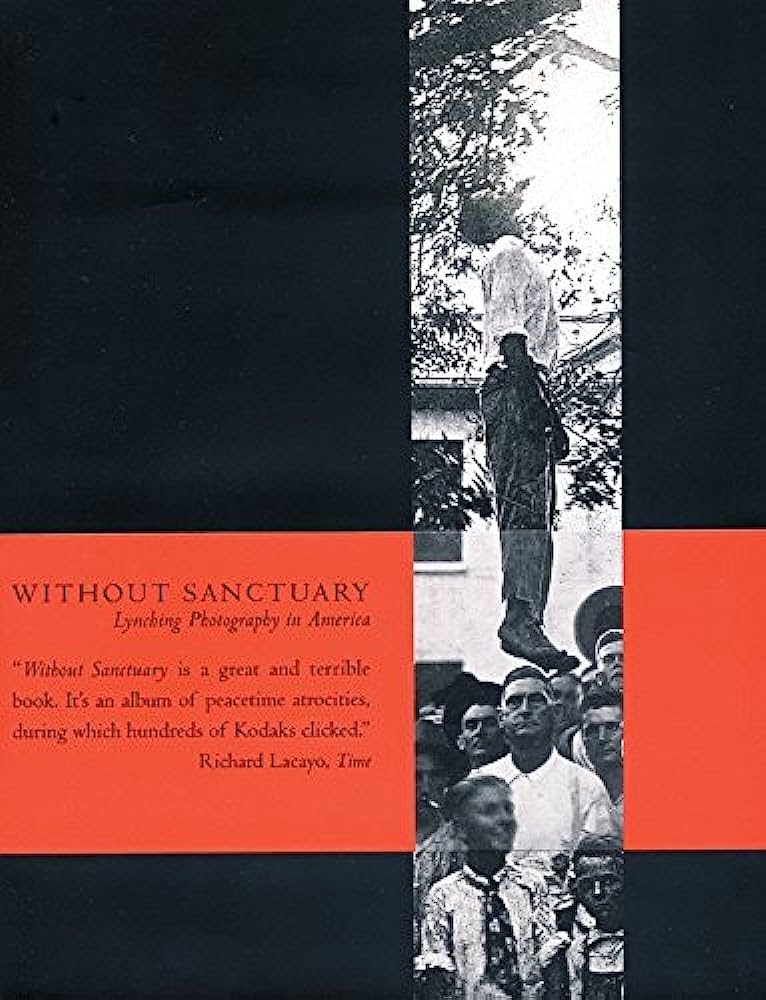

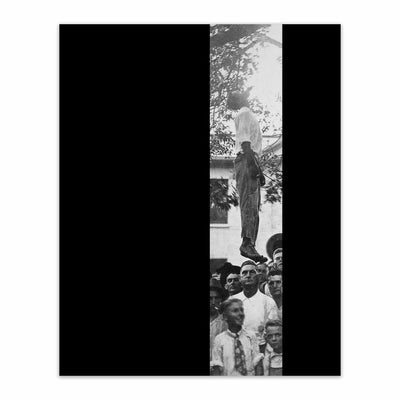

Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America

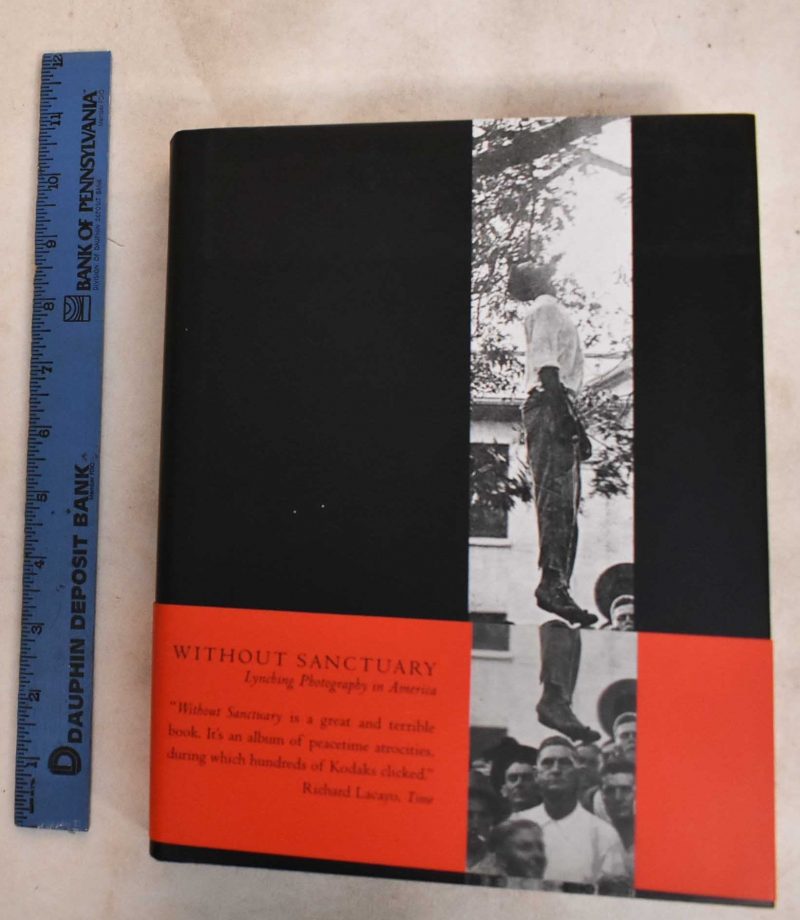

Santa Fe, NM: Twin Palms Publishers, 2000. Hardcover. Black cloth boards with black spine lettering, black dust jacket with bw illustration and white lettering, 1/4 red dust wrapping, 209 pp, profusely illustrated in bw and color.

- Publisher : Twin Palms Publishers; 10th edition (Feb. 1, 2000)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 209 pages

- Item weight : 1.22 kg

- Dimensions : 20.3 x 3 x 25.4 cm

Review

A book featuring lynching photographs from America brings home a reality we cannot ignore

Allowing us to view lynching from a distance, ‘Without Sanctuary’ makes us realise our own complicity.

“I have seen a man hanged. Now I wish I could see one burned.”

So said a nine-year-old child to his mother, on his way back from witnessing a public lynching in the late 1800s, once upon a time in America.

Tonight I write the saddest lines. A book review, thrice begun, thrice abandoned. Naive fool I, I had hoped that the last abandonment would be the final one, but that is not to be. I now tell the story of an old book, about old crimes, from another place – Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America.

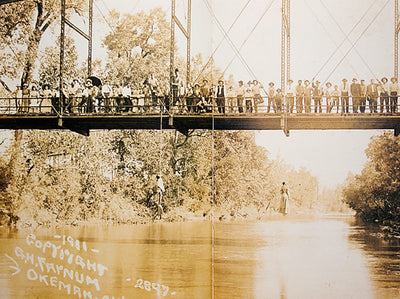

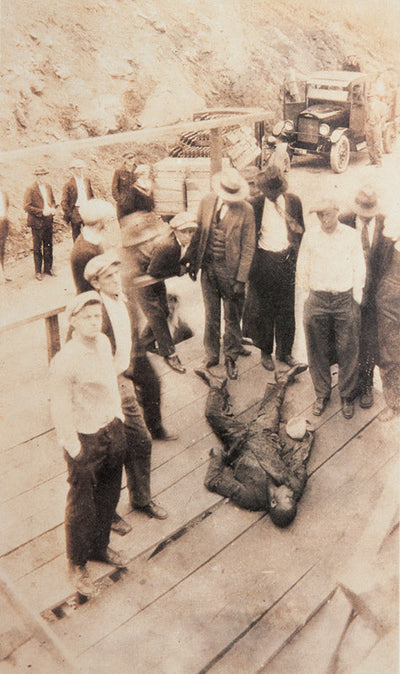

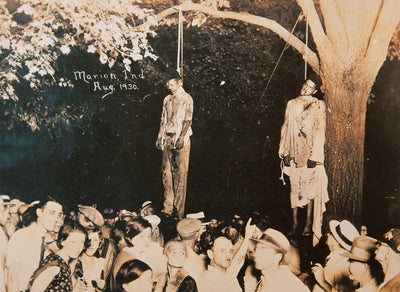

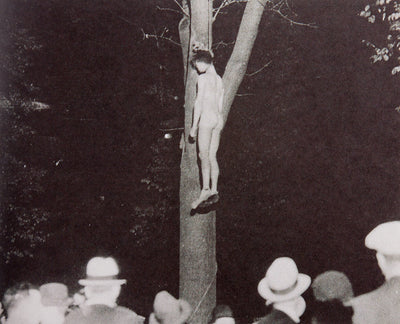

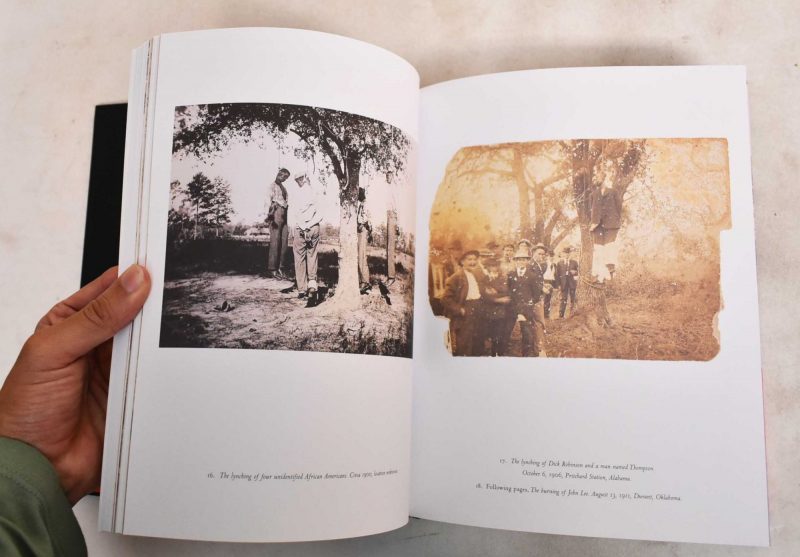

It is a new year. 2019. Four days in, I read the newspapers, and my mind is wrenched back to images from the book that I first saw over 14 years ago in North Carolina. Black-and-white photographs of black bodies lynched, hanging from trees, from bridges, damning their lynchers, but also their entire nation, confronting all who view them with silent accusation.

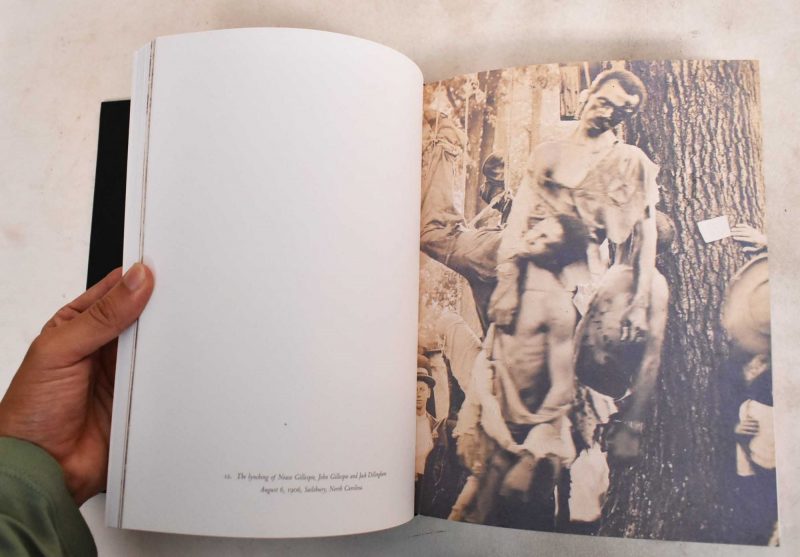

The image is horrifying: it haunts us. But these are not our spectres. This public murder, perpetrated so far away from us in space and time, is not our crime.

And yet it is. Lynching – murder with public sanction and political backing – pits the powerful against the powerless; pits a teeming mob against individual bodies, where regardless of guilt or innocence, those bodies stand not a chance. Because of this fundamental asymmetry, it is an eternal claim that the victims of mob violence – people murdered by the public without trial, without appeal, without mercy, and without sanctuary – make upon us, an eternal claim for justice. This is why this picture catches us, and will not easily let us go.

Why the photographs?

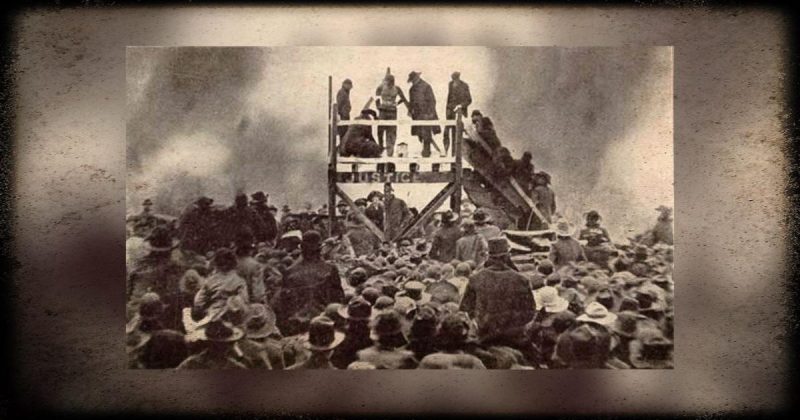

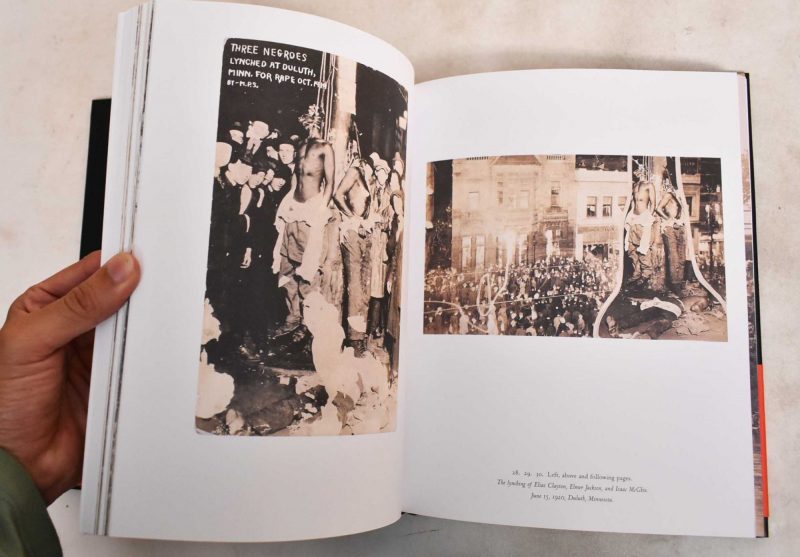

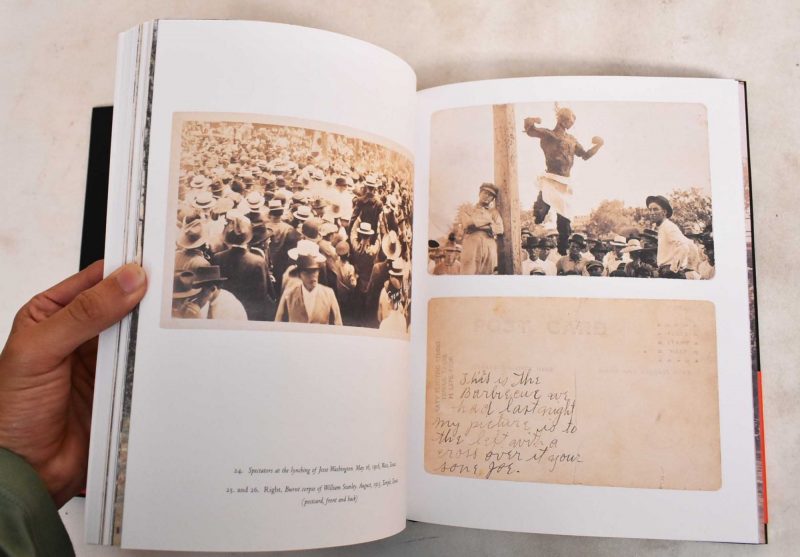

Look more closely at the photograph, if you can, and something more terrifying still emerges. See the crowd all decked out? The men and women in their Sunday best? The dark-haired lady in her printed dress? The man pointing up at the body in the tree?

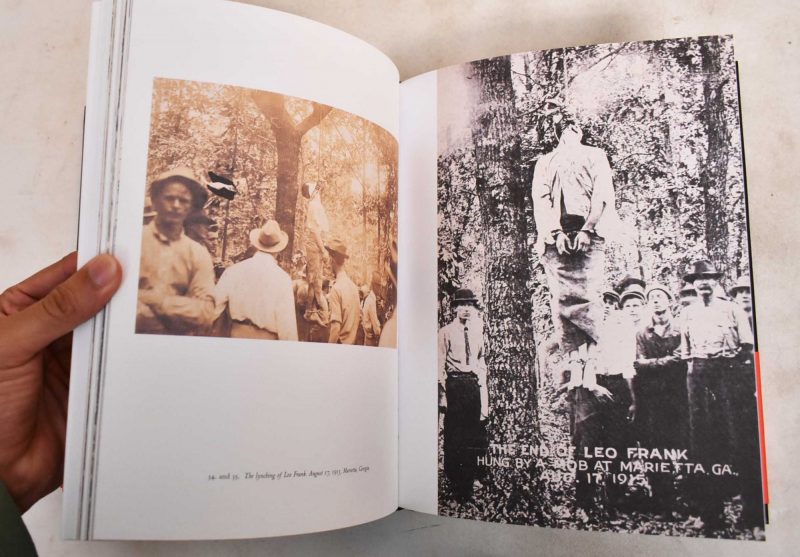

These are the crowds that would routinely come to view and participate in the lynchings of the time, creating an atmosphere that was cheerful, celebratory, festive. Between 1882 and 1968 an estimated 4,742 African Americans in the United States were murdered by lynch mobs.

Lynching was a way to keep blacks “in their place” through acts of public terror after the civil war and the ending of slavery. It was an extra-legal but socially-acceptable form of political violence adopted by a society on the churn, where fundamental social compacts – the basic orderings of society – were being overturned and reshaped.

In a climate where lynching was an acceptable expression of the hatred of a more-powerful community against a less-powerful one, viewing lynchings became another fun family activity, a festival of hate. A place to take your nine-year-old to see hangings and burnings and things further still.

At a moment when photography was just coming into its own, it was natural to want to document and preserve all that shared joy. To accompany the spirit of public lynchings then, people bought and sold and circulated picture-postcards of these lynchings, and sent them to family and friends accompanied by handwritten notes that said things like, “This is the barbecue we had last night.” WhatsApp messages of their time.

An undeniable history

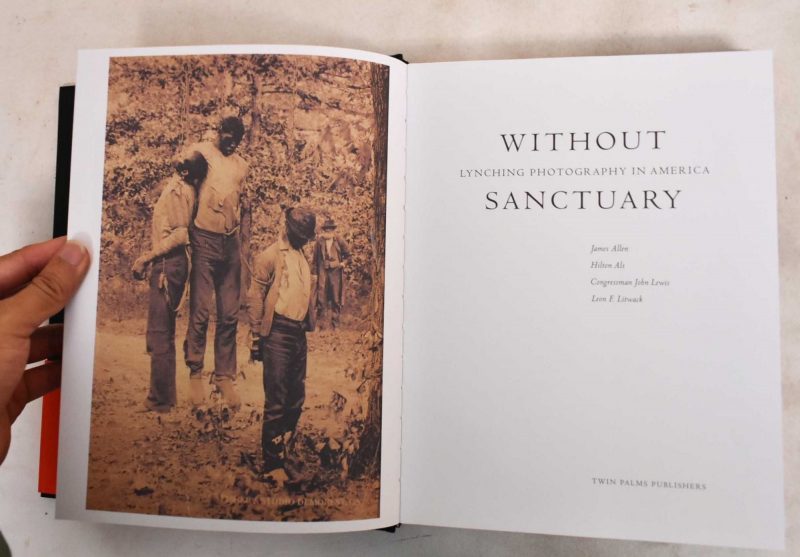

It is a collection of over 91 such postcards that forms the crux of Without Sanctuary, framed by moving and profound essays by collector James Allen, historian Leon F Litwack, Congressman and civil rights legend John Lewis, and New Yorker critic Hilton Als. Each of these essays tells a different story, offering differing perspectives. Als, in a searing and legitimate critique of the entire project itself – objectifying as it is of the bodies of lynched African-Americans – finds himself ultimately “unable to determine the usefulness of the project”.

I thought of Als’s essay for a long time before finishing this piece, before choosing to refer to the image that I have, before exposing these bodies to another set of eyes in another place far away. Ultimately I was guided by Congressman Lewis’s claim that “…many people today, despite the evidence, will not believe – don’t want to believe – that such atrocities happened in America not so very long ago. These photographs bear witness to…an American holocaust.”