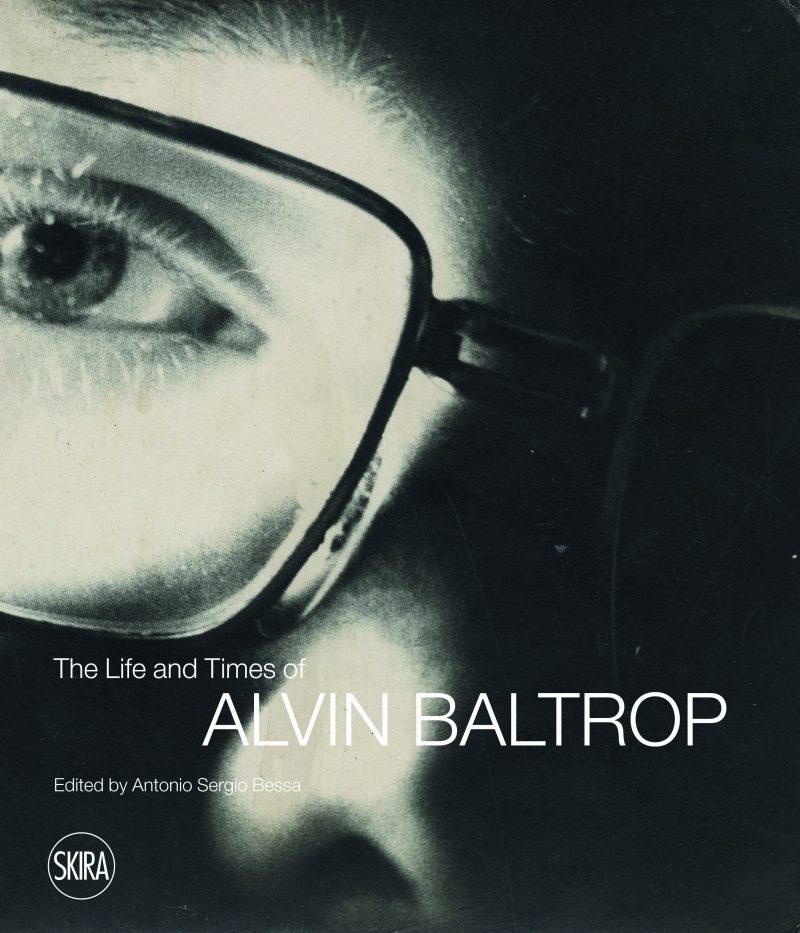

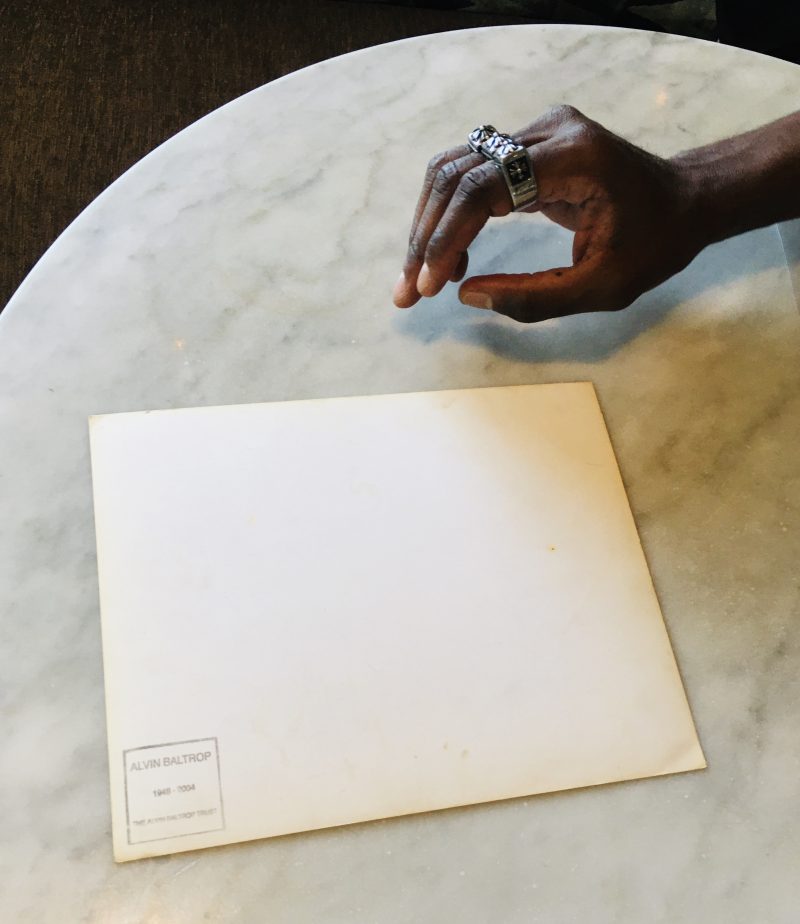

SOLD. Alvin Baltrop (1948-2004), Authentic Vintage Estate Photograph

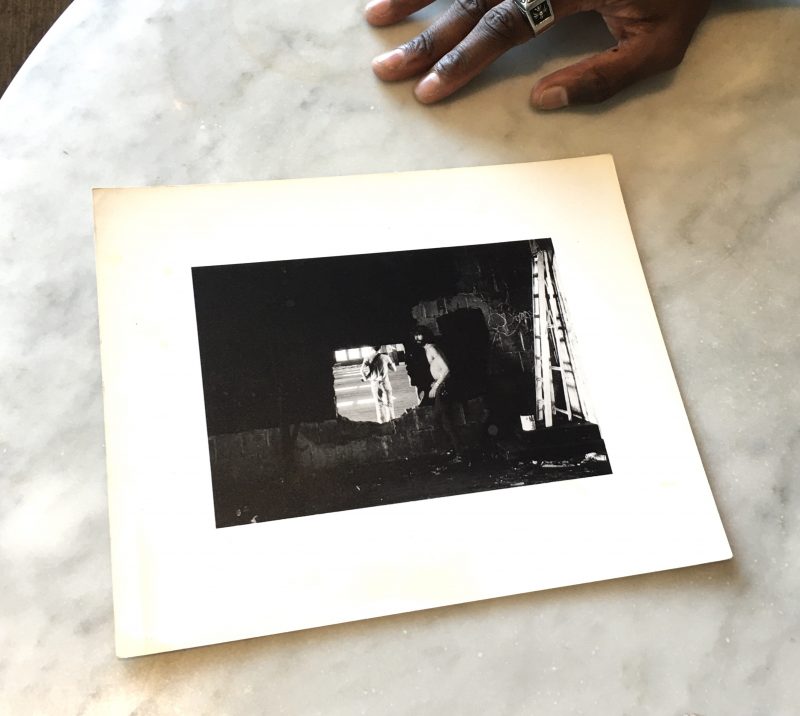

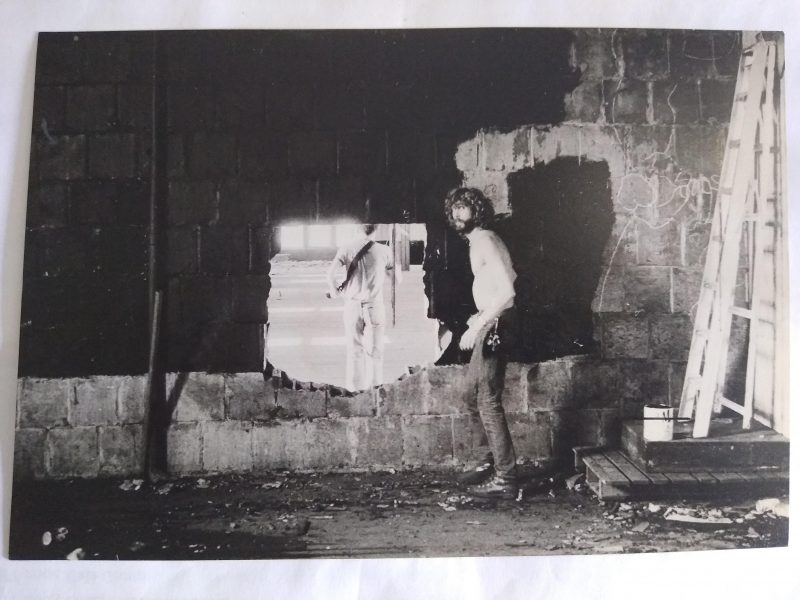

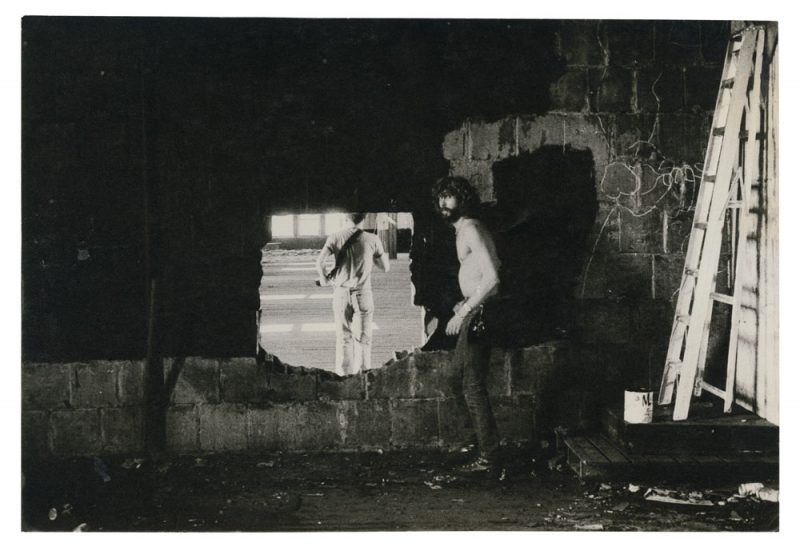

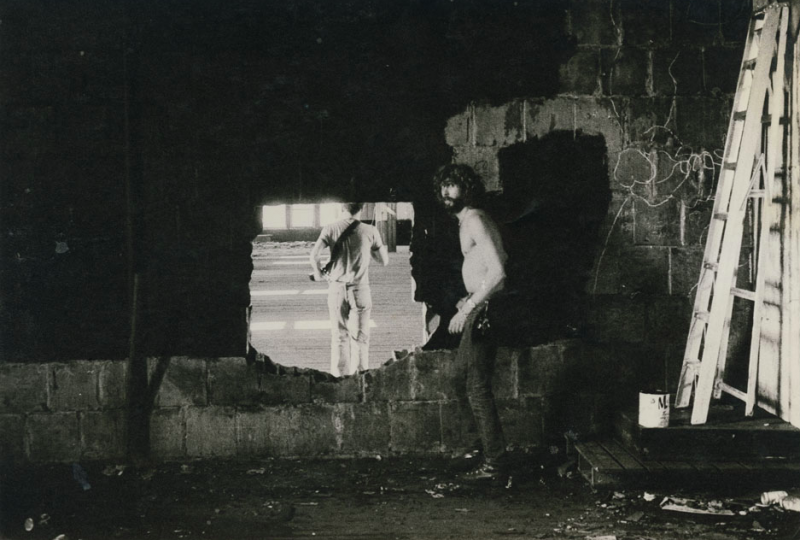

The Piers (Tava from behind), n.d. (1975-1986)

(‘The Piers’ photography series)Alvin Baltrop: Photographs of a Dystopian Past

Greenwich Village’s Hudson River piers have always held a certain clandestine fascination for some segment of the public. After an automobile crash caused the elevated West Side Highway to collapse in December of 1973, Piers 18 – 52 fell into a derelict state, creating a dystopian yet incredibly private space for LGBTQIA+ New Yorkers to gather for surreptitious activities. For a young, bisexual, African-American photographer named Alvin Baltrop, it created the perfect setting for his voyeuristic style capturing an evolving community of queer, trans, and homeless individuals that made their home amongst the ruins.

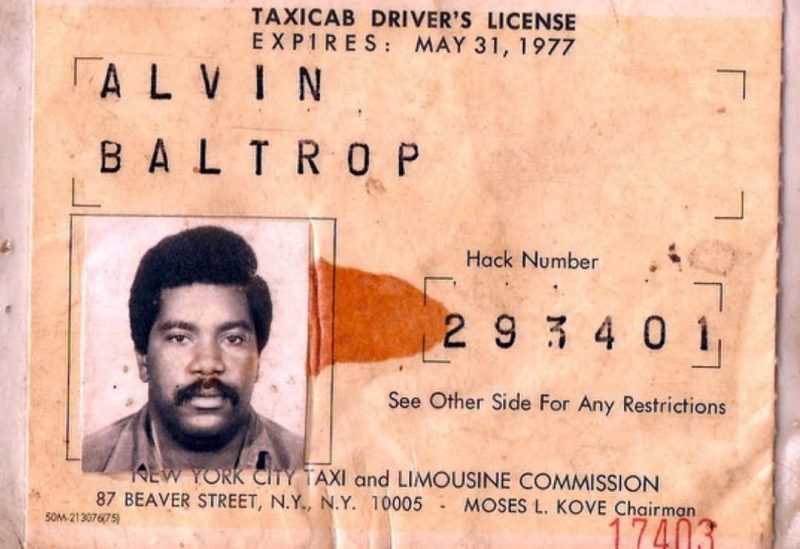

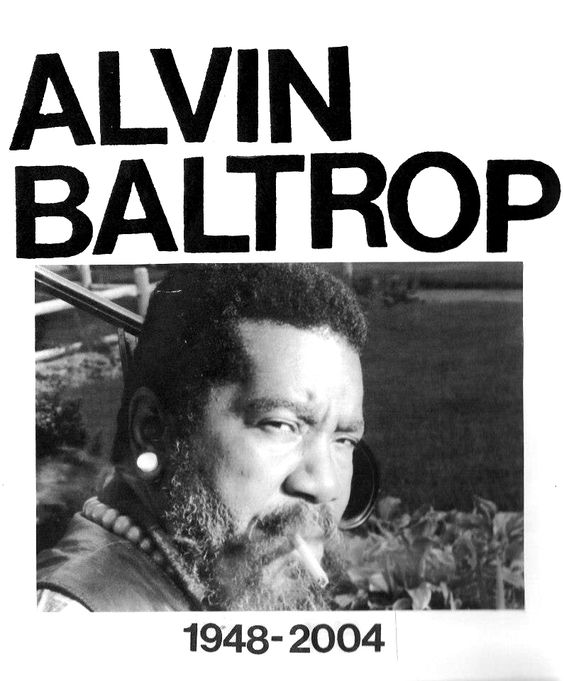

Alvin Baltrop was born on December 11th in 1948 to a single mother and was raised in the Bronx. Baltrop showed a tendency for creativity early in his life. In junior high school, he showed a strong interest in photography and taught himself how to develop film. However, his mother, a Jehovah’s Witness, strongly disliked his photos and frequently threw them out, leading him to run away from home during his teens. In 1969, Baltrop joined the Navy during the Vietnam War, practicing his sketching skills on his fellow sailors and creating a make-shift developing lab in the ship’s sickbay. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Baltrop was honorably discharged in 1973 to study art at the School of Visual Arts. In his practice, Baltrop became increasingly attracted to the grittier sides of Lower Manhattan’s queer cultural scene, where he discovered a burgeoning community growing amid the Hudson River pier ruins.

During the 1970s and 80s, the Hudson River Piers acted as both a cradle and a cage for queer and homeless populations. After the 1973 highway collapse cut off the piers from the rest of the Greenwich Village, they became a relatively under-policed yet highly accessible area, luring populations of homeless teenagers fleeing homophobic and transphobic persecution from their parents as well as cruisers looking for a place to engage in public sex and naked sunbathing. While it provided well-needed refuse for these groups, it also subjected them to increased rates of sexual assault and harassment, exposure to drug use, and, in worst cases, violence or murder. For these reasons, the piers terrified Baltrop, but, over time, he developed a morbid interest in documenting the characters and architecture he found there.

In 1975, Baltrop purchased a moving truck and stationed it directly adjacent to Pier 52 (where the Whitney Museum now stands) as a mobile developing lab and home for himself while he photographed his subjects. His photographs bestow a classical yet dystopian perspective on the cavernous ruins and their inhabitants. While most of his pictures depict seedy topics (cruisers having public sex and the police discovering murdered and mutilated bodies), his lens also focuses on the piers’ capacity for humanity: Men and women cuddling with same-sex partners, naked bodies engaging in intimate conversations, teenagers playing and climbing amongst the ruins, and friends sunbathing. Gradually, Baltrop became one of the community’s most trusted members. He famously photographed his personal friend, trans activist Marsha P. Johnson, and he provided dating advice and sexual health resources to newly-arrived teenagers during the AIDS crisis.

However, in 1986, the city began the process of demolishing these piers. Displaced from this community, Baltrop moved to the East Village, where he struggled to pay rent as a part-time bouncer for a gay club on 2nd Avenue and East 4th Street. Although Baltrop printed and attempted to display the majority of his photographs in local galleries, his race and the perception of his work as “lewd” largely alienated him from the East Village and professional art scenes. While contemporaries like David Wojnarowics, Peter Hujar, and Robert Mapplethorpe grew more popular during the 1990s and 2000s, Baltrop’s work remained in obscurity on his apartment floor for most of his life. Humorously, visitors were told to “catwalk” through the piles of photographs while visiting his home. His work is mostly known and collected now because of the 2008 article and photo spread, “Alvin Baltrop: Pier Photographs, 1975-1986” published by the ArtForum’s Douglas Crimp, which inspired feature exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art and Bronx Museum of the Arts held in 2019.

Baltrop never lived to see this recognition. After he died of cancer in 2004, it was Baltrop’s close friend and artist Randal Wilcox who saw the value in his creative works and saved his photographs and journals, placing them in perpetual care for future generations.

The piers and Alvin Baltrop’s legacies are deeply intertwined with our neighborhoods’ LGBTQIA+ historyand its intersections with racial and socio-economic diversity. If you’d like to learn more about the Hudson River Piers (as well as other places of intersectional Queer history within Greenwich Village, the East Village, and NoHo), then explore our 2022 Village Pride Tour via Urban Archive as well as our Civil Rights and Social Justice Map. You can also visually explore the piers further via our James Cuebas and Jack Dowling Collections in Village Preservation’s Historic Image Archive.

Further Reading and Sources Referenced:

- Douglas Crimp’s February 2008 article and spread “Alvin Balrop: Pier Photographs, 1975-1986” for ArtForum

- Holland Cotter’s 2019 article “He Captured a Clandestine Gay Culture Amind the Derelict Piers” for The New York Times.

- The 2019 Life and Times of Alvin Baltrop exhibition by the Bronx Museum of the Arts

- Najja Sayej’s 2019 article “Alvin Baltrop: Remembering New York’s Forgotten Queer Photographer” for The Guardian, US Edition.

- Jesse Doris’ 2019 essay “Down and Out on the West Side Piers” for Aperture Magazine.

Alvin Jerome Baltrop was born December 11, 1948, to Dorothy Mae Baltrop shortly after she had moved from Virginia to the Bronx with her eldest son James. He began photographing with a twin-lens Yashica camera in his early teens. Baltrop joined the US Navy in 1969 and served in Vietnam, where he photographed fellow sailors doing chores or at leisure. He received an honorable discharge in 1972, and went on to attend New York City’s School of Visual Arts from 1973 to 1975. It was during that period that Baltrop started documenting the gay communities in the West Village area and along the piers. Late during the 1990s, artist John Drury nominated Baltrop for a Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation Award. Baltrop had few exhibitions in his lifetime, and his work only gained critical recognition after his death, particularly after art critic Douglas Crimp published an article about his work for Artforum in 2008.

The photographs of Alvin Baltrop (1948-2004) were virtually unknown during the artist’s lifetime. A working-class African American many of whose photographs are sexually explicit, Baltrop encountered only rejection. In the past decade his work has belatedly begun to be exhibited, including at Third Streaming and MoMA/PS1 in New York City, the Reina Sofia in Madrid, and the Contemporary Art Museum, Houston. By far the largest cache of Baltrop’s extant photographs depicts the scene at the dilapidated Hudson River piers adjacent to Greenwich Village and the Meat Packing District. During the 1970s and into the 1980s, when Baltrop photographed there, the piers were a site of pleasure and danger for men seeking sex, sunbathing, making a provisional home, or just hanging out and taking in the splendor of the industrial ruins. More nefarious deeds also took place: theft, gay-bashing, even murder.

Baltrop claimed to be terrified of the place initially, but also intrigued; he began taking photographs, he said, as a voyeur. Eventually he became a denizen of the piers, at times living nearby in his moving van, which also provided his source of income. His rapport with certain of the pier’s users is clear enough in the straightforward portraits he made there, including one of Marsha P. Johnson, the beloved trans activist whose dead body would, in 1992, be discovered in the Hudson River near the very place where Baltrop likely took her picture. The rapport is even clearer in photographs of men removing their clothes to pose for Baltrop. And some photographs are so intimate as to suggest that the sex they depict is staged for his camera – or, indeed, that photographing was part of the action. Among these are routine sex acts, but there are pictures of kinky BDSM action, too.

Baltrop seems to have wanted above all to portray the environment in which these activities took place, the piers themselves. Sometimes you have to look closely even to locate people within the disintegrating remains of the pier sheds, much less see what they’re up to; and in any case they might simply be sitting on a window ledge or standing on a mooring. Or, more disquieting, they might be prone bodies covered with blankets, presumably sleeping. In many cases, there are no figures at all; Baltrop’s subject is simply the architecture in its vastness and melancholy.

Baltrop printed the majority of his photographs small, no more than 5×7 inches (approximately 13×18 centimeters), although he printed a few images considerably larger. There are variant sizes and crops of a few pictures. Because of the small size and density of information in many of the photographs, especially those of one pier taken from the distance of another, adjacent pier, you have to get very close to the picture to really see it. It has been noted that Baltrop’s pier photographs constitute a significant record of a lost era of New York industrial landscape and gay culture’s pre-AIDS history. There is truth in that view, but it suggests that Baltrop’s project was essentially documentary in nature, whereas the intimacy of the pictures, their studied compositions, their attention to the play of light and shadow testify to a wider ambition.

Text by Douglas Crimp