‘THE TRAVELERS’ Book by Elizabeth Heyert

Hardcover: 80 pages / Excellent condition

Publisher: Scalo Publishers (February 28, 2006)

Language: English

Dimensions: 13 x 10 x 1 inches

Asking USD$125

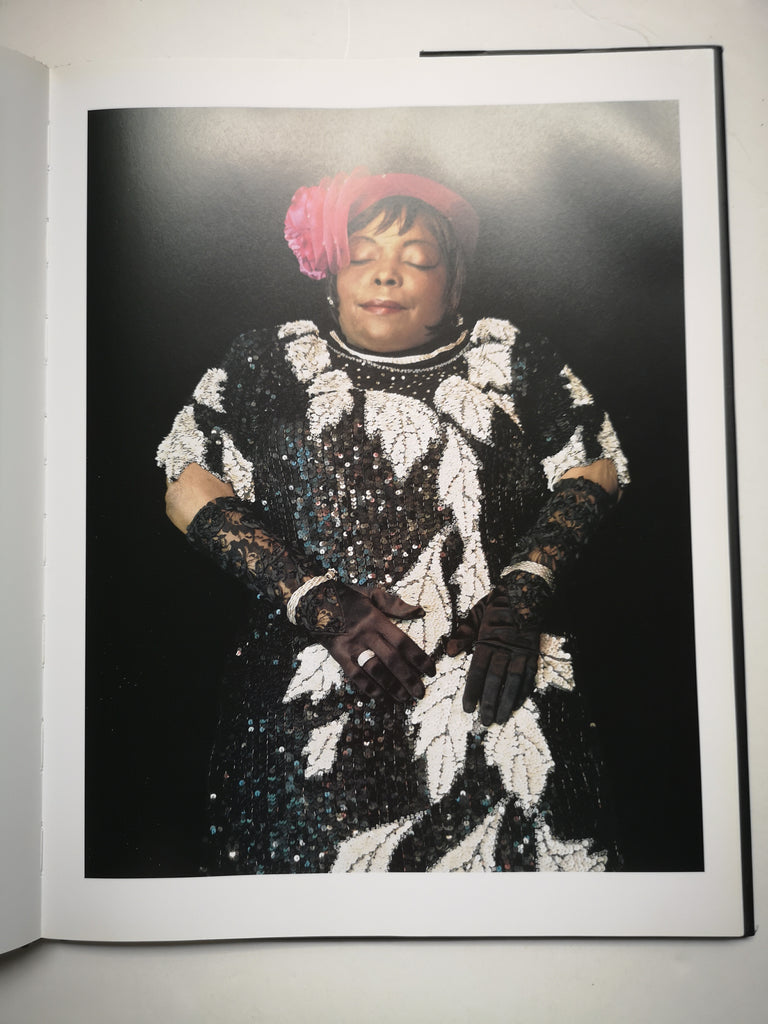

In 2003/2004 Elizabeth Heyert photographed the bodies of more than thirty people at the Harlem funeral parlor of Isaiah Owens who prepared the corpses for their last journey. She would take pictures early in the morning, after the families had said goodbye to their loved ones the previous evening and before the service later in the morning.

This book is a unique contribution to contemporary portrait photography. It is movingly intimate but never sensationalist. As Heyert explains, there is a historical dimension to these images: “I was aware that I was also photographing a community from the past, a vanishing piece of cultural history. Some of the people I photographed left a brutal life in the Depression-era South to move to Harlem, where many of the southern religious traditions were re-established. Younger people were born and died in Harlem, but were still buried according to the old style, dressed for going to the party (Isaiah Owens) but in snazzy track suits instead of burial gowns. With Harlem rapidly changing, these traditions are fading. I hope my photographs will tell some small part of the story of a passing generation and their way of death.”

THE TRAVELERS, Conversation with Elizabeth Heyert

How did this project begin?

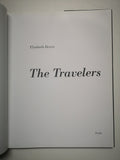

I saw an article in the paper about a funeral director in Harlem who did this old-style, Southern Baptist, traditional burial in which people were dressed up to be prepared to enter paradise. So I went up to Harlem. There was a woman named Betty Edwards in an elaborate coffin lined with white satin. She was in a big white hat, a white suit and she looked amazingly beautiful. She had a round face, a sweet expression. I was so moved by the idea of death being an occasion for which you’d put on your finest. I took a black and white picture, but it was simply a record of somebody in a coffin, a façade. But I kept looking and looking at the image; it was as if she was surrounded by all this stuff that shouldn’t be there: the elaborate coffin, the quilted satin pillow, the flower arrangements. I thought it would be so wonderful to stand her up, light her well. I lived with the image for three weeks, working on the Polaroid with a magic marker, thinking that there must be a way I could do this.

What happened with the second person you photographed?

It was Margaret Forrest, who had just died at 101. I went up to the funeral parlor. She was so beautiful you can’t imagine, all in pink with a fabulous purple hat. I asked as much as I could about her, tried to learn her story. Then I asked if we could prop up the coffin on the platform where people deliver eulogies and it actually worked. I brought a large dark cloth to place under the body, then kind of taped up the cloth on the furniture and stacked hymnals on top to hold it down. I didn’t understand yet exactly what I would need to do to make a real portrait. But once I took her away from the elaborate trappings, it was as if I knew her. I could see who she was.

As I looked through the ground glass, I choked up. It stopped being about death and became about her whole life. A portrait is always about the coming together of two people, and that’s what happened with her. It didn’t seem like she wasn’t there anymore, or as if I was looking at a facade. I could feel her humanity. I was just shaking and filled with excitement. I decided then that I wanted to photograph a whole community, a community of the dead.

THE TRAVELERS, In Memorium, Naarden, The Netherlands

How long did the project take?

From February 9, 2003 to March 14, 2004.

What was the actual process?

I used an 8 x 10 Deardorff, and shot three different kinds of 8 x 10 inch sheet film: color slides, color negatives, and black and white. With each person I knew I wouldn’t have a second chance. I felt that I was recording history. I wanted to make sure I had whatever I might need to print the photograph. We brought one studio light, and then used a 60’s arc light that we found there, and some fill cards to try to overpower the weird mixture of ambient light. It was difficult to do the sort of beautiful portrait lighting I wanted to do, because the funeral parlor had fluorescent lights and pinkish spotlights. Each shoot took about three hours, and the exposures were up to eight minutes long. Usually it was in the very early morning, because the family would gather the night before to see what their loved one looked like after the body was prepared, and approve. We’d get permission, get the release signed, and I’d get a phone call to be in Harlem in a few hours. The service would usually be at 10 a.m., so I’d go there at 5 or 6 a.m. and we’d work as fast as we could. In other words, we worked after the body was prepared for the service, but before being buried. There was a lot of time pressure. During the shoots, once someone was placed in the coffin over the black cloth I’d spend a lot of time manipulating the big camera. I was hanging over the body, high up on a ladder, always straddling a coffin with a big heavy lid. Then just before I took the photo, the funeral director would come in and I would ask him to delicately move the hands or head to create the most natural pose, do manually what I would usually explain to a living person who was sitting for a portrait. I never touched the bodies.

For a year I was perpetually on call. I never wanted to turn anyone down. I shot 33 portraits; there are 31 portraits in the project.

Were there any elements that recurred in these photos?

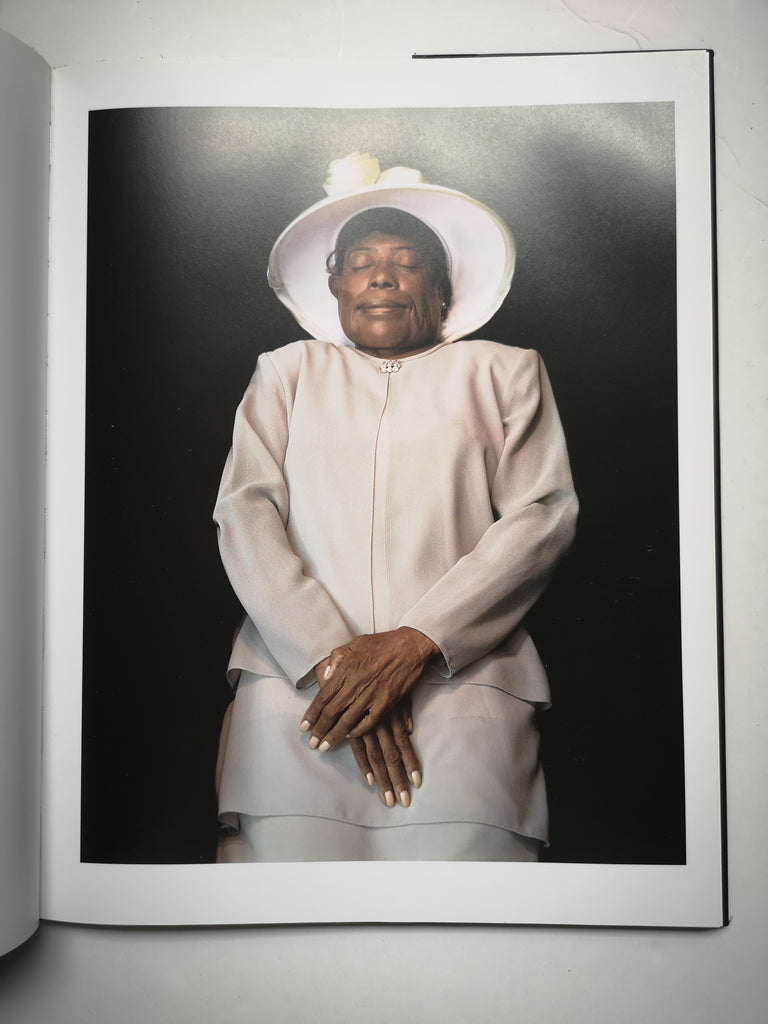

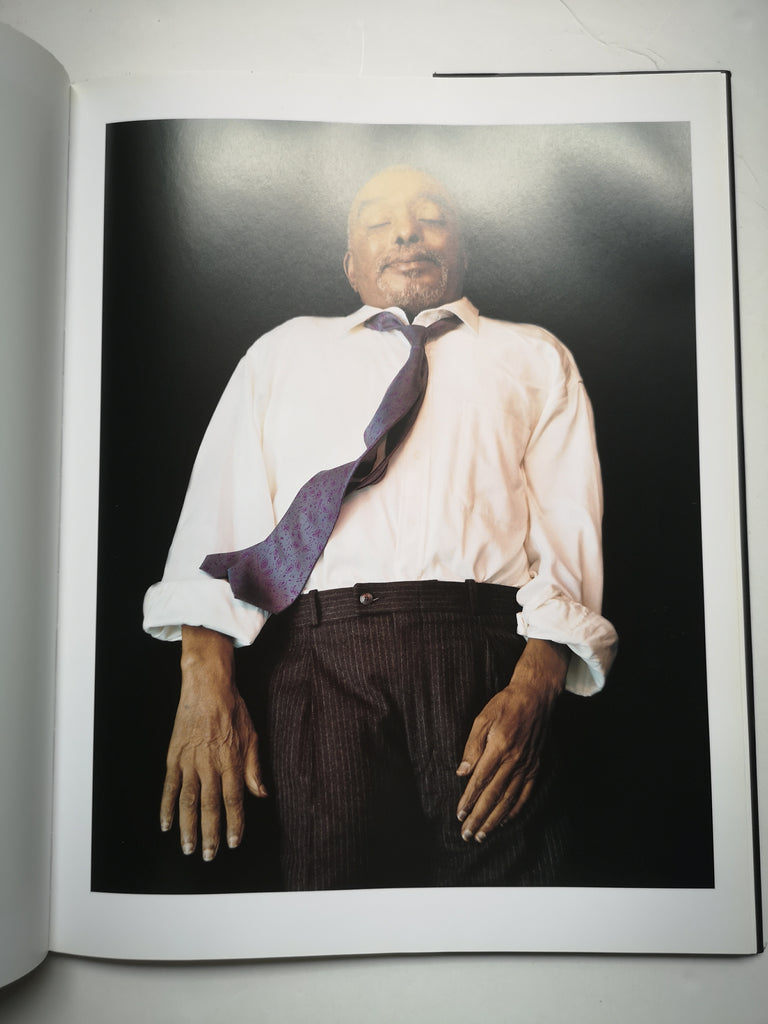

People here are dressed up for the journey to paradise. The women wore these incredible hats and a number of them wore burial gowns which were satin, sequined, like prom gowns. In a number of cases, different women were in the same style dresses, but in different colors. Women sometimes wore the Eastern Star. Men often wore white suits. The men also wore hats; the men who were Masons wore fezzes. Jewelry was common; people would be buried in all their jewelry, like the Egyptians. Often, people would be prepared by the funeral director, the service would be held in Harlem, and then the dead would be flown back to the South, usually to one of the Carolinas.

I tried to learn as many stories as I could about the various people who died. Here are some of my notes:

“died of AIDS, 60 lbs.”

“married for the first time in 2002”

“great-grandmother”

“food on sleeve—apparently he was known for spilling”

“of an elegant church lady: loved to gamble”

“school teacher”

“3 or 4 buses came from prison for her, because her whole family was in jail”

“splendidly dressed woman—had been in a coma for a long time, and her kids were fighting and fighting over her money. She woke up, called her lawyer, disinherited all the kids, and died the next day.”

“woman in amazing big white hat (played the numbers). also: hair had to have a rinse before she was buried”

“woman would always say, before she died, that when she died, someone was going to have to beat her wig the night before she was buried, meaning to sleep in it. As a very little girl, the daughter of a sharecropper, didn’t have any shoes until she was six—church ladies bought her a pair of shoes so that she could be in the choir, because she had a wonderful singing voice—shoes were too small, but she was afraid to say anything. She had to walk to church, she finally got there, collapsed in tears from the pain, and they all said ‘Hallelujah! She’s seen the light.’ Had her first child at 13.”

THE TRAVELERS, In Memorium, Naarden, The Netherlands

How do you think your race influenced the way you took these pictures?

I was always an outsider, for so many different reasons. I’m white, born and raised in the North, not a Christian or a believer in any god. I didn’t believe in the afterlife and I still don’t, but I wish I did. It’s a tremendously appealing belief. I wasn’t part of the Harlem community, not even slightly. As moved as I was, I was photographing something from a tradition that was foreign to me, and I think my outsider status helped me do this. The funeral director and I had many conversations about preserving history. He seemed to find it surprising that someone from outside the community would want to preserve this tradition.

I think that race was part of what drew me in. These people, many of whom were from the South, were from such a different background from mine; their stories were profound to me. Many of them must have experienced a vicious racism that I had only read about. I’m a white American and I know how shameful that history is, and how much we still don’t address it. Of course, this was a visual project, not an intellectual one, and if there was a funeral practice in Sicily or Japan that had this visual tradition, I might have gone there. But I wonder if I would have been as moved if it were in a foreign country. When I saw, say, that someone had been born on a plantation in the South in the ‘20s, I could imagine how far that person had traveled, the incredible distance. One man I photographed, for instance, was buried with an American flag. That’s common for a veteran, but when I saw the dates, I knew that he must have been in the segregated army. That’s shocking to me. But he and his family wanted to bury him with the flag. Only with the dead do you know the story from the beginning to the end.

During this year, you were always working between night and day, and with people who, in a way, really hadn’t quite crossed over to the other side yet. How did that affect you?

I hesitate to say this for fear of sounding too girlish, but during the year that I was working on THE TRAVELERS I felt that, though I was always outside at the glass looking in, I was looking at a wonderful world. It was full of things I don’t have: a big family, faith, traditions. Though there was the pain of not being able to share in it, I got to go into that world regularly.

But after I was done working in Harlem, it was like I was haunted. During the year of the project, I was almost unaware that what I was immersed in was about death. But afterwards, it was all about death. It was about everything about death that isn’t beautiful. It was about decay, loss, and people being completely gone. I had nightmares. My creative project was over, but also this family, this community, though I was never a part of it. I was so aware of my outsider status, that I’d never be a part of the world I was photographing and never experience it again.

I see this as part of a trilogy: THE SLEEPERS, THE TRAVELERS, and THE NARCISSISTS. But I’d never want to photograph the dead again, because after it ended it became not about beauty and community and history, but only about death. I thought about doing more pictures, but I couldn’t bring myself to do them. In fact, every single time after photographing someone, I thought, I can’t go back, I can’t do this. My two fears were that I’d never get to do another one and that I’d have to do another one.

How do these photographs fit into the tradition of memorial photography?

Actually, I didn’t think of what I did in Harlem as memorial photography at all. I was doing portraits of a community after death, a series of portraits. These portraits aren’t about death, but about people’s lives. I’m interested in what makes up the essence of us as human beings and what the person outside sees. We have strong reactions to the people, not to the fact that they’re dead. In a way it’s always a portrait of the viewer: a white person will see something different than an African American person, a religious person will see something different than a non-religious person, and so on. They’re not unlike eulogies: these photos are a visual version of what the living—the families, the funeral director, friends, I—want to remember, the stories we all want to tell about the dead.