Valparaiso, Chile / Disciples Project 2014

“Disciples” / “Discípulos”

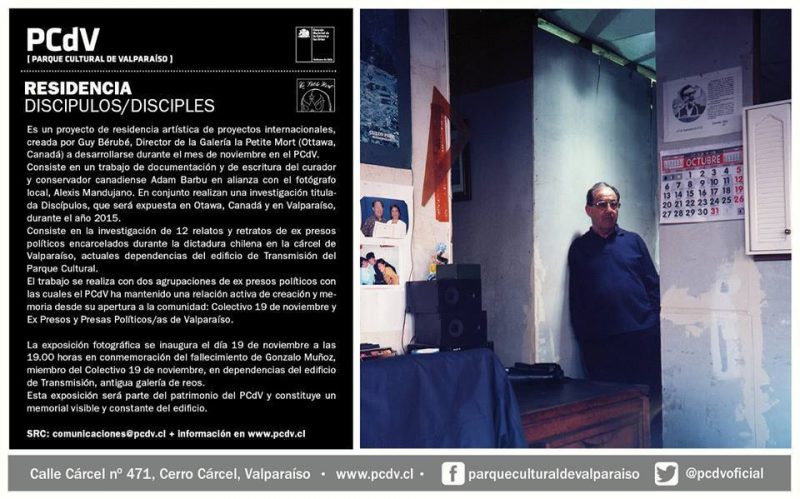

Vernissage: November 19, 2014, 19:00 Parques Cultural de Valparaiso, Chile.

This exhibit will also be featured by curator Guy Berube March 6-29, 2015, with the collaboration of the Embassy of Chile, Ottawa.

Guy Berube (Curator, Ottawa, Canada)

Adam Barbu (Writer and Co-Curator, Ottawa, Canada)

Alexis Mandujano (Photographer, Valparaíso, Chile)

Alonso Yañez (Productor General y Artista Visual, Parque Cultural de Valparaíso)

Justo Pastor Mellado (Director, Parque Cultural de Valparaíso)

The Project

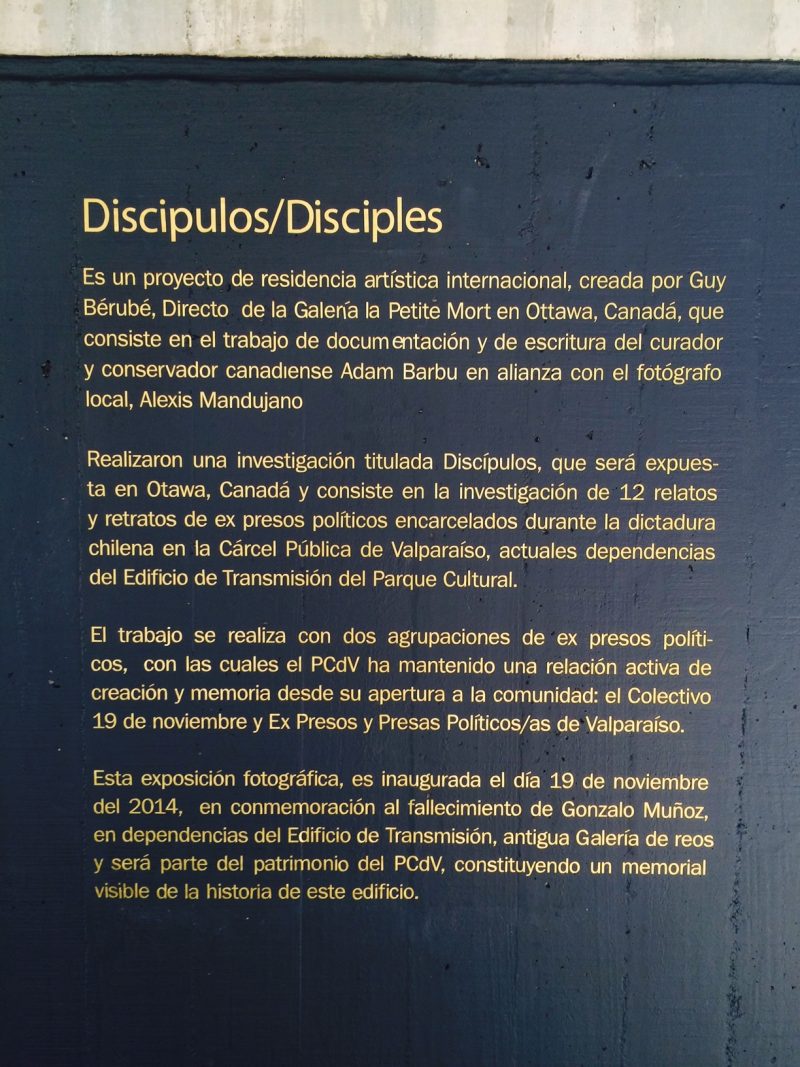

“Disciples” is an international curatorial project that will result in exhibitions at the Parque Cultural de Valparaíso (Valparaíso, Chile) and Canadian curator Guy Berube (Ottawa, Canada). Through a cross-cultural photography and writing component, the project works to extend the voices of twelve former political prisoners of the infamous ‘Cerro Carcel de Valparaiso’ in a contemporary context. In Valparaíso, the exhibition will be presented on the grounds of the existing remains of the prison. The exhibition will be travelling to Ottawa for March 2015. These individuals are neither ‘victims’, nor ‘survivors’, but messengers, as were the original Disciples. Their collective resilience through this dark, restless political history is a message of hope that transcends geographic boundaries.

Historical Context:

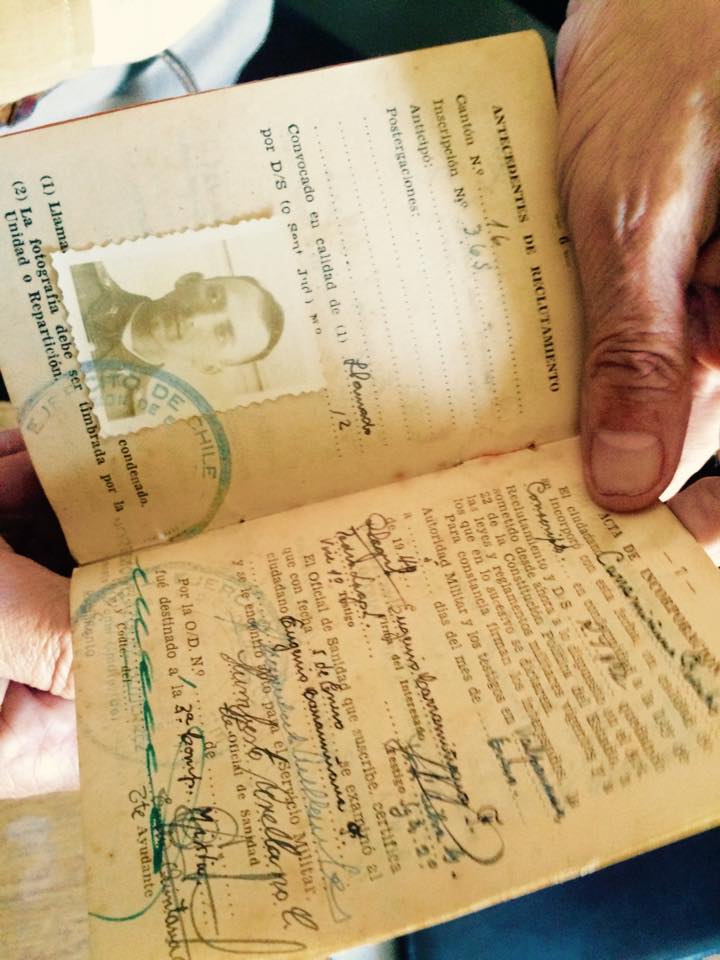

On November 19, 1985, a 19 year-old student protester named Gonzalo Muñoz was murdered in the infamous public prison of Valparaíso, Chile. His arrest and ultimately, his death, were a reflection of a highly divisive climate of injustice marked by the Pinochet dictatorship. Muñoz’s death is often viewed in terms of a paradigm shift of a renewed left wing resistance that would ultimately take the government out of power in 1988. That the project has been initiated on the 39th year is significant: It anticipates the commemorative moment by asking us to think of healing not in terms of resolution and resolve, but as a lived, private process of resilience carried out in the practice of day-to-day life. In this way, “Disciples” works in the memory of Gonzalo Muñoz, and the countless others who have been left voiceless at the hands of the regime.

Project Supervisor: Guy Berube, Curator (Ottawa, CA)

- Responsible for the coordination of the project in its totality, overseeing the programming, the production, as well as future developments of the residency.

- La Petite Mort Gallery is an unconventional local and international contemporary art gallery space located in Ottawa (CA), that produces a wide range of collaborative exhibitions and programs.

Writer/Co-Curator: Adam Barbu (Ottawa, CA)

- Education: Honors BA in Art History at the University of Ottawa. Currently pursuing an MA in Art History

- Independent writer and curator; exhibitions include Breaking Point (2013), Shoot Me, Please (2014), Sanctum (2014), Disciples (2014), Bad Timing (2015).

Project Photographer: Alexis Mandujano (Valparaiso, CL)

- Education:

- 2013: Viewing of portfolio with Pedro Meyer;

- 2011: Degree in documentary filmmaking at Escuela de Cine de Chile

- 2011: World Press Photo workshop dictated by photographer Jodi Bieber;

- 2010; Artist Residency in photography by the photographer Nelsón Garrido

- 2009, Studied photography at Instituto Profesional de arte y comunicación Arcos.

- Portfolio: http://alexismandujano.com/

“The Poet’s Obligation” by Pablo Neruda

To whoever is not listening to the sea

this Friday morning, to whoever is cooped up

in house or office, factory or woman

or street or mine or dry prison cell,

to him I come, and without speaking or looking

I arrive and open the door of his prison,

and a vibration starts up, vague and insistent,

a long rumble of thunder adds itself

to the weight of the planet and the foam,

the groaning rivers of the ocean rise,

the star vibrates quickly in its corona

and the sea beats, dies, and goes on beating.

So, drawn on by my destiny,

I ceaselessly must listen to and keep

the sea’s lamenting in my consciousness,

I must feel the crash of the hard water

and gather it up in a perpetual cup

so that, wherever those in prison may be,

wherever they suffer the sentence of the autumn,

I may be present with an errant wave,

I may move in and out of windows,

and hearing me, eyes may lift themselves,

asking “How can I reach the sea?”

And I will pass to them, saying nothing,

the starry echoes of the wave,

a breaking up of foam and quicksand,

a rustling of salt withdrawing itself,

the grey cry of seabirds on the coast.

So, through me, freedom and the sea

will call in answer to the shrouded heart.

Curatorial Essay

“Disciples”, Valparaiso 2014

States of Translation by Adam Barbu

Pablo Neruda’s “The Poet’s Obligation” is an important and intriguing piece of writing for the curious reason that it refuses to say enough. Neruda traces a space of ambiguous distance, unresolved desire and a present, yet precarious belief by questioning the ability of the writer to effect changes in his world. He writes:

yo circule a través de las ventanas

y al oírme levante la Mirada

diciendo: cómo me acercaré al océano?

Y yo transmitiré de la ola,

un quebranto de espuma y arenales,

un susurro de sal que se retira,

el grito gris del ave de la costa.

With this poem, we access the image of a poet who is held between three worlds – the surrounding landscape, the space of the text, and the realm of memory in which he attempts to know the people that he cannot know.

“Y yo transmitiré de la ola…” This line is provoking, and easily misread. Neruda does not advocate for the invisibly of the narrator’s voice, nor does he seek out this narrator’s ‘honesty’. Rather, that this narrator must attempt to seek out a balance between the self and other. The writer has a responsibility to extend the dignity of the faceless, the invisible, and the disguised by extending his voice outward. This is a relationship I too must negotiate with the “Disciples” project. Understanding the essence of my ‘distance’ compared to Neruda’s ‘closeness’ to Valparaíso has allowed me to consider my obligation as a writer here and now.

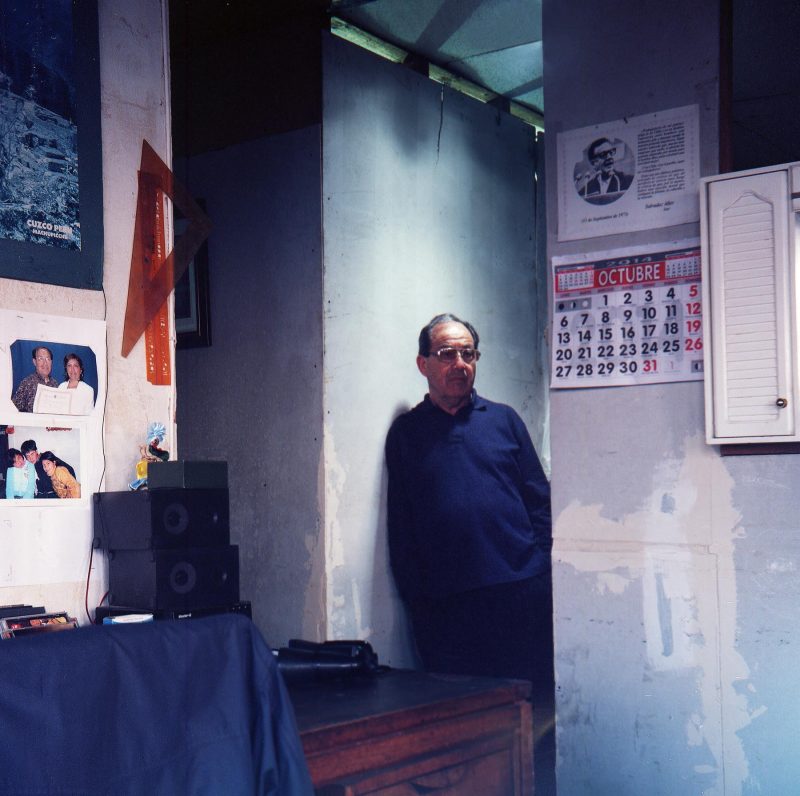

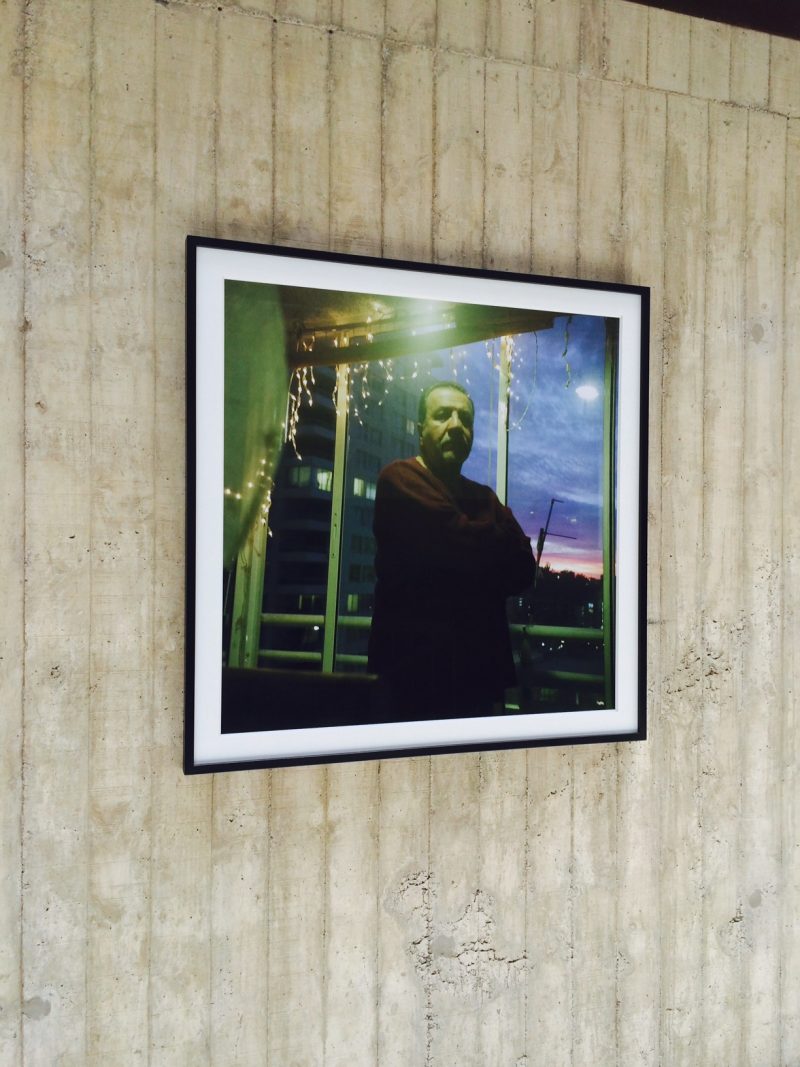

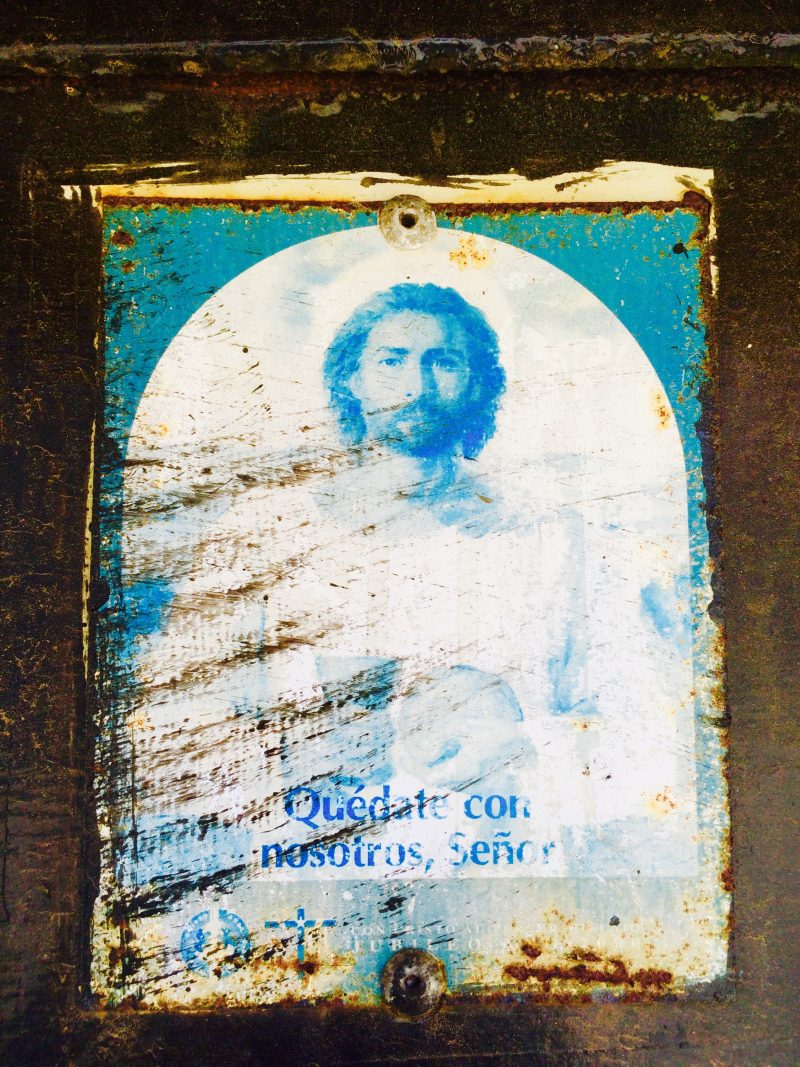

The title “Disciples” is used with dignity. This project was conceived as a way to raise the status of the messenger. In Valparaíso, “Disciples” works in dialogue with former political prisoners of the Pinochet regime who were held in the infamous ex Carcel de Valparaíso. This inaugural version of the project consists of twelve intimate portraits of former political prisoners shot by local photographer Alexis Mandujano. On November 19, 2014 the exhibition will be presented as a permanent installation in the existing remains of the ex Carcel itself. Today, the prison frames a space of restitution and renewal. And presented in this context, these individuals are neither ‘victims’, nor ‘survivors’, but messengers – they are disciples. At its heart, the “Disciples” project was created to grow and expand from this number twelve – to reach other spaces, to highlight other histories, and to trace broader networks of personal and political resilience.

Thus, just as I must translate Neruda’s poem, the words of the disciples, my correspondences between Chilean artists and administrators, and this text itself in order to understand and to be understood, I must also learn to translate the precariousness of my distance to the city. I must finally translate this decision begin writing so that it is not indifferent. From this perspective, we learn that language is in a constant state of transition; that our words can never be properly understood; and that our lives and our histories are together caught in states of translation. We learn that this disconnection of location, generation and language is in not a closure, but an opening for new kinds of questions to be asked, and for new relationships to emerge.

In its essence, The “Disciples” project looks beyond the systematic terms and timelines of the prison sentencing process. What we have learned is that when an individual is released from prison, we cannot easily say that the sentence is resolved. We must look to the hardships, the resistances and the transitions this individual must negotiate after the terms have been lifted. This tension is heightened when we consider the lasting legacies of explicitly politically motivated sentencing. These are physical and symbolic wounds and violences that, in abstract ways, continue to weave the cultural fabric. This is an aspect of experience is so easily forgotten, and perhaps further, so often hidden from view. To tug at this ambiguous space between the record, release and a life lived, is to ask a very basic question of our expectation of the term ‘freedom’ itself. The “Disiciples” project attempts to understand collective cultural healing through the power of visibility. The photographs also situate these personal and collective resistances in an important historical period, nearly 40 years after the coup, where two generations have grown up after the regime.

One will note that each of the portraits references the unraveling of time into the present -windows, passages, restrictions and perhaps most importantly, the transience of light. Each of the disciples carries a sobered, dignified facial expression of reflection, wisdom and belief. It is important to emphasize that the disciples have been photographed in domestic and private settings. Mandujano frames a complex space of settings within settings, and through this lens, questions the ways in which physical space frames symbolic meaning. Here, the disciples’ presence is both site-specific to the intricacies of each room, and geographically transcendent in its humanistic reach.

There is no adequate way to properly express our gratitude to the disciples. For without their warmth, openness, and honest this project would not exist. They have allowed us to look inside these difficult histories in a safe, honest space of friendship. I continually reflect on their courageous decision to share this moment with us – it is this simple gesture in and of itself acts as a teaching device for us all.

Thus, the “Disciples” is not about documenting ‘otherness’, nor is it politically driven. Rather, it is about the power of speech itself, and thus, marks an attempt to trace connections where they would otherwise not exist. There is no more direct or poignant way to address this than through an exchange between the image and written word itself. In this way, we are working to trace the complexities of communicating histories between insiders and outsiders, a distance that is held both within and between cultures, languages and generations. The hope is not only to better understand the lives and histories of our immediate subjects –the disciples – but also, to better recognize ourselves as bystanders.

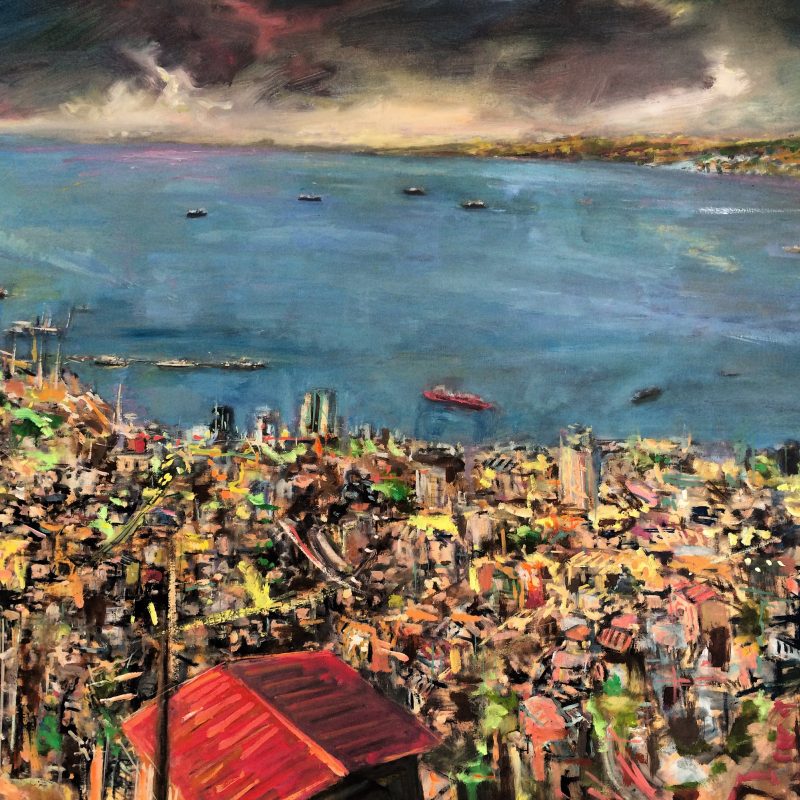

In the short text A Valparaíso (2013), Françoise Nuñez writes: “Je voulais, avec le souvenir lointain que j’en avais, découvrir cette ville comme une première fois.” I sit writing this text on my first night in Valparaiso. A year ago today, I could have never predicted the development of this project and the network of engagement it would produce. I projected a future memory – an imperfect nostalgia – for a city I had not yet walked and seen. Still, Valparaíso is a recurring abstract I have had, and continue to have, but alas, a dream I cannot reproduce. The voices of the disciples are the anchors of this dream.

Longing is a powerful force – with “Disciples” it forms on the belief that through the language of art we can reach across geographic distances, the belief that we can hear the words of strangers, and the belief that history is not a closure, but an opening. Valparaiso is the gesture of a promise to a future I do not know. In this fragile present moment, one is not simply the sum of his past experiences. We are the distance that the body assigns to history and to the ocean. And it remains that this distance is the becoming of a future voice, or a future image – one that we may hear of see, but cannot yet grasp. The stories of the disciples embody this future moment. In truth, the effort works on the intersection of fifteen offerings– the images of the twelve former prisoners, the voice of the writer, the eye of the photographer, and finally, the ardent spirit of Valparaíso itself.

PRESS: http://www.architectural-review.com/open-city-ex-crcel-parque-cultural-by-hlps-in-valparaso-chile/8637480.article

An excitingly muscular adaptation of an old prison – where Pinochet’s victims were once tortured – gives the Chilean port of Valparaiso a new cultural centre

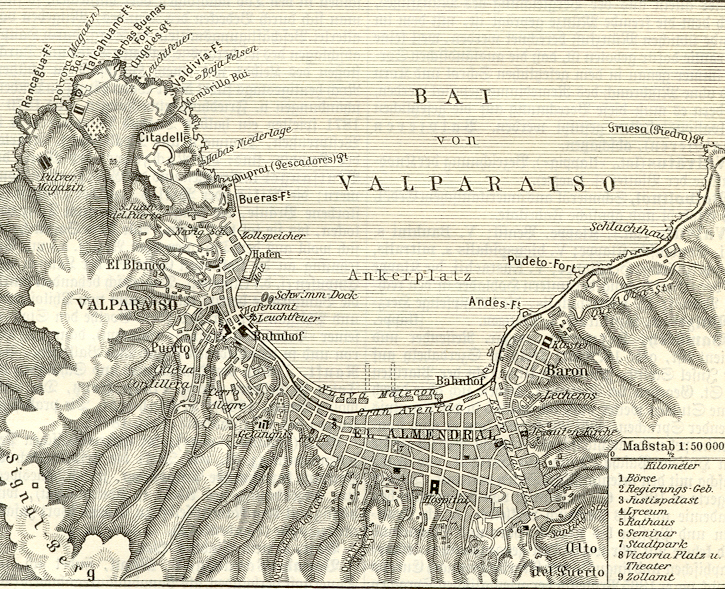

A labyrinth of narrow streets courses down a steep escarpment to a narrow strip of coastline and the port of Valparaíso. Beginning with the Spanish settlement and especially in the 19th century, it flourished as an essential stop for ships routed around the Horn. In the 1910s, it was devastated by an earthquake and bypassed by the Panama Canal. Today it’s a colourful relic, its trading activity much diminished, its mansions and vintage funiculars quietly decaying.

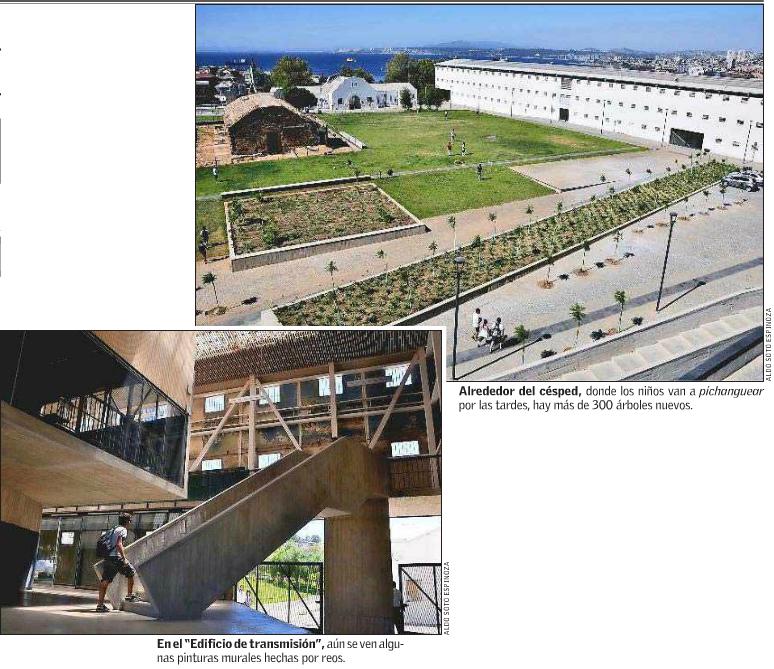

A gargantuan parliament building marks Pinochet’s clumsy effort to reinvigorate downtown. A far better symbol of the city’s continued vitality is the new Ex Cárcel Parque Cultural, located halfway up the slope, which combines open space for recreation and public events with a performance venue and studios for creative activities.

The Spanish levelled the five-acre site to build a fort, and this was later converted into a jail where political prisoners were confined and tortured during the years of dictatorship. It had stood empty for 15 years when the city’s department of public works sought proposals for its reuse, stipulating that the exterior of the cell block be preserved, along with a barrel-vaulted brick armoury that is a protected colonial monument.

Four former classmates at the Valparaíso campus of the Pontifical Catholic University joined forces to enter the competition and they beat 120 established firms. It may have helped that Alejandro Aravena and Smiljan Radic − two of Chile’s top architects, who teach at the Santiago campus of PUC − were on the jury. Both embrace innovation and socially responsible projects − hallmarks of the Valparaíso school. Most likely the quartet won because, in contrast to other entrants, they maximised the amount of open space, by clearing encumbrances and limiting new construction to one corner of the site.

To realise their design − in two years at a cost of £10 million − Jonathan Holmes, Martin Labbé, Carolina Portugueis and Osvaldo Spichiger formed HLPS Arquitectos, and brought in Paulina Courard to supervise the landscaping. The challenge was to turn a place of dread into a friendly oasis − ‘a flowerpot in the Valparaíso hills’ as the architects call it − opening a once impenetrable site to the city. They’ve achieved this through varied landscaping and by concentrating the performance and service spaces in a single concrete block that doubles as a point of entry, with a ramp leading over the roof and out to the street further up the slope.

The windowless block was conceived as a floating beam with minimal points of support and cantilevered ends. It shades a portico and its roof terrace is a belvedere from which to survey the park and the sweep of the city cascading into the Pacific. Within is a large black-box theatre, a mediatheque, restaurant and library together with an upstairs dance studio; functional spaces that are intensively used.

The facade of this new structure complements the linear cell block that defines another edge of the park. As many as 1,600 prisoners were crammed into 200 tiny cells flanking a central walkway on three levels. This warren had to be gutted but not entirely erased. Inspired by Gordon Matta-Clark, the architects cut everything away until they were left with a roofless shell and a patchwork of colour, pin-ups and inscriptions on the inner walls, which provide a moving palimpsest of prisoners’ lives.

They inserted a steel frame to support a new skylit roof, and seven organically-shaped concrete studios for dancers, artists and musicians. Their curved forms complement the orthogonal frame, enhance interior acoustics, and provide additional seismic reinforcement for the outer shell. Two of the five ground-level studios have sunken floors to add height, and they are flanked by an open-sided concourse to the rear and a glass-fronted museum of local history on the park side. Two upper-level studios and community meeting rooms are accessed from a mezzanine gallery.

The layers of the building’s history can be still read in its latest incarnation. (Click to zoom)

A small colonial-style villa, formerly officers’ quarters and set at an angle to the jail, has been converted for use by administrative staff, and the armoury at the centre of the park has been reinforced with arched steel beams and a new concrete portal to serve as a second museum. A grid of jacaranda trees to one side of the armoury defines an area for passive recreation, and clusters of magnolia, ceibo and palms enrich the park. The largest area is turfed for soccer and popular gatherings.

As beginners, working fast on a tight budget, HLPS had limited options, but it’s remarkable to see how well they’ve succeeded in balancing the claims of past and present, passive and active, creative and recreational. The four buildings anchor the space, and the balancing act of the concrete block complements the white facade of the jail with its repetitive punched openings.

The artists’ studios offer privacy but open onto a public walkway, and the layered spaces of the concourse and steel mezzanine gallery are barred with natural light to convey a sense of mystery, even menace. These are tough buildings for a community that has more than its share of poverty and crime, but can aspire to a brighter future. And they open up vistas of a city that can rarely be seen as a whole.

It’s clear why the Spanish located their fort at this ideal vantage point for surveillance. From here you can appreciate the density and diversity of Valparaíso, from the Beaux-Arts and Art Deco monuments at the base, to the fanciful use of colour and fretted metal facades of the houses and tenements higher up.

‘As a fledgling firm, we share the belief of established firms that it’s better to be good than novel,’ says Carolina Portugueis. ‘We are very conservative.’ It’s a surprising admission from one so young but it puts her practice in the mainstream of Chilean architecture, which has long valued strength and sobriety over irrational exuberance. And it’s an apt stance in a country at the edge of a continent, constantly shaken by devastating earthquakes, and grappling with a host of social problems.