written the name of the art dealer and his address in Los Angeles.

19th century photograph of Comet Swift A, 1892. The comet moves on an extremely elongated elliptical orbit around the sun with an estimated orbit of about 13, 600 years.

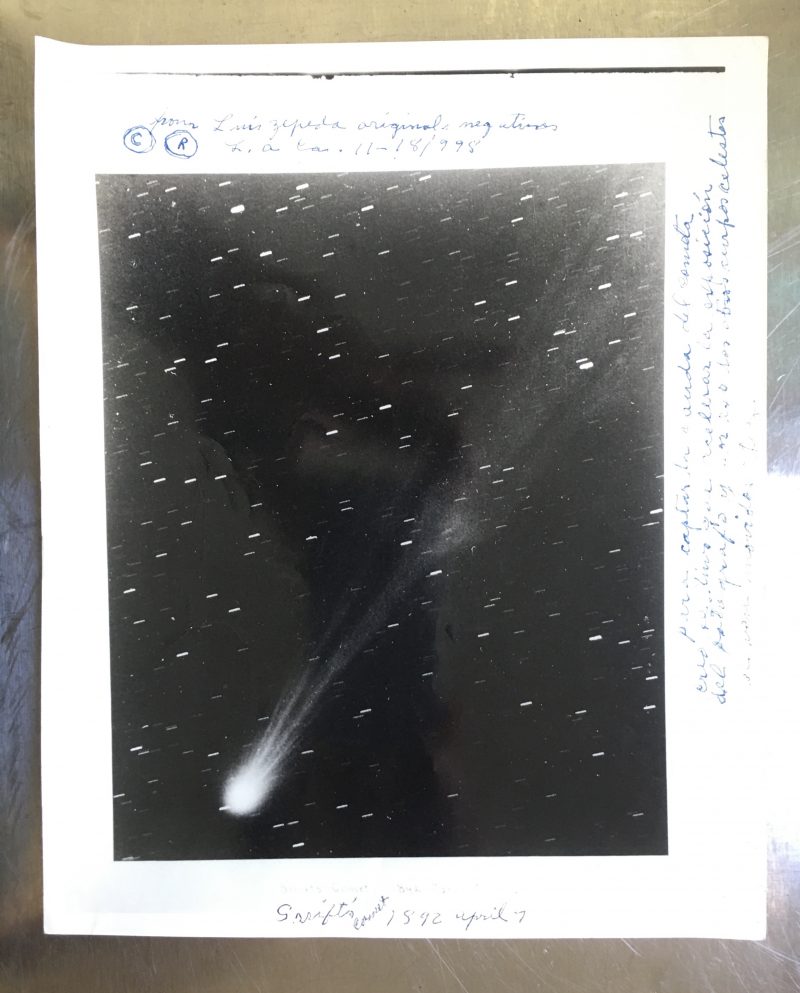

Hand written notes by the art dealer/collector say the following: “Swift’s Comet 1892 April 7”.

“From Luis Zepeda original negatives, L. A. Ca (I presume; Los Angeles California), 11-18.998”

“(In Spanish / needs to be translated) …”

An Early Photo from Sydney Observatory of Comet Swift 1892

February 28, 2013

By Nick Lomb

A drawing of Comet Swift 1892 based on a photograph taken at Sydney Observatory on the early morning of 22 March 1892. The drawing is by Richard Pickering Sellors while the original photograph was taken by James Short. Courtesy Powerhouse Museum

Henry Chamberlain Russell, the Government Astronomer at Sydney Observatory, received a telegram indicating the discovery of a new comet on 9 March 1892. The discoverer was 72-year old Dr Lewis Swift of the Warner Observatory at Rochester, New York State, who had nine previous comet discoveries to his credit. This new comet was to become famous because of the rapidly changing appearance of its tail. Photographs taken in early April by two well-known American astronomers EE Barnard of Lick Observatory and WH Pickering of Mt Wilson Observatory, but observing from Peru, are usually credited with showing the phenomenon. However, Russell had both photographed and documented it earlier.

Clouds did not permit observations of the comet until the morning of 11 March when a 1 hour 50 minute exposure was made of the comet with the ‘star camera’. In his report to the Royal Astronomical Society in London Russell says that as the photograph was taken through thin cloud and bright moonlight (the waxing gibbous moon was two days from full) the comet’s tail appears fairly faint. Still five ‘equidistant rays’ could be seen spread over an arc of 25°.

The next opportunity to see the comet was 11 days later, on the morning of 22 March, when the Observatory’s photographer James Short took an exposure of 2 hours 23 minutes though with clouds intervening for almost half an hour. This time the photograph shows eight separate rays in the tail, while according to Russell one of the original rays has now detached itself from the head of the comet and is not ‘visibly joined to it’. As on the previous occasion, the tail could not be seen through the 11½-inch telescope (still used in the south dome of the Observatory, but now called the 29-cm telescope) except as ‘a slight hazy extension’.

To accompany his report to the Royal Astronomical Society, Russell had one of his staff, Richard Sellors, make an enlarged drawing of the original negative. Sellors could easily do this as the photograph had the standard grid or reseau that was used with the Observatory’s major star cataloguing project, the Astrographic Catalogue.

Swift’s Comet photographed on 4 April 1892 (top) and 6 April 1892 (bottom) by Professor EE Barnard. The images are on Plate IV in A Popular History of Astronomy in the nineteenth century by Agnes M Clerke (third edition). Courtesy archives.org

Agnes Clerke in her Popular History of Astronomy in the nineteenth centurysays that Swift’s 1892 comet was the brightest comet that people in the northern hemisphere had seen for ten years. It was brightest about the time of its closest approach to the Sun on April 6. Then the head of the comet was of third magnitude (same as the predicted brightness of Comet PANSTARRS in March 2013).

In describing the tail of the comet Clerke refers to the photographs by EE Barnard and WH Pickering, claiming that they ‘marked a noteworthy advance in cometary photography’. The description based on that of Barnard is rather flowery: ‘The middle portion of the tail is brighter and looks like crumpled silk in places’. And ‘The next morning the southern was the prominent branch…with a strange excrescence, suggesting the budding-out of a fresh comet in that incongruous situation’.

Despite the flowery descriptions from the American Barnard, I cannot feeling that if Henry Chamberlain Russell had not been in distant, far-away Australia, then the photographs of Comet Swift taken under his direction would be the ones that would be the best known.

MORE RESEARCH:

Photographic print of Comet Swift taken at Sydney Observatory

Twelve years later, on March the seventh, a comet was discovered by L. Swift at the Warner Observatory in Rochester, New York. The news was cabled, on the ninth of March, to John Tebbutt in Australia, who two days later located the comet. From March 11th to May 2 Tebbutt made a series of filar micrometer measurements as he watched the comet pass across the sky.

It was also during this period that staff at Sydney Observatory took the opportunity to photograph the comet. The images were most likely to have been taken by James Short, under H.C. Russell’s instruction, using the newly acquired astrograph or ‘Star Camera’. For more information on Sydney Observatory’s Star camera see the associated Powerhouse Museum narratitve ‘Sydney Observatory Star Camera & the Mapping the Stars Project’.

Geoff Barker, Curatorial, October 2008

References

Hall, A. and Brooks W. R., ‘Swift’s Comet’, Science, Vol. 1, No. 23, American Association for the Advancement of Science, Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2900301, December 4, 1880

Tebbutt, John, ‘Results of Observations of Wolf’s Comet (II), 1891, Swift’s Comet (I), 1892, and Winnecke’s Periodical Comet, 1892, at Windsor, New South Wales’, Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales for 1892, volume XXVI, Kegan, Paul, Trench, Trubner and Co., London, 1892

W. C. W., ‘Swift’s Comet’, Science, Vol. 1, No. 21, American Association for the Advancement of Science, Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2900114, Nov. 20, 1880