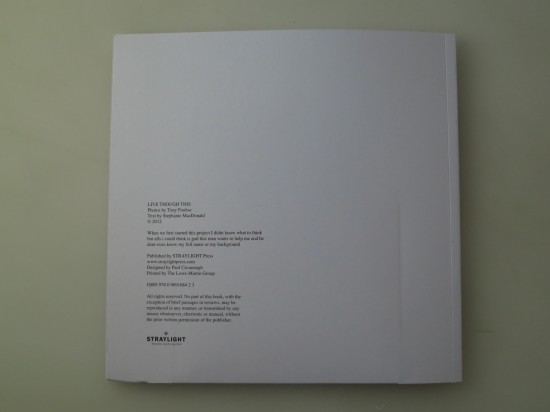

Tony Fouhse Book ‘Live Through This’ STRAYLIGHT Press 2012

Photo Book: ‘Live Through This’

Photographs by Tony Fouhse

Straylight Press, 2012. 86 pp., color illustrations throughout, 9x9″. Mint Conditon

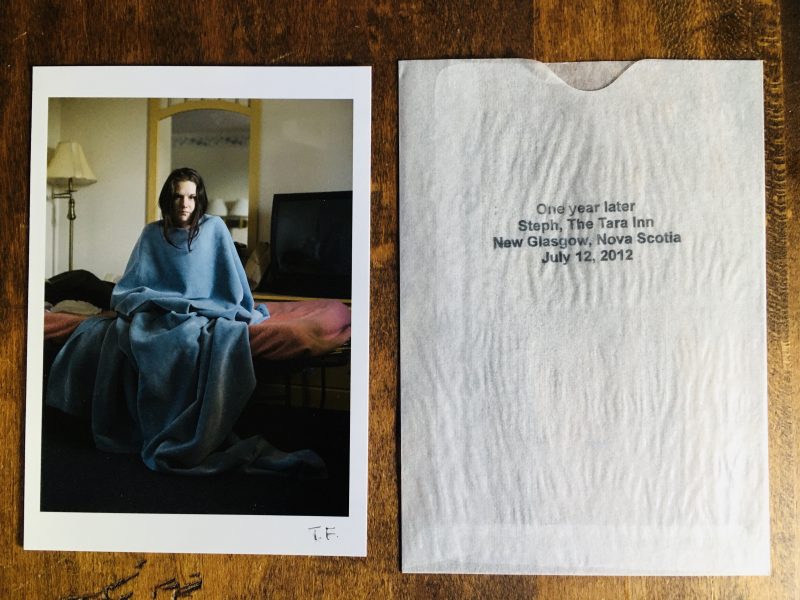

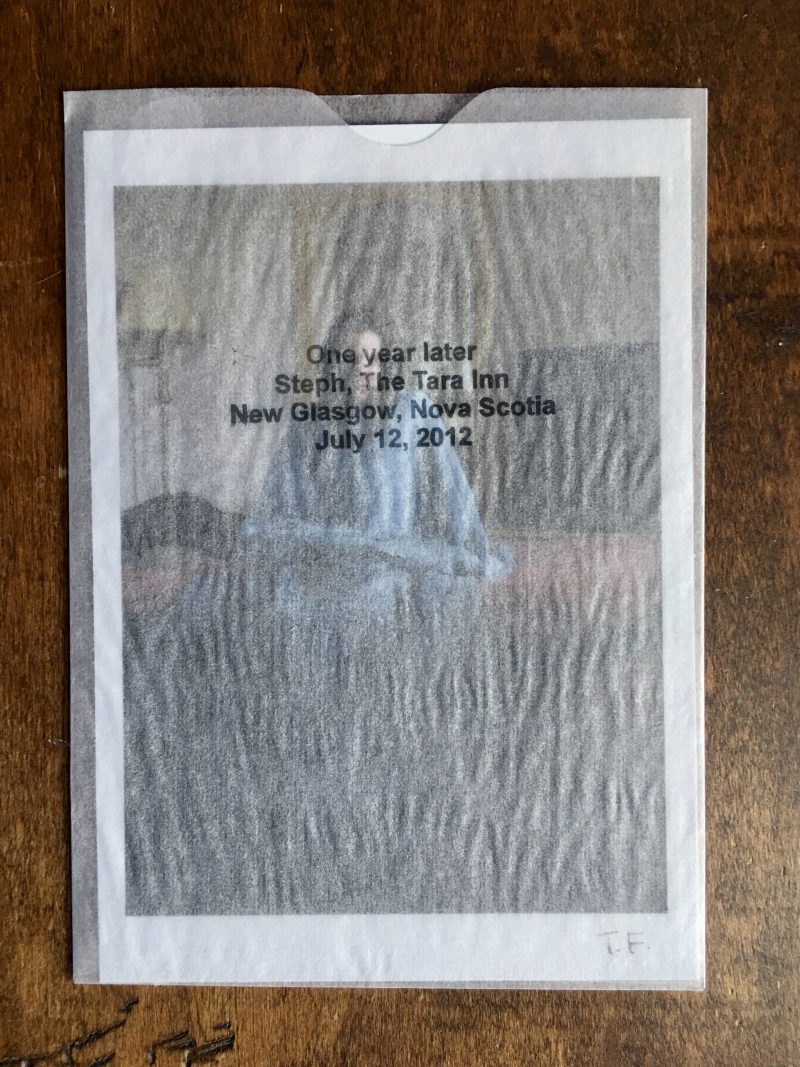

$125 includes small limited edition signed (initials) photograph portait of Stephanie.

Inscribed to me by Tony: ‘Thanks Guy for the support all those years, Tony’.

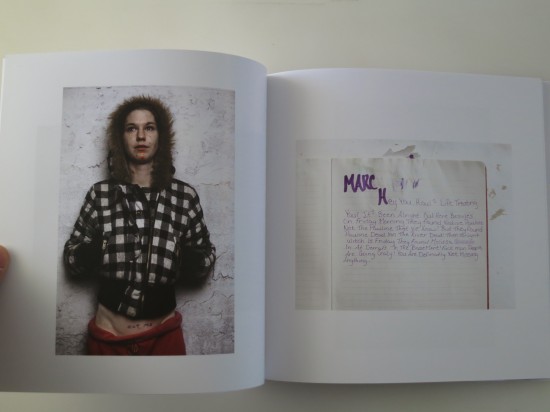

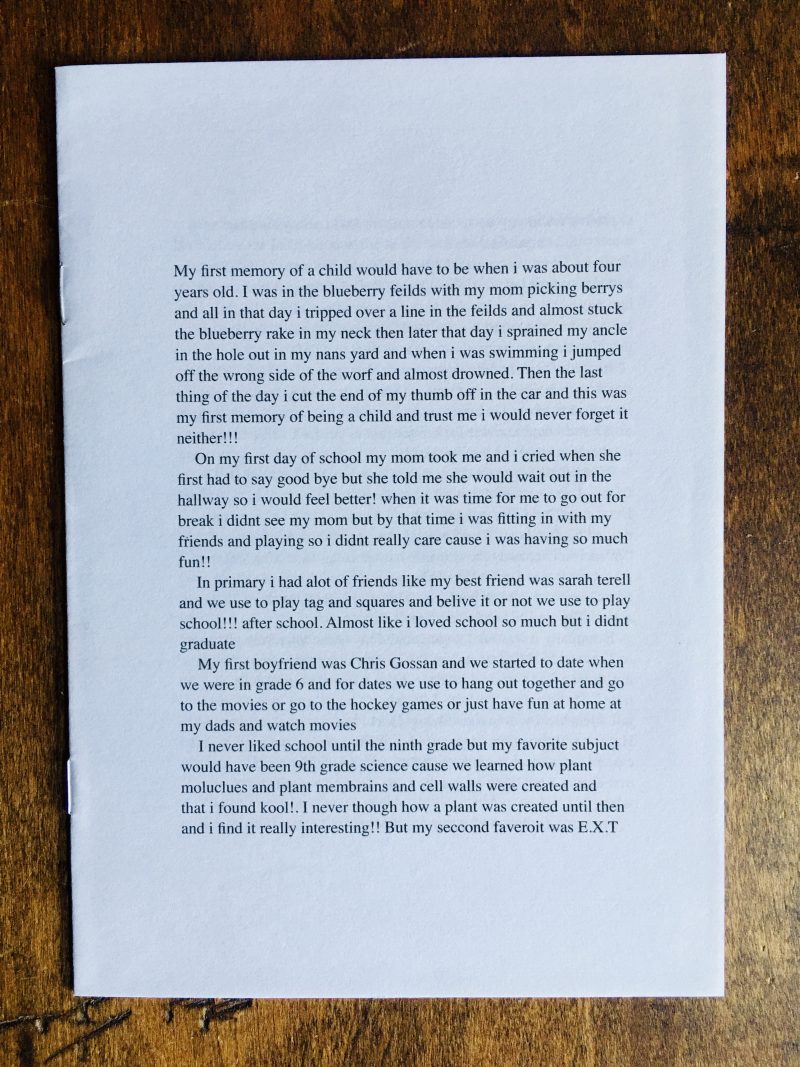

Include journal type text by Stephanie.

Softcover, 9×9 inches, 86 pages plus a removeable 8 page booklet that tells the story in Stephanie’s own words, from her point of view. Printed on a 4 color press, LIVE THROUGH THIS is limited to an edition of 750 copies

REVIEW:

This Week In Photography Books – Tony Fouhse

“Live Through This”, published by STRAYLIGHT Press, is packaged smartly. I faced a plastic sleeve, sealed with a carefully placed sticker. Open it up, and there is a cardboard cover, secured with a single rubber band. There is no artist name, or any info beyond the title. I was intrigued. The first blank page features only the pencil signature by the artist, Tony Fouhse. Turn again, and you get a small story about Stephanie, and how she should have died, to make what follows a better story. What?

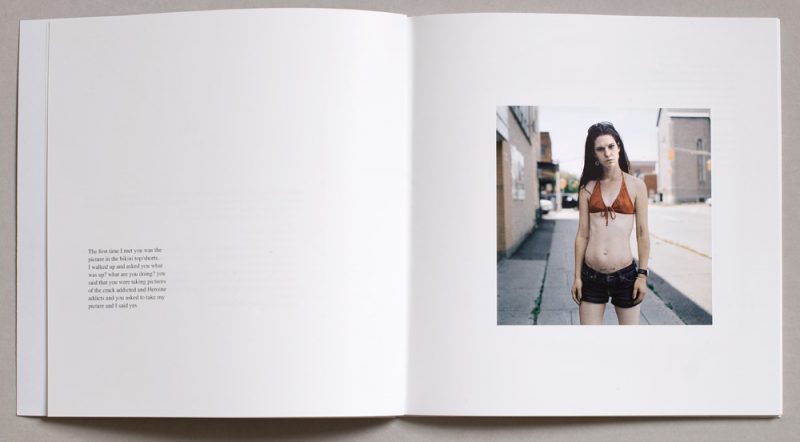

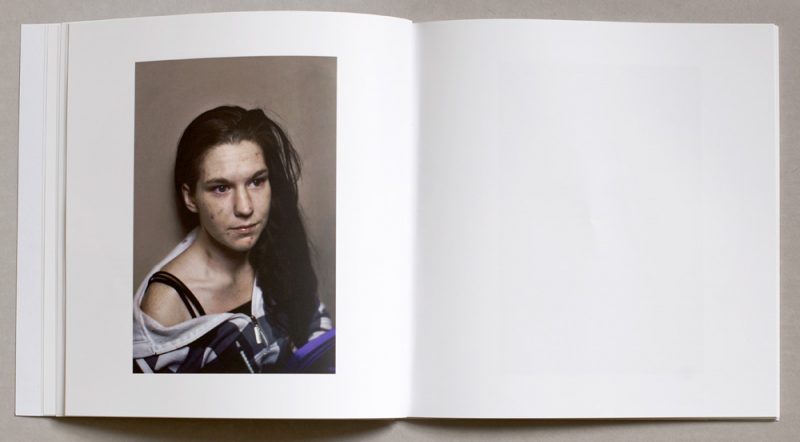

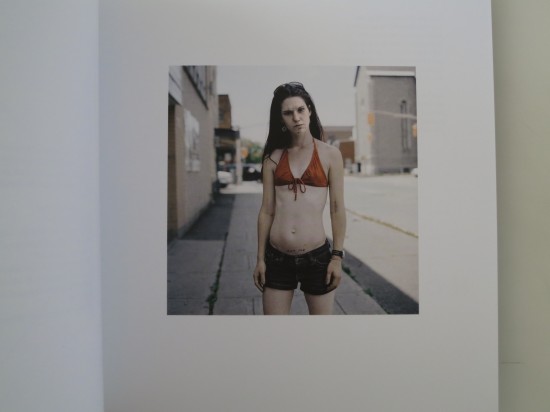

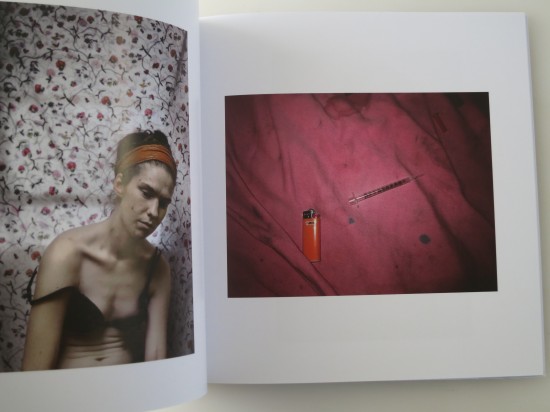

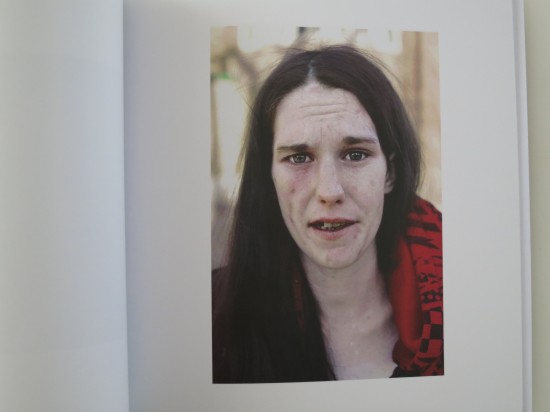

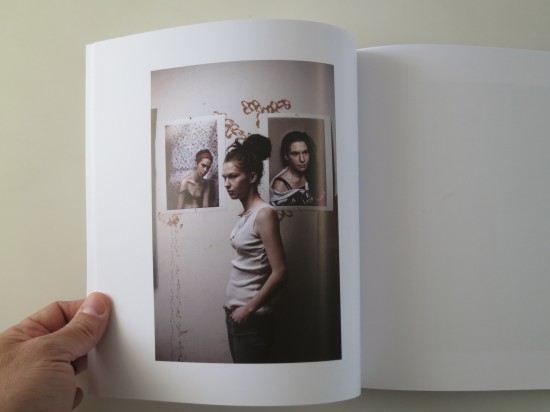

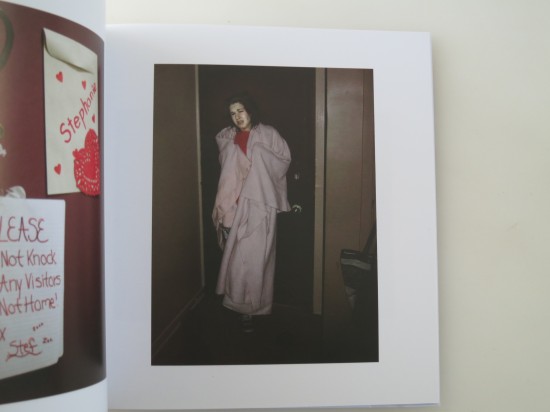

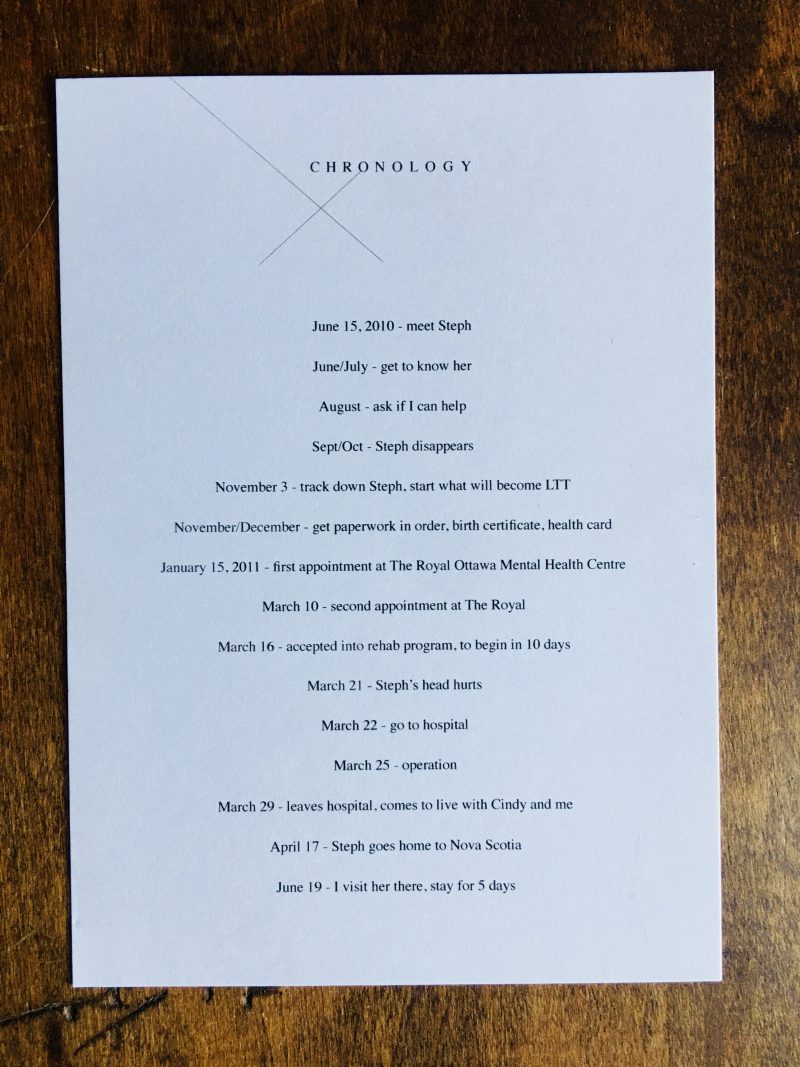

I’ll cut to the chase, and give you the crux of the narrative, as you don’t actually have the ability to slowly parse it out, page by page. (Unless you buy the book, which I would recommend.) Apparently, Mr. Fouhse was photographing heroin and crack junkies in Ottawa, and asked the young Stephanie MacDonald if he could take her picture. It’s the first portrait in the book, and she has a stunned-but-vacant look in her eye, a pock-marked face, and a staggering Eat Me tattoo just above her lady parts.

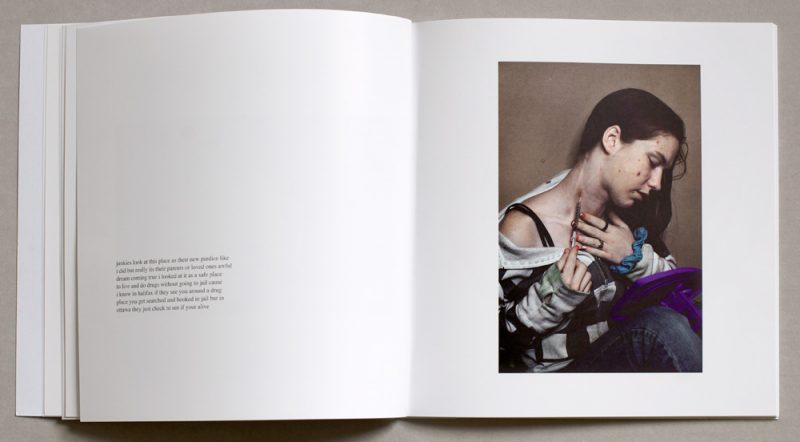

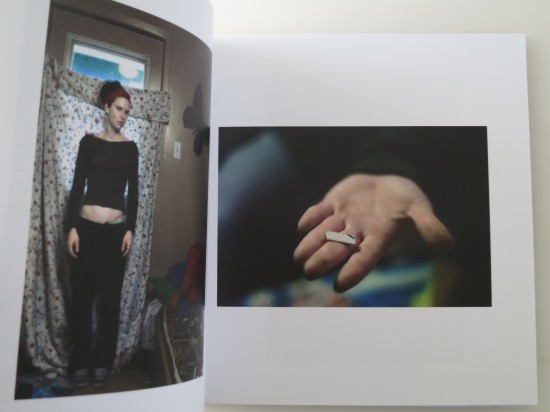

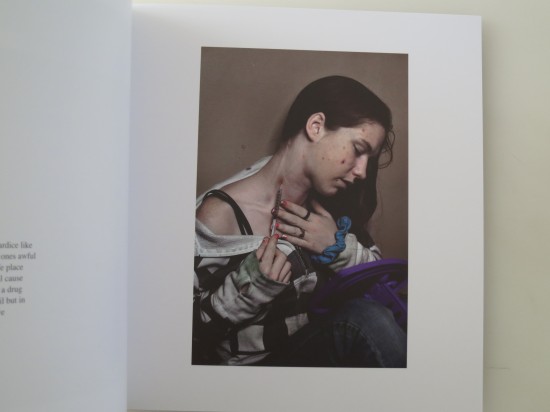

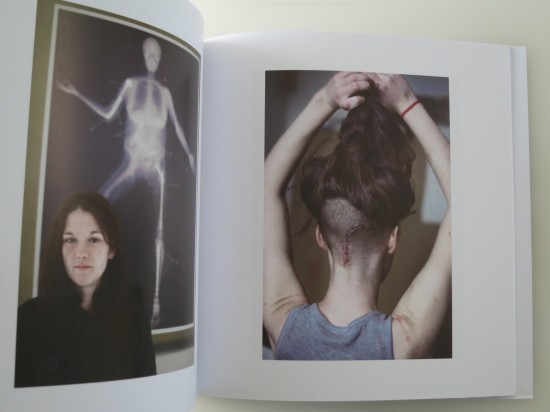

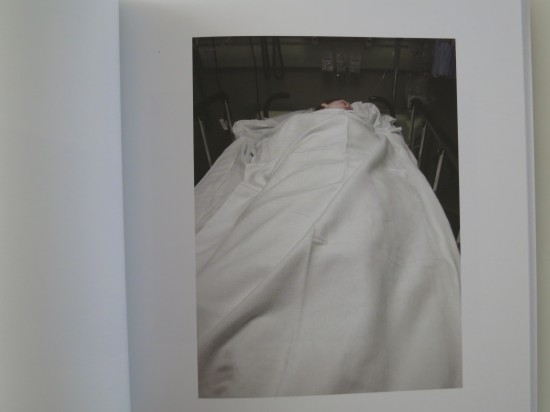

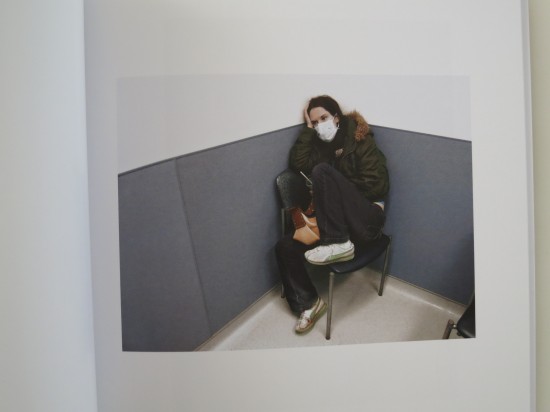

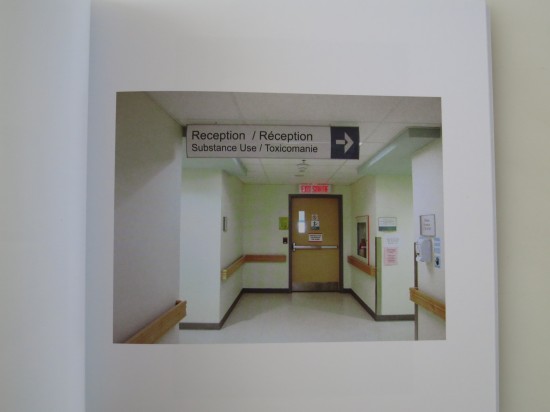

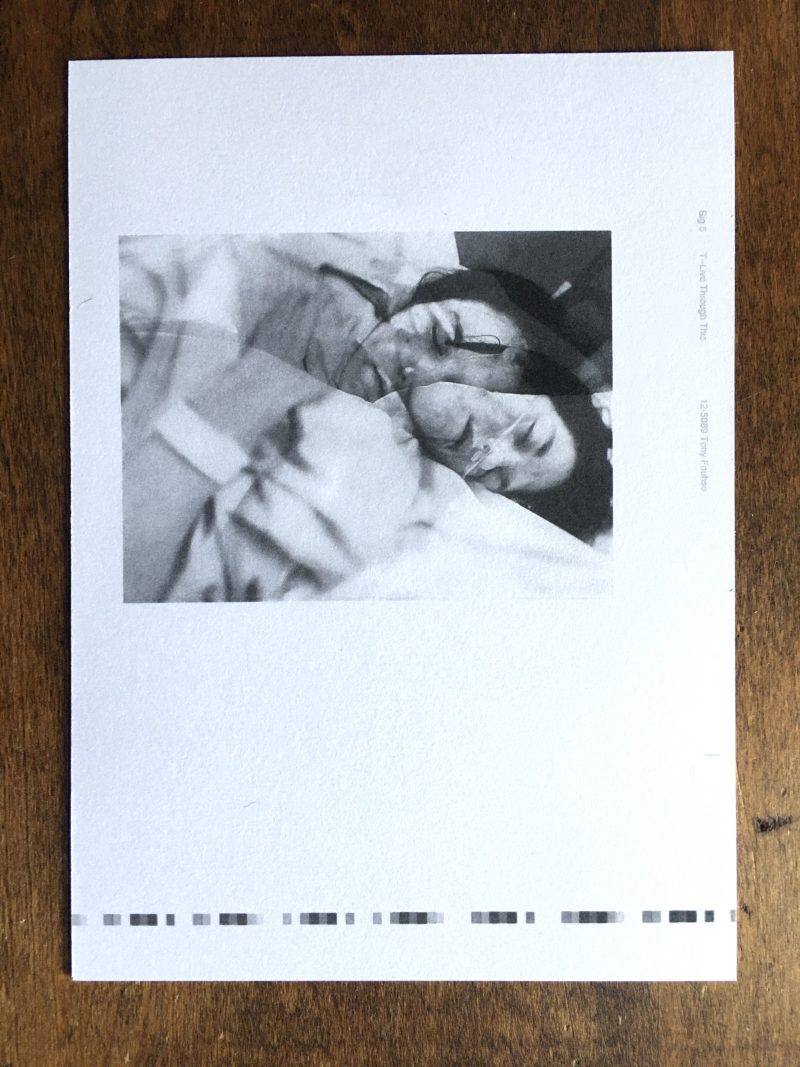

Thus began a relationship in which the artist offered to help Ms. MacDonald get clean. He intervened in her life, setting up a rehab stint, and stood by her when she had brain surgery, due to a dirty needle. The pictures throughout the book are accompanied by Stephanie’s own diaristic text, replete with bad spelling. (Who am I to criticize? I have typos almost every week.)

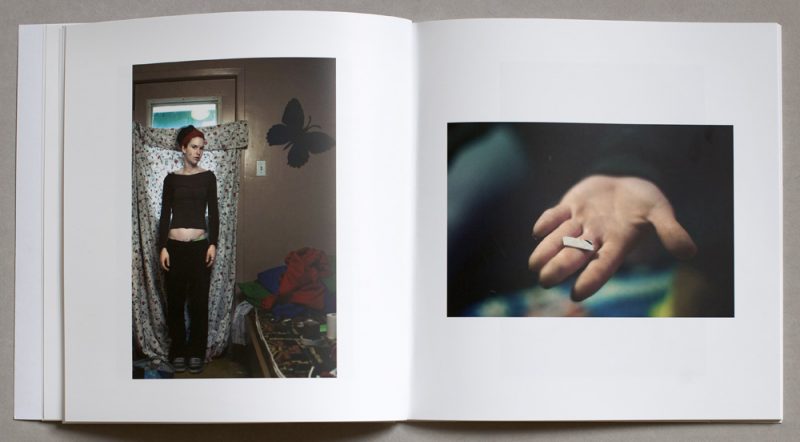

The pictures are certainly difficult to look at, but unlike those Meth-head billboards they have up some places, (I mean you, Colorado,) these images are not just meant to scare. They’re intimate and caring, while also representing a vision of reality that we don’t want to see, but should. Powerful stuff.

While I’m pretty sure Hollywood has not yet relocated to Canada, despite Vancouver’s sterling reputation for filmmaking, this book does have a happy ending. Stephanie cleans up, and even spent some time living with Mr. Fouhse and his wife. There is a cool little insert in the back that includes Stephanie’s entire narrative, the results of a drug test properly passed, and a signed portrait of her, post-addiction, with clear skin.

Drugs are a problem that will not go away. Despite being illegal, outlawed, the demand never dies. At present, the people reaping the rewards are often armed thugs, gangs of killers. So people push for legalization, which will bring tax benefits, and shift the profits elsewhere. Who will make the money instead? I’m not sure that’s been addressed.

But like David Simon demonstrated in his provocative “Hamsterdam” scenario in “The Wire,” even legalization will not tie a pretty pink bow on this intractable problem. People will succumb to addiction, do horrible things, and then die lonely deaths, either way. I had a cousin who went that way, despite seeming to have everything to live for. Demons often win in the end.

This book is a beautiful counterpoint to the misery, and a valuable lesson to us all. I know journalists are often in a position of having to tell the story, rather than intervene. That’s just the way it is. But here is a case where someone’s creative practice and generous heart made a difference in a young girl’s life. One less corpse to be discovered, and hauled off to the morgue.

Bottom Line: Difficult photographs of young woman’s climb out of addiction