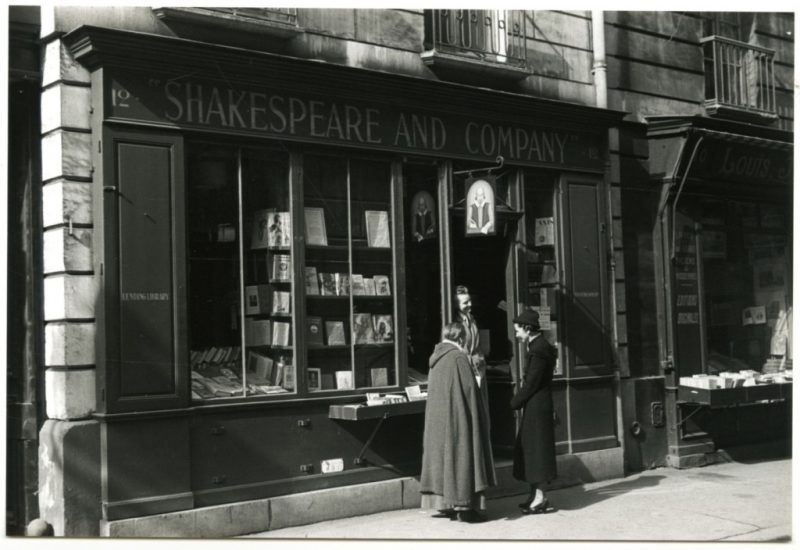

SOLD. Gisele Freund (1908–2000), ‘Shakespeare & Company, Paris, 1936

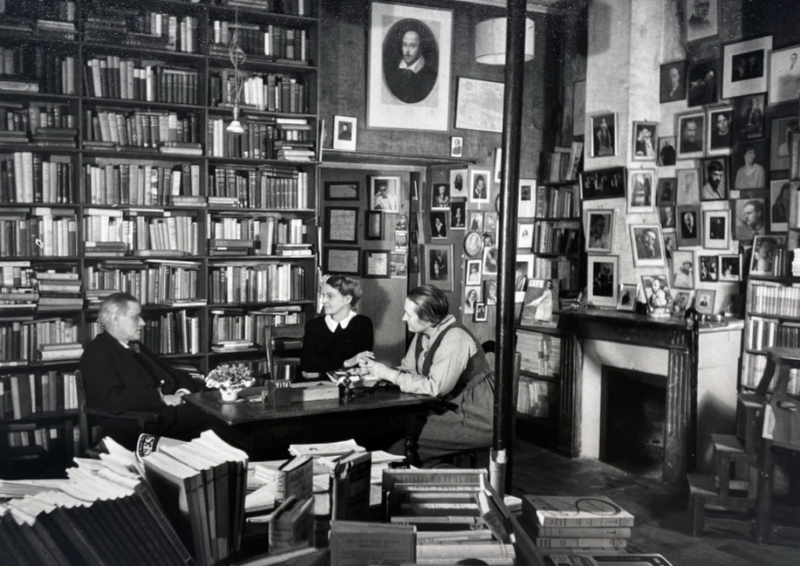

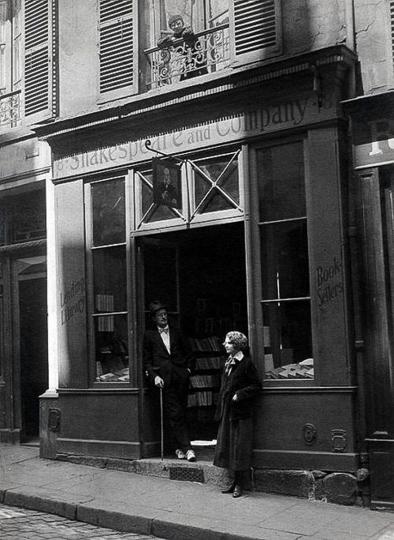

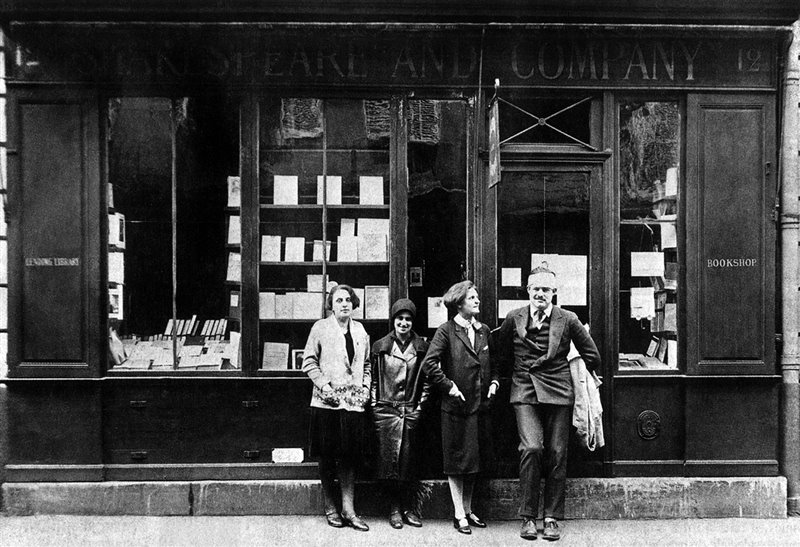

“James Joyce with his publishers, Sylvia Beach and Adrienne Monnier, in Sylvia’s bookshop “Shakespeare and Co., Paris”; 1938; Collection of Gelatin Silver Prints, Private Collection (sold at auction in New York).

Gisèle Freund

From her photographs of a rally in Berlin to her insightful portraits of Evita Perón, Gisèle Freund captured the people who shaped the early twentieth century. Freund photographed a May Day rally in 1932 that served as a harbinger of Hitler’s rise to power. She fled Germany for Paris in 1933 and earned her PhD in 1936 with a dissertation on the social impact of photography. In 1941, after more than a year in hiding, she left occupied France for South America, where she began publishing books and doing documentary reportage for magazines, including an infamous 1950 piece for Life Magazine on General Perón and his wife. In 1953 she returned to Paris, where she continued to write and photograph contemporary artists and writers and became president of the French Federation of Creative Photographers in 1977.

“A whole life…is terrifying and wondrous,” exclaimed Elsa Triolet upon seeing a show of Gisèle Freund’s color portraits at the Paris Musée d’Art Moderne in 1968. With these words she described the extraordinary life and work of Gisèle Freund, European intellectual and writer, sociologist, historian of photography, a socialist, a Jew, and one of the world’s greatest photographers.

Freund was born into a wealthy Jewish family in the Schöneberg district of Berlin on December 19, 1908. Her father, Julius Freund (1870–1941), a textile merchant with a passion for collecting nineteenth- and twentieth-century German art, introduced Gisèle to the work of Karl Blossfeldt (1865–1932), a botanist who explored the formal elements of beauty in plants through photography. Her mother Clara (née Dresel) died in 1947. Upon graduation from high school, her father presented his daughter with a Leica camera, which Gisèle later said became “her companion all her life.” In 1929, Freund began studying sociology and the history of art, first in Freiburg and then from 1930 at Frankfurt University with sociologist Karl Mannheim (1893-1947) and her tutor, Norbert Elias (1897-1990). She also attended lectures at the affiliated Institute for Social Research, where her teachers included Theodor Adorno (1903–1969).

During her university years, Freund documented life in Frankfurt. On May 1, 1932, Freund photographed a May Day rally that erupted in chaos against the National Socialist government. Later she would say, “In January 1933, Hitler became chancellor of the Reich and established his dictatorship in Germany. Many of those I photographed on that May Day in 1932 became members of the Nazi party; others ended up in concentration camps.”

Being Jewish and a fervent opponent of National Socialism, Freund was an overt activist and a member of an anti-Fascist group. When one of her friends was imprisoned and murdered, Freund was told she must leave the country. On May 30, 1933, with little more than her camera, and with photographic negatives taped around her body to get past the border guards, Freund fled Germany. She did not set foot on German soil again until 1957.

Among the thousands of German refugees pouring into France, Freund arrived in Paris in 1933. Forced to give up her studies in Frankfurt, she continued her research at the Sorbonne, working on her dissertation in the Bibliothèque Nationale, where she met Walter Benjamin (1892–1940), writer and literary critic, himself a recent German refugee, and a Jew. They shared a mutual desire to displace the empty, iconic forms of fascist art and writing with an intimate humanism in the arts, and a need to restore meaning and value to a world emptied of content.

For Freund this meant photographing people as thinking, feeling human beings involved in the aesthetic commonality of letters, books, and paintings. By 1935 she had met Adrienne Monnier (1892–1955), poet, feminist writer, publisher, and a central figure in the contemporary avant-garde scene in France. In 1936 Monnier published Freund’s ground-breaking doctoral dissertation on photography in nineteenth-century France, the first thesis of its kind to address the value and importance of photography as a social, democratizing force.

By 1939, with Monnier’s assistance, Freund had photographed some of the greatest literary and artistic figures of the twentieth century: Simone de Beauvoir, Jean-Paul Sartre, James Joyce, Henri Matisse, Samuel Beckett, T. S. Eliot, Virginia Woolf, Jean Cocteau, André Breton (1896–1966), Colette, André Malraux, Paul Valéry, and Sylvia Beach (1887–1962). In 1938 she began taking portraits in color, becoming the first woman photographer in France to use 35mm color film and color slides, the latter a new technology and method of showing her work that Freund would continue throughout her life.

Freund did not attempt to capture the essence of a person in one photograph, but preferred to show a changing stream of consciousness. Especially fond of writers, she photographed them in their homes or in the atmosphere they were most familiar with. Strongly influenced by the realist movement among American writers, Freund stated she “did not make portraits” her profession and “never owned a photography studio.” Refusing to pose her subjects, Freund learned that by engaging her sitters in conversation she could evoke a sense of vitality and loved using color because it “came closer to life.” Ahead of her time, she changed photographic portraiture by refusing to use staging, props, makeup, or retouching to “beautify” the image.

Though Freund became a naturalized French citizen through marriage in 1936, being Jewish meant she had to face displacement again. In 1940 she fled occupied Paris for southern France where she lived underground for a year. In her memoirs (The World in My Camera) she wrote:

On June 10, 1940, the government left Paris. Three days later, directly before the German troops arrived, I left at dawn on a bicycle—the trains were no longer running. On the rack I had attached my little suitcase, the same one I had brought with me to Paris seven years before. I found asylum in a small village in the Dordogne. Several weeks later, I was informed that my husband had been made a prisoner of war. He got word to me that he would try to escape and succeeded a few months later. I met him in the still unoccupied part of France. He told me he would go back to Paris to fight the Germans in the Resistance, and advised me to leave the country as soon as possible. Being of German origin, undoubtedly listed by the Gestapo, and now the wife of an escaped prisoner as well, I actually feared for my life.

Finally, in 1941, she found refuge in Argentina thanks to Victoria Ocampo (1891-1979), director of the periodical Sur in Buenos Aires, who supplied her with a boat ticket and arranged a visa. Ocampo was at the center of the Argentinean intellectual elite, and through her Freund met and photographed many great writers and artists, such as Jorge Luis Borges and Pablo Neruda.

Freund became cultural attaché for the Ministry of Information of Free France while in South America, and founded “Ediciones Victoria” to publish books about France. While the war continued overseas, Freund focused on producing documentary reportage and films on remote areas such as Tierra del Fuego and Patagonia in 1944, and continued her travels through Chile, Peru and Bolivia, Brazil and Ecuador. In all these countries she wrote stories published by European and American magazines.

Upon her return to Argentina she was commissioned in 1950 to do a story on General Juan Perón (1895–1974) and Evita Perón (1919–1952), who was then at the height of her power. That same year Life magazine published some of Freund’s revealing photographs of Evita, provoking a diplomatic incident—Life was put on the blacklist in Argentina and Freund barely escaped the country with her negatives.

When invited to lecture in Mexico, Freund fell in love with Mexican culture, especially its art, and remained there for two years, becoming friends with painters Diego Rivera (1886–1957) and Frida Kahlo (1907–1954). However, when she wished to leave for the United States, she had problems with the American consulate. It was 1952 and the era of McCarthyism.

In 1947 Freund had signed a contract with Magnum Photos, beginning a seven-year association with the historic photographic news agency founded by Robert Capa (1913–1954) and Henri Cartier-Bresson (b. 1908). Freund had returned to Paris in 1953, now her permanent home, but by 1954, at the height of the cold war, Freund was blacklisted in America, declared an undesirable by the FBI, and pressured to break with Magnum in 1954.

Gisèle Freund spent the rest of her life in France, living in a book-lined Paris home, writing memoirs, and working on numerous books. She became president of the French Federation of Creative Photographers in 1977, and in 1980 was the first woman to receive the Grand Prix National des Arts from France. François Mitterrand (1916–1996) appointed her an Officier des Arts et Lettres in 1982, and Chevalier de la Légion d’ Honneur the following year. In 1991 she was the first photographer honored with a retrospective at the Musée National d’art Moderne in Paris.

Gisèle Freund died in Paris on March 31, 2000.

Photography and Society. Boston: 1980.

Essential reading for any student of photography. Freund’s original dissertation was published in 1936, however, she would revise and extend her thesis in 1974 to produce her seminal work in French, Photographie et Sociétié. The first section of this book was her original doctoral thesis at the Sorbonne.

Gisèle Freund, Photographer. New York: 1985.

Shows powerful photoreportage of Hitlerite students in Frankfurt in 1932, hopelessness and poverty in Newcastle-upon-Tyne in England during the Depression, and some of the greatest writers of the century gathered in France to defend freedom against the threat of war and fascism in 1935. Especially memorable are her portraits of Leonard and Virginia Woolf. Many photos are accompanied by Gisèle Freund’s personal notes and reminiscences. Excellent selected bibliography.

The World in My Camera. New York: 1974.

Her memoirs. Freund states she was twenty years old in May of 1933, and mentions her husband, who had been a prisoner of war, and worked for the Resistance in France. She also discloses she had polio as a child and lost the strength in her hips for the rest of her life. The negatives Freund had taped to her body in escaping Germany appeared in Le Livre brun in 1933 and were reproduced throughout the world. They were dangerously incriminating, showing Nazi brutality of students. Fascinating, important reading for historians.

James Joyce in Paris: His Final Years. New York: 1965.

Joyce was one of the first writers Freund photographed in color for Time magazine in 1939, when his last book, Finnegans Wake, was published. Freund collaborated with Verna B. Carleton to produce this book twenty-four years after Joyce’s death in 1941. Moving and unforgettable.

Gisèle Freund: The Poetry of the Portrait. Munich: 1989.

Part of the “Masters of the Camera” series published by Schirmer Art Books, this small book contains forty of her best known photographs of writers and artists in color, nine of whom won the Nobel Prize for Literature. Preface by Freund and good biographical notes and bibliography.

de Cosnac, Bettina. Gisèle Freund. Ein Leben. Zurich: Arche, 2008.

Flavell, M. Kay. You Have Seen Their Faces: Gisèle Freund, Walter Benjamin and Margaret Bourke-White as Headhunters of the Thirties. Berkeley, California: 1994.

This collection of letters examines Freund’s opposition to the dehumanizing use of photography and film by propaganda machines created in Germany, Italy, Spain and Russia. Flavell states, “Benjamin and Freund, by virtue of their Jewish backgrounds, themselves belonged to the class of the stigmatized and their work was performed against a background of exile and persecution.” In her closing notes Flavell says, “I am also deeply grateful to Dr. Gisèle Freund for her friendship and assistance during 1989–91.” Contains information not found in other documents, plus an excellent bibliography.

Gisèle Freund. En el sur tan distante. In the oh-so-distant south. Madrid: La Fabrica, 2021. Texts by Juan Alvarez Marquez and Juan Manuel Bonet. This book draws on the Gisèle Freund archives (photographs, 30 boxes of files and books from her library) donated to the Institut Mémoires de l’édition contemporaine in 2011.

Gisèle Freund. Portrait. Entretiens avec Rauda Jamis. Paris: Des Femmes, 1991.

Heron, Liz, and Val Williams, editors. Illuminations: Women Writing on Photography from the 1850s to the Present. London, New York: 1996.

A beautiful book filled with writers’ observations on photography. Beginning with Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s, “On the Daguerreotype,” it includes Freund’s masterful “Photography During the July Monarchy, 1830–1848.”

Kramer, Hilton. “The World in Gisèle Freund’s Lens.” The New York Times, December 28, 1979.

Lehmann-Haupt, Christopher. “Books of the Times.” The New York Times, July 2, 1980.

Women in Photography International Archive. Galleries: Archive 3. July 2000-August 2000. Historical Portfolio: “Gisèle Freund” by Peter Palmquist (1936-2003). http://www.womeninphotography.org/wipihome.html.

Essay contains vivid, descriptive writing about Freund’s Newcastle pictures of Depression poverty in the north of England, and how Life magazine published them opposite photos of the Queen Mother and princesses Elizabeth and Margaret Rose, in response to the Simpson scandal. Fascinating reading about Freund and Margaret Bourke-White being thrown out of Magnum by an anxious Robert Capa, who was desperately trying to recover his American passport and not get blacklisted for being a Communist. Includes three famous photographs Freund took of Colette, Henri Matisse, and Simone de Beauvoir.