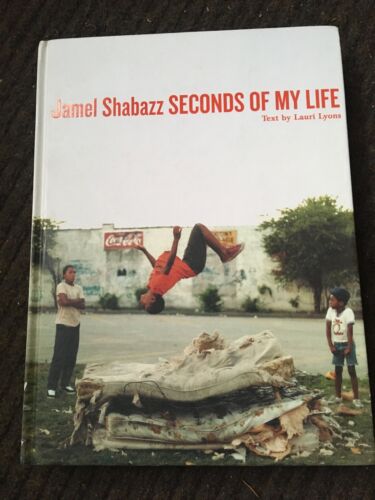

SOLD. ‘Seconds of My Life’ Jamel Shabazz, 2007

‘Seconds of My Life’ Book of Photography.

- Publisher: powerHouse Books (July 1, 2007)

- Length: 256 pages

SOLD.

USD$150

About The Book

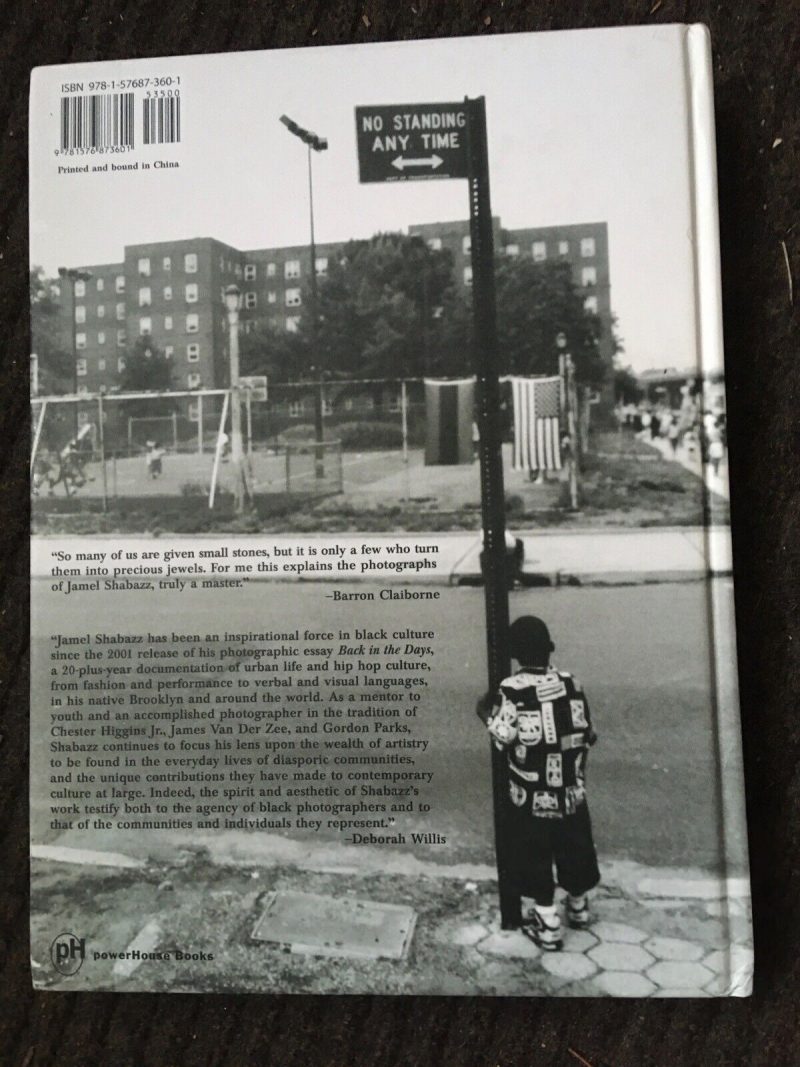

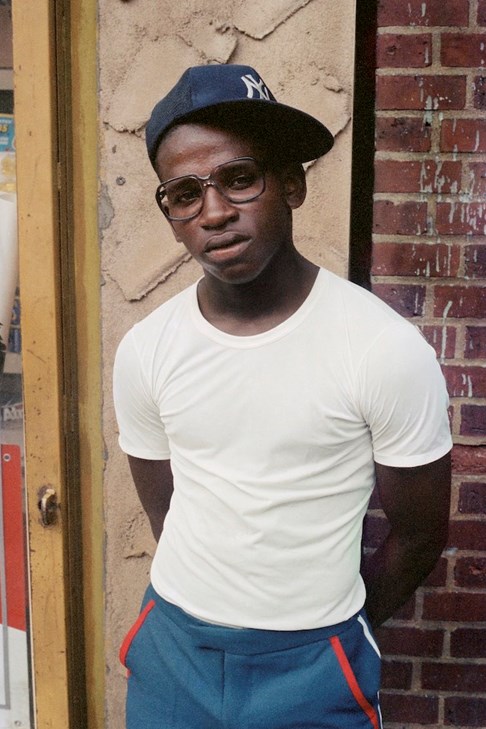

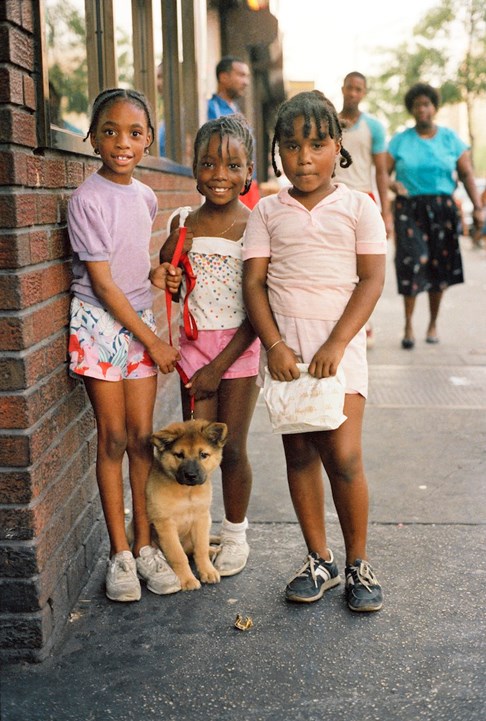

Photography has given Shabazz a sense of purpose, allowing him to connect with the people he encounters on a daily basis. By connecting with his subjects, complimenting their style, and recognizing their potential-and then in turn publishing these images for the world at large to celebrate-in a small but meaningful way Shabazz has been able to counteract the damage society can wreak on self-esteem.

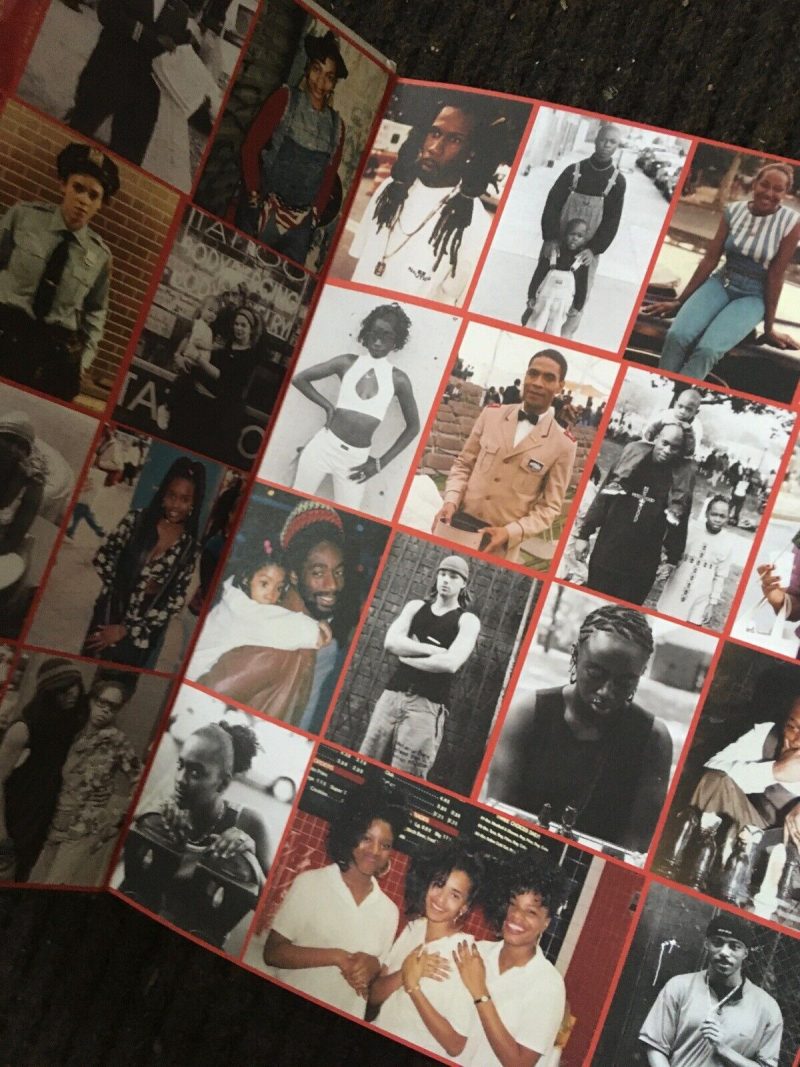

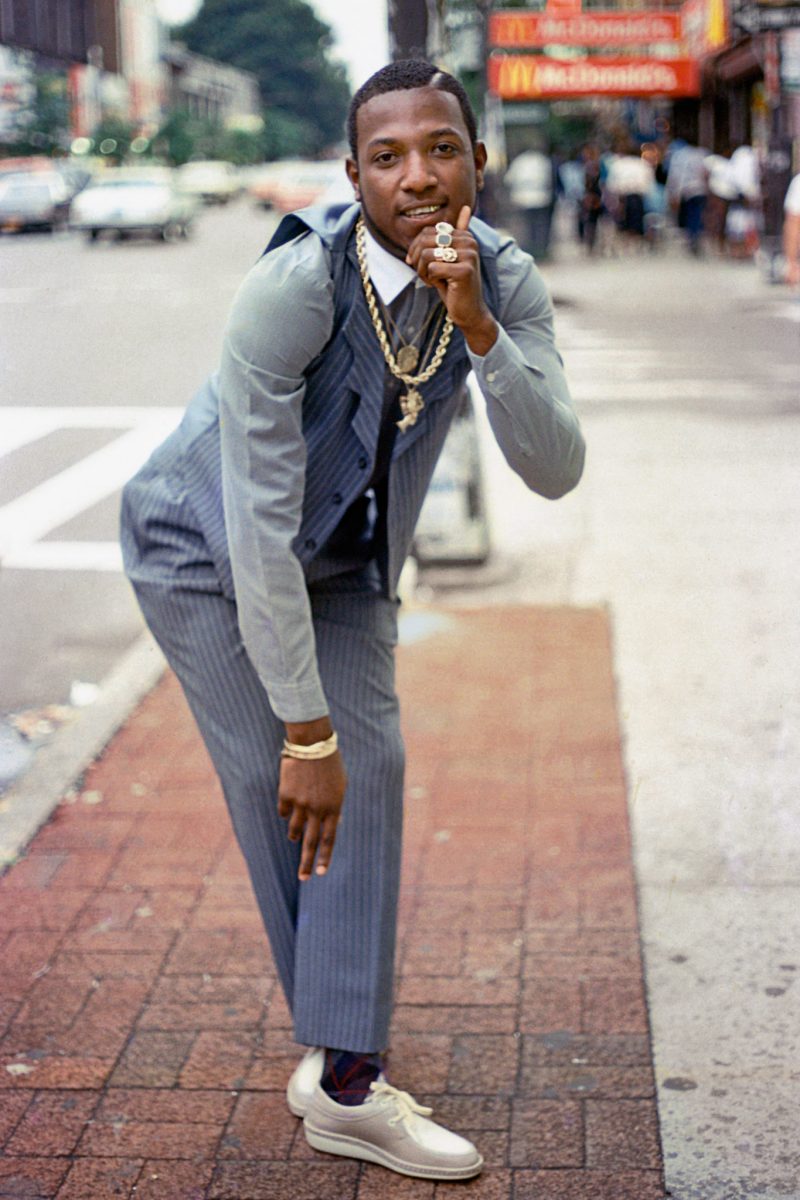

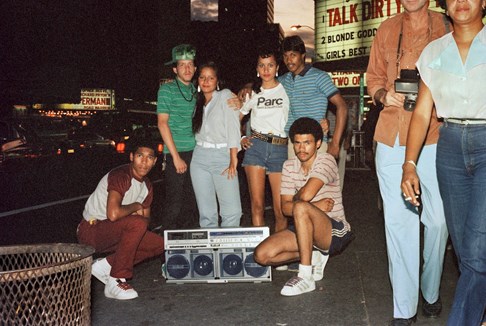

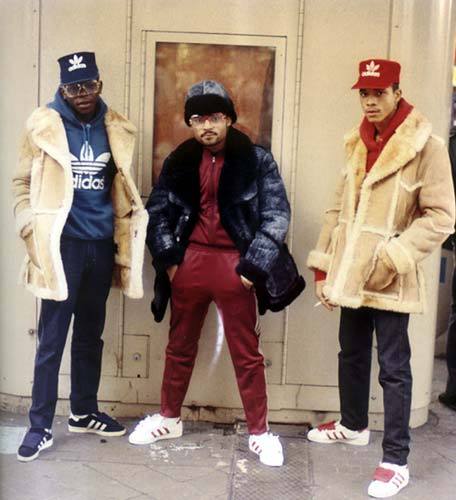

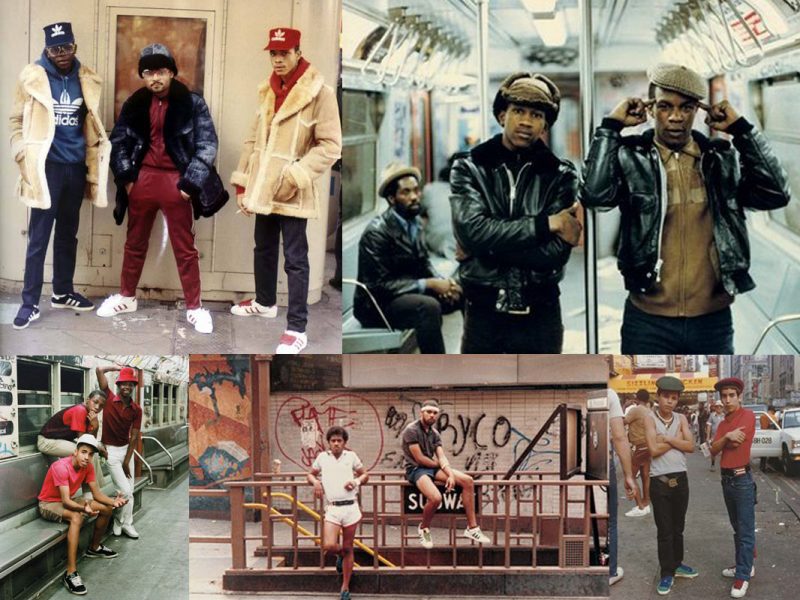

Seconds of My Life, Shabazz’s fourth powerHouse book, delves deeply into the artist’s archives, going back over 25 years and spanning the globe in its representation of human life. Whether in the hills of Jamaica or the shantytowns of Brazil, among the immigrants of France or the Buddhist monks of Bangkok, Shabazz seeks out strong personalities from all races, ethnicities, nationalities, genders, sexualities, and class backgrounds. Shabazz appreciates the poise and confidence of people in all their luminous variety.

Featuring photographs of Dave Chappelle, GrandMaster Flash, The Roots, Sweet Back, Big Daddy Kane, Public Enemy, Kanye West, Common, Mos Def, Russell Simmons, Jill Scott, Roy Ayers, Pete Rock, Jacob the Jeweler, and Grover Washington, Jr., famed fraternities Alpha Kappa Alpha, Kappa Alpha Psi, Delta Sigma Theta, and Zeta Phi Beta, members of the Nation of Islam, Freemasons, Shriners, Bloods, Crips, cops, and city workers, as well as parades and anti-war protests, Seconds of My Life is an unstoppable tour de force.

Lauri Lyons has worked as a photo editor for Magnum Photos, The Source, B.E.T, and Essence, and created photo essays that have been featured in Fortune, Vibe, The Fader, and The London Observer, among others. Lyons’ work has been exhibited in the International Center of Photography, Brooklyn Museum of Art, and the Birmingham Civil Rights Museum, and her first monograph, Flag: An American Story (Vision On Publishing), was published in 2001.

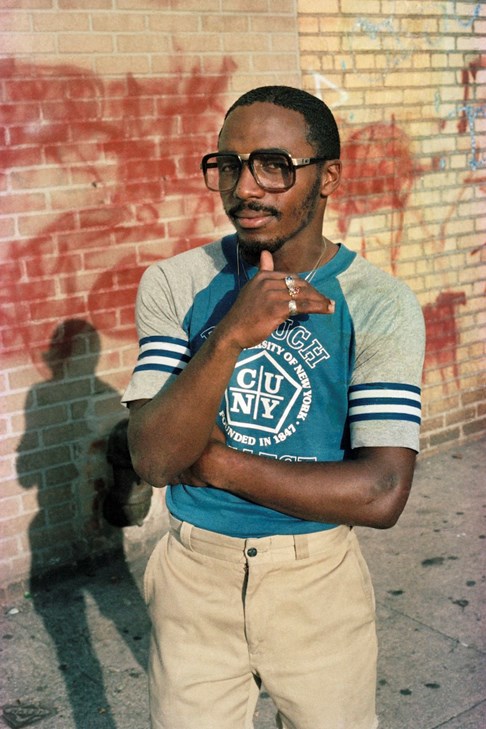

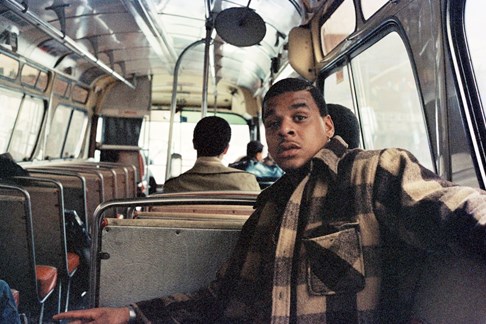

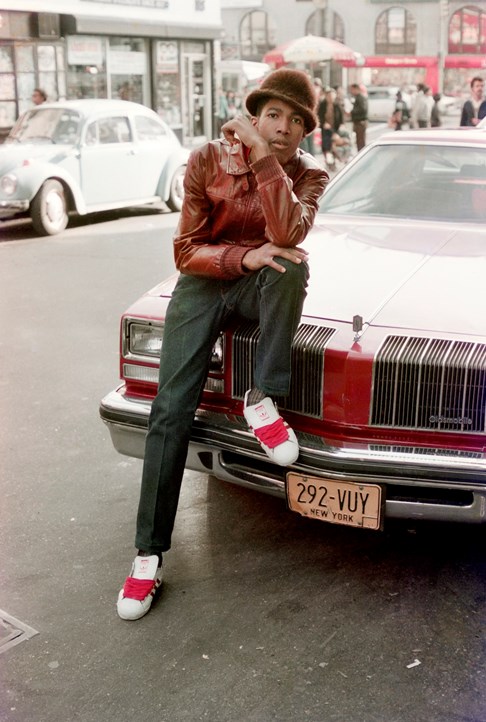

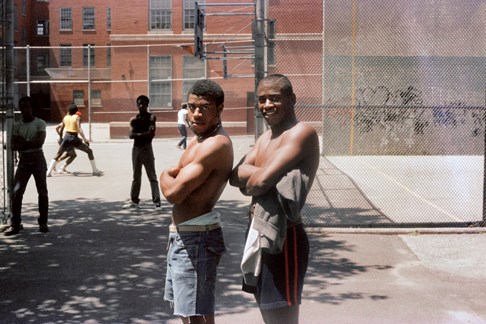

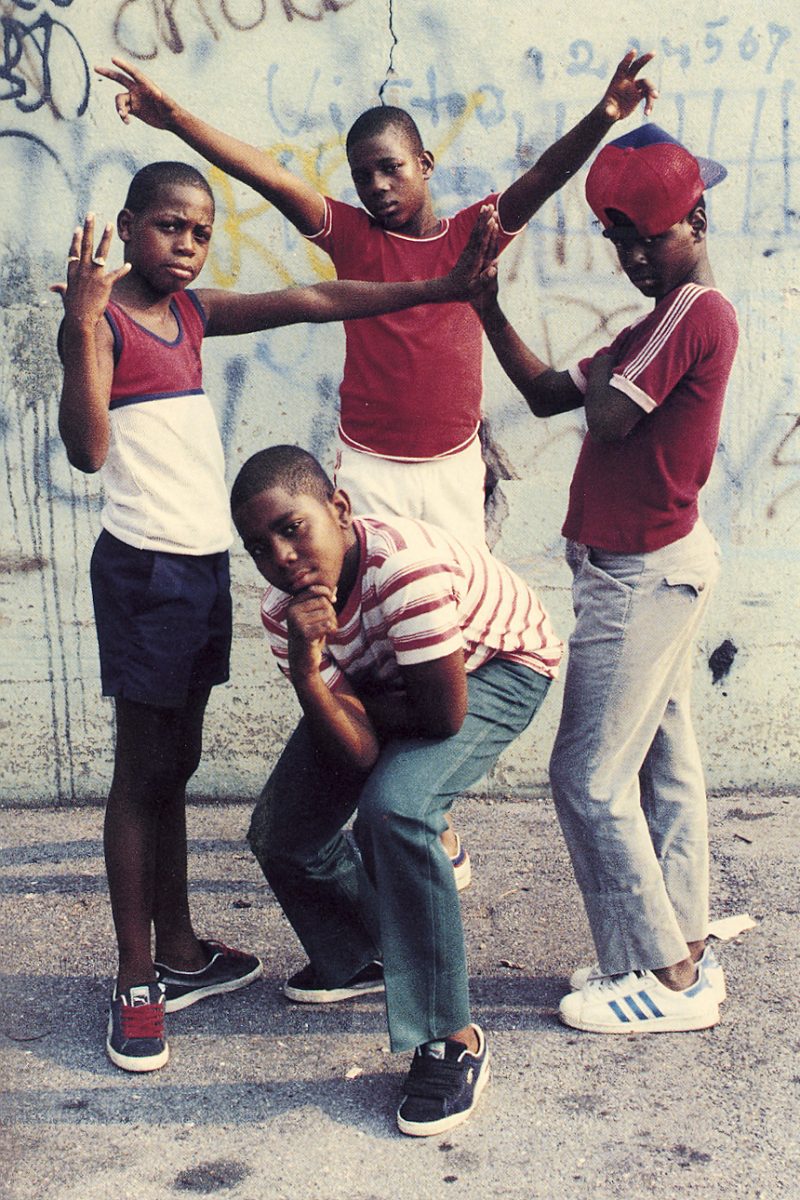

Jamel Shabazz, Rude Boy, East Flatbush, Brooklyn, 1982

New York is a ghost town. The COVID-19 pandemic has brought the metropolis to a standstill. Many are scared to even leave their apartments to buy groceries. The globe-trotting photographer Jamel Shabazz is tucked away in his Long Island home, his “sanctuary.” Shabazz’s world is rocked daily by yet another phone call announcing the death of a loved one. It is a calendar of loss with which he is intimately familiar. He survived the 1980s crack era and the AIDS crisis, when so many friends from his Brooklyn neighborhoods—Red Hook and then East Flatbush—did not.

Every morning, while living under quarantine, Shabazz saunters into one of the several closets in his home and picks up a heavy archive box. Hundreds of identical boxes line every available space in his home. They are organized chronologically and then subdivided by type: black and white, color, medium format, and so forth. One box, just like the others, holds bits of time frozen on negatives, slides, and photographic prints. It is an archive so vast (which even contains the negatives belonging to his father, who was also a photographer) that when asked about the quantity, Shabazz replies, “I just can’t give a count.” He carries the box into the center of his work-space floor. This is a new routine that has become the only consistent thing in uncertain times. Shabazz will spend the next eight hours meticulously sifting through the box, rediscovering faces and city landscapes that he had forgotten even photographing. He scans some of his faves. Then he posts them on his Instagram, sometimes with an accompanying music track, sometimes not. Within seconds, likes and comments from his one-hundred-thousand-plus followers of all ages, from around the world, start flooding in. Those frozen bits of time still elicit the same delight, pride, and awe as they did in the ’80s and ’90s.

“I think I’m an alchemist,” Shabazz tells me. “I freeze time and motion.” It is as if this moniker were a new revelation, the result of now having the time and space to reflect on his odyssey into professional photography. When examined as a whole, Shabazz’s brand of portraiture cannot, and perhaps should not, be characterized simply as street photography or fashion photography. He says he is an alchemist. I believe him.

In the early ’70s, the Shabazz home in Red Hook was alive and buzzing with the funky sounds of Marvin Gaye, the Jackson 5, and Earth, Wind & Fire. And books. There were tons of books. Books on politics, photography, and culture were neatly organized on a massive wall of shelves. “My father had a really vast library of books, and I would go through every single book he had in the house,” he remembers. “National Geographic, Life magazine—all those publications informed me.” Shabazz, who had developed a serious speech impediment when he was quite young, discovered that while he struggled to communicate verbally, he could get lost in the worlds of his father’s books and album covers. Leonard Freed’s Black in White America (1968) was among Shabazz’s favorites. He flipped through it so often during his adolescent years that the book had fallen apart by the time Shabazz reached high school.

To escape the brewing trouble that was ensnaring many Black boys in Brooklyn in the waning years of the Black Power movement, Shabazz made the decision to enlist in the army as soon as he could. In 1977, a seventeen-year-old Jamel Shabazz was assigned to a post just outside Stuttgart, Germany. He followed the lead of an older Black soldier who carried his camera with him everywhere he went. “For practically everybody who was in the military, a camera was the biggest thing to have. Because for them, they were getting away for the very first time. So it’s through that experience that they brought home photographs.” Shabazz’s Canon AE-1 became his closest companion. He snapped pictures of everything he saw and tasted as he moved through Germany. He became something of an ethnographer, translating the subversive spirit of the Black poets he was discovering—Sonia Sanchez, Nikki Giovanni, and Amiri Baraka—as he manipulated the camera’s aperture and shutter settings.

After one tour in the army, Shabazz returned home to Brooklyn, in 1980, a changed man. “I came home a revolutionary,” he recalls. No longer enticed by the lures of street life, Shabazz wanted to create real change in his community. The 35mm camera that he had learned to use in the army would be key to his revolutionary arts ministry. Shabazz proclaims, “My journey has never been about wanting to be a photographer. The primary vision was to save our people.” His mission was to mobilize those the Black Panthers referred to as the “lumpen proletariat”—gangsters, pimps, and sex workers—who were most vulnerable to labor exploitation, drug addiction, and homelessness. Many of Shabazz’s childhood friends made up this underground economy. And now, the man who had once struggled to speak was committed to using his camera to initiate conversations with these old friends, and even strangers, across Brooklyn and Manhattan.

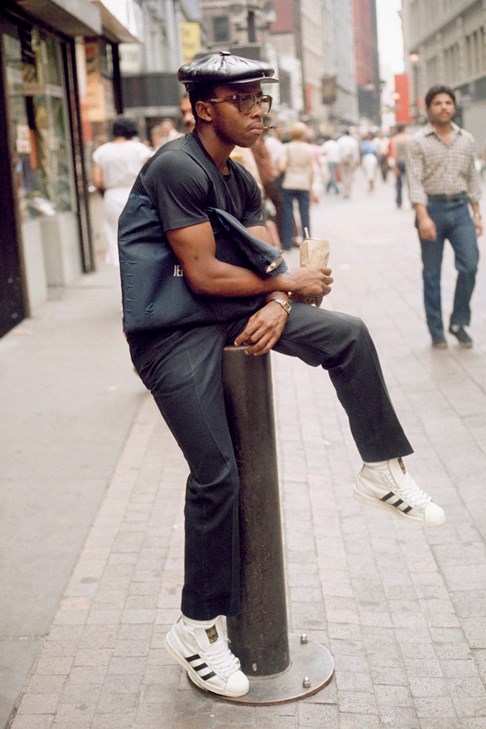

Those early years were less about following some industry craft standards and more about using the special relationship between photographer and subject to establish a deeper spiritual connection. Shabazz was channeling James VanDerZee’s ability to capture pure human emotion and Gordon Parks’s versatility, allowing him to blend different genres of photography. He quickly learned that one could not approach Black Americans, particularly the street-oriented folks he wanted to reach, dressed like a slouch. “I think that some might view me as sort of dapper,” he says. “And it made people more open to me when they saw me.” They could instantly see that Shabazz understood the style economy of the block, that he spoke a common language. He was an insider. This insider status granted Shabazz access to their inner selves—an intimacy reflected in his subjects’ body postures and poses—and gave him a chance to lovingly prophesy alternative possibilities for their futures.

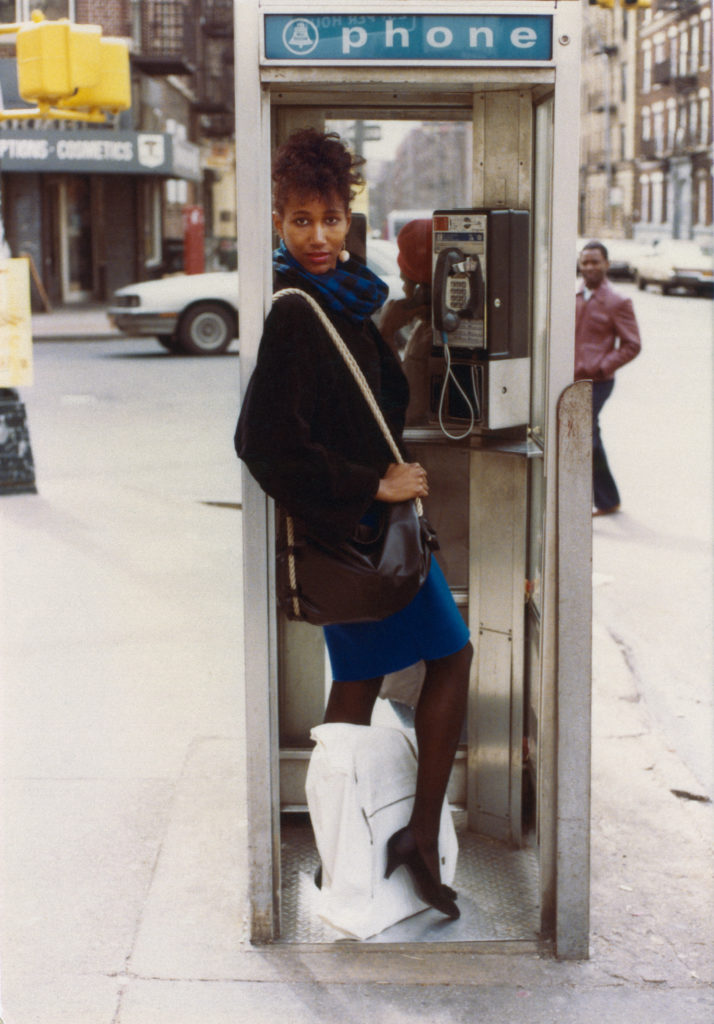

Photography was also saving Shabazz’s life, especially once he was hired, in 1983, as a corrections officer at the infamous Rikers Island prison. Long shifts “witnessing the inhumanity that men would inflict on other men,” as he describes it, were a daily part of this job. Shabazz says of his frequent after-work photoshoots, “I had to go out on the streets and gain my balance by tapping joy, tapping into brotherhood and unity.” He would photograph around East Flatbush, often using his 28mm wide-angle lens. Then maybe he would head to the Lower East Side, where he would switch to his 50mm lens while chatting with and photographing sex workers dressed in their ’80s fly-girl fashions: gold bangles and bamboo earrings, leggings and heels. Other times, he might spend a Sunday in Harlem, catching the Masons, Eastern Stars, and church-going folk in their finery, before heading to Central Park, to Midtown, then Delancey Street. “I would cover a lot of areas. I’d even get on the train and just look at neighborhoods that were interesting, and get off, and go photograph them.” He walked so much that he repeatedly wore holes in the soles of his designer shoes. The more he photographed, the more he could distance himself from the horrors of the prison.